Like many members of MLB’s most recent free-agent class, Lorenzo Cain spent much of last winter waiting. As the 2017 playoff clubs brought back a historically high percentage of their preexisting players, habitual big spenders sought to stay under the luxury-tax threshold, rebuilders sat out the offseason, and data-driven front offices turned off the taps that once had flowed freely for past-their-prime players, potential suitors increasingly opted to develop and promote cost-controlled alternatives or wait until players’ demands came down rather than pay what teams once would have committed to the cream of the free-agent crop. “It’s definitely chilly out there,” Cain said about the bidding in January, amid concerns about collusion and even more credible fears that free agency might be broken.

In a market where teams looked for flaws in high-profile free agents, there were flaws to find in Cain. Although the center fielder’s above-average bat and elite speed and defense hadn’t yet shown any evidence of erosion, he was about to turn—and has since turned—32, an age that often inaugurates a period of steep decline for players generally and center fielders specifically. As Nate Silver once wrote about the aging of speed-dependent center fielders, “Once the speed goes—and speed evaporates more quickly than any other baseball skill—those guys become useless very quickly: They won’t have the range they once did, can’t do as much damage on the basepaths, and will see their batting averages drop as they can’t leg out as many base hits.” Cain roughly fit that profile: Although he’d incrementally raised his walk rate in three consecutive seasons after 2014, what appeared to be patience was largely a product of pitchers throwing him fewer strikes. Cain was never an especially selective hitter, nor a particularly powerful one, relying on BABIP and baserunning to generate much of his offensive value. He wasn’t an iron man, either: Last season was the first in which he’d played in more than 140 games.

Some prominent members of Cain’s free-agent cohort stayed unsigned deep into spring training, and some ended up inking for less than the qualifying offers they’d rejected. But Cain’s patience paid off: On January 25, he signed with the Brewers—the team that had drafted him in 2004 and promoted him to the majors in 2010 before trading him to the Royals in the Zack Greinke deal—for five years and $80 million, plus incentives and a no-trade clause. It was the longest and largest contract awarded to a 2017-18 free agent up to that point, as well as the richest free-agent deal in small-market Milwaukee’s franchise history. It was also more total money than most sources had expected Cain to receive.

For Cain, patience has kept paying off ever since. In a written statement at the time of the signing, Milwaukee general manager David Stearns cited Cain’s “speed, fielding prowess, and ability to hit for average” as the on-field benefits he would bring to the Brewers, and all of those skills are still intact: Cain has batted .291, stolen 16 bases, and recorded his highest Baserunning Runs, Defensive Runs Saved, and Ultimate Zone Rating totals since 2015 while tying for seventh among all outfielders in the Statcast-derived Outs Above Average. But he’s also done something different: dramatically reduced his chase rate and raised his walk rate, which has helped him post a career-high .394 on-base percentage and amass 3.4 WAR, a total that easily leads all NL outfielders. As the Brewers cling to a slight lead over the Cubs in the NL Central, they can credit their first-place status partly to Cain not only excelling in the same old ways, but also demonstrating a skill that he hadn’t flashed before.

Cain, who returns today from a groin strain that has sidelined him since June 23, has walked 43 times in 72 games. He’s only 11 walks short of his single-season high, which took him 155 games to set last season. His 13.8 percent walk rate ranks 16th among all qualified major league hitters, and his 21.1 percent chase rate ranks second in the NL, sandwiched between Andrew McCutchen and Ben Zobrist, two hitters who’ve always been stingy in swinging at pitches outside of the strike zone.

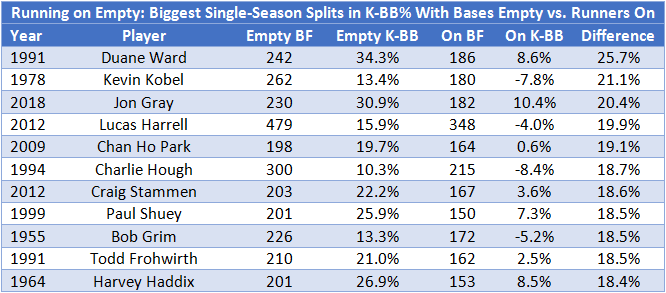

Cain’s chase rate last season was 31.7 percent, a full percentage point worse than the league average for non-pitchers. As of today, his chase-rate decrease relative to last season would be close to the largest in the pitch-tracking era (2008-18). The table below lists all year-to-year decreases of at least eight percentage points among hitters with a minimum of 300 plate appearances in both years.

It’s not unusual for hitters to lower their chase rates after making the majors, but most of that improvement tends to come at early ages. Sure enough, several of the previous players who took the largest leaps in selectivity were in their early to mid-20s, and Ramírez and Tabata were coming off their rookie years. By the time most hitters reach Cain’s age, they’re already at the point where their plate discipline has begun to regress. Of the players on the leaderboard above, only Pierzynski was older than Cain in his heightened-selectivity season.

Of course, Cain has always been a late bloomer by pro-player standards. Passed over by a high-school basketball coach and forbidden by his mother to play football, Cain took up baseball in his sophomore year, when he was so new to the sport that he had to borrow a glove to try out for the team. His history of playing catch-up may help explain how Cain has raised his game again at an age when time is supposed to start taking a toll. “What strikes me about Lorenzo is his ability to continue to grow as a player,” Stearns says via email. “He’s done it throughout his career. At a stage and at a point when a lot of players are content with who they are, Lorenzo is constantly trying to get better.”

Stearns doesn’t claim that his front office foresaw this sudden discipline gain, but the Brewers clearly were confident that they weren’t paying for past production when they reacquired Cain. “As we examined Lorenzo’s career arc this offseason, we thought that he was still improving as a player,” Stearns says. “It’s odd to say that about someone on this side of 30, but we thought that was the case. His plate discipline is really a product of his dedication to get better and his continued understanding of the game.”

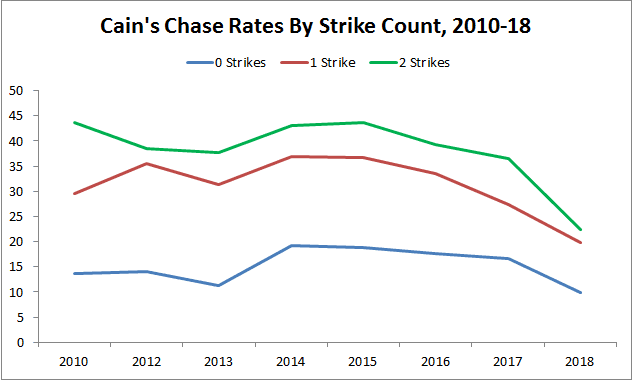

As FanGraphs’ Jeff Sullivan observed last month, much of Cain’s increased selectivity has come with two strikes. The chart below displays Cain’s chase rates in zero-strike counts, one-strike counts, and two-strike counts in each year of his career, with the “two-strike” line showing the steepest drop in 2018.

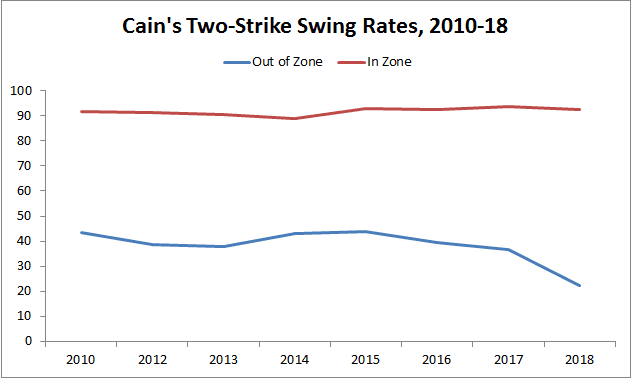

The most impressive aspect of Cain’s newfound two-strike selectivity is that it applies only to pitches outside the strike zone. He’s not swinging less often at all two-strike pitches; he’s just taking the should-be balls while continuing to offer at the presumptive strikes.

Thanks to that discerning eye, Cain has recorded career-best results with two strikes, hitting 67 percent better than the league when he’s one strike away from oblivion. Among hitters who’ve faced two-strike counts at least 100 times in 2018, Cain’s strikeout rate ranks in the 84th percentile, and his walk rate ranks in the 95th percentile.

Although Cain declined to comment on his altered approach at the plate, Brewers hitting coach Darnell Coles, who worked with Cain when Coles served as Milwaukee’s minor league hitting coordinator in 2010, is well-equipped to talk about how his past and present pupil has evolved in the several seasons since. When Cain was a rookie, Coles says by phone, “He was raw. You could always see he was wiry, he was strong, he had the ability to hit the ball from gap to gap.” That natural talent gave Cain a base to work with, but Coles notes that it took “some fine-tuning to get him to the point where he is.”

Cain’s improvement is partly mechanical: He’s refined his leg lift and load in a way that, according to Coles, entails “taking out some of the hang with his front side, because sometimes when he gets in his hitting position, he loads with his front leg. And sometimes it can get a little too high, so [it’s] managing that and getting it up and down in a position that he can recognize [pitches.]” Although this isn’t immediately apparent from afar—asked if the adjustment would be visible on video, Coles says, “I think it’s more subtle than that”—the hitting coach claims that much of Cain’s enhanced selectivity stems from “the consistency and timing of him getting in his hitting position on time so that he makes the best decision possible for that at-bat.”

Another factor that likely deserves some credit is where Cain has hit in the order. For the first time in his career, Cain has batted regularly in the leadoff slot, a decision that Brewers manager Craig Counsell has attributed to the team’s desire to get a good offensive player to the plate more often. This season, 59 of Cain’s 70 starts have come as a leadoff hitter, which makes up the majority of his 106 career starts in that spot.

Not every hitter would or should vary his plate approach based on his lineup position—as Counsell said in April, the Brewers “aren’t asking for anything different” from Cain depending on whether he bats first or third—and the last time he hit leadoff, in 2014, Cain walked only four times in 101 plate appearances. This year, though, he’s fully living up to his table-setting responsibilities. In April, Cain told Brewers beat writer Tom Haudricourt, “I’m just trying to be more of an on-base guy now than drive in runs,” and Counsell confirmed recently that Cain has “put this challenge on himself to be a guy who gets on base a lot.” Coles adds that in Cain’s new capacity as a veteran team leader, “he developed a knack for understanding each position that he hits in in the batting order and what that entails, and I think when he’s hitting first, he works counts a little bit more and tries to put the ball in play.” If batting leadoff has helped Cain focus on the count, that focus has evidently carried over to all of his offensive activity, because Cain has walked in a quarter of his 44 plate appearances elsewhere in the order.

Asked to comp Cain’s improvement to another hitter, Coles mentions Scooter Gennett, a Brewers draftee who’s found success in Cincinnati (and also appeared on the earlier list of plate-discipline improvers). In Cain’s case, Coles says, this season’s results represent “a total and complete understanding of [his] ability to put the ball in play, while not worrying about getting to two strikes. Because great [hitting]—and at this stage, he’s putting himself in position to be an elite hitter—is when you’re not afraid to get to two strikes while not missing your pitch early in the count. So there’s some selectivity that goes with that, [and] there’s some aggressiveness in the strike zone that you’re making sure that [pitchers] pay attention to.”

Cain’s new role and return to his rookie surroundings seem to have brought out the best in him as a hitter, and the Brewers are benefiting. Cain’s walks alone—to say nothing of the other offensive byproducts of being in better counts—have combined to increase Milwaukee’s win probability by 1.2 wins, and every win will be vital as they try to keep the Cubs at bay. Signing Cain may have required a record commitment for the franchise, but he’s been a bargain so far. And when his speed and defense do decline, the newly selective star will still have a skill to fall back on.

All stats updated through Friday’s games.