It’s impossible to discuss José Bautista’s legacy without mentioning the bat flip, so let’s start there.

It’s too soon to know exactly how contemporary baseball moments will be remembered decades in the future, but it’s easy to imagine that Bautista’s postseason bat flip will become the single lasting, defining memory of the 2015 season. The setup to that moment—which involved Toronto overcoming an 0-2 series deficit against Texas in the ALDS and a Game 5 that featured the wildest inning in recent baseball memory—was necessary to amplify its emotional impact, but really, all future generations will need to know is entirely contained in that 42-second video.

Rangers catcher Chris Gimenez set up low and outside. Pitcher Sam Dyson missed belt-high and in. Before the announcer even finished giving the count—“the 1-1 from Dyson”—the crowd exploded in a sheer, primal wall of noise. The Rogers Centre home run horn blared; Marcus Stroman leaped with joy; Bautista, having just bashed the most important home run of his career in his most important at-bat, jogged calmly around the bases.

Except, the replay showed, he wasn’t so serene.

That bat flip—or perhaps it’s better described as a bat throw, or a bat toss, or a violent, menacing, triumphant bat heave—occurred two and a half years ago this week, in which time Bautista faded from feared MVP candidate to perpetually slumping veteran to free agent in need of an offer. His MLB career might be over. The 2018 season is 11 days old now, and he is nowhere to be found: not in an MLB lineup, not on a bench, not even staying active with minor league at-bats. MLB Trade Rumors’ latest update on the 37-year-old slugger came on March 26, when multiple reporters debunked a rumor that the Rays and Braves were interested in signing him; the site’s last update before then came on March 8, when a report hinted at possible retirement for the former Toronto star.

Whether or not he plays again, Bautista’s foremost legacy will always be him launching a ball into the seats and his bat across the grass in tandem. But the flip itself exists at the intersection of two broader trends that defined the career of the man beyond the meme, and which are helping to define baseball’s evolution in the late-2010s.

The first involves the act of the flip itself, which was both subsumed under and the clearest manifestation of Bautista’s divisive persona. He was loud and brash and full of personality in a sport that often asks even its best players to hew to on-field blandness, and he engendered his share of feuds, leading to a range of responses from coded racism from a rival front office to literal on-field violence from a player whose team he had bested with that monumental 2015 home run.

Bautista, though, saw what his critics labeled as antics as, instead, a cultural byproduct, born from years playing baseball in the Dominican Republic, where players and fans are “loud” and “emotional” and “always singing and dancing,” he said in The Players’ Tribune a month after flipping his bat.

“There was no script,” he said of that moment. “I didn’t plan it. It just happened. I flipped my bat. It wasn’t out of contempt for the pitcher. It wasn’t because I don’t respect the unwritten rules of the game. I was caught up in the emotion of the moment. … Those moments are spontaneous. They’re human. And they’re a whole lot of fun.”

Even just a couple of seasons later, it seems as if more viewers agree that emotions are a whole lot of fun. The 2017 World Baseball Classic featured vibrant celebrations at every turn, with nowhere near the controversy that Bautista instigated, and in last year’s World Series, Carlos Correa actually stopped running around the bases to unleash a frenzied fist pump following a home run. Nobody took any umbrage at his spontaneous display.

The second trend for which Bautista was a foundational member is the air-ball revolution, or the swing-change revolution, which has dominated baseball discourse over the past few seasons as one of the contributing factors behind the home run boom. Bautista needed to change his swing to become a valuable MLB player, and he did so in 2010, before that was the du jour step for a struggling hitter.

A 20th-round pick out of Chipola College in the 2000 draft, he was never more than organizational filler as a prospect: From December 2003 through July 2004, he was shuffled in the Rule 5 draft, lost on waivers, sold, and traded twice on the same day. Multiple last-place teams saw little reason to play the 23-year-old, and for good reason—Bautista struck out 40 times in 96 MLB plate appearances that season and didn’t homer once. He didn’t homer in 2005, either, and was somehow even worse in his big league cup of coffee that year. Through two seasons and 127 plate appearances, he posted a 27 OPS+, and he was a woeful defensive third baseman besides.

With some improvement at the plate, Bautista settled into a regular role in Pittsburgh for the next few seasons, albeit still as a below-average hitter and sub-replacement player overall. But in August 2008, he lost his job to the lesser LaRoche and went to Toronto in a trade for a player to be named later.

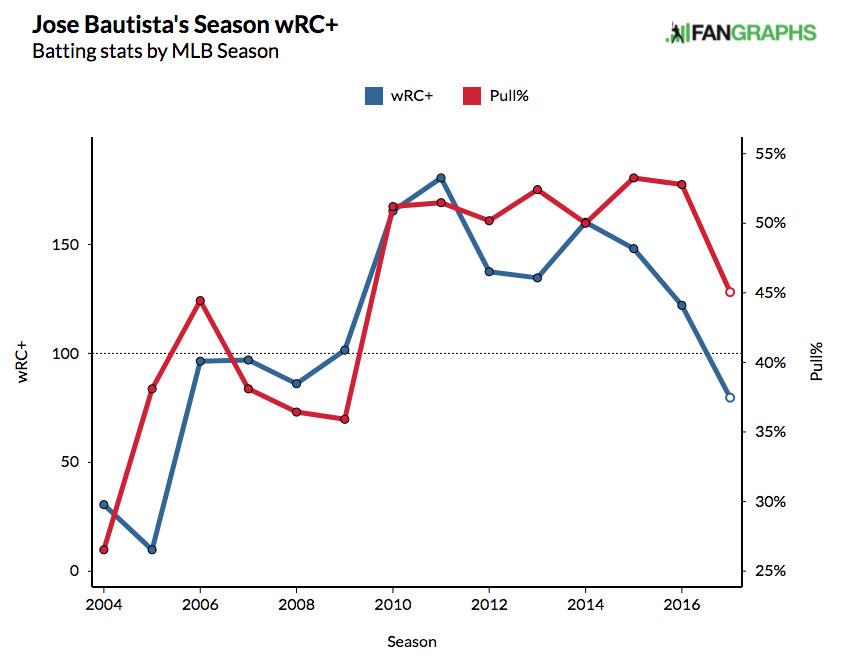

Then he moved predominantly to the outfield, altered his swing, and transformed into an entirely new player. Working with Toronto hitting coach Dwayne Murphy, Bautista shortened his swing to bring his bat more directly through the strike zone; along with this change came increases in balls hit hard, balls hit in the air, and balls hit toward the pull side—in other words, contact with a much better chance of going for extra bases. Bautista optimized his latent power, and his production rose accordingly.

In 2010, he hit 54 homers when nobody else hit more than 42, giving him the highest single-season total between Alex Rodriguez in 2007 and Giancarlo Stanton in 2017. In 2011, he led in home runs again while eclipsing a 1.000 OPS. Before changing his swing, Bautista had never appeared on an awards ballot of any kind; afterward, he placed in the top four of the AL MVP vote in consecutive years and reached the All-Star Game six years in a row.

More broadly, Bautista’s ascendance represented a historical anomaly. From 2004 through 2008, he was worth negative-2.9 wins above replacement; in modern MLB history, only 26 other players have been so bad in at least 1,000 plate appearances through their age-27 season. Those players then averaged a total of 0.3 cumulative WAR at age 28 and beyond. (Take out David Segui’s 13.6—the only mark above 3—and the group’s average becomes negative.)

In his age-28 season, though, Bautista was worth 2.9 wins in Toronto, and from 2010 through 2015, he was worth 34.8 more WAR, making him a top-10 position player in all of baseball in that span. Put another way, after he was one of the 30 worst regular position players in MLB history through age 27, he was one of the 30 best position players in MLB history from ages 29-34.

Until he posted a negative number last year, Bautista ranked first among all Blue Jays position players in career WAR. (Now he places second, trailing Tony Fernández by just half a win.) He also was the face of the most fun and successful Toronto teams of the past quarter-century, with that 2015 bat flip as the highlight not only of his own career but of the Blue Jays franchise since Joe Carter touched ’em all in 1993.

As a centerpiece of a fearsome offense that also featured Josh Donaldson and Edwin Encarnación and led the majors in scoring by 127 runs, Bautista received more MVP votes in 2015. Then the downturn came, and quickly—he saw his OPS drop by nearly 100 points in a diminished, if still somewhat productive, 2016 campaign in which Toronto made its second consecutive ALCS. His production cratered in 2017, and Toronto’s only logical move was not to exercise his mutual option for 2018.

He still homered 23 times last season, but every underlying statistic trended in the wrong direction. His strikeout percentage ballooned to its highest rate since 2004. His walk rate hit its lowest point since 2008. His isolated power dropped to its lowest since 2007. His home run per fly ball rate fell; his hard-hit rate collapsed; his swinging strike rate crept too high, as he swung at his highest frequency in nearly a decade but whiffed more often than ever before. After the All-Star break, he hit .165/.256/.326 in 69 games.

In the field, the aging Bautista exhibited abysmal range, ranking in the bottom 10 among 206 outfielders who qualified for Statcast’s outs above average leaderboard, and on the bases, he was about as fast as Miguel Cabrera, with a similar propensity for grounding into double plays. Moreover, his power advantage is diluted in a league environment where nearly everyone has power, as the league’s record-setting home run pace has most severely affected the middle class. Players with little pop in the past can now blast a home run every week, which doesn’t let the obvious power threats like Bautista stand out; 116 other players reached 20 home runs last year, and many of them can also field or run or—most crucially—give a team multiple cost-controlled seasons and a real hope for improvement.

Bautista is a DH-only player in a scarce market for DH-only types: Besides Tampa Bay and maybe Kansas City, every AL club has an entrenched designated hitter or DH rotation, either because that’s where a slugger fits best (e.g., J.D. Martinez in Boston) or because the team is already rostering a faded veteran and has nowhere else to put him (e.g., Victor Martinez in Detroit).

His absence from a 2018 roster is the natural result of both his 2017 performance and the emerging trend of teams no longer paying for veterans or one-dimensional power bats. He’s not the the only poor-fielding, power-hitting veteran still struggling to find a job. The likes of Matt Holliday, Andre Ethier, Seth Smith, and Brandon Moss are all still unemployed, too. Jayson Werth settled for a minor league deal with the Mariners. Mike Napoli’s playing for Cleveland’s Triple-A team. Adam Lind played five spring training games with the Yankees before being released.

But outside of maybe Holliday, Bautista hit the highest highs and experienced the most success of any member of that list; even including Holliday, Bautista supplied the most memorable season and single moment of a surprising, impressive, and impactful career. Now, he’s an unfortunate victim of a new market trend, but he was previously the forerunner of two more welcome developments in the sport. Every future Justin Turner or J.D. Martinez or other one-time fringe hitter who becomes an All-Star thanks to a swing change will owe a small debt to Bautista, and every emotive bat flip will recall his greatest moment in the bigs.