The upcoming MLB free-agent class has lost much of its luster. For years, baseball watchers have heard about the tectonic shift expected to come after the 2018 season, when Bryce Harper and Clayton Kershaw (assuming he exercises an opt-out clause in his contract) and Manny Machado would demand a collective billion dollars and reframe both contract thresholds and the contender landscape as we knew them. But now, as the free-agency period approaches, the class’s depth has winnowed, its secondary stars have sputtered, and with Harper struggling and Kershaw now regularly hurt, its top-tier talents haven’t matched their reputation in advance of free agency, either.

As Ben Lindbergh wrote for The Ringer last month in a piece titled “The 2018 Free-Agent Class No Longer Looks Poised to Change Baseball,” well, the 2018 free-agent class no longer looks poised to change baseball. Ben listed dozens of impending free agents who were standouts in 2015, but “whose careers have trended downward of late as age or injuries have conspired against them.” Heck, Matt Harvey was once seen as a potential jewel of the 2018 class, and as recently as this spring, Josh Donaldson—who, in his age-32 season, has hit just .234/.333/.423 in 36 injury-plagued games—was considered an easy bet to reach nine figures on the open market.

That prospective downturn, coupled with last winter’s listless market, yields reasonable concerns about the future of free agency in a sport that has seemingly devalued the practice as a means of assembling a competitive roster, in favor of an intensified focus on retaining and developing young talent. That route is smart and cost-effective and broadly befitting of an executive class with a uniformly analytical background. But free agency can still coexist alongside internal development, and the market can still matter, even beyond a 2018 class that hasn’t lived up to its billing. Despite the hyperbole that has surrounded Harper et al. for at least three years, the 2018 class might be usurped within the next three years, multiple times over. Free agency isn’t yet dead, and even another disappointing round won’t kill it.

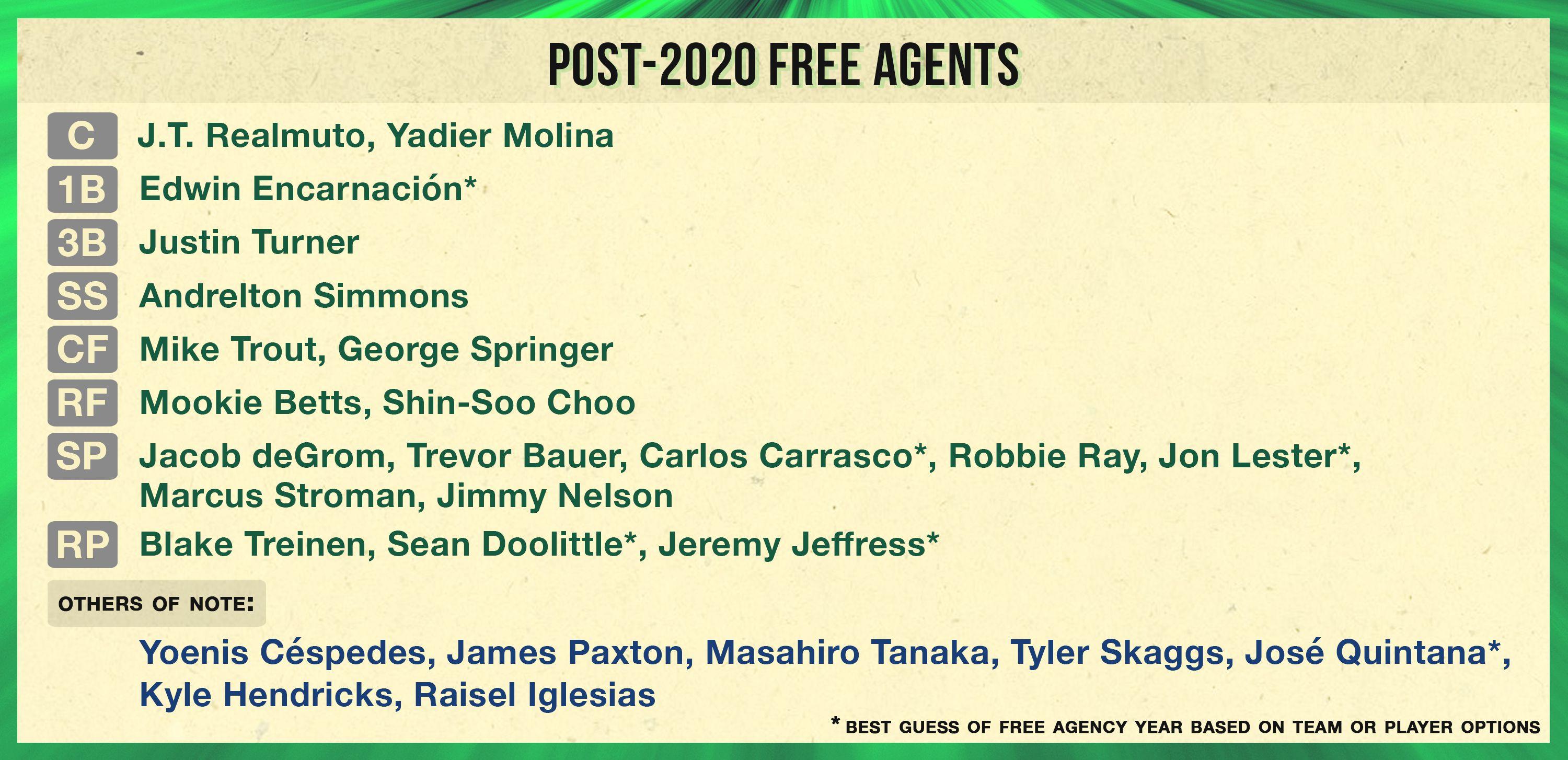

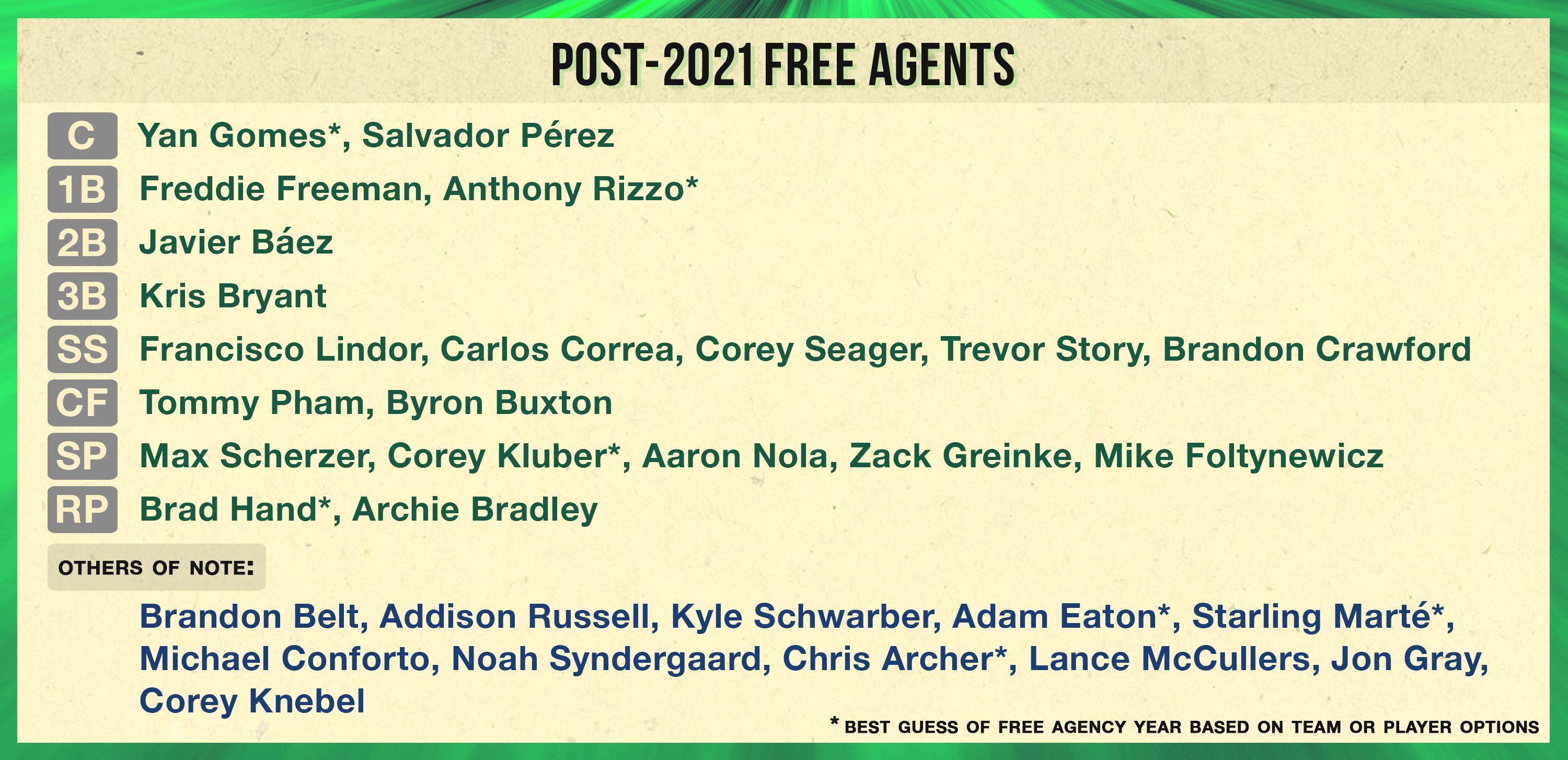

Here, by way of example, is a quick survey of the next three free-agent classes after 2018. It lists every player who either received an MVP or Cy Young vote last season or made an All-Star roster this month, plus other notable players who didn’t qualify by those criteria. (Players with one or more club or player options in their contracts appear with an asterisk beside their name. The year they appear below won’t necessarily hold, but in the interest of projecting the potential quality of the upcoming classes, these are a best guess. For instance, Cleveland’s Carlos Carrasco is subject to a $9 million club option in 2019 and a $9.5 million club option in 2020, but there is essentially zero chance that Cleveland won’t retain him at those prices, so he slots in the post-2020 class below.)

It’s not quite as impressive at the top as the 2018 class, but 2019’s comes pretty darn close. Goldschmidt and Arenado are perennial MVP contenders, while Rendon should prove a nice consolation prize for a team that aims to land Arenado but falls short. The real draw is the assortment of aces, which includes four no. 1 starters plus a fifth if Strasburg opts out of the final four years of his contract. Given their ages, they might not be the most cost-effective investments come the 2020s—Cole aside, every member of that group will be in his 30s by fall 2019—but that limitation shouldn’t stop them from demanding nine-figure deals.

This group doesn’t have the depth of the 2019 or 2021 classes, particularly among position players, but good grief, look at the headliners. Trout and Betts hitting the market in the same year would make the negotiations for Harper and Machado look like something from a Monopoly Junior session. Giancarlo Stanton could opt out that winter, too, if he plays well enough to make forgoing the remaining seven years and $218 million (at least) of his record-setting deal worth it.

Elsewhere, Realmuto could be the consensus best catcher in baseball by 2020, Simmons might be a top-three shortstop, and deGrom, Bauer, Paxton, and others provide top-of-the-rotation pitching talent; at the moment, deGrom leads all pitchers in bWAR, and Bauer ranks second to Sale in fWAR.

Anyone want a shortstop? A half-dozen All-Star-level players could be available after the 2021 season. Or how about an ace? Scherzer, Kluber, and Greinke might show their age within the next three years and become less attractive options, but then Nola and Syndergaard would still be around as younger arms worthy of the moniker.

It’s important to note, of course, that this method of projecting high-demand targets is imperfect; no general manager will clamor to sign, say, Choo or Jeffress after 2020. And projecting potential demand multiple years out is also inherently inexact, as the perceptual demise of the 2018 class illustrates. But even after discounting flukier All-Stars and aging greats, as well as accounting for attrition at this level—Ben found that only about 40 percent of All-Star-caliber players are still that valuable three years down the line—there is still plenty of talent remaining. In the interim, new and unexpected stars will arise, too, as Diamondbacks pitcher Patrick Corbin has in the 2018 class.

The fundamental shift driving this pattern is a growing disinclination among the game’s best young players to sign long-term extensions. The early extension trend began in 2008, when Evan Longoria inked a lengthy offer from Tampa Bay just six days into his MLB career; in consecutive springs from 2012 through 2014, Bumgarner, Sale, and Trout signed well-below-market-rate deals that bought out years of free agency. But just a decade after the trend began, it’s gone out of style. Stars like Lindor and Machado have steadfastly rebuffed extension overtures to date, and while early deals still exist, they’re more often falling to players at the Paul DeJong and Tim Anderson level.

This change yields obvious repercussions on the free-agent circuit, as extensions serve to dull the impact—and, therefore, the excitement—of free agency. Trout, Goldschmidt, and José Altuve could have all been free agents this past offseason had they not signed team-friendly extensions; the market wouldn’t have slumbered then. Moreover, players who reach free agency at a younger age are more likely to maintain their performance level longer, and thus attract more lucrative offers. Harper and Machado won’t set contract records this winter just because they’re generational talents; they’ll also both be 26 years old, presumably with years to go until they start to decline.

Due to their robust financial histories in baseball, many of the young players on the above lists have less immediate incentive to commit to an extension in which they’d trade fewer total dollars for more long-term security. As FanGraphs’ Dave Cameron wrote of this trend last spring, “None of these guys need a long-term deal to get financial security. They’re already there.” Consider the young Cubs, five of whom could populate the 2021 free-agent class. Among Báez, Bryant, Russell, and Schwarber, the player picked the lowest in his respective draft was Russell, who still went 11th overall, and each member of that quartet made at least $2.6 million in a post-draft signing bonus. Meanwhile, Rizzo went in the sixth round of his draft and received a mere $325,000 bonus—and he’s the one member of Chicago’s core who signed an early extension.

Houston, similarly, has impending free agents in Cole and Correa (both first overall picks), plus Springer (11th), McCullers (41st), and, further down the line, Alex Bregman (second). All of those players received at least $2.5 million before playing a minor league game. Altuve, like Rizzo, signed an early extension because he had received just $15,000 as an international free agent out of Venezuela.

Beyond Chicago’s and Houston’s rosters, Harper was a no. 1 overall pick; Buxton went second; Machado, Bauer, and Gray went third; Rendon went sixth; Nola and Bradley went seventh; Lindor went eighth; and Conforto went 10th. Even injury-prone pitchers like Paxton and Syndergaard have yet to engage in meaningful extension talks, which is a break from recent precedent. As Cameron wrote, “We have an amazing group of young arms in baseball right now, and despite the health risks that come from throwing the ball for a living, almost none of the high-end guys have taken early-career certainty in the form of a long-term deal.”

Of course not all of these players will continue to push aside long-term security, and all it takes is one Trout or Betts extension to make the potential 2020 free-agent class a whole lot less effulgent. Just as injury and performance decline will rob future markets of some stars, so too will the inevitable deals signed by players approaching free agency, even if they’re not of the team-friendly variety to which the sport has become accustomed (e.g., Charlie Blackmon’s pact with Colorado from earlier this year).

The general direction is away from early extensions, though, and if franchise cornerstones begin reaching the open market at accelerating rates, the sport will experience several notable ripple effects. First, free agency still won’t be an optimal way to build a cost-effective team—but for some franchises, it could prove the best way, or at least a way, to acquire stars. Second, it could help break the bond of the “superteams” currently overrunning baseball’s win columns. Collectively, the players who produced more than 90 percent of the positive WAR for last season’s playoff teams returned to their respective rosters in 2018—a historically high ratio—but that data point won’t turn into a pattern if contributors are free to leave winning teams.

Third, it could make money matter again as a strongly deterministic factor driving win totals. The strength of the relationship between payroll and winning percentage has been on the rise after a relatively down period in the first half of this decade, and if free agency is once again going to make acquiring an elite player as easy as submitting the richest bid, it’s reasonable to expect the wealthiest teams to prosper most, even if assembly of a superteam exclusively through free agency would still be out of reach given the probable prices involved. For evidence, look no further than the sport’s actual wealthiest teams: The Yankees and Dodgers painstakingly cleared 2018 payroll, with the latter engaging in as tricky a bit of sports bookkeeping as you’ll find this side of Daryl Morey, with the sole purpose of resetting their luxury-tax rate in advance of an upcoming spending spree. Then there’s the Phillies, who could try to sign both Machado and Harper this winter; what if a team makes a play for Sale and Arenado the following year, or even Trout and Betts in 2020?

This potential trend doesn’t mean that the squeezing out of baseball’s middle class isn’t a real and vital concern, nor that baseball’s overarching financial system—which rewards most players after they’ve passed their primes while grossly undercompensating young players who are contributing the most—isn’t in need of a broader reimagining. Labor strife might still come. But 2018 won’t be free agency’s last breath; if you send stars to the market, the dollars will come, and it looks like the stars will align every winter for years.