How an ‘Overwatch’ Update Derailed One of the Most Dominant Teams in Esports

The New York Excelsior looked like they might cruise to a title in the inaugural season of the Overwatch League—until Brigitte came along

This week was supposed to be a triumphant one for the New York Excelsior, the Overwatch squad that until recently was one of the most dominant teams in esports. For most of the first season of the Overwatch League—a pioneering, geolocated competition featuring Blizzard’s online, objective-based, six-on-six shooter—the all-Korean Excelsior, formed from the bones of a pre-OWL crew called LW Blue, easily dispatched their opponents. In the months after the league launched in January, the Wilpon-owned NYXL established themselves as overwhelming favorites to take the inaugural title, and when Blizzard announced in May that the finals would take place at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn later this week, the stage seemed to be set for the Excelsior to compete for the crown in front of a sold-out, sympathetic crowd and a large streaming audience on Twitch and Disney channels. Like the rest of the league’s 12 teams, which are ostensibly based in cities across three continents, the Excelsior spent the season at the Blizzard Arena in Los Angeles, but the final act of their championship story was slated to unfold in their adoptive home.

Then, late last week in the OWL playoffs, the almost-unthinkable occurred: The Excelsior lost in the semifinals, defeated 3-0 and 3-2 on Wednesday and Saturday, respectively, by the Philadelphia Fusion, who finished sixth in the four-stage regular season, barely clearing the cutoff for the six-team playoff pool. In the finals this Friday and Saturday, the Fusion will face the fifth-place London Spitfire, as the seemingly unbeatable Excelsior follow events from the sidelines. As shocking as that playoff upset was, though, the Excelsior’s downfall dates to a change in the game that Blizzard made in May. From that point forward, competitive Overwatch wasn’t the same—and neither were the Excelsior, who were slow to adjust to the new prevailing tactics in a fledgling league whose competitive underpinning moved with disorienting speed.

Only in esports could strategic circumstances shift as drastically as they did in the Overwatch League from the start of a season to the end. As we wrote in mid-April, the competitive conditions—or as they’re often referred to in esports, the metagame, or “meta”—in the OWL up to that point had favored the “dive comp” approach. In dive comp, players select fast-moving heroes such as Winston and Tracer and “dive” behind enemy lines in coordinated strikes, ganging up on and destroying their opponents’ isolated support players while their slow-moving and powerful “tanks” are elsewhere on the map.

This strategy served the Excelsior well: As New York coach Hyeon-sang “Pavane” Yu told us at the time, “We do consider ourselves specialists in the dive-tank strategy.” In each of the regular season’s first three stages, NYXL went 9-1, amassing a map differential of at least plus-21. (Overwatch matches consist of four—or, if a tiebreaker is required, five—rounds, each of which takes place on a different map.) The Excelsior’s cumulative plus-68 map differential at the end of Stage 3 dwarfed London’s second-place plus-38. But unfortunately for the Excelsior, dive’s days were numbered.

Because the dive approach had proved so effective, the strategy crowded out alternative tactics, and the variety in playstyles and hero use that Overwatch had been designed to foster gave way to a discouraging sameness and some spectator fatigue. As the usage rates of the heroes best-suited to dive comp climbed, Overwatch principal game designer Geoff Goodman acknowledged to us that Blizzard was considering changes. “It’s not like, ‘Man, we want to kill this dive meta really bad,’ but it is sort of a concern when we have hopefully all these other potential viable strategies as well sort of being under-utilized,” Goodman said. “We want there to be other strategies [that are] equally used and popular.”

As we noted in April, Blizzard had recently introduced a 27th hero, Brigitte, whose attributes seemed calculated to neutralize dive comp. Brigitte is a healer, which means that she tends to stay in the background and support more offense-oriented characters. In that sense, she fits the profile of a perfect dive victim. But unlike some easier support targets, Brigitte can defend herself against dive by stunning attacking characters with her shield. That stun effect lasts for only one second, but because dive’s success is often predicated on speed, that delay is often long enough for a more powerful character to arrive. In some cases, Brigitte can use a combo to stun and then defeat a diving opponent herself, especially if the attacker is a low-health hero such as Tracer. Pavane told us that Brigitte was “very effective against dive comp,” which led us to conclude that “dive comp may be on its way out as a dominant strategy.”

At the time, Brigitte was usable by non-professional players but hadn’t yet been introduced to OWL action. (Blizzard often deploys patches in amateur competition first to minimize the risk of destabilizing the sport at the most elite level.) But starting with Stage 4 in mid-May, Brigitte became an option for OWL players also—and very quickly, many of the world’s best Overwatch players embraced Brigitte as an antidote to dive. Just as a January 2017 patch had paved the way for dive to dominate Overwatch competitive play, the patch that brought in Brigitte contained the seeds of dive’s demise—and, by extension, the Excelsior’s.

Since Brigitte debuted in OWL on May 16—somewhat controversially without a nerf that had already weakened her abilities in non-OWL play—teams using Brigitte against enemies not using Brigitte have a fight win rate of 54.1 percent, according to data from Overwatch stats site Winston’s Lab. That’s the highest win rate of any hero with more than one hour played. Consequently, Brigitte’s popularity has increased across the league, which has lengthened the average fight by almost one second (or about 5 percent), reflecting the game’s shift away from the frenetic dive style.

In a macro sense, Blizzard’s intervention had the intended effect. Prior to Brigitte’s OWL arrival, 12 heroes had pick rates higher than 10 percent, five heroes were chosen more than 75 percent of the time, and the dominant 2-2-2 team configuration—two attack-oriented heroes, two tanks, and two healers—was used about 90 percent of the time. The latter two figures fell in Stage 4, and since the most recent patch at the start of the playoffs earlier this month—which dealt an additional blow to dive by buffing (or augmenting the abilities of) Hanzo, a sniper hero who deals damage from afar and thus doesn’t tend to dive—15 heroes have a pick rate higher than 10 percent, and only two have topped 75 percent. Likewise, the 2-2-2 team configuration has been used only 46 percent of the time. Competitive Overwatch has become a less predictable and more stylistically diverse game.

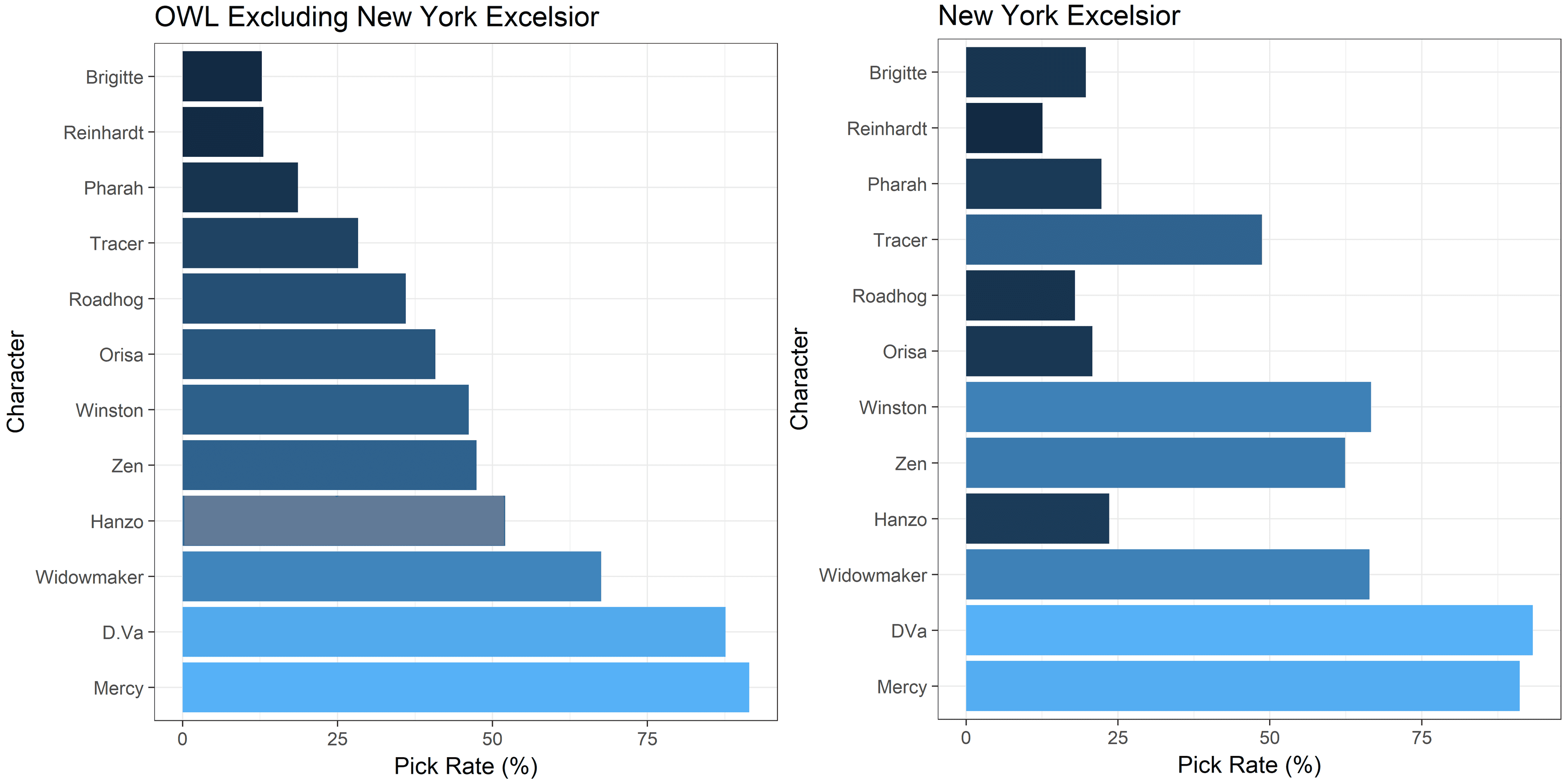

The Excelsior didn’t adapt to those developments. Across the league, OWL pick rates for the top 10 characters each month have changed by an average of 24 percent from March to July. NYXL’s pick rates changed by 19 percent over the same span. In March, the Excelsior were within 5.2 percent of the league-average pick rates; by July, they were 8 percent away from those baselines. As the rest of the league began to abandon the 2-2-2 configuration in favor of post-dive lineups with three tanks or support heroes, the Excelsior stuck to their old look about 60 percent of the time. As the league as a whole raised its usage of Brigitte, Hanzo, and Orisa (a tank hero who became more effective post-patches) by roughly 25 percent, the Excelsior largely shied away from those characters, using Brigitte only 10 percent of the time in June compared to 33 percent for the league as a whole. The charts below reveal how little the Excelsior’s usage of buffed heroes Brigitte and Hanzo changed in recent months compared to that of OWL teams other than the Excelsior.

Other teams took advantage of the Excelsior’s inertia, which may have been exacerbated by the midseason departure of director of player personnel Scott Tester, who left in late April to take over Team USA in the Overwatch World Cup. Although NYXL still enjoyed some success in Stage 4, they were more beatable than before, trailing two other teams and finishing 7-3 with a plus-15 map differential, worse than they’d done in any of the previous stages. Overall, the Excelsior won a league-leading 55.2 percent of their fights pre-Brigitte but emerged victorious from only 48.5 percent of their fights in June. That month, three teams used Brigitte against the Excelsior more than they did overall. In the semifinals, the Excelsior won only 42.2 percent of their fights against the Fusion, who netted 59 additional kills compared to the Excelsior. Of those 59, 32 came when NYXL was using Tracer, and 12 came when Philadelphia was using Brigitte (counting only fights in which the number of ultimate abilities used was the same on both sides).

In one sense, the Excelsior’s unwillingness to adapt along with the league is understandable. No team had flourished like the Excelsior under the conditions that favored dive, which means that no team had as much potential to sabotage itself by tampering with its tried-and-true formula. In light of the squad’s dominance throughout most of the season, the Excelsior—who didn’t respond to an interview request after their loss—may have figured that they could overpower opponents even if evolving conditions had compromised their original approach. Moreover, the Excelsior’s star support player (and regular-season league MVP) Seong-hyun “JJoNak” Bang specializes in playing Zenyatta, a hero who helps orchestrate dive attacks and heal heroes who are diving.

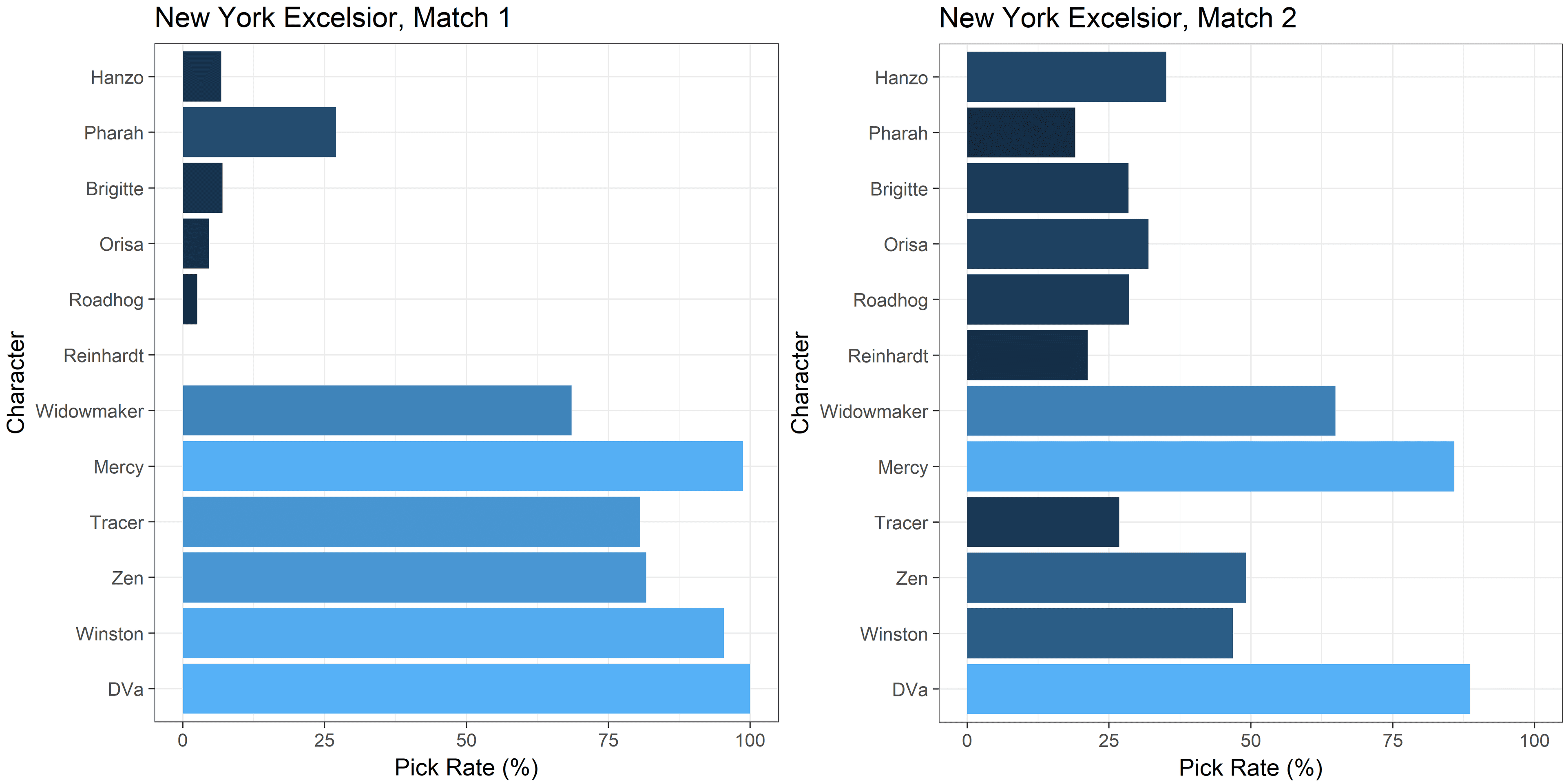

As it was, the Excelsior used Hanzo only 6.8 percent of the time in their first playoff matchup against the Fusion (less than half the playoff average) and Tracer 80.6 percent of the time (more than twice as high as the playoff average). Unlike London and Philadelphia, the Excelsior’s tank players at first almost exclusively selected dive-oriented options D.Va and Winston, and the team initially opted for Orisa and Roadhog about half as often as the league as a whole. Perhaps stung from being swept in that first tilt with Philadelphia, the Excelsior aggressively shifted away from dive in their second, decisive semifinal matchup, using Brigitte, Hanzo, Orisa, and Roadhog much more often and reducing their reliance on Winston, Tracer, and Zenyatta. The graphs below show how dramatically NYXL moved away from their typical alignment in their last-ditch effort to save the season.

Although the Excelsior fared better in that second match, those adjustments were too little and too late. Judging by a post-match tweet from NYXL support player Yeon-jun “Ark” Hong, the new tactics may have left the players feeling unprepared. And even after their mid-playoffs adjustment, the Excelsior’s overall playoff hero selection was still out of step with the rest of the playoff field, as the following charts reveal.

Although some Excelsior players had ample experience with popular playoff picks such as Hanzo, Orisa, and Roadhog and could have pivoted to those heroes in the playoffs even more often than they did, JJoNak, who anchored the crew while playing Zenyatta more than 90 percent of the time during the regular season, might have had a harder time adjusting regardless of what tactics New York tried. That conundrum made the Excelsior vulnerable, and their playoff opponents sensed their weakness. “I feel like now, dive is not much of a thing, and when it is, Brigitte is really strong and it is much easier for me to compete with [JJoNak],” Fusion support player Isaac “Boombox” Charles said in an interview last week following Philly’s first win against New York. “Whereas before, he and his team excelled in playing dive style, so I feel like he is not as strong as he was before.”

For Richard Ng, who founded the Excelsior supporters club the 5 Deadly Venoms and was one of several hundred fans who gathered to watch Saturday’s loss at The 40/40 Club in New York’s Flatiron District, the Excelsior’s exit on the verge of the finals was painful. “It hurts that they’re not there,” Ng said via direct message. Ng wondered why the Excelsior neglected Brigitte and Hanzo, but he also questioned Blizzard’s decision to change the game so significantly on the eve of the playoffs. “The challenge for the league that needs to be considered is [that] the perception of team strength and skill [could be] based on their changes to the software more so than the team strategies,” Ng says. “That’s a bit concerning since the ability to succeed … can just be eliminated with a patch change. [It’s] tough to build a strategic culture around that.”

It’s natural for an Excelsior supporter not to be thrilled about the rollout of updates that partially neutralized the team’s attack, but even independent of rooting interests, tinkering with the way a sport works toward the end of a season is a dangerous thing to do. The Excelsior developed a dominant tactic, and then that tactic stopped working as well—not because their opponents learned to counter it, but because the game itself changed in ways that worked against them. As “Boombox” said in the same interview, “It has been a drastic change in a short period of time.”

Esports developers face a dilemma that traditional leagues typically don’t: A company like Blizzard has to weigh the impact of each change on both pro-level competitors and the amateur players who make up most of their audience. Balancing games for both audiences without making them play so differently that the amateurs no longer recognize the game they’re familiar with when they watch the pros play is, as Goodman told us in April, “the big trick. … It’s something we wrestle with basically constantly with every change we go through.” Blizzard declined to comment on this quandary in the wake of the Excelsior’s loss, citing executives’ busy finals-week schedules.

As longtime esports journalist and broadcaster Rod “Slasher” Breslau explained via direct message, “Developers changing the balance of the game right before a major tournament is a discussion many different game communities have had in recent years.” Breslau noted that while some games, such as Dota, have succeeded in either limiting major changes leading up to important events or implemented tweaks that have been nearly universally praised by amateurs and experts alike, “Blizzard’s Overwatch team in general has not done the best job in communicating to pro players ahead of time what changes may be coming, and the changes themselves have been highly contested among the professional scene.”

Given that esports haven’t had decades or centuries to work out their competitive kinks as many traditional sports have, it’s a selling point that the games can change on the fly to address player and spectator concerns. But it also makes it more difficult to count on the best team today being the best team tomorrow. Blizzard defusing dive in Stage 4 is akin to the NBA removing the 3-point line 60 games into its season. Perhaps a sport that’s featured the same finals matchups four years in a row could benefit from an injection of the OWL’s unpredictability, but one could understand why a great team that constructed its roster and game plan around sinking 3-pointers might be miffed.

The OWL’s more mercurial nature places a premium on adaptability, and in the long run, the Excelsior weren’t nimble enough. As Breslau observed, “All the teams had to go through these balance changes, so it’s not like it was just [the Excelsior]. Due to how far ahead NYXL was in the standings and a confirmed first seed going into playoffs a month before it started, they even had a much longer time than all other teams to practice the new patch, test out different lineups, and adapt. … But as shown in their games vs. Philly, they never got it together.”

Although the Excelsior’s Latinate team name translates to “Ever Upward,” their climb stalled too soon. The NYXL were the best team in the Overwatch League for the bulk of its first season, but by the end, they weren’t, at least not when they needed to be in their games against the Fusion. Both Philly, which shifted to mix between triple-support and triple-tank lineups, and London, which went all in on triple-support, took to the game’s patches more readily, and as a result, one of the visiting teams on the Excelsior’s turf will be rewarded with a $1 million bonus, while the runner-up will take home $400,000. (The Excelsior’s semifinal exit added $100,000 to their 2018 earnings.) But next year will bring a new season—and, depending on the patches, perhaps partly a new sport.