No matter how many mocks the internet churns out, the NFL draft’s first round remains unpredictable. Just about every year, we see trades, shocking player reaches, and surprising prospect falls collaborate to blow up any expectations about how the round will go. But while story lines constantly change and forecasting specific team-player pairings is always a crapshoot, the first round does tend to adhere to two general big-picture patterns: First, you can typically expect that two to four quarterbacks will get selected—that’s been true every year but one since 2002—and second, that a majority of the rest of the picks in the opening round will go toward one of the sport’s other four premium positions: edge rusher, offensive tackle, receiver, and cornerback.

This year, though, may not conform to those rules. Because of a combination of factors—some random and some due to the evolution of the sport—the anatomy of April 26’s first round could be wildly different than the norm.

The Quarterback Gold Rush

The most obvious outlier to the standard structure of the first round is what’s shaping up to be a historic early run at the quarterback position. With a week to go until the draft, it feels like it’s all but a lock that five passers—USC’s Sam Darnold, UCLA’s Josh Rosen, Wyoming’s Josh Allen, Oklahoma’s Baker Mayfield, and Louisville’s Lamar Jackson—will come off the board in the first round. That would be the new high mark for the first round since 1999, a draft in which Tim Couch, Donovan McNabb, and Akili Smith went one-two-three, with Daunte Culpepper (11th overall) and Cade McNown (12th) not far behind. This year might be even more top-heavy, and it’s not hard to imagine scenarios where four—perhaps even five—quarterbacks are picked inside the top 10.

So why is this year so different? It’s partly just the randomness of the draft; this year there is a higher number of outstanding quarterback prospects. But there could be a few other factors that have driven up demand and thus pushed this year’s signal-callers up draft boards. Teams have started to catch on to the idea that the best way to build a Super Bowl winner centers around finding a good (maybe not even great), cheap rookie-contract quarterback, then taking advantage of those four or five cost-controlled years to spend lavishly in free agency to build a championship roster. That new model for team-building could push a handful of middling squads (especially those with GMs or coaches who think they’re on a short leash) to adopt a more aggressive draft strategy when it comes to the quarterback position.

Another potential factor that could affect this year’s first round is the relative lack of talent in next year’s QB crop.

That bleak early outlook for 2019 means that in addition to the obvious quarterback-needy teams, there may be a handful of other franchises (that are still a few years away from needing a change at the position) that could be motivated to take a signal-caller early in the draft. Consider: Philip Rivers is 36 and has two years left on his deal; Ben Roethlisberger is 36 and has toyed with retirement; Drew Brees is 39 and on a two-year deal; and Tom Brady is 40. In any other year, the Chargers, Steelers, Saints, and Patriots would probably lean toward adding instant impact players at positions of immediate need. But a weak 2019 quarterback class could accelerate their investment plans at QB.

Put it all together and it’s not too wild to think that Oklahoma State’s Mason Rudolph could sneak into the back half of the first round. Rudolph is considered a second-tier passer in this class, but he’s got plenty of the traits teams look for in a franchise quarterback: size (6-foot-5, 235 pounds), a decent arm, the ability to attack downfield, and the poise to play from the pocket. If the former Cowboys star does end up as the sixth quarterback chosen in the first round, it’d tie an all-time NFL record set back in 1983—the legendary draft class that included three future Hall of Famers in John Elway, Jim Kelly, and Dan Marino.

The Premium Position Conundrum

The glut of top-tier passers isn’t the only thing that’s abnormal about the composition of this year’s draft class. It has the exact opposite problem at a few of the sport’s other premium position groups.

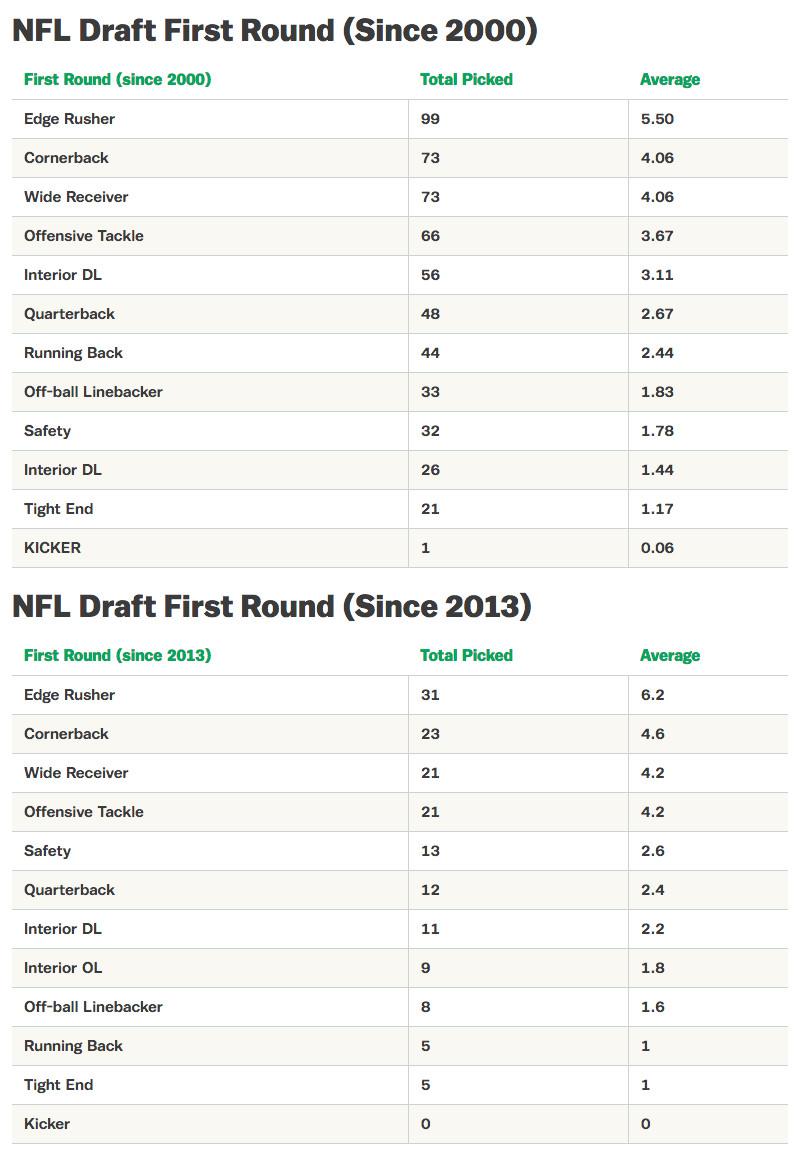

The NFL is a passing league, and the way in which teams approach the draft reflects that. Going back to 2000, 126 of 180 total top-10 picks (70 percent) have been used on five positions—quarterback, receiver, offensive tackle, corner, and edge rusher—all of which, uncoincidentally, revolve around either passing or stopping the pass. (Note: There is obviously some subjectivity in differentiating edge rushers from interior defensive linemen or off-ball linebackers, but I did my best to designate based on the way these players were viewed coming into the draft.) And with rules continually changing in favor of increased passing and scoring, franchises have ramped up their focus on those five groups. If you narrow the scope to the past five years, those five premium positions account for 80 percent (40 out of 50) of top-10 picks.

That trend continues outside the top-10 picks:

This year may buck the trend, even with a mad scramble on quarterbacks. This class is deep at corner, yes, but it’s short on top-tier players at the three other most valuable spots. The only consensus first-rounder at receiver is Alabama’s Calvin Ridley, but he’s anything but a lock for the top 10. SMU’s Courtland Sutton is getting some first-round buzz, as is Maryland’s D.J. Moore, but Sutton’s still inconsistent and raw, and despite a strong combine showing that has Moore shooting up into the first round in more than a few mock drafts, he did get a “go-back-to-school” grade from the league’s Draft Advisory Board, so there’s no telling where he’ll end up.

The edge rusher group appears to be shallow at the top, too. NC State defensive end Bradley Chubb is the obvious headliner, and is projected to come off the board in the top-5. But past Chubb, there are just two first-round locks—Boston College pass rusher Harold Landry and UTSA edge player Marcus Davenport—and both of them are projected most frequently to come off the board somewhere in the teens (though Landry’s gotten some top-10 buzz over the past few weeks). At offensive tackle, things are even more grim: Notre Dame’s Mike McGlinchey is the consensus best prospect in the class, but it’d be a shock if he broke into the top 10, and college tackles Connor Williams (Texas) and Isaiah Wynn (Georgia) are both projected to play at guard at the next level.

Put more simply, this draft should present an interesting litmus test for which teams subscribe to a Best Player Available model that largely ignores traditional positional values. The shortage of top-shelf talent at edge rusher, tackle, and receiver could create two scenarios. The first: Teams reach, and reach badly, in order to secure players at those spots, thus pushing more complete or more talented prospects at non-premium positions down the board. The second: We might see an unusually high number of those non-premium positions come off the board early in the first round. It depends on how the chips fall at QB, but elite prospects like running back Saquon Barkley and guard Quenton Nelson are both almost sure to go top-10; safety Derwin James and nickel corner Minkah Fitzpatrick could both go that early; defensive tackle Vita Vea could break into that range; and we might even see off-ball linebackers Roquan Smith and Tremaine Edmunds crack the single digits.

Are Non-Premium Positions Catching Up?

For some teams, it may be worth gambling on less talented or less game-ready prospects at premium positions because that player may fill an immediate need, represent the potential for a bigger impact on the field, or provide the opportunity for an immense short-term advantage in the form of cap space—just compare rookie contract numbers with those for the league’s best players at those positions. But that doesn’t mean that selecting a top-tier player at one of the historically lower-value positions like interior defensive line, center, tight end, off-ball linebacker, and yes, running back, is necessarily a bad choice. The NFL is changing, and as passing continues to increase and traditional positional roles evolve, some of those lower-tier position groups have closed the gap in their on-field value.

The devaluation of the running back position is well-documented, particularly when it comes to what those players are getting on the current free-agent market. As Ringer colleague Rodger Sherman notes, free-agent running backs get paid less than kickers, and, on average, it’s the third-lowest-paid position in the NFL, ahead of only long snappers and fullbacks. Yet Barkley could go as high as no. 2 to the Giants, and it’d be a mild surprise if he falls past Tampa Bay at no. 7—a draft slot that could signal the continuation of a mini-trend: Over the last two years, three running backs have come off the board inside the top-10 (Ezekiel Elliott in 2016, and Leonard Fournette and Christian McCaffrey in 2017). Last year NFL squads spent more draft capital on running backs than in any other draft since 2008, with 30 players at that position selected overall (the most since 1996).

Part of the reason for that sudden increase in investment at the position may be that teams favor spending draft capital on younger, more explosive, and healthier backs over using cap space on older, more worn-down backs in free agency. But more importantly, running backs are becoming a more integrated and essential part of NFL passing attacks. Passing is much more efficient than running, and, as Sherman explains, Barkley’s elite skills as a route runner and pass catcher make the strongest argument for why he’s worth such an early pick.

Defenses must account for those mismatch-creating running backs out of the backfield, so off-ball linebackers with sideline-to-sideline speed to cover them will become increasingly important. In the last 18 drafts, an average of just 1.8 non-rush linebackers have been chosen in the first round, and the last time more than three were taken in the opening round was 2006. This year, both Smith and Edmunds could go in the top 10, and Boise State’s Leighton Vander Esch and Alabama’s Rashaan Evans could join them as day-one picks. But it’s not their run-defending chops that teams are looking at with these four linebackers—it’s their range, instincts, and playmaking skills in coverage, especially against versatile pass-catching tight ends and running backs, that could make them worth a valuable first-round pick.

The same logic applies in projecting both Florida State safety Derwin James and Alabama defensive back Minkah Fitzpatrick as worthy of top-10 selections. Teams have picked just three safeties inside the top-10 in the past 10 years, and with Mark Barron’s (seventh overall in 2012) position switch to linebacker, there are really only two top-10 picks playing safety in the NFL right now: Eric Berry and Jamal Adams. And, while outside corners are highly valued, both in the draft and per the going rates in free agency, nickel cornerbacks have yet to catch up to their outside-the-hashes brethren in the money department. Perhaps that’s because slot cornerbacks are still technically part-time players, but with the explosion in three-receiver sets in the NFL over the past few years, their role has never been more important. For both James and Fitzpatrick, the positional-group pecking order hasn’t caught up to the modern game: Middle-of-the-field defenders who can run with slot receivers, tight ends, and running backs or come in on occasional blitzes provide tremendous value to their teams.

The positional value paradigm shift can already been seen in the interior of the offensive line, though, and that’s what makes taking Nelson anywhere in the top-10 a no-brainer. Teams may still be reticent to take guards that high, and in the last 10 years, it’s happened just three times (Brandon Scherff, Jonathan Cooper, and Chance Warmack), but interior linemen have narrowed the pay gap on the tackle position. Seven guards average north of $10 million per year—there’s 13 at tackle—and Andrew Norwell just signed a five-year, $66.5 million deal with the Jaguars at an average of $13.3 million per year. That is tackle money. So why are interior linemen getting paid nearly as much as the blind-side protectors? Well, it’s to block the influx of highly explosive, penetrating interior defensive linemen. Defensive tackles are no longer big, slow, run-pluggers, they’re like Aaron Donald and Fletcher Cox: game-plan-wrecking pass rushers from the inside. And that’s why guys like Vea, or Michigan’s Maurice Hurst, could come off the board early on.

The first round of the 2018 NFL draft may look different than any first round in recent memory. But it may not be just an aberration; it could be a representation of how the sport is evolving, and how the league’s positional paradigms are slowly changing. Running backs are receivers. Defensive linemen play every spot on the line. Defensive backs can line up all over the field. As we trend toward positionless football, it muddles the established hierarchy of positional value.