“We made mistakes,” José Mourinho said after Manchester United’s 3-2 loss to Brighton & Hove Albion on Sunday. “And we were punished by the mistakes.”

After adroitly deflating a question about team chemistry and communication—“You must be fantastic at your job to have the ability to, from the stands, to speak about chemistry between players”—he repeated himself: “We made mistakes. We were punished by the mistakes. I cannot say more than that.”

As always, he’s right—if you ignore everything else. United can finish top four—if they don’t make any mistakes. United can make a deep run in the Champions League—if they don’t make any mistakes. But you, me, Paul Pogba, David de Gea, and José Mourinho—we all make mistakes.

Last year, United finished in second because they didn’t make many mistakes. They scored with a higher percentage of their shots on target (39) than every team other than Manchester City, and no other side in the Premier League’s Enlightened Era (available shots data only stretches back to 2009-10) saved a higher percentage of attempts on goal (81). As an en vogue statistic, PDO has been surpassed by expected goals because it paints with a broad brush, but the general thought behind PDO is that, on average, a team’s shot percentage and save percentage should add up to something close to 100. Higher, and you’re likely to decline. Lower, and you’re likely to improve. Well, United had the highest PDO in the Enlightened Era last year. So, sure, historical data suggested regression was coming, but doesn’t the arc of history also bend toward United and Mourinho both winning trophies?

Through one game, that seemed like it might still hold. Despite getting outshot 13 to eight—at home—and even though they completed just three total passes within 20 yards or their opponent’s goal, United took down Leicester City, 2-1. The vital signs didn’t look healthy, but United went into the lead with a third-minute Pogba penalty, and teams do tend to concede more shots when they’re ahead.

Through two games, and, uh, yeah, this isn’t last season anymore. Brighton scored on all three of their shots on target, and it turns out David de Gea might be somewhat human after all:

Remember the part about trailing teams ratcheting up the pressure and taking more shots? United could generate only seven attempts after Brighton went ahead. On the day, they took only nine shots and put three on frame. Through two matches, United are averaging 8.5 shots per game—which would’ve been the worst number in the league last season. And it’s not like they’ve played against previously dominant defenses, either: Leicester allowed 12.9 shots per game last year (10th-most in the league), while Brighton were even more agreeable to opposing attackers (14.6, fourth-most in the league). It’s only two games, but really, it’s more like 40; the conversion rates have changed, and the underlying issues remained the same.

In attack, the plan is vaguely Arsène Wenger–esque: You guys are talented, figure it out! But while Wenger’s late-era teams lacked any sort of cohesive attacking system or aggressive pressing to boost their possessions, there was always at least some creative interplay between Mesut Özil and Co. Most top teams now press aggressively as a way of making life easier on their attackers; Liverpool manager Jürgen Klopp famously called the press the “best playmaker in the world.” It’s simple: When you win the ball back higher up the field, there’s less distance to travel toward goal and there are fewer defenders in the way. Eighteen of the 20 best attacking teams in the world last year were also above-average pressing sides.

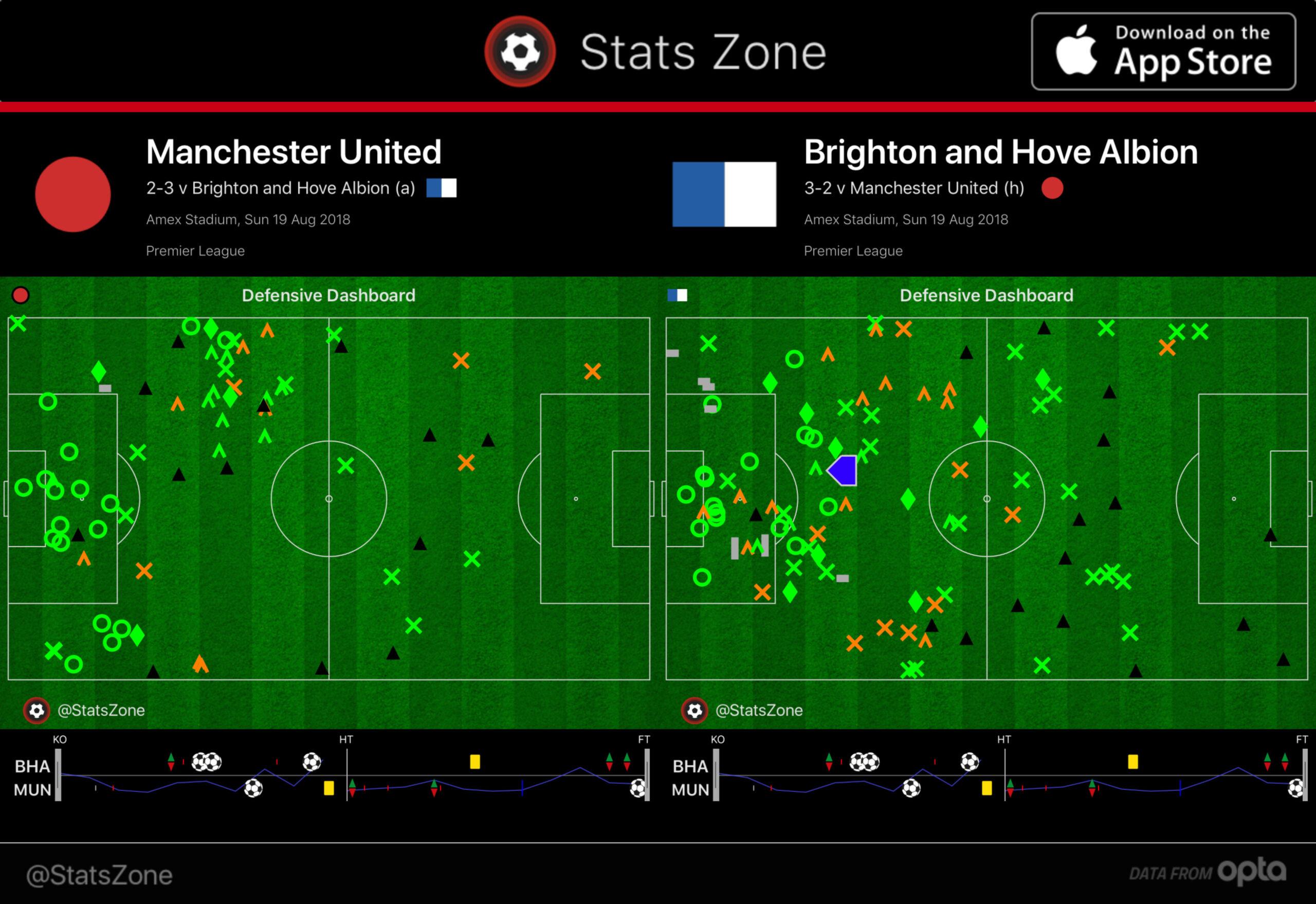

Against Brighton, United dominated possession, but they constantly won the ball back in their own half and then had an entire opposition 11 to play through. If anything, Brighton were the more aggressive defensive side. Here’s where the defensive actions occurred for both sides:

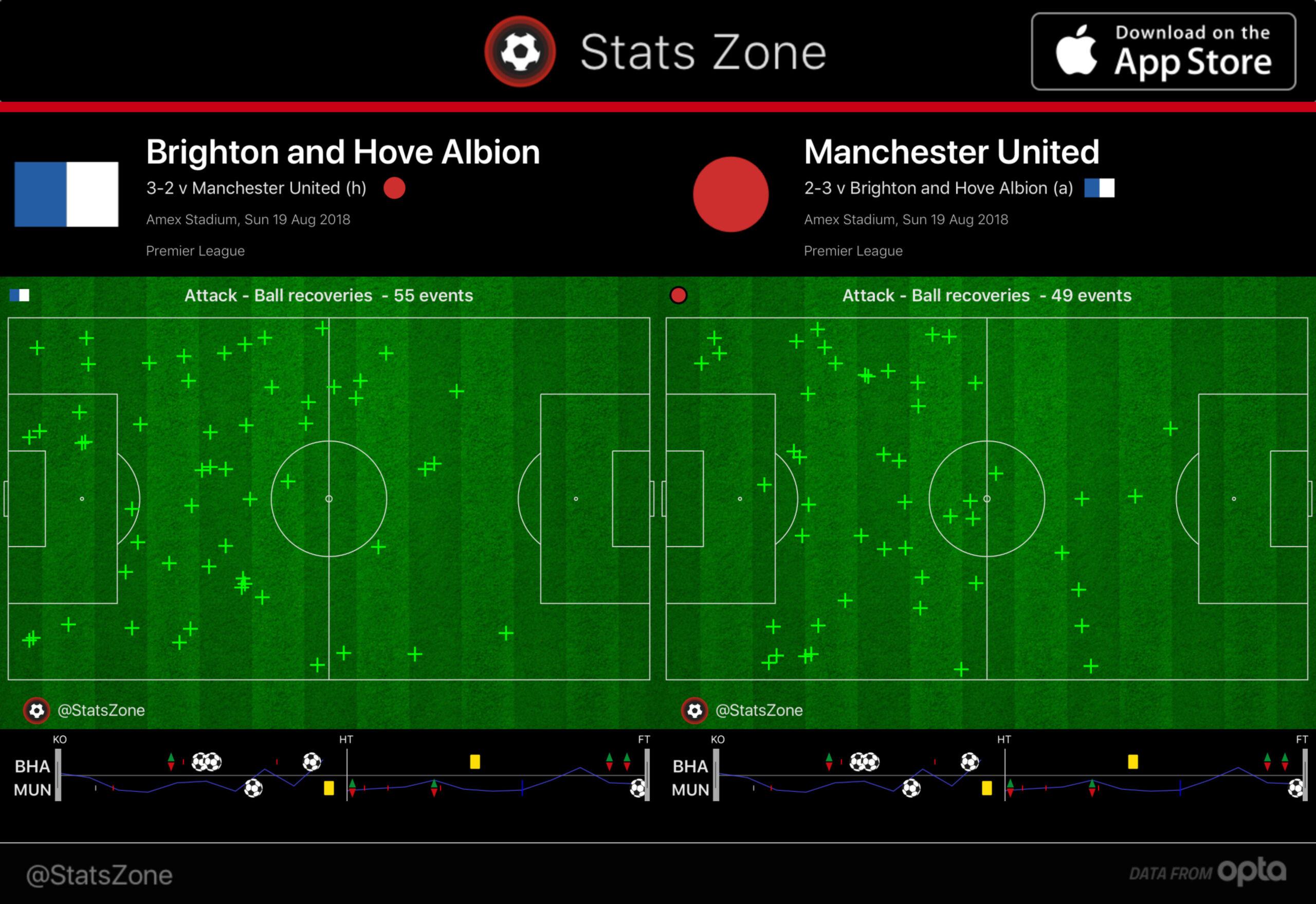

And the “ball recoveries” map tells a similar story:

With all of the talent at United’s disposal, their attack can still work, but it often feels like watching an NBA team without enough shooters to spread the floor. The decisive goals can still come—and they did in the victories against both Liverpool and Manchester City last season—but the process just seems so much harder than it needs to be. On Twitter, someone suggested to me that José Mourinho is the Premier League’s Tom Thibodeau. The current Timberwolves head coach doesn’t share Mourinho’s affection for Ermenegildo Zegna and long-winded media gaslighting, but the comparison feels increasingly right: a paradigm-shifting defensive coach who once oversaw great teams and can still produce the occasional top performance but just doesn’t have the offensive ingenuity to win enough games at the highest level.

Despite all of the consternation surrounding their quiet transfer window, United objectively still do have one of the most talented squads in the world. Except, most of that talent is attacking talent. It’s just smart strategy for a team like United, which expects to win league and cup competitions, to open the game up a little bit and plan on outscoring their opponents; soccer is random and the better team wins more often when the game’s high-scoring. But rather than trying to tilt the field and blow the Brightons of the world off the playing surface, Mourinho has United playing a conservative defensive style that implodes as soon as de Gea stops standing on his head.

Based on what they’ve (presumably) leaked to the press, it seems like the United board realizes that Mourinho isn’t the right man for the job. They supposedly vetoed most of the deals he hoped to complete this summer, noting that Mourinho wanted to bring in another big-money center back after spending on Victor Lindelöf from Benfica, then Eric Bailly from Villarreal in each of the past two summers. “The suspicion of United’s hierarchy,” The Guardian’s Daniel Taylor wrote, “is the manager is taking a short-term view rather than thinking more strategically about what would be better for the club in the coming years.” As The Guardian also reported last week, the club is now planning to appoint its first-ever director of football.

That all makes sense—until you remember that United gave Mourinho a contract extension seven months ago.

The deal was announced on January 25; United sat in second at the time, but their performances seemed like something closer to a sixth-place team. The club that is now preaching patience and long-term thinking chose to ignore the underlying warnings and focus just on the short-term results. There’s a word for that; Mourinho said it yesterday.