Welcome to The South Week at The Ringer. For the next several days, we’re celebrating — and reporting on — the richness of the region. You’ll find stories from all over the map, exploring topics such as the enduring legacy of Confederate monuments in Richmond and Montgomery, the evolution of Charleston barbecue, and the intersection of faith and football in Lubbock. We’re also ranking the best Southern rap albums, imagining the André 3000 mixtape we all deserve, and arguing about what even constitutes the South anymore. In the words of two great Southerners, nothin’ is for sure, nothin’ is for certain, nothin’ lasts forever.

Cesar Espinosa remembers the first time he received instructions for what to do if he ever came home to find that his parents had been deported. It was 1993, and his mother, Olivia, explained it all to him and his older sister, Aura, as they sat inside the house they’d just moved to in Columbus, Ohio. By that point, his parents had already long overstayed their visitor visas, which granted them legal access to the United States for six months; they’d been in the country for three years. But, having moved from Houston to Columbus, Cesar’s mother suddenly felt more aware of the threat of deportation. After they’d moved in and gotten settled, she realized an important fact: The Espinosas were the only Latino family in their new neighborhood.

The instructions were as clear as they were overwhelming. “She gave us some phone numbers to call,” says Cesar.

Cesar is not a physically intimidating guy. He’s 5-foot-6, maybe 170 pounds. His voice is polite and soft, which is surprising given that he’s one of the most influential immigrant-rights activists in the country. You expect it to boom, or to vibrate the walls, or to wobble you a bit. Most times — at least in conversation, anyway — his words seem to evaporate as soon as they leave his mouth. Not now, though. Right now they’re heavy. Right now they’re atlas stones. Right now they’re unavoidable.

“They were numbers to places in Mexico,” he says. “That’s how we were supposed to reach her. She told my sister and me to make sure that we stay together and to call those numbers.”

Cesar was in a new city, and he didn’t speak the language. He’d just found out there was a chance he could arrive home one afternoon and find that both of his parents had been sent back to Mexico. He’d also just learned that, were that to happen, he and his sister would be responsible for finding them and stitching the family back together. And he’d also just learned that, were they unsuccessful, they likely would be taken into custody by child protective services. Because Aura was just 11 years old. Cesar was 8.

“Ohio was very hard for us,” says Cesar. “We felt very out of place. My sister and I actually had to go to this special school that was 45 minutes from our house because we didn’t speak English yet and it was the only one that could accommodate us. I remember I was afraid to even bring my lunch to school because the other kids there would make fun of me because it was Mexican food and they weren’t used to seeing it. We only made it a year there before my mom and dad decided to move us back to Houston.”

Cesar and his family were five of the estimated 4.5 million people living in the United States illegally that year. As of the most recent count, that estimate stands closer to 11.3 million. Through 2014, 66 percent of adults in the United States illegally have been here for longer than a decade. But that anxiety, that apprehension, that constant fear, is nearly palpable today in this community, the result of a rigid shift in policy during the first seven months of the Trump administration.

As we speak in August, Cesar sits behind a large desk in a small office in a part of Houston known mostly for its stores offering knockoff versions of designer items. His desktop computer is opened to an active company Slack channel, which he peeks at periodically. Two cellphones take turns buzzing every few minutes. A landline rings every so often. “Can I tell you a quick story about this phone?” he asks, pointing at the receiver of the landline phone. His voice turns soft again. “When we first started FIEL, we had a fake phone.”

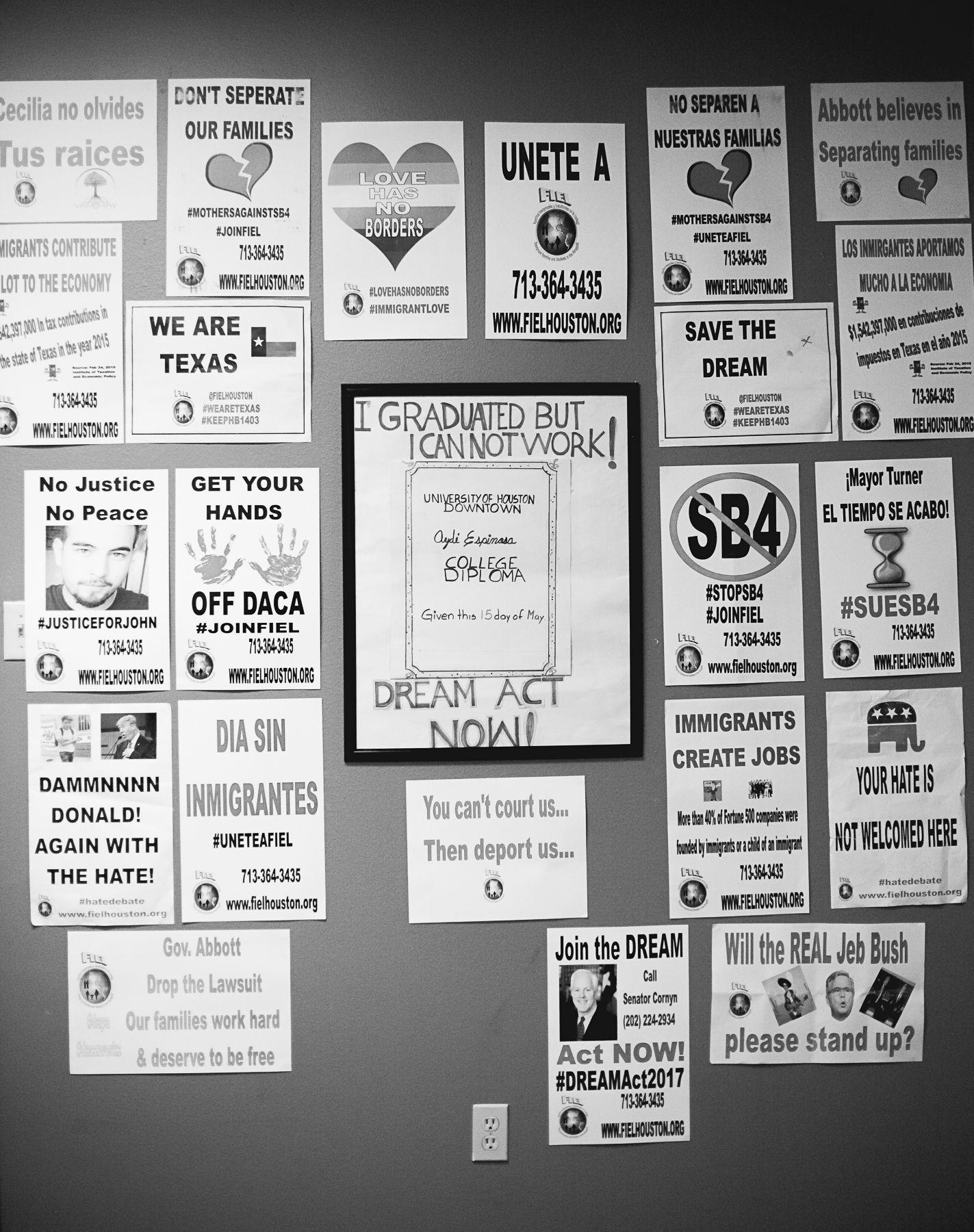

FIEL stands for Familias Immigrantes y Estudiantes en la Lucha, which is Spanish for Families of Immigrants and Students in the Struggle. It is a Houston-based nonprofit that advocates for immigrant rights.

FIEL serves as a voice and resource for young, undocumented members of the Latino community (though there’s been a push in recent months to reach other immigrant communities). Cesar, along with his mother, older sister, younger brother, and a group of about 15 students, started piecing it together in 2007. It started as an impromptu group, a tiny social activist club born of necessity, really, because there wasn’t one like it. It grew naturally, slowly at first, and then seemingly all at once. It became an official nonprofit in late 2011, and then a cornerstone for the Houston immigrant community after Barack Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy in June 2012.

The organization, which has more than 8,000 registered members, fields deportation calls and cases every day. It consists of three branches that oversee civic engagement, legal counseling, and helping undocumented high school students figure out how to get into and pay for college. Cesar says that it’s become the largest organization of its kind in Texas, and has cultivated national clout. At 32, Cesar is its executive director. They’ve progressed tremendously from the days of the fake phone.

“We had it on the desk just for appearance. There was a cord on it that plugged into the wall, but it wasn’t connected to anything because we couldn’t afford it. One time, this news station came by to do a story on us and they wanted some pictures so they asked me to pick it up and call someone so they could have some shots of us in action. I just pretended like it worked. I picked it up and dialed some number and acted like I was talking to someone,” he says, politely laughing at the thought.

“We’ve come a long way since then.”

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — more commonly referred to as DACA — was introduced by the Obama administration in 2012. It’s still in place. Its primary purpose is to protect the qualifying children of immigrants who’ve entered the United States illegally, because if you’re the child of an immigrant who’s entered the United States illegally it is nearly impossible to live a full, fulfilling life. The requirements to qualify for DACA are substantial: Applicants must have been younger than 31 as of June 15, 2012, and they need to have entered the U.S. before 16 and lived here for five or more years; and one is required to either be in school, a high school graduate, or the recipient of a GED. There are also stipulations regarding an applicant’s criminal record: A felony or significant misdemeanor conviction, three or more misdemeanors, or being deemed a “threat to national security” would disqualify someone from DACA. People who meet all these requirements can apply for a renewable two-year reprieve from fear of deportation.

Those who qualify under DACA can get a work visa and a driver’s license, and can apply for government benefits. Opponents of the order find it controversial because as opposed to the DREAM Act, which is legislation that has come up for periodic votes in Congress since 2001, Obama pushed through DACA by executive order. Nearly 800,000 immigrants have registered for DACA since it was implemented. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who is spearheading a campaign to get Donald Trump to repeal DACA, wrote in a letter to USA Today that DACA “represents an unconstitutional exercise of legislative power by the Executive Branch.”

The DREAM Act was something of a precursor to DACA. (The primary difference is that DACA allows for only a temporary reprieve from the threat of deportation, while the DREAM Act has proposed a path to full citizenship.) The act was first introduced in 2001 in an attempt to help protect the children of immigrants living in the United States illegally; these children became known as DREAMers. Various versions of the legislation have come up for a vote in Congress in the past 16 years, though all of them have had the same purpose: to allow DREAMers a chance at a traditional life in the United States. None of them, however, have passed. Generally, it’s Republicans who have blocked the DREAM Act’s passage, but senators Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) recently put forth a bipartisan effort to revive it. Many DREAMers have been raised almost entirely in the United States. And often, they will have nearly no connection to the country they left behind. But right now none of that matters. Because if you aren’t an American citizen, you aren’t an American citizen.

Cesar has lived in America for almost three decades, but he is still undocumented. Being undocumented in America presents an almost unfathomable number of challenges. There’s a stigma that comes with the label, and it’s as present within the Latino community as it is outside of it. (Cesar remembers the shock some of his friends expressed when he first told them that he was undocumented.) And so there’s always that part; the feeling illegitimate part, which is profoundly stressful. But there’s more to it, too. There are bureaucratically bigger things. Things that prevent you from living a proper life; things that prevent you from actually being legitimate. You can’t get a driver’s license in Texas, for example. Or a Social Security number anywhere. Or be legally employed. Or receive adequate health care. Or government benefits. You live in a gray fog.

The first time his undocumented status substantially affected Cesar’s upward mobility was his senior year in high school.

“It’s the DREAMer Moment,” he says. “It happens to us all.”

After Cesar’s family moved back to Houston in 1994, his mother enrolled them in a nearby elementary school. Back in Ohio, it had taken him only two months to become fluent in English. After that, school came easy. Cesar’s mother had graduated from high school early in Mexico and was two years into medical school before she quit so that she could bring her family to America. Cesar had academia in his blood. By the end of elementary school, he was, by all measures, in both English and Spanish, an exceptional student.

When Cesar registered for middle school, he was placed into the now-defunct Long Vanguard program, where students with high test scores were funneled. Despite a small setback during eighth grade (his parents were going through a divorce and he thought that torpedoing his education would bring them back together), he tested into several of the best high schools in Houston. One of them was DeBakey High School for Health Professions, one of the most rigorous and acclaimed schools in the country (earlier this year, DeBakey was ranked higher than 99.918 percent of 22,000-plus high schools assessed by U.S. News & World Report). He excelled there, and as he neared his graduation date he received acceptance letters from Yale, Cornell, and Brown, among many others. It was exactly the kind of thing his mother had hoped would happen for him when she decided to come to America. And then everything fell apart.

“I went into the counselor’s office. I’d watched friend after friend get these full scholarship offers but nothing was coming for me,” he says. “I’d done all the same work as them, and in many cases I’d done it better than them, and still: nothing. There were no envelopes. Nothing ever came.”

But Cesar knew why his offers never materialized: He didn’t have a Social Security number. Not having one precluded him from getting basically every scholarship he otherwise would’ve gotten. It didn’t matter that he was graduating near the top of his class at one of America’s premier high schools. It didn’t matter that he’d scored a 1598 out of 1600 on his SAT. It didn’t matter that he could speak two languages and play four different instruments and had completed hundreds of hours of community service. All that mattered was that he didn’t have anything to plug into those nine SSN boxes on the scholarship and financial aid applications.

“That’s the DREAMer Moment. When it happens — when that moment comes — you feel helpless,” he says. “You feel lost. You think, ‘Why me? Why do I have to go through this? I’ve done everything right.’ It’s hard. And you already have it in your head that you’re wrong. So who do you turn to? Where do you go? Who helps you?”

The only college that Cesar and his mother could afford was Houston Community College, so, starting in 2004, that’s where he went. He took one, sometimes two classes a semester if money allowed, working whatever jobs he could on the side. One day, his mother asked him to pick up some bird food from a PetSmart that was near campus on his way home. When he went in, he saw that the store was hiring. He knew that he couldn’t technically get gainful employment, but applied anyway. Similar to the forms he filled out for college, there’s a part on job applications where you have to fill in your Social Security number. When he got to it this time, he just scribbled in numbers until the boxes were full.

For Cesar, and for the masses of undocumented immigrants in a similar situation now, the risk was and is clear: You can pretend you have a Social Security number, and maybe you can get a job where someone doesn’t pay you under the table, an exceptionally fulfilling moment. Or you can pretend you have a Social Security number and potentially get caught and charged with a crime, which could, if things break against you, lead to your deportation. Cesar got lucky.

“I didn’t think too much about it,” he says. “I knew they wouldn’t hire me if I didn’t have that part filled in, so I just filled it in. I figured they would never bother to check it. And they didn’t.”

Once hired, he began grabbing any and every shift he could. Each time an opportunity came up, he reached for it. One year in — after the extra night shifts and weekend shifts and even obtaining a forklift driver’s certification because it came with a 25-cent hourly raise — management finally noticed him. They offered him an assistant manager position, which he gladly and proudly accepted. And then, just like before, everything fell apart.

“I guess they finally ran my Social Security number when they decided they were going to offer me that job,” he says. “They called me in and told me that the number I gave them didn’t match up. I quit right then. I was too ashamed. It was me being in that counselor’s office all over again. It was that same feeling. Everything I’d done to that point was just … erased.”

Cesar found himself forced back into the underground and unauthorized workforce, of which there were 8 million people by last count. He milled around a bit, working those odd jobs here and those pay-under-the-table jobs there, but was eventually able to wiggle his way into another ostensibly secure job, as a cashier at Fry’s Electronics.

“I applied on a Wednesday. By Thursday, I got a call back. They were really excited because I was bilingual and had experience working with computers. They said I got the job, to be there on Monday for some training. I was all dressed up when I showed up — black slacks, white shirt. I was very proud to have that job. I was there for half a day and then they called me into the office. I already knew what they wanted before I even walked in.”

It was his Social Security number again. It didn’t match. He tried to play it off, to pretend like it was just some sort of clerical mistake. He tried to talk them into holding the job for him while he sorted it out. They knew, though. Security escorted him out of the store.

“I was humiliated. It was really embarrassing. I sat in the car and cried in the parking lot for an hour. Everything was broken for me. I didn’t know what to do.”

As a student at DeBakey High School, Cesar had to complete 100 hours of community service to meet the school’s graduation requirements. His mother, who’d participated in political activism in Mexico, pointed him toward an immigrant nonprofit organization called the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN). It took all of one trip for him to fall in love. He started during his sophomore year, giving him three years to fulfill the 100-hour requirement. It took him less than a month.

“It was so exciting,” he says. “It felt important. I wanted to be a part of that. I went there every chance I could. They couldn’t get me to leave. It was one of the few places I could go where I felt like I belonged. It was very empowering.”

Cesar stayed active with CARECEN during his time at Houston Community College and PetSmart, and through luck or accident or destiny, they called him a week after the Fry’s incident to offer him a job. He threw himself into it.

But after a while, Cesar began to struggle with the organization’s central mission: “They were mostly concentrated on Central American adults, which I guess should’ve been obvious because of the name,” he says, laughing. “But I started to feel like, ‘What about the people like me or my sister or my brother or my friends? What about the [other] DREAMers? Where’s their support network?’ I’m not the only one out there. Who’s helping them?”

That realization fueled FIEL’s origin story.

From 2007 to 2010, Cesar worked with CARECEN, learning the business end of running a nonprofit, and also worked with his family and friends to establish FIEL. (He also transferred from Houston Community College to the University of Houston, where he graduated in 2010.) And during that period, his profile as an activist grew. He went from organizing smaller events and rallies to being named CARECEN’s community outreach specialist (he showed a knack for using social media to ensure that meetings and assemblies would be well attended). He started making appearances on local news stations and then on national ones. In 2008, he was named executive director of Houston’s America for All, an ancillary nonprofit started by CARECEN. That year, he was presented with an activism award by the city, and subsequently was honored with his own day by the mayor of Houston. He was 23 years old.

From 2008 to 2010, while Cesar was also handling a full workload at CARECEN, FIEL aggressively petitioned for the reintroduction of the DREAM Act. If it passed, the act would grant a pathway to citizenship to anyone who met the requirements (they were similar to DACA’s requirements). It was FIEL’s first big fight, and the thing that helped establish it as a genuine organization. They protested, worked the phones, staged sit-ins. They were a force. And the initial indications were that their work was going to pay off. Which is why when the Senate failed to vote to stop a filibuster in September 2010 — and then again that December — it was so devastating.

“We really thought it was going to get through. I remember we were all sitting in this conference room watching the vote and I figured out that the numbers weren’t in our favor a little before the others and I just sat there, totally silent, trying to figure out what I was going to say. People were crying. There were news cameras there because everyone was anticipating we were going to be celebrating. It was really bad. If it’d have passed, me, my sister, my brother, we’d have all been eligible. We’d have gotten our temporary citizenship. I was finally going to get in. I had real hope. So many of us did; hundreds of thousands of people. And it was taken. It was a tough day.”

Nevertheless, FIEL persisted. By 2011, it had become a certified nonprofit and Cesar was the face of the organization. In 2012, he received a request to come to Washington, D.C., from the office of Cecilia Muñoz, then the director of the White House Domestic Policy Council in the Obama administration. He’d been invited there along with about 30 other immigrant leaders from around the country. She spoke with them about how the White House had heard their concerns, and told the gathering that help was coming soon.

“We were all in there in this room together and we were like, ‘No. You all keep saying that. Why is this going to be different?’” says Cesar. “It was frustrating. I was thinking about the DREAM Act again. And that’s when she says she has someone who’d like to speak with us about it. The doors open. President Obama walks in. It was unbelievable. We were all in shock.”

Like Muñoz, Obama assured them that their voices had been heard, and that their lives and their rights in America were important. A few weeks later, on June 15, the 30th anniversary of a Supreme Court ruling against public schools charging illegal immigrants tuition, DACA was announced.

“That was a moment of ecstasy,” says Cesar, his smile stretching toward his ears. “It felt like … we finally got something. It felt like, ‘My life is about to change. So many people’s lives are about to change.’”

When the White House announced DACA, FIEL became the only place that mattered to undocumented immigrants in Houston and beyond. A line stretched through its building, down the stairs, across the parking lot, and down the block. People slept in it to make sure they’d be seen. Part of the requirements to qualify for DACA were that you had to prove residency in America for at least five years. Unsure of what would or wouldn’t count as proof, people showed up with suitcases of paperwork. They had certificates of achievement from kindergarten, old utility bills, handwritten letters, pictures, everything. It was mania those first few weeks; a constant stream of people and news crews and 100-hour work weeks for FIEL’s employees and volunteers. They’d never been more tired. They’d also never been happier.

Certainly not everyone who applied for DACA qualified, “but it didn’t even matter,” says Cesar. “All of the stuff that was happening around the decision. … It felt like that was the feeling I was chasing for so long.”

At the 46th minute of the June 16, 2015, speech announcing his intention to run for president, Trump made a bold proclamation: “I will immediately terminate President Obama’s illegal executive order on immigration.” He was talking about DACA.

At the time, the threat seemed silly — for one, because he was Donald Trump, and it seemed like there was no way he would ever be elected, and for two because he said it literally three seconds after he’d finished promising to the crowd that he would “never be in a bicycle race, that I can tell you,” which is an odd thing to say right before you let the country know you’re planning to upend millions of lives if you’re elected. Now, though — obviously, clearly, definitely — it seems less silly, and certainly more dangerous.

“Watching Trump get elected was very painful,” says Cesar. “We didn’t expect it. All the preliminary polls leading up to that night had Hillary ahead. Her husband did some things with immigration in 1996 that were very harmful to our community,” he says, referring to the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which as Vox’s Dara Lind put it, “invented immigration enforcement as we know it today.”

“But we [FIEL] still felt like we were going to be better off if she’d been elected because of the things Trump was saying during the campaigning.”

President Obama pushing DACA through as an executive order made it what the DREAM Act was never able to become, which is to say it made it official and real. But his action also made the policy vulnerable. Trump can, almost unilaterally, end DACA at his discretion. There’s been a push from the community at large to keep it in place (a 2016 polling showed that 60 percent of Trump supporters are in favor of letting undocumented immigrants currently in the country stay legally, if certain requirements are met, and that number goes up to nearly 80 percent among all voters). But there’s been a substantial push to remove it, most powerfully the aforementioned campaign by Ken Paxton, who has formed a 10-state alliance that has threatened to sue the federal government if Trump doesn’t rescind DACA by September 5.

The rescinding of DACA is what FIEL and the undocumented immigrants it serves fears more than anything in a long-term sense. It would instantly upend the lives of the 800,000 people currently registered for its protections, and that’s to say nothing of the ramifications it would have in the immigrant population as it rattled outward.

More immediately, what most scares the masses of people who would be vulnerable under a rollback of DACA is ICE, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. This is the part of the federal government that deports people. Trump’s hardline stance on immigration has led to what appears to be an escalation in unnecessary detentions (and, potentially, deportations). Per The Washington Post, 4,100 immigrants who had not committed a crime were arrested in June, “more than double the number in January.”

Under President Obama, ICE prioritized deporting convicted criminals. Under Trump, however, ICE has seemingly prioritized grabbing any undocumented immigrant it can.

An example: In March, the Houston Chronicle ran a story about Jose Escobar, a 31-year-old man who’d lived in Houston since he was 15. He had no criminal background. Escobar was also married to an American citizen, and he was the father to two American citizen children. But he lost his temporary deportation protections when his mother accidentally didn’t include his paperwork when she filed for a renewal. (Since he was a minor at the time, she assumed that his renewal would be attached to hers.) When he went to his annual check-in at the immigration office, he was arrested and deported back to El Salvador, a country he’d not been to or even seen in 16 years.

The fear of being insta-deported is such a staggering concern that it’s caused a decrease in the reporting of crimes in immigrant populations. In Houston, for example, reports of rape in the Latino community have dropped by nearly 43 percent.

“It used to be that we’d get one or two deportation cases or calls about every six months,” says Cesar. “Since Trump has started, we’re getting three or four calls a day. There’s real fear in these families. People are terrified. Before, if you did everything right then you felt like you’d be fine. Now, everyone feels like they’re in limbo, like they can be deported at any time, because that’s what we’re seeing.”

FIEL’s current fight exists on multiple fronts.

First, the organization is attempting to pressure Paxton into ending his crusade against DACA. (FIEL can have no direct impact here, but it can show up wherever he is and protest him, which is what they did earlier this month when he appeared in Houston for a scheduled appearance.)

Second, FIEL is working against the enforcement of a recently passed immigration-enforcement law that will, in effect, remove Houston’s sanctuary city status. A sanctuary city is one where local officials do not fully comply with federal immigration authorities. FIEL’s fight against the bill, which goes into effect on September 1, will be a long legal battle. Its goal is to file a lawsuit that would eventually be heard before the Supreme Court; it’s a plan that could take upward of a decade.

But perhaps most urgent is the organization’s handling of the sudden overload of ICE seizures and deportations, which is tied in so tightly with the crusade against DACA and the pending Texas law that there’s no real way to prevent them from happening, only ways to respond quicker to them when they do.

Cesar’s mother eventually remarried to an American citizen, so she gained her citizenship that way. And his younger brother was just young enough at the time of DACA’s implementation that he qualified for it, too. For Cesar, though (and for his older sister), short of marriage there is no way to gain permanent citizenship in the United States. As the law exists today, the soonest Cesar believes he could be granted citizenship would be about 18 years from now, and that would include having to live in Mexico for anywhere from three to 10 years as a penalty for how long he’s been in America undocumented. That would put him at 50 years old. That’s the best-case scenario.

“It could take up until I’m 60,” says Cesar, “or I could even wait all that time and still not get in. But it’s not about me. It’s about the others.”

I remind him of the conversation he had in that house in Ohio, and I ask him if he thinks that somewhere, right now, in some house or apartment in Houston there’s a mom talking to her kids about what to do if they come home one day to find that she’s been deported.

“Yes. Absolutely.”

When I ask if he thinks FIEL’s is one of the numbers those parents are writing down, he goes silent for a moment. When he speaks, his words are heavy.

“I hope so. I think so.”