Last Thursday, the Chicago Cubs sent struggling outfielder Kyle Schwarber down to Triple-A Iowa, a transaction both GM Jed Hoyer and manager Joe Maddon explained by using the word “reset.” That’s a good word to use, because through the first three months of 2017, Schwarber’s hit like a computer that has too many background processes running: .171/.295/.378, good for a 76 OPS+. Strictly from an offensive production standpoint, it’s not as bad as it looks, but for a player like Schwarber, who not only needs his bat to cover enormous deficiencies in the field, but also was supposed to play a key role in Chicago’s title defense, it’s not good enough.

So here we are, at the “Have you tried turning it off and turning it back on again?” part of the Schwarber reconstruction.

Sending Schwarber to Iowa is the equivalent of rebooting him. He’ll have a chance to get back into a groove against inferior pitching, in a league where winning doesn’t matter, and in the relative quiet of a state where only Moonlight Graham and Yasiel Puig have ever had a good time. If Schwarber’s timing or mechanics or even his confidence is off, playing every day in Iowa will give him a chance to fix the problem without hurting the Cubs, who are 1.5 games back of Milwaukee in the NL Central.

Still, it’s shocking. Schwarber was very good as a rookie in 2015: a 130 OPS+ in 273 plate appearances at age 22. Since 2001, there have been 27 seasons in which a player aged 22 or younger posted a 130 OPS+ or better in at least 200 PA. Mike Trout shows up on that list three times, and Bryce Harper, Albert Pujols, The Mighty Giancarlo Stanton, and Carlos Correa all show up twice. Assuming that the book’s still out on Schwarber and Maikel Franco, the worst player on the list is probably Austin Kearns, who still had a 12-year big league career. Then, Schwarber became the Millennial Kirk Gibson by hitting .412 on one leg in the World Series after he’d missed the previous six months with a torn ACL, the result of a gruesome outfield collision with Dexter Fowler.

It’s a little weird to say this about a player whose young career has already produced so much intrigue, but both the causes and long-term effects of Schwarber’s slump might not be as dramatic as many have feared.

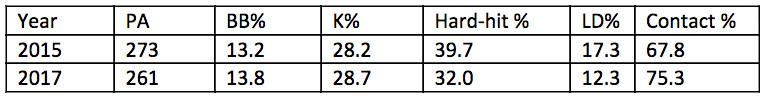

Here is a selection of Schwarber’s 2015 and 2017 stats, all from FanGraphs.

There isn’t much difference, but he’s making more contact and not hitting the ball as hard. Ben Lindbergh wrote earlier this year about how a similar change in Mookie Betts’s game made last year’s MVP runner-up a worse player during his long strikeout-less streak, but the short version is that unless you’re a young Albert Pujols, there’s a trade-off between power and contact rate. Perhaps something similar is going on with Schwarber.

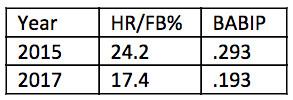

His BABIP and HR/FB% rates seem to bear that out.

In 2015, Schwarber was tied for 11th out of 352 players with 200 or more PA in HR/FB%. Some of that has to do with being a stereotype of a beefy Midwesterner and playing your home games at Wrigley, where the wind is strong and the outfield walls are about seven feet from home plate, but it’s possible he was also getting lucky. This year he’s 67th in HR/FB% out of 211 players with 200 or more PA. Luck factors into the BABIP drop as well — as a fly ball hitter who can’t outrun continental drift, Schwarber is never going to be a high-BABIP guy, but nobody’s true talent BABIP is that low. That’s not exaggeration, either. Only three times since 1901 has a qualified hitter posted a sub-.200 BABIP, and if Schwarber got to 502 plate appearances with a BABIP of .193, his would be the lowest in major league history.

It’s also entirely possible that we’ve been overrating Schwarber as a prospect. I’m as guilty as anyone, riding the Schwarber hype train since he was a college sophomore, but maybe expectations for Schwarber have always been at least somewhat unrealistic.

A year after being selected fourth overall, Schwarber arrived in the majors in the heat of a pennant race, as a power hitter with a distinctive name and body, playing for a big-market team that gets enormous media attention. In many respects, the circumstances surrounding Schwarber were similar to those that precipitated Puigmania in 2013. Fun young players on good teams just get more attention. I bet you didn’t know Maikel Franco had pretty much the same rookie season in 2015 for the Phillies; Michael Conforto — who went six spots after Schwarber in the 2014 draft, came up the same year and put up the same OPS+ in 194 PA, and also played for playoff teams in a huge city in his first two seasons in the big leagues — is nowhere near as big a name as Schwarber, despite hitting like an MVP for the first three months of 2017.

That list of players with a 130 OPS+ at age 22 or younger also suggests that a lot of the public perception of Schwarber is based on a certain perspective. Schwarber was on the very low end of that query for plate appearances and OPS+, and on the very high end of it for age. If you look for seasons of an OPS+ between 115 and 145, from players age 21 to 24, you get 146 seasons since 2001. Harper and Betts are on that list, as are Anthony Rizzo, Chris Davis, Robinson Canó, and a couple of dozen other really good big league hitters. But so are Stephen Drew, Mark Teahen, Wily Mo Peña, Jonny Gomes, and Elijah Dukes. It could be that this list, rather than the first, provides a more complete picture of the risks surrounding Schwarber. It’s not like he has a huge big league track record: We’re talking about someone with fewer career hits than Cole Hamels, and those five World Series games don’t even come close to counting as generalizable.

Schwarber entered this season as a World Series hero who essentially had half of a 40-homer season at age 22, but he was also a career .242 hitter coming off a catastrophic knee injury that had limited him to 25 meaningful plate appearances in the previous 17 months. Both of those are true, and the second makes his current season far less shocking, even if looking at it that way now feels like revisionist history.

While we should all probably lower our expectations for the rest of his career, Schwarber is still strong enough to squat a public library and still has one of the best batting eyes and hitting approaches I’ve ever seen on a player his age. It would be shocking if he didn’t have a long and productive career.

So where do we go from here?

Since 2001, there have been 18 seasons, including Schwarber’s 2017, in which a first baseman or corner outfielder, age 25 or younger, has posted an OPS+ of 80 or less in 200 plate appearances or more. Not all of those cases are instructive: Chris Burke and Tyler Goeddel aren’t really corner outfielders, but played there due to team needs; Carl Crawford has a position and nothing else in common with Schwarber; Oscar Taveras died in a car accident after his rookie year; and Jeff Francoeur isn’t really a useful precedent for anything.

Some of these players, like Joe Borchard, Jonathan Singleton, and Travis Snider (who appears twice), were huge names as prospects but never learned how to hit big league pitching. Others, like Carlos Quentin, Kendrys Morales, and Adam Lind, might sound underwhelming as potential career outcomes for Schwarber, but all of them had lengthy careers that included at least 150 career home runs and at least one season good enough to get MVP votes. You can do worse.

Schwarber’s situation is hard to find comparables for because of how quickly he reached the major leagues and then lost nearly his entire second season after a great rookie year. The most instructive comparison comes from another converted catcher with a serious reputation as a prospect: Wil Myers. Myers was only a third-round pick, but he was a consensus top-10 prospect the offseason before his rookie year. He posted a 131 OPS+ as a rookie in 373 plate appearances, which is important, because apart from Quentin (115 OPS+ in 191 PA), nobody else on that list of struggling young corner guys had anything resembling Schwarber’s success as a rookie.

Like Schwarber, Myers was hurt in an outfield collision his second season; he missed almost three months with a broken right wrist after running into Desmond Jennings in May 2014. Then, after being traded to the Padres, Myers needed surgery to alleviate tendinitis and bone spurs in his left wrist in 2015.

Myers struggled after returning from the initial wrist injury — he hit just .213/.263/.268 in the last six weeks of the 2014 season — but he hit just .227/.313/.354 before the injury, so we have the same basic components as the first three seasons of Schwarber’s career: An excellent rookie season at age 22, most of a season lost to injury, and an inexplicably severe slump.

The good news is that Myers has been quite good over the past three seasons. Since 2015, he’s posted a 113 OPS+, averaged 3.0 bWAR per 650 PA, made an All-Star team, and signed an $83 million contract extension. Myers is the best recent precedent for what Schwarber’s been through over the past year, and he turned out just fine.

Even though Schwarber’s struggles have tempered expectations that were initially inflated by the storybook journey of the 2015–2016 Cubs, there’s still every reason to expect that Schwarber will rediscover his hitting form and become a productive hitter once again.