Five Years Later, the Brooklyn Nets Are Building Something

When they moved from New Jersey to Brooklyn, the Nets tried to buy the fandom of New York basketball fans with big names and a flashy arena. That didn’t go so well. Now, they are laying a foundation the old-fashioned way: brick by brick.

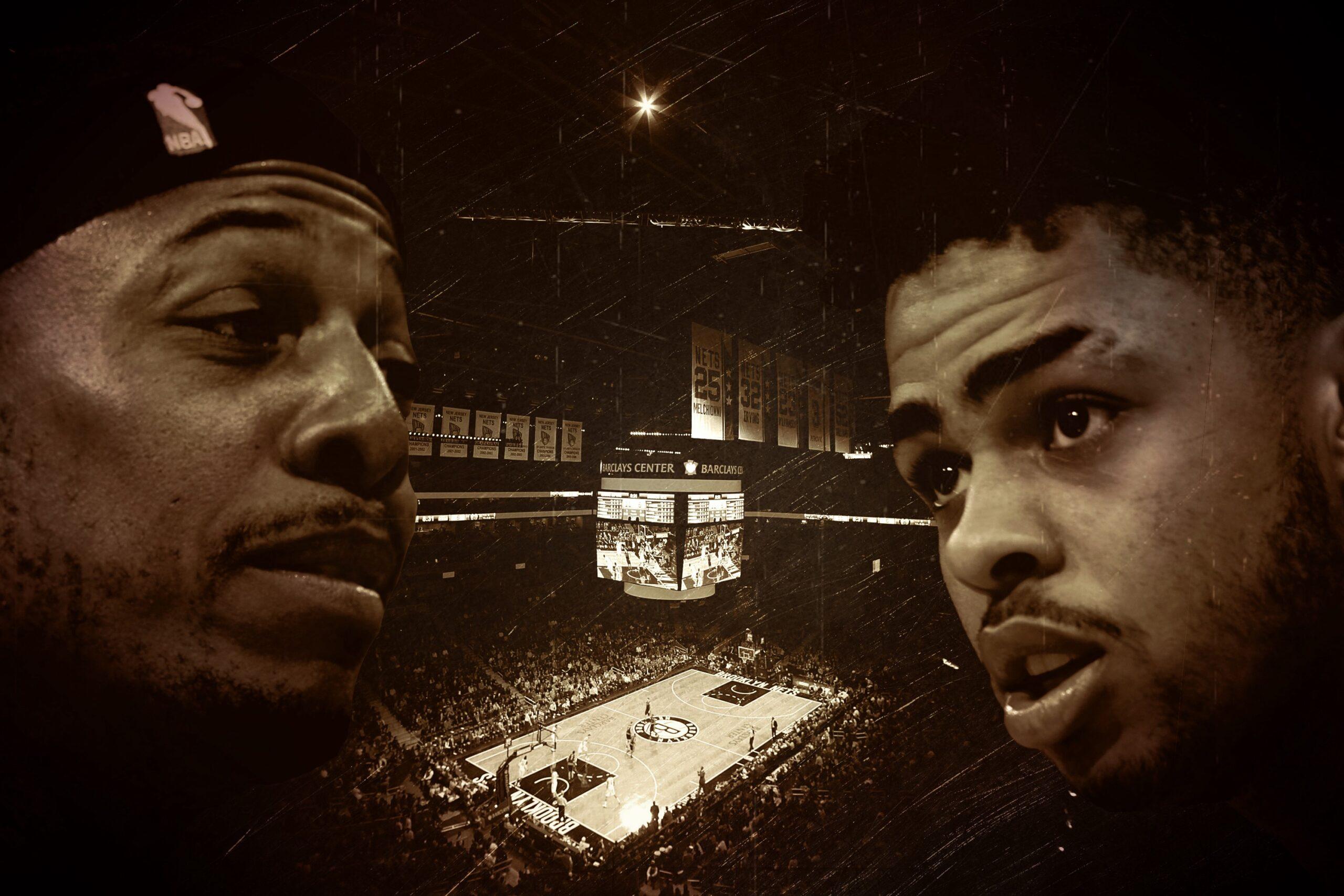

The 2017 NBA draft should have been the greatest moment in the short, awkward history of the Brooklyn Nets. The Nets suffered the worst record in the NBA last season, and the lottery balls came up Brooklyn. You can picture Markelle Fultz coming on stage after the Nets picked him first, smile brimming beneath his new Brooklyn flat brim as the Barclays Center crowd goes wild.

Unfortunately, the Nets gave away the right to that pick in a 2013 trade for Kevin Garnett and Paul Pierce. We won’t truly know who won this year’s trade between the Celtics and Sixers for that top pick for years, but we certainly know who lost it: The Nets, who have been crippled by the Garnett-Pierce trade in a way few franchises have ever been affected by one move.

Even if they needed to make that trade, it’s hard to imagine they couldn’t have done it without giving up the 2017 pick. They also gave up a first-round pick in 2014, the no. 3 pick in last year’s draft, and what should be another high pick in next year’s draft, along with a slew of players. That was more than enough for the two old players they traded for. Why did they have to throw in the ability for Boston to swap for the better pick in this year’s draft? Could they truly not have pulled off the deal without that addition?

It’s not news that the trade has been a disaster for Brooklyn — we’ve known that since 2014, when Pierce left the team in free agency after just one season and Garnett’s performance made it clear he wasn’t the player he once was. But it’s still amazing to reflect on how bad it’s been. It robbed the Nets of the ability to produce a quality basketball team — they’re not just miles away from competing; they’re miles away from the Eastern Conference teams that are miles away from the Cleveland Cavaliers who seem miles away from competing with the superteam Warriors — and it’s robbed them of the ability to reap the rewards of their badness with high lottery picks. They’re probably the first team in about a decade to earn the league’s worst record without intentionally tanking — after all, they had no motivation to.

But this week, something strange happened. The Brooklyn Nets did something positive for the team’s future. They dealt Brook Lopez for D’Angelo Russell, a move the Lakers agreed to because it also allowed them to dump the horrendous contract of Timofey Mozgov on Brooklyn and clear space for several major free-agency plays next offseason. Lopez is a fine player — if you can believe it, he’s the leading scorer in franchise history — but he’s 29, and the Nets probably won’t be able to put together a contender until he’s in his mid-30s. Russell is 21 and really good.

Brooklyn will not be the big story Thursday night. But as the rest of the NBA celebrates their futures in the Nets’ home, one wonders: Will the Brooklyn Nets ever be good?

The Nets and I were supposed to start our Brooklyn lives on the same day, Nov. 1, 2012. The lease on my first apartment started that day, and the Nets were scheduled to play the Knicks in the nationally televised first game of the NBA season. Both debuts were delayed a few days when Hurricane Sandy crashed into a city not prepared at all for hurricanes, but we were both soon in our new homes.

I wanted the Nets to fail. For starters, I’m a Knicks fan, and have been my whole life. I found it crass of the masterminds behind the Brooklyn move to assume New Yorkers would be so disloyal. New York did not need a second basketball team. I wanted everybody to know that the Nets would not take the Knicks’ fan base; they would not be more attractive to free agents; they would never be more than New York’s second team.

But I also just hated the Nets in principle. I moved to Brooklyn because it was where I could afford to live in New York as a 22-year-old who was getting rejected from every full-time job I applied for. The roof in my room leaked when it rained, the elevated M train rolled loudly past the rooms we were supposed to sleep in, but we really didn’t sleep well anyway because the landlord didn’t turn on the heat in the winter and we didn’t have AC in the summer. We ate Popeyes and deli sandwiches until it got warm enough to attempt the 15-minute walk to the closest supermarket. I was an agent of gentrification, but I was also broke.

The Nets moved to Brooklyn because "Brooklyn" had become a buzzword. The Nets marketed themselves as having street cred while razing some people’s homes (and causing the collateral damage of landlords raising the rent on others) so they could build a billion-dollar arena/spaceship to generate cash for a Russian oligarch. I wanted everybody to see how evil this was, and I figured the best way was through the basketball team playing horrendously in front of unenthusiastic, weak crowds.

I got my wish.

The Nets would not have made the Garnett trade if they were still in New Jersey. But the Nets wanted legitimacy, and they wanted it right away. They wanted to steal the city from the Knicks — who, and please, believe me when I type this, won 54 games the first year the Nets played in Brooklyn. The Nets put up big billboards claiming the city. They played up the fact that New York’s coolest New Yorker, Jay-Z, had an ownership stake in the team, although they didn’t play up how tiny it was. But all this was just flash. They needed some basketball substance.

The Garnett-Pierce trade that was supposed to bring them a real basketball team was empty flash; a reckless grab at two players whose name branding far exceeded their basketball talent in the tail end of their careers. Stefan Bondy recently did an excellent breakdown of "the worst trade ever" for the New York Daily News. There was some basketball logic behind the deal — yes, they’d lose a lot of picks, but if Garnett and Pierce made the team good quickly, they’d be able to attract key free agents, and they wouldn’t even need the picks. But as Bondy writes, everything went wrong. Pierce seemed like he wanted to leave the moment he got to Brooklyn; coach Jason Kidd bickered with assistants, Deron Williams did not handle the pressure of the situation well. Owner Mikhail Prokhorov mysteriously became disinterested in the team, or at least disinterested in financing it to the extent he had when the Garnett trade was done. Pierce left; Garnett had little trade value, and the Nets were soon a husk.

The Nets have changed in the past five years. Brooklyn has never stopped changing, and I’ve changed too. I’ve bounced around the borough: I went from that first apartment to Williamsburg to this nook of a neighborhood that wasn’t quite Bushwick and wasn’t quite Bed-Stuy and now I live in Clinton Hill, or maybe Fort Greene. I was too poor to live in some neighborhoods I’ve lived in and too rich to live in others I’ve lived in.

And in those five years, I’ve met probably about five Nets fans. I’m aware, conceptually, that there are Brooklyn Nets fans — they finished 28th in attendance this year and 27th last year, but that’s unfair because Barclays is the league’s 28th-largest venue, and that’s still, like, tens of thousands of people watching the Brooklyn Nets. I know there are still plenty of fans remaining from when the team played in New Jersey — I’d suspect they account for more than half of the fan base. But I figured while living in Brooklyn, I’d meet some Brooklyn-based Brooklyn Nets fans. Maybe I’m a bad sample: My friends from work generally come from out of town and have their own fandoms; same with my friends from college who live in Brooklyn; and my friends from childhood were all Knicks fans from the start. But if the Nets’ target audience isn’t New Yorkers or people from out of town, who is it?

I remember one night in that first apartment, we watched a Knicks-Nets game and heard our neighbors cheering for the Nets through the paper-thin walls. It was fun — we tried to cheer even louder for Knicks baskets — but I don’t remember ever hearing them watch the Nets again. There’s a dude in my current building who works for the Nets, but I don’t think that counts. I don’t know any bars that fly Nets flags and turn the music off every game night so patrons can hear Ian Eagle calling the game. I see a lot of people wearing Nets hats — the Brooklyn branding has been successful, although it’s not quite as ubiquitous as the interlocking "NY" of the Yankees. And I see kids in Nets gear pretty frequently, so maybe the Nets will achieve popularity as soon as the borough is populated by adults who grew up in the Brooklyn Nets era, people who didn’t have to switch their allegiance from the Knicks.

This has all gone exactly as I had hoped. Five years into their Brooklyn tenure, the attempts to take over New York have failed. The Nets have faded to irrelevance behind a decision as misguided as the one to come to Brooklyn in the first place. Barclays Center has been a major money loser. There are no more taunting billboards. Jay-Z stopped showing up to games as soon as he was forced to sell his stake in the team to pursue his next endeavor, the Roc Nation Sports agency. Where the Nets once tried to make as much noise as possible, they’re now just a team quietly playing basketball.

And you know what? It hasn’t been that great for me. The Nets’ trip to the cellar has not made the Knicks any better — the Nets made one awful move four years ago, but the Knicks have continued to make terrible decisions as a franchise for years. Even though the Knicks outperformed the Nets this season, New York is a much bigger laughingstock than Brooklyn. I don’t want the Nets to be better than the Knicks — I don’t want anybody to be better than the Knicks, although that desire hasn’t stopped pretty much everybody from doing it all the time — but the Nets sucking has not made being a Knicks fan more fun. Just more boring.

I’ve realized that in spite of the Nets’ ineptitude, the team isn’t going anywhere. They’ve had, quite frankly, a terrible start to their existence. But they’re not going to pack up and leave. Barclays cost $1 billion to build — they’re not going to deconstruct it and build publicly subsidized sub-market price apartments because the basketball team had some bad seasons. No, even as the team has struggled, the Nets have strengthened their roots in New York, buying a G-League (formerly known as the D-League) team and paying to renovate Nassau Coliseum on Long Island to house it.

As the eyes of the NBA turn toward the Nets’ building on this draft day, I think it’s important we look at these two trades — the one that wrecked the Nets, and the one they made Tuesday to attempt to salvage the franchise. The one four years ago sought instant gratification. It was a reckless grab at legitimacy, seizing at the first opportunity Brooklyn had to attain players with star power without regard to their present playing capabilities or the team’s future.

But this one is a really impressive, tactful move. In the middle of a half-decade draft pick drought, GM Sean Marks somehow managed to land one of the best players from the past few drafts. He took on an ugly contract, one that will hinder the team’s ability to put together useful squads until it expires. But the Nets probably aren’t going to be meaningfully good until it expires anyway.

The Brooklyn Nets swung and missed on the first few years of their existence. Instead of taking over the city, they retreated into basketball irrelevance, failing to make significant headway into the market they sought to win. But I think the Russell trade marks a turnaround moment.

I don’t know if Russell will lead the Nets to success. But I do think that the logic behind the trade for him reveals a drastically different approach to life than the one that dragged the Nets down. Even if he isn’t the player that makes them good, the idea of building something rather than scrambling for instant supremacy is a wise one.

The Nets haven’t won the city yet, but what they didn’t realize was that they didn’t need to overnight. If you told me in 2012 that five years down the road, the Nets wouldn’t have built a fan base to rival the Knicks’, I would’ve said it was proof that New Yorkers truly are loyal and we never needed or wanted a team in Brooklyn. But it’s probably just because the team has sucked. And if the Nets keep the mind-set that brought them Russell, I suspect I’ll start meeting Nets fans pretty soon.

(Especially if the freakin’ Knicks trade Kristaps Porzingis. Jesus Christ, what the hell are they thinking?)