When the future of the internet was threatened, websites used to go dark. It happened in 1996, when Yahoo and thousands of other sites blacked out their homepages in protest of proposed antiporn legislation that could have censored the broader web. It happened again in 2012, when Wikipedia was inaccessible for 24 hours as a political statement against the Stop Online Piracy Act, an overbroad proposed copyright-protection law that was about to be passed by Congress but was dropped in the face of the opposition. Today, with multiple billion-user platforms online, it’s easier than ever to beam an important message to internet users simultaneously.

But something has changed about the nature of online activism, as evidenced by Wednesday’s Day of Action to Save Net Neutrality. The web-wide event, organized by the internet advocacy group Fight for the Future, was meant to rally citizens against the Federal Communications Commission’s plans to roll back the rules protecting net neutrality, the principle that all types of data online should be delivered equally by internet service providers. The FCC is accepting public comments on its net neutrality rollback plan until July 17. Fight for the Future and dozens of major internet firms are encouraging their users to comment on the FCC’s website, sign petitions, or call their representatives to voice their support for net neutrality.

Websites are employing different tactics to raise awareness about the issue, which used to be bipartisan but now cuts along traditional political lines (Obama-appointed FCC chairman Tom Wheeler enacted strong net neutrality rules; Trump’s pick, Ajit Pai, plans to undo them.) Reddit put a pop-up box on its homepage featuring a slowly loading policy message to imitate an online future with slow and fast internet lanes. Twitter turned #NetNeutrality into a daylong trending topic. Mozilla broadcast an hourlong Facebook livestream of one of its staffers reading pro-net-neutrality comments in the dulcet tones of a late-night radio host. Urban Dictionary’s word of the day is “net neutrality,” originally defined by Cam!!!!!111oneoneone! in 2006 (yesterday’s word was “Side Daddy”). Medium, The Ringer’s publishing platform, has an unobtrusive red banner at the top of some pages (not on The Ringer, but elsewhere) leading users to read more about protecting net neutrality.

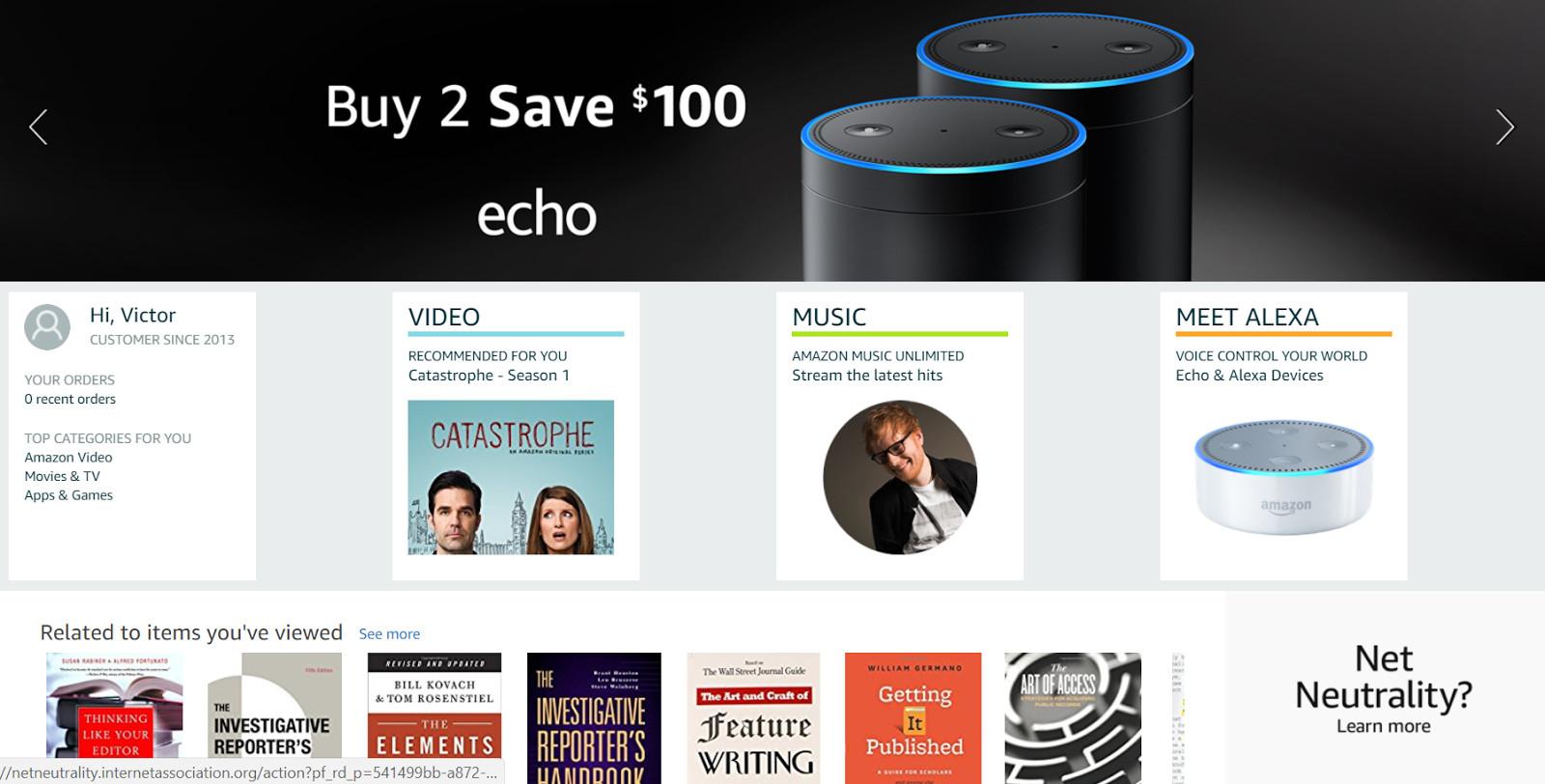

And yet many of the biggest consumer tech firms of our time, the ones with the clout to reach people who have not been engaged with the net-neutrality debate, are doing considerably less than they could (and have done in the past) to keep this issue top of mind. Google has a short blog post defending net neutrality, but its most valuable agenda-setting real estate, the Doodle on Google.com, is celebrating designer Eiko Ishioka’s 79th birthday. Facebook, which has offered custom photo filters for political causes like gay marriage in the past, relegated its net-neutrality advocacy to personal posts by Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg. Spotify is displaying a small banner urging visitors to “fight to save net neutrality,” but it appears to be on only Spotify.com, not the music app. Netflix, which positioned itself as a bleeding-heart defender of net neutrality three years ago, has an unobtrusive banner on its web client that doesn’t appear to extend to its TV apps, where most Netflix viewing actually happens. Amazon has an embarrassingly bland ad stuck below the fold on its homepage that simply reads, “Net Neutrality? Learn more.”

These actions read less like protests and more like public service announcements. An effective protest has a sense of urgency about its mission and is disruptive to both the protestor and the person affected by the action. Wikipedia going dark for a day in 2012 was the digital equivalent of shutting down an interstate highway — whether you cared about net neutrality or not, your daily routine was likely affected. But today internet companies seem unwilling to do anything that might materially affect the user experience and force people to pay attention. And in some cases they even seem to be unwilling to create the type of eye-catching content that might persuade a user to want to learn more about a sleep-inducing topic like net neutrality. There is no prosperous internet company in 2017 that really thinks a banner ad is going to sway public opinion.

Such timidity is unfortunate right now, given that net neutrality is already struggling to compete for attention with health care, Russian election interference, and a variety of other controversies in Washington. Perhaps tech giants don’t want to be accused of “playing politics” in these divisive times by passionately speaking out against a Trump appointee’s plan. But my hunch is that many of them have simply outgrown the need for net neutrality’s protections, so they’re comfortable paying lip service to the concept without getting particularly invested in the fight. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings said as much when asked why his company is less vocal on the topic compared to the last go-round in 2014. “It’s not narrowly important to us because we’re big enough to get the deals we want,” he admitted in May.

We live in an era of massive real-world political demonstrations that have seen their impact significantly magnified by the internet. It’s ironic that the companies creating the tools to amplify political voices aren’t doing more to ensure those voices will be protected in the future. Here’s hoping tech firms find their crusading spirit again before it’s too late.