Just four days after his on-deck circle sit-in and ensuing ejection produced the latest in his line of viral videos, Adrián Beltré is back in our highlights and our hearts. On Sunday, Beltré became the 31st major league player to record his 3,000th career hit, doubling off of Baltimore’s Wade Miley.

Unlike some hitters who’ve had to hang on well past their primes to reach 3,000, Beltré didn’t limp across the line. At 38, the defending Gold Glover — who ranks fourth in the majors in WAR since 2010, behind Mike Trout, Clayton Kershaw, and Robinson Canó — is having an injury-shortened but still-excellent season, hitting .312/.388/.543 in addition to his customary above-average defense. That historic double didn’t push Beltré into Hall of Fame territory, though; the milestone merely burnished a Cooperstown case that was already sealed. The only non–Hall of Famers with higher career WAR totals than Beltré’s 92.4 are the still-active Albert Pujols and three PED poster boys: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and the not-yet-eligible-anyway Alex Rodriguez (the only position player other than Beltré ever to amass at least 20 WAR with three different franchises). Beltré’s JAWS score — a statistical method of measuring Cooperstown credentials developed by Sports Illustrated’s Jay Jaffe — places him fourth among third basemen, behind only Mike Schmidt, Eddie Mathews, and Wade Boggs. And with a year remaining on his contract and no great decline to date, Beltré could climb that list.

Despite his unbesmirchable stats — both traditional and sabermetric and both peak and career — Beltré’s "complete lock" status has come late in his career compared with the fast-rising reputations of many equivalently accomplished players who were perceived as future Hall of Famers throughout their time in the majors. For years, Beltré was widely seen as inconsistent and an overpaid disappointment, and when his five-year stay in Seattle ended in 2009, the best contract he could command was a one-year, $9 million deal with Boston. Beltré didn’t even make his first All-Star team until his lone season with the Red Sox in 2010 when he was 31, which means he will be the only Hall of Famer who debuted in the All-Star era (1933–present) to not make an All-Star team through his age-30 season (aside from Satchel Paige and Monte Irvin, who made the majors late after spending years in the Negro Leagues).

Beltré’s late-developing reputation as an all-timer is partly a product of his atypical career trajectory: Not only has the third baseman remained an elite defender at an age when many formerly skilled fielders are relegated to part-time or DH duty, but he’s also been a far better hitter after age 30 than he was before, posting seven of his eight best seasons (by offensive WAR) at 31 or older. Only eight position players — all legends — have been more valuable from ages 31–38 than Beltré, who still has months remaining in his age-38 season.

But while Beltré’s bat bloomed late — maybe because he learned to swing more judiciously and stopped pressing to justify his salary — his overall performance always outstripped the way it was perceived. Even though not many noticed before this decade began, Beltré has been on a probable path to a plaque for almost his whole career. As he’s improved with age, baseball fans have wised up and belatedly begun to appreciate how great he’s always been.

Beltré, who was deemed the game’s third-best prospect by Baseball America prior to the 1998 season, made his major league debut for the Dodgers that June and went deep for the first time six days later, 84 days after his 19th birthday. Even after the early debuts of Bryce Harper and other precocious players in recent years, Beltré remains the youngest player to hit his first career homer since Robin Yount in 1974. Beltré hit only .215/.278/.369 in 77 games in that high-offense season; just by seeing significant playing time at such a young age, he marked himself as someone with great expectations. Among all now-inactive hitters since 1901 who appeared in that many games in a season in their age-19 campaign or younger, 12 of 32–37.5 percent — are in the Hall of Fame.

It didn’t take Beltré long to acclimate to the majors: The next year, at age 20, he was an average hitter with a great glove, a combination worth roughly four wins. At 21, he hit even better. He was off to a Cooperstown-caliber start.

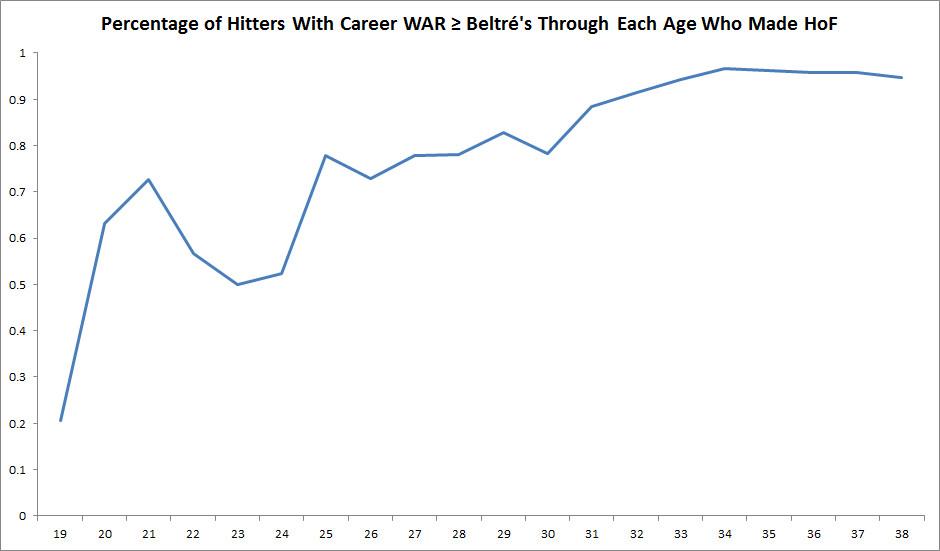

We can visualize how quickly Beltré put himself on pace for enshrinement. The graph below displays the percentage of hitters who had career WAR totals at least as high as Beltré’s at each equivalent seasonal age and who ended up making the Hall of Fame. I’ve limited the search to currently inactive players, and I’ve also made some manual adjustments, adding inevitable inductee Derek Jeter to the Hall of Fame group and excluding from the sample entirely a trio of players (Rodriguez, Andruw Jones, and Scott Rolen) whose Hall of Fame fates are uncertain and who haven’t yet been on the ballot.

If anything, this graph underrates how Hall of Fame–worthy Beltré has been, since the sample of hitters who did match Beltré’s performance at various ages but haven’t made the Hall includes players such as Shoeless Joe Jackson and Barry Bonds (whose inductions have been banned or delayed for off-the-field reasons), as well as Vladimir Guerrero, who came close to induction in his first year on the ballot and will likely join the Hall of Fame sample soon.

Even so, it’s obvious that while Beltré’s Cooperstown case crystallized in his 30s, his combination of early appearance and early performance made him more likely to make the Hall than not throughout his 20s. Even during his dip in production from ages 22–24 — which likely stemmed at least in part from a botched emergency appendectomy in early 2001 that led to an open wound and a second surgery, forced Beltré to wear an abdominal bag and an IV port, and caused an accumulation of scar tissue that continued to bother him more than a decade later — his yearly career WAR totals never made him worse than a 50–50 shot to enter the sport’s inner circle. And after his huge age-25 season — a 48-homer career year that earned him a five-year, $64 million free-agent deal from the Mariners, which raised expectations and hung over his head as he failed to replicate that power output — his WAR-derived odds never dropped below 70 percent.

Of course, WAR wasn’t available when Beltré debuted. Twenty years into his tenure in the majors, he’s been around long enough that baseball’s analytical landscape has transformed around him. Beltré made the majors months after Billy Beane took over as A’s GM and years before Michael Lewis caught wind of Beane’s success. It was an era of RBI and batting average, errors and assists. Almost no one was equipped to recognize or celebrate many of the things a young Beltré did well — walk, showcase great range, and produce at the plate in parks that weren’t conducive to sexy slash lines. Baseball Prospectus’ personal park factors show that the combination of parks that Beltré played in suppressed offense in all but one of his first 12 seasons, but few fans had heard of park factors at the time. And when at long last sabermetrics reached the mainstream, it de-emphasized fielding before it gave defense its due.

With the data at our disposal today, we can say with some confidence that Beltré has saved more runs in the field than any third baseman not named Brooks Robinson. We can point to those park factors for past seasons — and since Beltré’s ballparks have only helped him in every season since he left Seattle, his recent stats are more eye-catching for fans who haven’t developed the habit of looking at park-adjusted performance. And as the sport’s stats have caught up to Beltré’s ever-present skills, he’s evolved some soft ones that we still can’t quantify, becoming a team leader — an informal-but-real role that not only adds value but also earns him extra credit even among fans who aren’t inclined to look at his Defensive Runs Saved.

As both Beltré’s performance and the stats with which we assess it have matured, he’s more often had the spotlight on him for reasons that have little to do with his own play. First, he’s played for better teams, making four of his five career trips to the postseason during his six full seasons in Texas. (His playoff record is mostly undistinguished, although he hit well in his one World Series, for the losing side.) And secondly, social media has made him a sentimental favorite as well as a statistical star, capturing and preserving endearing idiosyncrasies — an aversion to head-touching, his pop-up-catching war with comedic sidekick Elvis Andrus, his home-run-launching look from one knee — that otherwise might have been overlooked on a national level. Only Adrián Beltré could make "torn testicle" a funny phrase.

So when did the world wake up to Beltré’s greatness? Google results for pro–Beltré Hall of Fame arguments are almost nonexistent before 2011. In early 2011, Beltré appeared on a Bleacher Report list of "The 25 Best Current Players With No Shot at Cooperstown." (He ranked 11th, four spots behind, yes, Clay Buchholz.) By late 2011, the Rangers blog Lone Star Ball paid Beltré the modest compliment of observing that "he’s going to have the sort of counting stats that could make for an interesting Hall of Fame debate down the road." By mid-2012, another Bleacher Report list allowed that Beltré might be one of the next 50 Hall of Famers, and a now-defunct blog called Three Up, Three Down declared "He’s in." And by mid-2013, reputable sources such as Sports Illustrated, ESPN, and The Hardball Times were endorsing Beltré’s case, although they weren’t treating his induction as a foregone conclusion. The turning point, then, was 2013, when a 34-year-old Beltré led the majors in hits and recorded his fourth consecutive season of 5.5 WAR or more.

I mentioned that pro–Beltré Hall of Fame arguments — or, for that matter, Hall of Fame arguments that mentioned Beltré at all — were almost unheard of before 2011. But there was at least one exception: this thread at the Baseball Fever forum, which originated on April 8, 2006. "I realize this may be a bit premature, but I was discussing Adrian Beltre with a few friends of mine," began the first post, submitted by a user named "Sockeye" who went on to estimate Beltré’s final numbers: 3,085 games, 3,033 hits, 456 homers. (Not bad, Sockeye.) The poster also put up a poll about Beltré’s Hall of Fame chances.

Most of the first-page responders weren’t swayed. "Have you ever seen Beltre play?" asked one. "As a Mariner’s [sic] fan I’ve got [sic] to see alot [sic] of him recently and I want a refund. One fluke year hasn’t set him on the road to Cooperstown." Another noted, "Not going to the hall." Someone with a Paul O’Neill avatar said, "I think Beltre has about as much chance of making the Hall as Rico Brogna." And below that, another commenter who referred to Beltré’s "fluke year" added, "Beltre doesnt [sic] stand a chance."

Beltré is still going, and so is the thread, which now stretches to 51 pages. The most recent comment dates from July 10. "5,000 total bases from a third baseman?" it says. "Lock him in."