“We’re in This Amazing Golden Era of Documentary”

For the first time in years, docs are thriving at the box office. Some are political, some personal, and some merely a beautiful diversion. Why has the form become so essential to modern movies? Filmmakers and producers talk about the moment and address whether it can keep growing.An 85-year-old Supreme Court justice. A pastor with a public television show. Identical triplets separated at birth. A songbird gone too soon. A pope. Pandas.

It isn’t a bad joke or the line at the post office that unites these figures. It’s documentary—six to be exact, all of which have been released to theaters this year, and all of which have earned at least $1.5 million at the box office. RBG, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, Three Identical Strangers, Whitney, Pope Francis: A Man of His Word, and Pandas represent, if not a major moment, then at least a meaningful boomlet for theatrical documentary filmmaking, perhaps the culmination of almost 50 years of evolution and exposure for the form, stretching back to the Maysles brothers’ Salesman. It has been 40 years since Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz, about 30 years since Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line and Michael Moore’s Roger & Me, nearly 25 years since Steve James’s Hoop Dreams, 20 years since Spike Lee’s Four Little Girls, and 10 years since James Marsh’s Man on Wire. That half a century of meaningful work with increasing mass exposure has slowly redefined the form, turning what had been considered by some moviegoers a starchy, stiff form of storytelling into some of the most vital, sought-out films in the country. They are bid upon at festivals with a new vigor, reviewed with aplomb, and seen with more frequency than ever. Somewhere along the way, docs became, well, content.

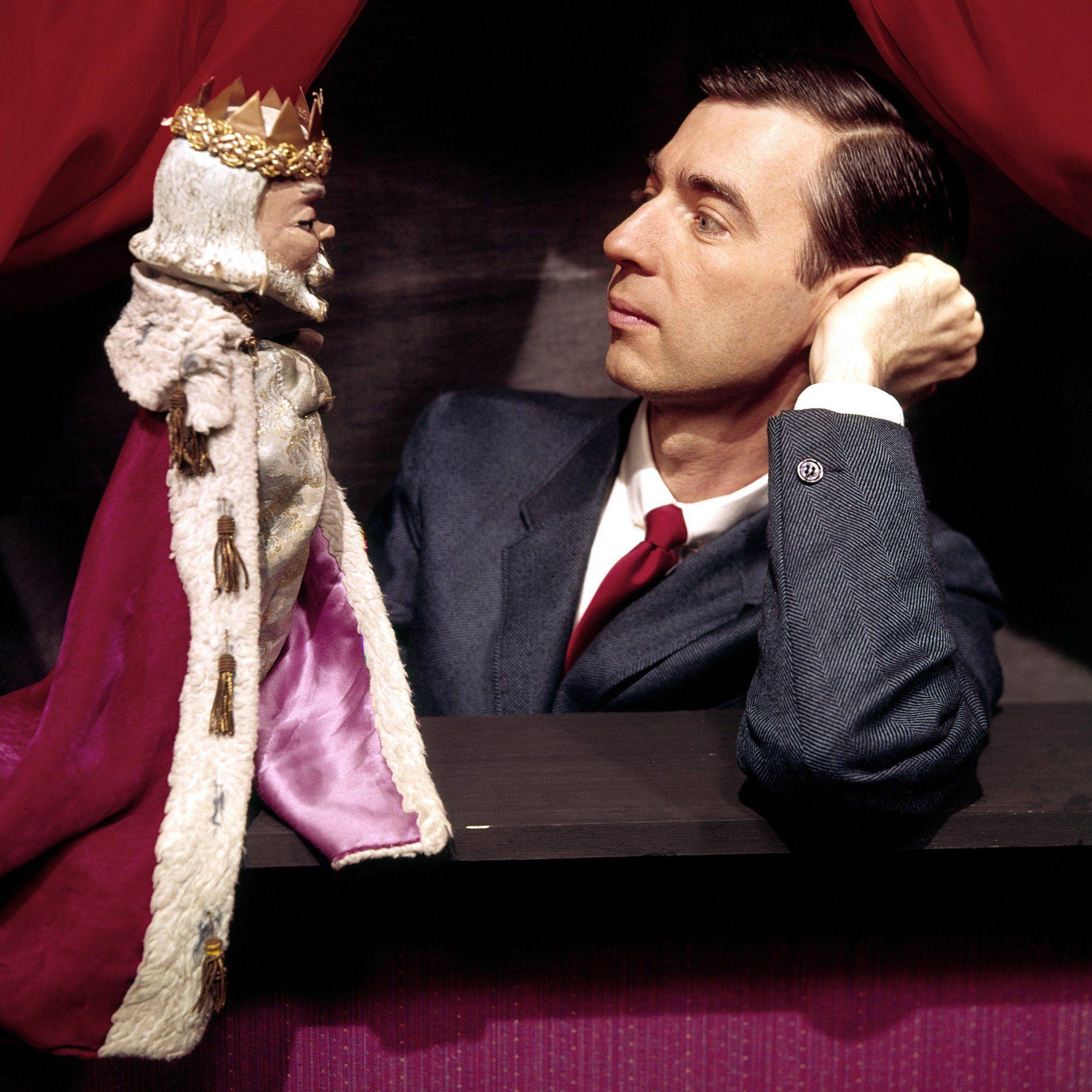

“When I started, documentaries were like the spinach of filmmaking,” says Morgan Neville, the director of this summer’s biggest doc hit, the Mister Rogers film Won’t You Be My Neighbor? “Nobody cared about them. Nobody wanted to pay for them. They weren’t sexy. Now we’re in this amazing golden era of documentary and nonfiction storytelling that just keeps getting more interesting.”

It wasn’t that I wanted to go back and revisit the nostalgia of Mister Rogers. It was like, ‘I need Mister Rogers in 2018. Who’s the grown-up in our society?’Morgan Neville, director of Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is an extraordinary anomaly, earning $18 million and counting, passing prefab products like Disney’s animal-centric films Bears, Monkey Kingdom, and African Cats and approaching the likes of glossy pop-star-driven vehicles like Katy Perry: Part of Me and One Direction: This Is Us. Neville’s movie, which is distributed by Universal’s Focus Features, is already the 14th-highest-grossing doc of all time, with an outside chance at reaching the top 10. But unlike the polemical films that top the upper echelon—including Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 ($119 million) and the recently pardoned Dinesh D’Souza’s 2016 Obama’s America ($33 million)—Neighbor is told in a straightforward, unfussy way, using standard head-on interviews, archival footage, and an utter lack of regard for austerity to render a movie that is by turns soft-bellied and soft-hearted. It has been bandied about as an act of defiance in the face of a noisy, angry presidential administration, a whoosh of radical kindness to remind viewers of a time before ALL-CAPS TWITTER TIRADES.

“One night, I somehow ended up on a YouTube deep dive of Mr. Rogers’s speeches,” Neville told me. “It was like one of these epiphanic moments—‘I want more of that voice. I don’t hear that voice anywhere in our culture right now.’ It wasn’t that I wanted to go back and revisit the nostalgia of Mister Rogers. It was like, ‘I need Mister Rogers in 2018. Who’s the grown-up in our society?’”

The late documentarian Albert Maysles—who made sympathetic figures out of door-to-door Bible salesmen, decaying shut-in aristocrats, and the IBM corporation—once said, “The film is sort of the beginning of a love affair between the filmmakers and the subjects. Some filmmakers make targets of the subjects they film; that’s not our way.” Neville’s film has that in common with RBG, Julie Cohen and Betsy West’s warm, meme-centric portrayal of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Their film is largely hagiography, an access-driven vision of a beloved, tireless activist jurist with a staggering record as a legal advocate for equal rights. It is dotted with nods to Her Honor’s viral late life, including the Notorious RBG moniker, Kate McKinnon’s caricature on Saturday Night Live, and her willed-from-dreams participation in the opera. Its tone is fizzy for biography, even peppy at times. RBG, which was financed by CNN Films and distributed by Magnolia Pictures, is not a breakthrough for the form—but its success has no precedent. (As a minor thought experiment, imagine a film of this kind about Bader Ginsburg’s longtime benchmate Stephen Breyer. Impossible.) The movie’s $13 million gross makes it the second-biggest single-subject, non-pop-star biodoc ever, coming in just behind Neighbor. It’s reaching audiences beyond the normal doc crowd.

“We have to go into something believing that there is an audience that will come to it, and not just your typical arthouse, New York–L.A. audience,” says Courtney Sexton, vice president at CNN Films. “We really are looking to find projects that will resonate in middle America because that’s where our brand is, in our channels in homes across the country.”

RBG has a slick, well-timed calculation to it, but it is handmade and rigorous, too. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is an openly, eagerly, almost mercenary emotional viewing experience. Together, they make a pair of political moviegoing experiences—a history lesson about sincerity and an art project about the law—using totemic figures to make their points. Along with Tony Zierra’s attentive, slavish Filmworker; Kevin Macdonald’s ghostly and sad Whitney; Eugene Jarecki’s questing The King; and Wim Wenders’s Pope Francis, the year has been rich with docs examining the living remains of looming giants and pop cultural institutions—Elvis, Kubrick, God, etc. Asif Kapadia’s Amy, the much-seen, much-admired Oscar winner about the late Amy Winehouse, appears more and more to be among the most influential theatrical docs of the decade. It was both a success and a lesson: If your movie’s hitting theaters, lean into the known.

About that: The documentaries that are thriving in theaters probably have TV to thank. A swell of factors in recent years that includes HBO’s commitment to the form, PBS’s unwavering work with POV, ESPN’s 30 for 30 series, and Netflix’s belly flop into the deep end in the past five years has created a new kind of viewer cadence. Last year’s Academy Award winner for Best Documentary, Icarus, originated on Netflix after premiering at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. The year before that, the winner—Ezra Edelman’s sweeping OJ: Made in America—was largely seen on ESPN. Over time, documentaries became not just consumable and easily attainable, but rewatchable. Somewhere along the way in my life, I began to use Best of Enemies—Neville’s spiky, staccato film about the rivalry between Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley—as my personal night-light, firing it up on Netflix when I want to be half-engaged before nodding off. Once upon a time, movies like Clerks and Reservoir Dogs occupied that role in my life. Now it’s filled by two cranky, bickering intellectuals.

This documentary takeover has expanded to series. Once upon a time, Jean-Xavier de Lestrade’s miniseries The Staircase was an outlier among longform doc storytelling. This year alone, Netflix has released Wild Wild Country, Flint Town, and Evil Genius: The True Story of America’s Most Diabolical Bank Heist, along with anthology doc shows Rotten, Dirty Money, and David Chang’s Ugly Delicious. HBO has rolled out projects about Garry Shandling and Robin Williams, The Ringer’s own Andre the Giant film, another Elvis movie, and soon, a film about Jane Fonda. Starz has America to Me, a series coming from the iconic filmmaker Steve James, so many years after Hoop Dreams. Showtime had a doc series about The New York Times. FX has one of those, too. Oh, and Netflix revived The Staircase for a pair of capstone episodes on the infamous case of Michael Peterson and his dead wife, Kathleen. This is barely a toe dip into the ocean of documentary work on networks and streaming services in 2018. Documentary as a whole isn’t just booming. It’s bursting all over the media landscape.

But its success in theaters is still unique. Ticket prices are up, options are vast, and the in-house competition from comic-book sequels is getting bigger and stickier by the moment. For more than a decade, there was one, or maybe two, bigger releases in the field per year. An indelible Errol Morris exploration or Alex Gibney movie. Maybe an inexplicable sensation like March of the Penguins. Or a brilliantly executed stunt like Exit Through the Gift Shop. These sorts of movies seem to be happening all the time now, all at once.

“When I was learning my trade as a development guy, but also as a director, the bar for theatrical docs—the stories that would justify the expense of a theatrical documentary—was huge,” says Three Identical Strangers director Tim Wardle. “It was like, One Day in September, Touching the Void, Man on Wire. It had to be at that level before it felt justified in asking people to go into a theater and pay money to see it. And I think what has changed since then is, the technology has become a lot cheaper and the editing software has become a lot cheaper. So there’s a lot more people making theatrical docs, or theatrical-length docs, and when you go to festivals now there are hundreds of them.”

These sort of stories are better than fiction and take twists and turns that you couldn’t believe.Courtney Sexton, CNN Films vice president

Many of the docs that have begun to play festivals and fill streaming services are cause-first films that ply the viewer with tales of woe and societal rot, often told in modest terms. Think longtime Netflix staple Fat, Sick and Nearly Dead. Sometimes they’re anthropological, like the photographer Lauren Greenfield’s fascinating upcoming look at the moneyed in America, Generation Wealth. And sometimes they can change the way things work in the world, as in Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering’s The Bleeding Edge, which debuts on Netflix this weekend. But Wardle’s movie is different. It isn’t an issue film or a hagiography. It isn’t true crime, exactly, or a concert movie. It isn’t polemical and isn’t funny. It is story-driven, plain and simple. A corker. Three Identical Strangers, which opened in late June, is difficult to explain if you haven’t seen it because watching the narrative of three brothers reuniting and then learning the fateful truth about their separation unravel is the whole point. And part of what makes it a tougher sell than its contemporaries.

“To market the film, you have to give away some of the things that will make it exciting for people to see cold,” says Wardle, a longtime producer and development executive at the British production house Raw TV. “It is a challenge. If you’ve got Mister Rogers or RBG, you just put them on the poster and that’s your marketing campaign, whereas our film is the story, and it’s like, how much of that do you want to give away in advance? I always knew that the story, if we could get enough people to see it, would sell itself. Because it’s the kind of film that you leave wanting to have a conversation about.”

People are talking. The movie has made nearly $5 million in just 322 theaters around the country. It is a rousing critical success, with high audience approval, strong word-of-mouth, and a likely Oscar nomination. Last week it was announced that the doc is being adapted into a feature film. This past weekend, it passed the woeful Gotti to become the 80th-highest-grossing movie of the year, a fitting turnabout from one East Coast scandal to another. In the doc space, it’s a unicorn.

“Three Identical Strangers is always something that we’re looking for, and honestly the hardest to find,” says CNN’s Sexton, whose company financed the film and partnered with Neon for distribution. “These sort of stories are better than fiction and take twists and turns that you couldn’t believe. Those stories are much harder to mine, and find, and then to have the benefit of having three young guys who look exactly alike, to have this visual marketing hook. It was just a dream to be able to find.”

People are going and seeing these documentaries and having an emotional experience, whereas maybe previously, in the last few years, it’s been more of an intellectual experience.Tim Wardle, director of Three Identical Strangers

Three Identical Strangers was not an overnight success. Wardle developed the story for five years, negotiated extensively for the brothers’ participation, and struggled to raise the money to make it. And given the story’s incendiary, fascinating twists, there were hurdles, too: Three different networks had attempted to tell the brothers’ story before, twice in the 1980s and once in the ’90s, each time falling short of pulling it off. The reasons are shrouded, but once you’ve seen the movie, you’ll understand the practical and legal difficulties. The stakes are high.

“I watched [Won’t You Be My Neighbor?] with an audience, and I think the emotional reaction you see for that is extraordinary as well,” Wardle says. “I think if there was a common theme between my film, RBG, and Rogers, it would be that they’re foregrounding emotion and seeking an emotional truth I think may have been more in the background in recent years in documentaries. People are going and seeing these documentaries and having an emotional experience, whereas maybe previously, in the last few years, it’s been more of an intellectual experience.”

Neville can recall a time when things were even more difficult.

“Just a quick history of documentary when I think about it: There was the end of the VHS market, pre-DVD takeoff,” he says. “Then there was a moment in the early 2000s, where Michael Moore and Spellbound and a few films did really well theatrically. Suddenly, there was a lot of equity money to make documentaries. Then a bunch of those films didn’t make money, so the equity money went away. Then the DVD market came in strong, and you could finance films based on projected sales of DVDs. And then that disappeared. Then finally, the streaming market came in and kept changing it.”

It keeps changing it. August will bring 30-year-old Bing Liu’s astonishing, wrenching Minding the Gap, about a crew of teen skaters in Illinois coping with growing up. It’s perhaps the most praiseworthy project Hulu has yet launched. CNN and Magnolia, the same pairing that delivered RBG, have Love, Gilda, a straight-ahead depiction of the iconic SNL performer Gilda Radner, coming to theaters in September. There are docs coming on John McEnroe and the designer Alexander McQueen. There’s one on Scotty Bowers, the legendary Hollywood sexual procurer to the stars. They’re going to space and they’re going to the ballot box. Later this fall, the grand daddy, Michael Moore, returns to longform documentary with Fahrenheit 11/9, his first since 2015’s lightly received Where to Invade Next. Fourteen years ago, when he released Fahrenheit 9/11, a voracious, apoplectic liberal audience (and likely a hate-watching counter-audience) inhaled the movie, making it far and away the most seen theatrical documentary film ever made. Fahrenheit 9/11 was dropped into a hostile, scary, routinely confounding political environment. Sound familiar?

Documentary has a fascinating power. It seeks the real and then distorts it with a camera, magnifying flaws and overwhelming circumstance. It is a conduit for unseeable or otherwise unknowable stories. It is, in the wrong hands, a tool for message-mongering and ham-fisted storytelling. But it can give us James Baldwin unvarnished. It can show beautiful horror. It can free the imprisoned. It can examine royalty. And it can detonate a family. It is indisputable that it is ever-present in our culture right now, a quest for truth unencumbered by artifice. And so it’s growing. How long it will last isn’t clear.

“I’ve felt many waves come and go. I have no illusions that it’s going to last in this golden era right now,” Neville says. “What I think has happened that I don’t think is going to un-happen is that, what I heard for a long time was, ‘I love documentaries. I don’t know where to see them.’ And now, if you go to iTunes or go to Netflix and see documentaries next to comedies, dramas, a lot of people pick documentaries. The accessibility has changed the profile of the films. Now, a lot of people—even a lot of people I know who work in scripted [programming]—say, ‘Well, personally, I watch documentaries. What I want to watch on a Friday night is a documentary.’”