On Saturday, the Colorado Rockies demoted either one of the best or one of the worst pitchers in baseball to Triple-A. Jon Gray, the team’s 26-year-old strikeout artist, was the Rockies’ Opening Day starter for the second consecutive year, and while he’s not the first Opening Day starter to be optioned since then—Oakland’s Kendall Graveman beat him to the Pacific Coast League by more than two months—the newest member of the Albuquerque Isotopes is the most perplexing pitcher of 2018.

Although the Rockies aren’t known for developing pitchers, Gray has seemingly been bound for acehood since the franchise selected him with the third overall pick of the 2013 draft. For three springs in a row, he ranked among the best pitching prospects in the game, and by some metrics, he’s been one of the best pitchers in the majors since the day he debuted. Among pitchers with at least 400 innings since the start of 2015, Gray’s park-adjusted FIP ranks 12th (as does his per-pitch slider value), placing him in the company of past and present Cy Young candidates.

After posting the most valuable season by a rookie pitcher in Rockies franchise history in 2016, Gray got even better last year. The 6-foot-4 flamethrower, whose fastball sits at 96 and spikes close to triple digits, was one of the biggest reasons for the Rockies’ skin-of-their-teeth postseason appearance, leading Colorado pitchers in FanGraphs WAR despite amassing only 110 1/3 innings, most of which came after his late-June return from an April foot fracture.

Gray, who ranked fifth in FanGraphs WAR among major league pitchers from August 1 on, was arguably the most effective starter ever to pitch for the franchise last season, and he seemed to have cracked the Coors Field code: When he pitched at altitude, where breaking balls tend to be flatter, he threw more fastballs and got more grounders, and when he pitched on the road, he relied more often on breaking balls and missed more bats. When the Rockies needed to win one wild-card game against the Diamondbacks to advance to the NLDS, Gray got the start opposite Zack Greinke, whom he’d outpitched down the stretch. He lasted only four outs, allowing seven hits and four runs in the losing effort, but he remained one of the majors’ most promising pitchers entering 2018.

According to some stats, Gray has fulfilled his promise. Pick a pitching metric other than ERA—FIP, cFIP, xFIP, DRA, SIERA—and Gray appears to have improved relative to last season: Most notably, the righty has raised his already robust strikeout rate by almost five percentage points, and no starter with at least 50 innings pitched in both 2017 and 2018 has allowed a lower contact rate relative to last year. On the other hand, he has a 5.77 ERA, which is ugly even after adjusting for calling Coors Field home. (Gray’s ERA this season is slightly higher on the road.) Only eight qualified pitchers this season have a superior park-adjusted FIP, but only seven have a higher park-adjusted ERA. Or, to express the same strange dichotomy in different terms, Gray has the 13th-best FIP-based WAR of any pitcher and the 12th-worst win probability added. There’s no precedent for a pitcher simultaneously seeming so terrific and so terrible.

As one would expect given Gray’s two-faced stats, his demotion produced strongly conflicting responses. Some fed-up fans welcomed the news, no doubt sick of seeing opponents post crooked numbers against the erstwhile ace: In his last nine starts (only four of which came at Coors), Gray recorded a 7.35 ERA. Many statheads, meanwhile, mocked or questioned the move, citing Gray’s advanced stats as evidence that he didn’t deserve to be banished.

Normally, it makes sense to side with the statheads when a pitcher’s traditional and fielding-independent pitching stats don’t tell the same story. In most cases, a pitcher’s past ERA is a poor indicator of his future ERA, whether within the same season or across multiple seasons; any advanced stat that estimates how many runs a pitcher “should” have allowed will more accurately predict the rate at which he will allow runs going forward.

From afar, Gray looks like a candidate to be saved by sample size. One of Gray’s biggest bugaboos this year has been his tendency to allow hits on balls in play: His .386 BABIP this season leads all pitchers with at least 40 innings pitched. Granted, Gray’s surroundings have something to do with that: Thanks to its biggest-in-baseball outfield, Coors increases other hit types by roughly as much or more than it does home runs, and the Rockies’ outfield defense hasn’t helped. Even after park adjustments, Gray’s BABIP alone has cost the Rockies almost two wins, by far the worst margin in the majors. But because most pitchers’ BABIPs tend to converge toward the league average over time, Gray’s current inflated figure ought to be encouraging: A mile-high BABIP is often a sign that an ERA reversal is coming. Most high-BABIP pitchers don’t need a trip to Triple-A to fix the problem; they just have to point toward their FIPs, chant “regression” three times, and wait for the correction to come.

In 2018, every front office knows this—even the one that’s spending $52.5 million this season on Ian Desmond, Wade Davis, Bryan Shaw, and Jake McGee (combined 2018 Baseball-Reference WAR total: -2.2). Dig deeper, though, and Gray’s season sinks into a, well, gray area, where the remedy may be more complicated than waiting for batted-ball justice to prevail. Gray’s struggles this season have gone beyond BABIP. There’s only one way for a pitcher to post such sterling fancy stats while also allowing so many runs: He has to concentrate his crappiness at the most inopportune times. Gray has definitely done that.

“It’s fascinating, really,” Rockies broadcaster (and former outfielder) Ryan Spilborghs says by phone. “His numbers are elite, but he runs into trouble all the time.”

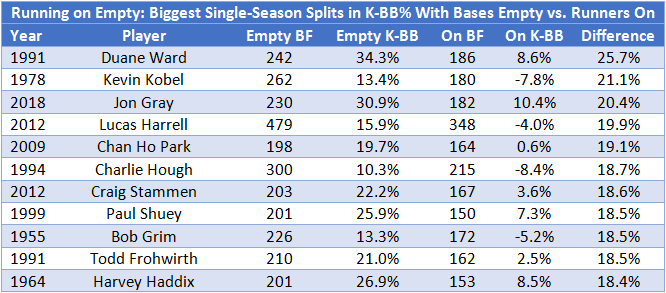

Gray’s BABIP has been higher with the bases empty than with runners on (.405 vs. .367). But he’s been much, much better at racking up strikeouts and avoiding walks when no one is on base. With the bases empty, Gray has recorded a 30.9 K-BB rate—almost identical to Max Scherzer’s major league-leading overall rate—even though Coors is the majors’ most strikeout-averse park (as well as one of the most walk-prone). With men on, though, his K rate has dropped precipitously, his walk rate has doubled, and his K-BB rate has plummeted to 10.4, which would be below the overall MLB baseline for starters.

Even after accounting for the fact that inferior pitchers work with men on base often, pitchers tend to have slightly lower K-BB rates with runners on. But the difference between Gray’s rates this season is eight times as large as the average split for starters with at least 50 total innings pitched. In fact, the raw difference between Gray’s bases-empty and runners-on K-BB rates would be the third-largest single season split ever for a pitcher with at least 150 batters faced in each situation.

Those splits jibe with what Rockies manager Bud Black told reporters about the Rockies’ decision to demote Gray. “When there have been some baserunners, when there have been some crisis points in a game, we’ve seen some inconsistency in his ability to work through that trouble,” said Black, who also asserted that the starter’s struggles are more mental than mechanical and questioned Gray’s “confidence to make pitches.”

It’s both vaguely reassuring and even more mystifying that this problem didn’t plague Gray last year, when his K-BB rate was slightly higher with runners on. With some pitchers, a sudden, drastic difference in performance with men on and bases empty might indicate mechanical inconsistency stemming from switching between the windup and the stretch. But video review (and a direct message from MLB.com Rockies beat writer Thomas Harding) confirms that Gray hasn’t significantly altered his standard stretch-like delivery in either scenario. Nor has Gray’s pitch selection this season been dramatically different with men on: He’s thrown the fastball a bit less (49.0 percent vs. 52.6 percent) and the slider somewhat more (37.2 percent vs. 28.6 percent), not an unexpected pitching pattern in a situation where minimizing contact matters more than usual.

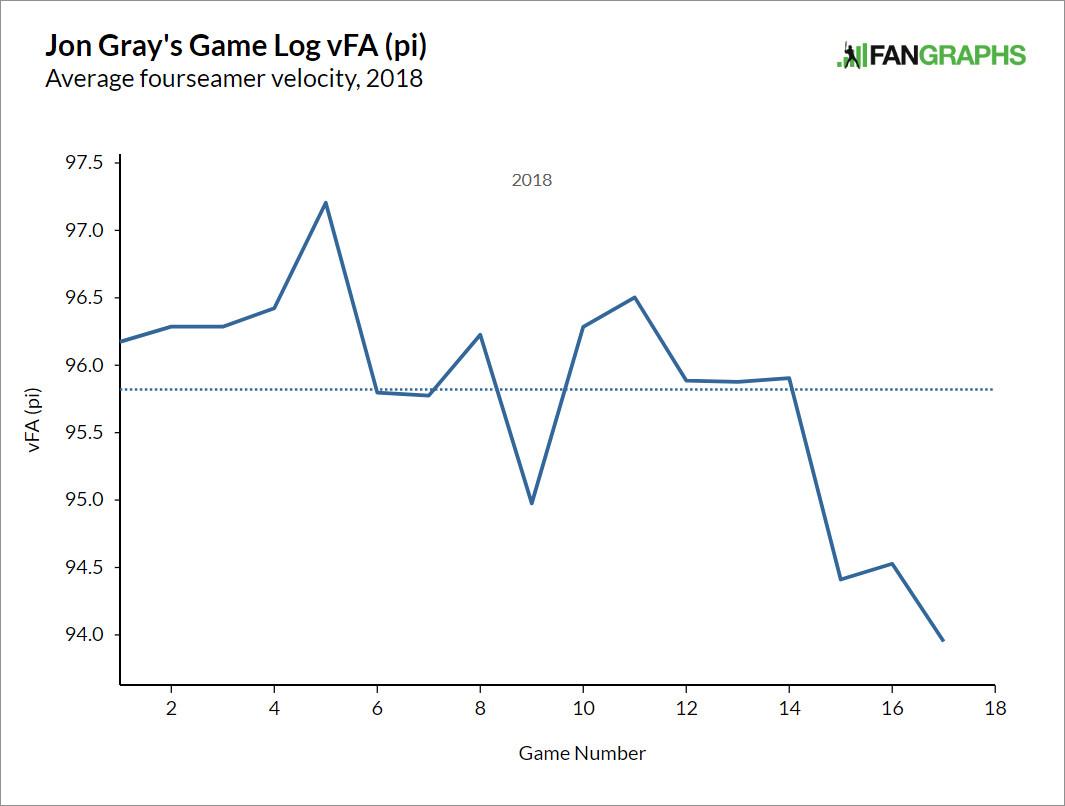

Some have suggested that the difference between Gray’s fastball and breaking-ball vertical release points might be tipping hitters off to what’s on the way, but that hypothesis doesn’t hold water. While it’s true that Gray’s fastball-breaking-ball separation is tied for 29th-largest among the 287 pitchers who’ve thrown at least 500 total pitches this season (and had both fastballs and breaking balls classified by Statcast), that’s not necessarily an obstacle to success: Scherzer, Justin Verlander, Luis Severino, and Josh Hader have bigger gaps. Moreover, Gray’s separation is almost the same with the bases empty as it is with runners on, so it wouldn’t explain his Jekyll-and-Hyde-style splits. Like most pitchers, he also throws harder with runners on base, although his overall average fastball speed has fallen roughly two ticks in his past three starts, another cause for concern.

The most likely culprit behind Gray’s puzzling season, beyond being snakebit, is a lack of command. “He misses middle and up all the time,” Spilborghs said, continuing, “You miss middle-middle to major-league hitters, that BABIP is not misleading.”

According to Hardball Times analyst Bill Petti’s “Heart%” and “Edge%” metrics, Gray has located pitches in the center of the strike zone and outside the strike zone more often—and on its edges less often—than he did last season or than the typical pitcher has in 2018, and his rating according to Baseball Prospectus’s “Command” metric, which grades pitchers’ ability to place pitches in favorable spots, has declined from 60 on the 0-100 scale last season to 49 this year. In other words, he’s been more likely both to miss by a lot and to serve up meatballs.

BP’s “called-strike probability” numbers back that up: Gray’s percentage of pitches with a one percent or lower chance to be called a strike has risen from 20 percent last season to 25.9 percent this year, and his percentage of centered pitches with a 99 percent or greater chance to be called a strike has also increased from 10 percent to 15.6 percent. As a result, although he may be allowing less contact, when the contact has come, his barrel rate, hard-hit rate, and average exit speed have all surpassed last season’s. Oddly, though, while Gray does seem to have missed up more often with men on than he has with the bases empty, he hasn’t thrown those one percent or 99 percent pitches at a greater rate with runners on. The fat slider he gifted to Brandon Belt with a man on second in his most recent start was merely a 98.5-percent probability strike.

Even if shaky command can explain some of Gray’s hittability, much of the “why” would still be a mystery. Spilborghs, like Black, looks to Gray’s gray matter. Sometimes lousy luck can lead to a player being blamed unfairly, but even Gray has acknowledged having a miscalibrated mentality at times. “He’ll come back and postgame he’ll say ... ‘I just wasn’t throwing competitive pitches.’ And you’re curious, because you’re going, ‘How is that possible? What is going on that you can’t maintain focus for this amount of time?’” Spilborghs speculates that Gray might one day move to the bullpen and find it to be a better fit, like the Diamondbacks’ Archie Bradley before him. “The second he said ‘I lose focus,’ I’m like, ‘Dude, he’s a two-inning guy,’” Spilborghs says. “Make him a high-leverage, two-inning guy, take the thought process out of it for him.”

The Rockies still hope to harness Gray’s stuff and salvage what seemed to be a bright future as a starter. If Gray responds positively to this “reset,” the relatively low-pressure (if not low-altitude) interlude in Albuquerque may help the sabermetric cipher learn to “settle [him]self in the heat of the battle,” as Spilborghs puts it. Until then, though, there’s a chance that the models that predict most pitchers’ performance may not work as well for him. “This is where stats meet human interest,” Spilborghs says.

For now, Gray has the highest career BABIP in modern major league history for a pitcher with at least 400 innings pitched, as well as the most gigantic gap between his ERA and FIP. Both of those extremes should regress, just as the stats suggest. But regression isn’t always purely the product of a player’s luck changing. Sometimes it’s also a matter of making a change. Not every athlete can do that, which is why most bullpens are well stocked with former starters. But if the Rockies righty can learn to be the good Gray all the time, his ceiling is still sky-high. “It reminds me a lot of Cliff Lee or Roy Halladay,” Spilborghs says. “Don’t forget, those guys got sent down to the minor leagues and came back better.”

All stats updated through Saturday’s games. Thanks to Dan Hirsch of The Baseball Gauge and Bill Petti of The Hardball Times for research assistance.