Last weekend, during a press conference that preceded the round of 16 at Wimbledon, Serena Williams told reporters about an issue she runs into when she prepares for a match. It has nothing to do with the logistical challenges of babies or breastfeeding, although Williams had expanded upon both topics in another media session several days earlier, and had tweeted early that very morning about the sorrow of having missed the first steps of her 10-month-old daughter, Alexis Olympia Ohanian Jr. It also has little to do, directly, with Williams’s own tennis game. The issue involves her opponents — “these young ladies,” as the 36-year-old Williams put it — and the way they tend to elevate their play and abandon their inhibitions when they face her. “It’s interesting because I don’t even scout as much,” she said. “Because when I watch them play, it’s a totally different game than when they play me.”

To be the best you, have to beat the best, as they say, and for nearly 20 years now in women’s tennis, those last two words have been shorthand for Serena. She routinely fends off aspirants who lack her power or her strokes or her legacy but do have a significant advantage in one area: They are competing with little to lose. To be Williams is to simultaneously strike fear into, and embolden, her opponents. “It kind of backfires,” said Williams of her opponents in her July 7 press conference, “because everyone comes out and they play me so hard and now my level [of play] is so much higher because of it.”

On July 7, after the 23-year-old Madison Keys fell to Evgeniya Rodina in the round of 32, Keys attributed part of the loss to the fact that she’d let her mind wander, midmatch, to the idea of playing Williams next. She also reflected upon what it might be like to be Williams, the object of such fixation across all of women’s tennis. “It must suck every match,” Keys said, noting how hard it can be in practice to compete against someone who isn’t expected to beat you. “That’s what makes me great,” Williams said later that day when a reporter mentioned Keys’s comments. She sounded appreciative that someone had noticed. “I always play everyone at their greatest. So I have to be greater.”

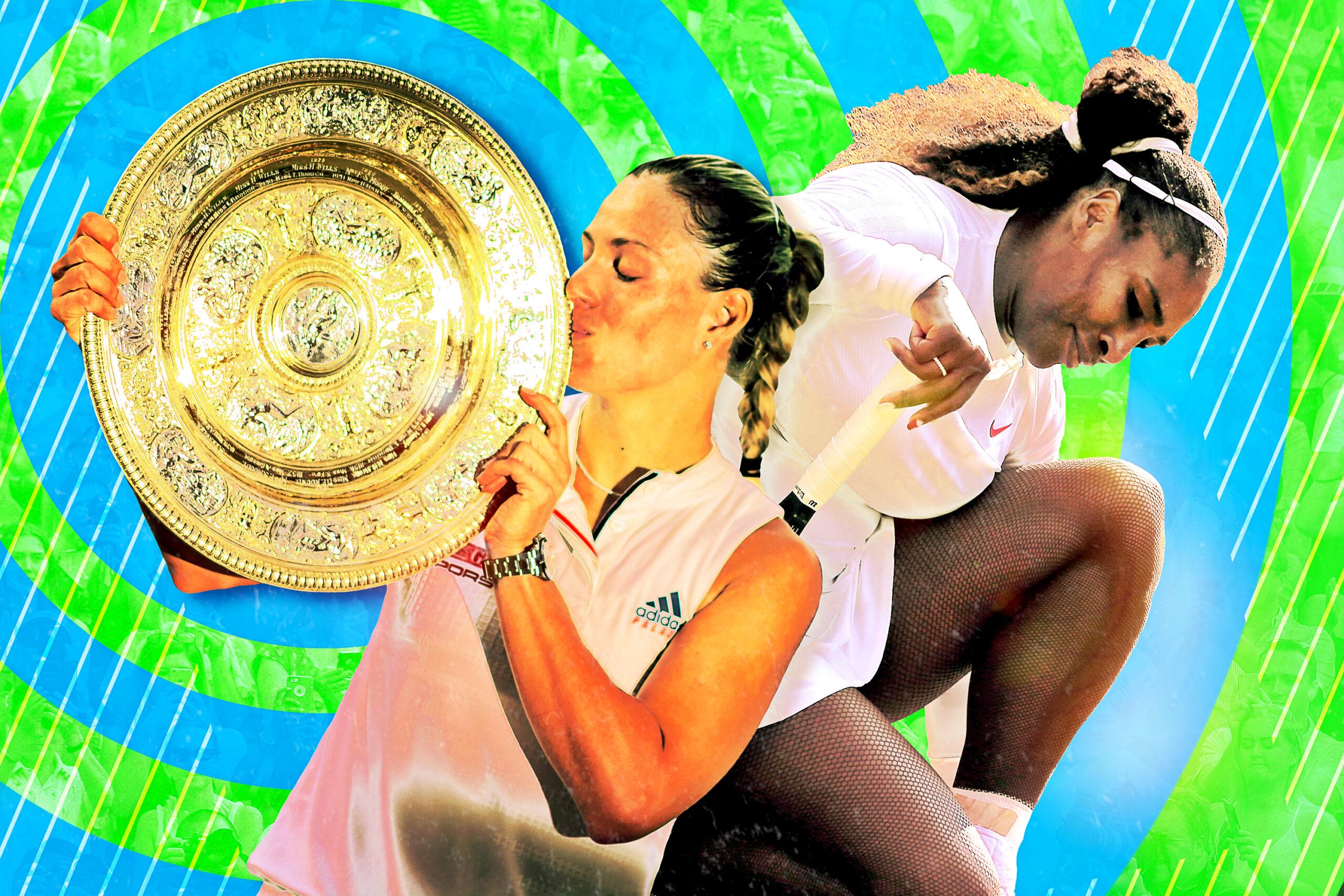

On Saturday, in Wimbledon’s championship game, this requirement proved to be just out of reach. Playing Angelique Kerber in a match that was delayed for two hours while Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic traded fifth-set serves in the men’s semifinal on Centre Court, Williams was unable to surpass or even equal the 30-year-old German’s confident consistency, falling 6-3, 6-3. Kerber broke Williams’s serve in the very first game and played patient, clean tennis throughout, calmly extending rallies (and sometimes ending them with her down-the-line forehand). Williams, meanwhile, hit more unforced errors (24) than she did winners (23) and at one point even did the unthinkable and double-faulted twice, back-to-back.

With her victory, Kerber made a personal comeback of her own, rebounding from a disastrous 2017 season in which she went 0-9 against top-20 players, was smoked in the first round of the U.S. Open, and fired her coach. She became just the second woman, the other being Venus Williams, to have defeated Serena more than once in a Grand Slam final. (Kerber won the 2016 Australian Open over Williams in three sets; Williams got her back a few months later in that year’s Wimbledon final.) And while she spoiled Williams’s bid to win Wimbledon less than a year after the 23-time Grand Slam singles winner gave birth and survived life-threatening postpartum complications, there’s a good chance Kerber ultimately did Williams a favor.

A Wimbledon victory on Saturday for Williams would have been like the 73-9 Golden State Warriors closing out the 2016 NBA Finals in five games, or the 2007 Patriots going 19-0 with a Super Bowl win. It would have been too perfect, too stunning, too broad and borderline-incomprehensible a caricature of success. (What’s worse, it definitely would have inspired people to opine that “women really can have it all!”) What happened instead serves to emphasize just how challenging Williams’s latest quest is, and it adds one more layer of intrigue and nuance to a career that has always been elevated by both.

“Tennis is unforgiving,” wrote Pat Cash, a former no. 4–ranked men’s tennis player from Australia, in the Times of London. “You can’t let it slide down the list of priorities, only to realise suddenly that playing the sport was what you wanted to do all along. Many have tried to turn back the clock, but nearly all have failed.” Cash wrote this piece — headlined “Williams is lost cause,” in January 2007 when Williams was in the midst of a career stretch during which she won just one major, the Australian Open, in a three-year period. “Deluded” is how Cash described Williams’s assertion that she could make her way back to the top of the sport. Since then, she has added 16 more Grand Slam singles titles, including one while pregnant with Olympia, despite missing nearly a year between 2010-2011 after cutting her foot on broken glass and suffering her first pulmonary embolism. But on top of that, she’s reached five additional major championship games — and lost.

Williams was uncharacteristically on her heels from the opening game of Saturday’s Wimbledon final; her balls seemed to have an unfortunate magnetic attraction to the net. Still, there was a string of points in the second set that provided familiar glimpses of the champion at her most effective. She began yelling at herself; she started visibly hurling her body into her shots. At 1-1 in the second, when Kerber ran up toward the net, Williams buzzed her with a ball, like a pitcher brushing back a batter. (The warning shot sailed long.) With the set tied at 2-2 and Williams down in the game 40 to love, she battled back to deuce; it felt like a pivotal moment, an epic comeback nested inside an even larger one. But Kerber won the next two points to hold serve, and Williams yelled out in frustration, and she would never get that close again. It was all a potential preview of what could well be the next phase of Williams’s career: one in which she digs out of jams rather than dominates, manages her playing time more like a starting pitcher than like a star shortstop, and adjusts the elements and tactics of her game like another athlete of similar caliber and longevity, the late-career LeBron James, who in recent years has incorporated a tweaked shot and a focus on energy conservation into his approach.

For someone who wins so often, Williams has gotten extremely good, over the years, at donning a semiconvincing mask of contentment and, no pun intended, serenity following a big loss. She gets this certain airy and overly polite tone to her voice; she appears to have instantaneously moved on to the next. But after yesterday’s match, this veneer could not hold. “It was such an amazing tournament for me,” she began in her typical brush-it-off manner, her smile looking pasted on. Then the glue failed, and her face fell, and her voice broke. “I was really happy to get this far,” she said, trying to reset her smile, as the crowd supportively roared. “For all the moms out there, I was playing for you today, and I tried. It’s obviously disappointing, but I can’t be disappointed.” For all of Williams’s future opponents out there — all those “young ladies” trying their hand against the first lady of tennis — there may not be a scarier, more aspirational thing to hear.