Welcome to Inefficiency Week. Over the next five days, we’re going to take a look at what we lose when we get lost in the chase for efficiency. We’ll explore the ways it’s changing the games we love to watch. We’ll remember its failures across the pop culture spectrum. And we’ll report on what it’s doing to our lives — romantic, physical, and otherwise.

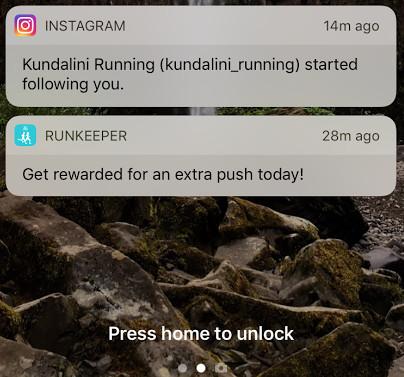

"Let’s work out! You thought this was the perfect time a while back … remember?"

"It’s been a week since your last workout!"

"It’s Sunday Runday! Start the week strong!"

Old me — which is just me, three months ago — would’ve thrown my phone, with this glut of notifications, across the room. New me feels every pixel of their intended guilt. I pull out my shoes, I head to my car, and I drive to Portland’s Forest Park to run at least 10 miles. Somewhere around mile 6 is usually when I start to wonder how exactly I got here — and also when it starts to feel good.

Once upon a time, I was the poster child for not running. A birth defect meant I had procedures, surgery, casts, corrective shoes, and leg braces from birth through the early years of high school. One of my legs is longer than the other. One foot is bigger than the other. One calf is stronger. One foot has a normal number of tendons, so it can flex normally; the other doesn’t. I have always felt that my body is a study in asymmetry. These unlike halves meant I was not made for running — hell, without correction, I was barely made for walking.

So I mostly didn’t, with the exception of the occasional short run — until April, when I decided to go on a hungover 8-mile run with a runner friend. The monotony of the gym had begun to seem overwhelming, and my ragged body needed to do something to power through self-poisoning. I expected to be left far behind by my friend or maybe even to throw up; neither happened. After that, feeling ultracapable, I decided to run 10 miles. I timed the run and shared the result with the aforementioned friend, who told me it was, and I quote, "fast." I was fast?! I have never been fast; strong, sometimes; determined, very; strategic, sure. But fast? Not remotely.

So I kept running, because, like many people, I am pleased when I find out I’m good at something. Eventually I got used to the novelty of plain running, so I decided to set some goals; I signed myself up to run two half marathons and a 15-mile leg of a relay marathon, all in the course of two months.

This is about the time when the apps took over. I’ve never calculated my workouts in any way — no calories burned, no heart rate tracking, and never my speed. But I still didn’t really think of myself as a runner, and using various running technologies helped assuage my amateur anxieties; my phone and apps became a database for my progress, and my progress became a fixation. Now I think in 5K-, 10K-, and 13.1-mile increments; in mile-time splits; in average pace; in distance divided by time. I have my finishing places (26 out of 225 overall in one half marathon, and 111 out of 906 in the other) memorized. I’d love to tell you about my best half time so far (one hour and 58 minutes) and my new goal for that distance (one hour and 50 minutes).

Running is simple. But I, with the help of some demanding technology, have managed to complicate it. The last three months have been fueled by a small arsenal of apps, equipment, and playlists that have turned me into a pavement beater with a desperate compulsion to best myself. Their promise was that I would become a better, more efficient runner; I would have hard data that went far beyond the capabilities of a lowly stopwatch and a gut feeling of improvement. But somewhere along the line, technology went from complementary to supplementary in my training. The apps turned a solo leisure activity into an obsessive, not-always-healthy pursuit. Throughout my training, I couldn’t tell if I enjoyed the intensity or whether I’d allowed another set of technology tools to take over my life. But I do know it worked.

Like any worthwhile hobby in 2017, running is the focus of a variety of apps that can help you refine the experience. By "refine," I mean "become completely possessed by." There are apps like 5K Runner, which focuses on getting you from the couch to a 5K, and Runtopia, which is focused on coaching you. Early in my training, I perused a handful of these options but had trouble finding a good fit: Lumo required a wearable, which costs at least $100; the competitiveness of Strava honestly scared me; Nike+ Run Club seemed too professional for my extremely amateur state. I finally settled on Runkeeper, which felt friendlier and featured no photographs of beautiful, cut people running. The app can be used to race other users or virtually "run" with them, which just means running the same distance and comparing stats. There are challenges where you can race people around the world, and a feature where you can set goals for yourself. And then there is the "Me" tab, where all of my Runkeeper activity lives.

I use only two buttons in Runkeeper: "Start" and "Me." I love to mindlessly flip through my stats. I can see how long I’ve run month to month (8 hours and 46 minutes in May; 11 hours and 55 minutes in June) and how many calories I’ve burned during those runs each month (7,112 in May; 9,682 in June). And of course, I can see how many miles I’ve covered in each, the most important stat (63.2 in May, 85.3 in June, and 76.2 so far in July). Each log includes a map, my mile splits, my elevation gain, and sometimes a photo if I added it.

Each month, these numbers — and my time spent in the app — climb. I can feel myself coming closer and closer to ponying up the $9.99 a month to buy Runkeeper Go, which will give me deeper insights into my running and compare my workouts. (This is huge: I have a hard policy of not paying for apps.) I have come to know the voice that tells me "Activity started" when I begin a run, and I noticed immediately when it was changed in an update. (She speaks with a different, faster cadence now; the Runkeeper team tells me they recently sped it up, but the voice is the same, provided by a cofounder’s wife. She feels like a friend.) Runkeeper has made me accountable more than anything else. The badges, the maps, and best yet — the occasional bragging.

I have never been one to post a before-and-after fitness pic or a sneaky gym photo, but a saved screenshot of my 10-plus-mile runs, complete with elevation climb and map info, accomplishes the same thing for me. Sometimes, when I am bored, I will thumb through my Runkeeper-tracked runs, scrutinizing the maps I’ve accumulated. My compulsion to track my runs is the same as someone else’s to Instagram their OOTD or their acai bowls. The difference is that I never use Runkeeper’s social features; instead, I hoard them for myself, scrolling through them obsessively, reliving them like I might during a nostalgic trip through Instagram or Facebook photos.

I have always preferred working out alone. Now I can work out alone and intensely analyze myself and this sport, all on my own, inside my phone. Runkeeper gives me a sense of self-satisfaction while also motivating me to push harder; it makes me want — not need — to run, which is something I have never felt.

According to the designers at Runkeeper, my obsession with their app and using it to compete with myself sounds normal. One major takeaway from their user interviews is that "most people hate running." "They don’t like it, they don’t look forward to it, but they love the feeling when they’re done," Chase Clark, who works on Runkeeper’s UX team, tells me. The other major user trend also feels uncomfortably familiar: "Everyone talks badly about themselves as a runner; they always knock themselves down a couple pegs. They’re always like ‘Oh, I’m not a serious runner,’ and then you go look at their history and they run 20 miles a week," Clark says. "People doubt themselves is what we’ve heard from these interviews."

Runkeeper remains my app of choice for various reasons, but it has the same objective as Nike+ Run Club and Strava and all the rest: gamifying something that is otherwise done alone. Race yourself, track your stats, virtually run with other users — these features manufacture a sense of motivation and even companionship (be it with the other users or just the voice inside the app coaching you) that otherwise doesn’t exist. They help reassure, yes, but they also incentivize. There is very much a proverbial, digital carrot being dangled in front of the user, and naturally (literally), we run after it.

The pain started during one of my first long runs, around mile 8. My knee hurt. For the rest of the run, I just thought of ways to describe the pain: It felt like my knee had been hollowed out, and that at any second the bones surrounded by what used to be tissue and muscle would shatter into pieces. Or it felt like some sort of rubber band that was once tight and flexible had suddenly lost its elasticity and was just dangling around in there, the bones no longer held together correctly. I kept running, though, because — as I often think to myself toward the end of distance runs — the faster I run the sooner I can stop running. I hit mile 11 and kept going, even though all the warning systems in my body were telling me to stop.

All these physical signals — the knee pain, the weird, ragged breaths and sounds I was making because of it — were not enough to make me quit, but an app I’m obsessed with finally did. Shortly after mile 11, my phone died. The carefully selected music, gone. The Runkeeper tracking, turned off.

It is not fair to blame Runkeeper for this questionable decision-making, both because it is just an app, and also because it is not the only app I use. At some point I signed up for Achievemint, an app that pays you for working out. It’s largely meant as a motivational tool; you don’t want to get off the couch, but you could earn points toward a PayPal deposit, so you do. For me, it’s more like "I’m about to go run 10 miles anyway, why don’t I let someone pay me for it." There are no bounds to my frugality.

Achievemint was launched in 2013 to, as I’m told by a company spokesperson, "empower people to control their own health journey." The platform allows you to connect any number of fitness apps and then pulls in the activity that’s being logged there. I, obviously, connected Runkeeper. The exchange rate is 10,000 points for $10, and I can tell you, earning those 10,000 points is not easy. My 10-mile run netted only 70 points; currently, I’m sitting at 1,514 points total. Still, the idea that eventually the thing I am doing anyway will earn me a couple of bucks is as close to being a sponsored athlete as I’ll ever get. I love it.

From there, I found my way to Running Instagram. A certain subset of us are particularly susceptible to Instagram porn — for you, it might be decadent food photos or images of succulents. For me, it’s always been wilderness porn, which extends to #vanlife and #tentlife, and eventually grew to include the trail-running community. Then I found myself firmly entrenched in Running Instagram. (Runstagram? Sure.) Whatever frighteningly accurate algorithm is employed to create the Explore tab started including popular running accounts around the time I began logging some serious Runkeeper hours. (No, I don’t think these two things are related; my increase of run-related Google searches and Facebook RSVPs to half marathons likely triggered this.) At first, I just followed a good meme account, but it was enough to recommend me to other runners. Regularly I get a follow from what appears to be A Very Serious Runner and I feel slightly embarrassed knowing they will be disappointed in my lack of running content.

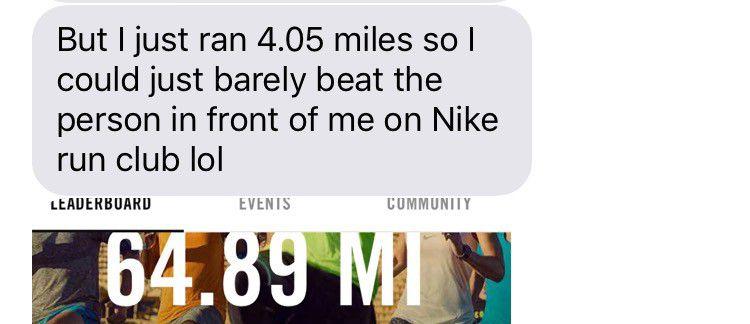

But as with any other effective Instagram channel, skimming through #running or #runlife is a double-edged motivational tool. The same impulses that prodded me to impress my Runstagram friends are the impulses that led me to keep pushing toward those half marathons, even through physical pain. And eventually I found myself so reliant on Runkeeper that I refused to use the auto-pause feature (which pauses your run if you need to stop) because it wasn’t pausing quickly enough. I held my phone tightly, manually pausing and restarting it every time I came to a stop light or took a drink of water. I’d run like this for 10 miles, sacrificing comfort — and likely, speed! — so I would have better stats on my phone. I am not alone; my runner friends have similar impulses:

Efficient? Maybe on the app’s terms, but certainly not otherwise. I have lost count of the number of times I have skipped a strength-training workout because the pull of my pitiful miles logged or my sad Achievemint score have called me to the trail. Inside the platforms, I am efficient as hell; in the real world, not so much. Runkeeper and Achievemint made me want to earn points and defeat a game; and initially, they fed my ego, not my health or happiness. None of the apps or running Instagram accounts were able to tell me my knee pain was probably being caused by an overly strained IT band. To find out how to fix that, I would have to look outside my phone and talk to people.

I have always had a complicated relationship with shoes. I was born with the aforementioned defect, talipes equinovarus — a fancy word for clubfoot. My right leg was curled back, and my foot smashed into a tiny "C." I had an Achilles tenotomy as an infant, a ton of casts and braces throughout childhood and later, and I also went through a strange period of time where I shopped for one foot in the children’s shoe department and the other in the women’s.

Three years ago, I bought my first real running shoes from a company called On, headquartered in Switzerland but with an office and storefront in Portland, Oregon. (To be clear, this only eased me into the occasional short-distance run; I’m talking about 3-ish miles every few months.) They have a unique design that locks and pushes, seemingly helping lift you off the ground. (At least that’s the idea.) Cofounder Olivier Bernhard created the shoes with the help of a Swiss engineer; their goal was to re-create the feeling of running on clay tennis courts — a certain bounce to your step and cushion to your fall. "I put on a pair and went from hating to run and immediately feeling like ‘Wow, this is different,’" says cofounder Caspar Coppetti. "It took away the pain, but it also made running more interesting."

The shoes helped support my ankles, and my knee pain eased. Immediately, things stopped hurting. But as all running shoes do, they eventually wore down. For my next pair, I decided I was going to go into Foot Traffic, a local running shop that has long intimidated me. Years ago, when I first lived in Portland, I used to go to a gym next door to Foot Traffic. I’d pass shoppers getting their gait examined or runners meeting for a club and stare at them like they were another species. I was confused by them, but also a little jealous: They had an excitement and an adrenaline for their workout I didn’t as I sullenly headed to my elliptical, where I would stream Netflix and essentially move a machine that moved my body.

I was also intimidated by these people, who very much looked like runners — real runners. I still felt like this when I went into their shop two weeks ago to get my own gait analyzed, but a kind Foot Traffic expert named Aly Pavela assured me that I count as a runner. She also nicely explained to me all the many things I’d been doing wrong. What size were my shoes? Seven and a half, just like all my shoes, I said. That was wrong, apparently: You’re supposed to size up one to two sizes to avoid the risk of plantar fasciitis or black toes. I told Pavela about my knee and ankle pain, and we talked about foam rolling; she explained how you could hack together your own foam roller with some tennis balls. And then we analyzed my gait, which involves stepping onto a treadmill and walking while video records from the knee down. She showed me the video using a software called Dartfish, which can help analyze the angle of the knee to ankle as the leg moves. It showed how much or how little I was pronating, which happily wasn’t too much (though it was clear how differently my left and right legs were working). Only then did we try on shoes (which is how I came to buy my third pair — running is expensive).

As I was leaving, Pavela told me how cool it was that I was running despite my early issues with my foot. "I just think it’s so cool when people run when they were told they shouldn’t or weren’t supposed to. That’s awesome!" The boost felt almost as good — maybe better? — than lying in bed and scrolling through my Runkeeper miles before falling asleep.

Inspired by my Foot Traffic experience, I decided to seek out feedback and advice from other runners and experts. My friend Alyssa, the runner who originally got me into all this, turned me onto Epsom salt baths and (again) foam rolling, two things that hugely eased my aching IT band and swollen ankles after races. (She also advised me not to run the day before a race, which I hastily ignored after a Runkeeper prompt popped up on my phone. Technology wins again.) Alyssa is the person I sent screenshots of my times to; her positive feedback was easily more reassuring than any faves I got from posting screenshots of my runs to Twitter. My friend Rachel told me that if I ever choose to run a marathon, I should expect to cry and break down at some point; this is definitely advice I need to know, and something that even $10 on Achievemint wouldn’t get me through. Jen Davis, a physical therapist and coach I emailed about running with a club foot, told me that while she couldn’t make a diagnosis over email, she thought it’d be useful to know that I’m likely more prone to shin splints. (She’s right; when my shin splints were at their worst, even touching my right shin with a fingertip felt like bone might rip through my skin. I once mocked an ex for complaining about his shin splints and for this I am truly, deeply sorry.)

Now I realize the best help I got during any of this didn’t come from an app or gait analysis or even my very important shoes. When nerves were setting in the night before my first race and I was sure I would somehow fail at this thing I was suddenly so devoted to, my boyfriend (who has run a marathon) reminded me that what I had to do was simple: I just had to run and not stop until I reached the finish line. There was nothing else to think about or make sure I was doing. I could slow down, I could even walk, but I wouldn’t fail; all I had to do was just run until I was done.

Last weekend, I finished my last race for the summer, 15 miles on a relay team at the base of Mt. Adams in Trout Lake, Washington. It was the most I’d ever run, and it hurt. But now that it’s over, I keep thinking about what’s next. I know that I need to be more responsible about it, but I still want to use Runkeeper to collect more miles, to keep whittling my time down. I want to continue in my pursuit of shoes that correct my mangled foot as much as possible.

A significant part of what originally attracted me to running is that I can do it on my own. But I am a big proponent of being alone together, and thanks to technological improvements, this is what running feels like. Flying down my trail of choice in Forest Park, I exchange nods with other runners; at races we all line up together, splintering off on our own, lost in our own heads and playlists but sharing the same route. Apps and a phone and new shoes got me to run and taught me I was good at it. These things absolutely made me better in the technical sense of the word. (Here, look at my improving times, saved to Runkeeper, for proof!) The apps managed to tick into that part of my brain that wants to create a quantified database out of my body, and for this, I’m thankful. But the technology isn’t what made me love the sport, or even what made me better at it. The actual, physical running did — and that’s why I’ll keep doing it.