"What’s in a name?"

The late William Shakespeare once dared to ask that question through the lips of Juliet in his famous play, Romeo and Juliet. And here I am, over 400 years after he finished his masterpiece, giving it a different twist, repurposing it, and asking that question again for perhaps a slightly different, if irreverent, purpose.

What’s with the name "Frank"?

There are a couple of reasons for this exploration. First, it’s the Fourth of July, an extravagant day when America celebrates itself and consumes about 150 million "franks." The name for what we now typically call a hot dog, "frank," was given to the beef and pork sausage sandwiched (not to say that a hot dog is a sandwich) in between a long bun because the concept was born in Frankfurt, Germany. According to the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council, God bless them for their service, the period from Memorial Day to Labor Day is called the "Season of Seven Billion Hot Dogs." That’s a lot of franks. Which brings me to my second reason.

Right now, there’s a sudden influx of Franks in the NBA. Of this year’s 60-player crop of NBA draftees, three were named Frank: Frank Ntilikina, Frank Jackson, and Frank Mason III. In 2015, Frank Kaminsky was picked ninth by the Charlotte Hornets, making him the first Frank in the league in over a decade. That’s four Franks in three years after 11 years without one. We are in the middle of a Frankeissance.

The name "Frank" may have its roots in a combat weapon. A frankon, or a Frankish spear, was a weapon used by the Franks, a Germanic tribe from the medieval times — though it is unclear whether the name or the weapon came first. Between the third and fourth centuries, the Franks settled into the area which, in the modern day, is occupied by France and the Netherlands. From there on, Frank surged as a first name, and was taken to England, where it was popularized, and then to the United States.

Over time, Frank has become synonymous with the name Francis, and though many are born as the latter, they grow up to take on the former, more casual iteration of the name. For the purposes of this exploration, however, we are sticking to the original form only, and thus are not including other iterations such as Fran, Franklin as a last name, or Frankie, unless it’s used as a nickname for Frank. I’m sorry. Those are the very serious rules I’ve made up.

The number of Franks in the United States is dwindling. Despite adorning the identification cards of famous people like actor and singer Frank Sinatra, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, director Frank Capra, comedian Frank Caliendo, and most recently, singer Frank Ocean, numbers say it’s never been less popular than it is right now in 2017, and that the name has seemingly run its course.

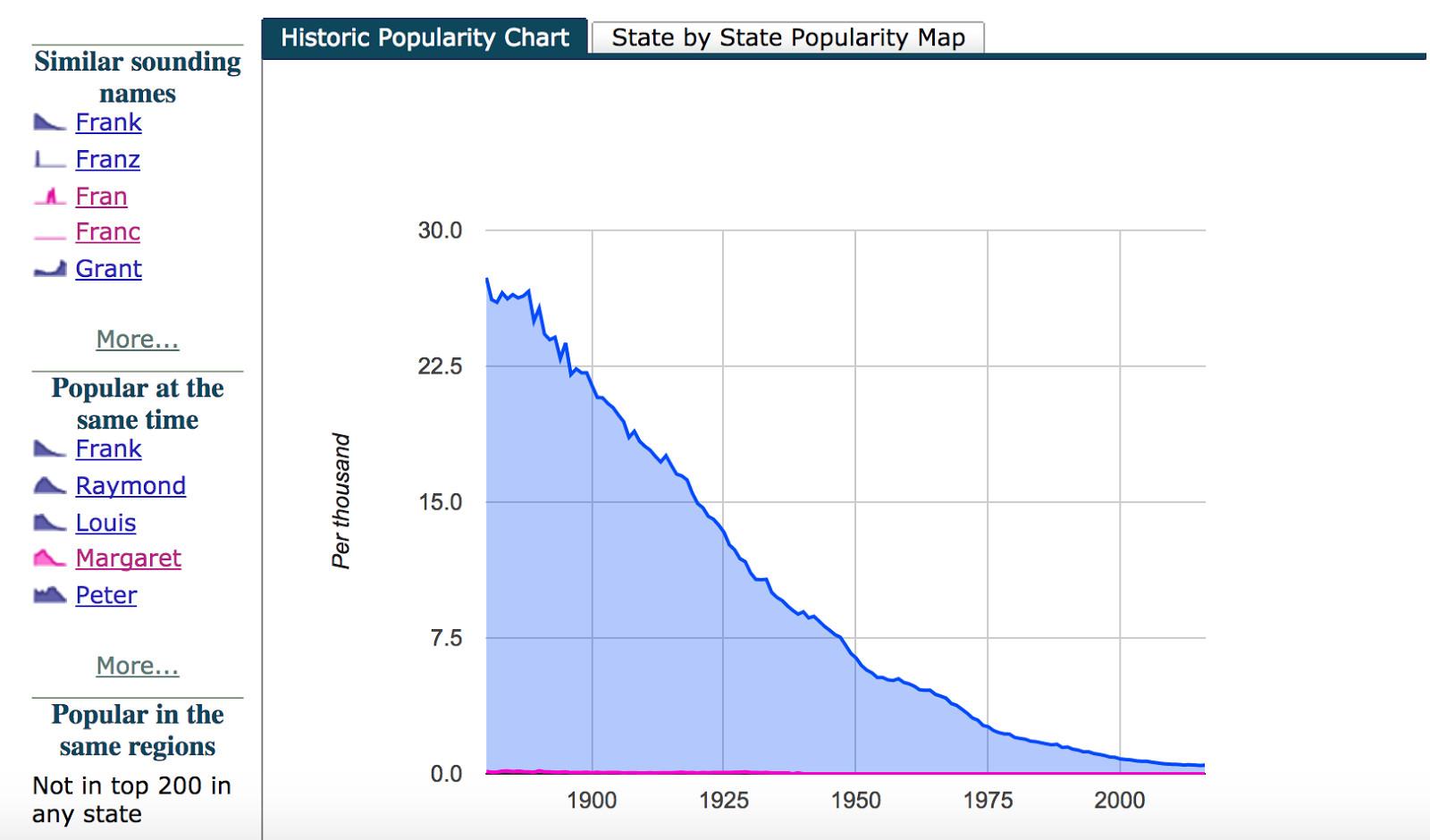

The Social Security Administration has baby name data that goes back more than 130 years. Since then, the use of the name Frank has been in decline. This drop has steepened over the past 30 years. The peak of Frank popularity was the 1880s, when it was the sixth-most popular baby boy name. In 1880, neither pro American football nor basketball had begun, Rutherford B. Hayes was president, and you couldn’t drink a Coke because neither Coca-Cola nor drinking straws had been invented yet. The name Frank ruled in a much simpler world.

Frank stayed in the top 10 until 1921, and in 2016, it reached rock bottom, falling to no. 355, the lowest ranking of baby boy names it has ever held. In 2016, only 0.047 percent of all boys born in the United States were given the name Frank. That’s down from almost 3 percent in 1880.

Frank is a dying name, just don’t tell that to the NBA.

Before 2015, the last Frank in the NBA was Frank Williams, who played a total of 86 career games for the Knicks and the Bulls from 2002 to 2005. No Frank played a single game in the league, or even got drafted, until 2015.

"[2017’s] drafted Franks were born around 1998, when 0.093 percent of boys received the name. It is surprising to have so many of them," Mike Campbell, the man behind the website Behindthename.com, which keeps track of name trends and origins, told me via email. Jackson and Ntilikina were in fact born in 1998; the former was actually born "Franklin," which Campbell says is even less common, while the latter was born in Belgium, a country in which the name Frank is just as uncommon. "If you look at Belgium’s neighbors France and the Netherlands, you can see it’s even less popular of a name there than in the States."

Now, Kaminsky is going into his third season in Charlotte after two subpar years, while the trio of Ntilikina, Jackson, and Mason all have their work cut out for them. Ntilikina, a promising foreign prospect, was drafted by the Knicks in the top 10 and projects as defense-first guard with, not surprisingly, a lot of "raw potential." Jackson was once a five-star recruit; he was overshadowed by Duke’s other top players this past college season, but still decided to declare for the draft, landing in New Orleans after being taken with the 31st pick. Mason, meanwhile, enters the league as a Sacramento King after four legendary years at Kansas, but with a limited physical frame that will need to be eclipsed by his toughness and his skill.

To properly chronicle the development of the name Frank in basketball lore, we must first go back to the very beginning. On November 1, 1946, the New York Knickerbockers and the Toronto Huskies played each other in the Maple Leaf Gardens of Toronto. It was the first game in what would become the NBA, and there, buried deep in the depth chart of the Huskies squad, was a Frank.

Frank Fucarino. Or as I will refer to him here, "The First Frank."

The First Frank barely played in that now historic game, in which his team took a close loss, 68–66. But Fucarino did not go scoreless. The First Frank stepped up to the line during the game, and sank a single free throw.

The First Frank aside, the late ’40s and early ’50s was the golden age for Franks in the NBA. Not only did we have the largest number of Franks suiting up, we also had the best and most interesting.

Aside from Fucarino, whose only claim to fame is his appearance in that first game, there was Frank Brian, who also played in the NBA’s first seven seasons after winning a title with the Anderson Duffey Packers (a real team) in the National Basketball League. There was Frank Kudelka, nicknamed "Apples," who played for five different teams in his four seasons in the league from 1949 to 1953. Frank Selvy, the no. 1 overall pick in the 1954 draft and a two-time All-Star who played 10 seasons, but sat one out to serve in the military. And then there’s Frank Baumholtz, nicknamed "Frankie," who is basically the reverse Michael Jordan.

Baumholtz was an All-American basketball player at Ohio University. After leaving college, he played minor league baseball for two seasons, followed by 10 years of major league baseball on the Cubs, Phillies, and Cincinnati Reds from 1947 to 1957. In Baumholtz’s first year in the majors he also decided to play basketball for the Cleveland Rebels, part of the Basketball Association of America. During his lone season there, he played 45 games and averaged 14 points on 19 shots a game! For context, that’s more than three times as many shots as Kobe Bryant averaged during his own rookie season, and more than he averaged in all but three of his 20 seasons. Baumholtz never returned to basketball, but what a legendary season of chucking he had.

Yet the godfather of the NBA Franks, and the most famous Frank of that era, is Frank Ramsey. Ramsey won an NCAA championship with Kentucky before playing for the Celtics and pioneering the role of the sixth man on his way to seven NBA titles with Bill Russell’s Celtics. Ramsey was an unsung hero of those legendary Celtics, even though he had to take a year off to serve in the military. By the time he capped off his career in 1964 with his final championship, Ramsey was a surefire Hall of Famer — the only Frank in the hall to this day.

By comparison, the late ’60s and the ’70s were a dark time for the Franks in the league. Of the six NBA Franks who started their careers after 1960 and before 1980, four of them played only one season, and one of them (Frank Oleynick) played only two. Once Frank Johnson arrived in 1981, he gave the name a new look by averaging nearly 10 points and five assists a game — the best numbers put up by a Frank since Ramsey — before going overseas in 1989 to play three years in Italy and France. Call it going back to his roots.

Frank Brickowski followed Johnson, and played the longest career enjoyed by a Frank so far — 13 seasons from 1984 to 1997 — after which we awaited the century’s first Frank. That would be Williams, the two-year disappointment from 2002–03 to 2004–05 drafted 25th overall, whose early exit from the league left us with a Frank-less NBA.

But now, the next wave is here.

The sports world outside of basketball has also familiarized itself with the name Frank through some its biggest stars. In baseball, there was Frank Robinson and Frank Thomas, both of whom smashed over 500 home runs in different eras, won two MVPs, and find themselves in the Hall of Fame. In the NFL, there’s Hall of Famer Frank Gifford and the active Frank Gore, a five-time Pro Bowl running back who is set to begin his 13th season in the fall.

In football, there are only three active Franks, including Gore, and only one has entered the league within the past seven years: Seattle’s Frank Clark. In baseball, there is not a single active player with the name Frank, only two with the name Franklin, and one with the name Frankie.

The numbers, in sports or otherwise, don’t have to convince you that the name has aged poorly. According to the name website Nameberry, Frank "still has a certain warm, friendly real-guy grandpa flavor that could come back into style." "Real-guy grandpa flavor" are words that should never be used together.

This makes the sudden entrance of four NBA Franks in three years that much more bizarre and uncanny. Sure, it’s random, and likely has no explanation. But Frank Sinatra passed away in 1998, so who is to say that many mothers around that time weren’t inspired to name their kids after Ol’ Blue Eyes?

Regardless, the numbers don’t lie about Frank, and neither do the projections about the name’s demise — in basketball or otherwise. Most 2018 and 2019 NBA mock drafts don’t project another Frank to be drafted within the next few years, and ESPN’s recruiting rankings don’t have a single Frank included all the way through 2020.

We may have just received the last influx of Franks ever. So, grab a frank today, take a bite and sit back. Turn on your TV, and while you relish the hot dog eating contest, think of the Franks — of those being inhaled and of those suddenly trying to make a career in the NBA. Root for Jackson, Mason, Ntilikina, and even Kaminsky. They may be the last wave of the name, but for now and the foreseeable future, these four players have ensured that we are in an NBA Frankeissance, which, to be frank, is a term I have made up.