Flashiness implies waste or distraction, but also inventiveness and charm. To be flashy is to be vain, obsessed with image. To be flashy is to expand definitions of what is acceptable, to surprise and captivate, but also to have one eye off the ball, to chase ghosts, to willingly pursue conflict and disorganization. To be flashy is to be imperfect in the pursuit of some kind of grander imperfection. To be flashy is to be like James Harden.

It should come as no surprise that Harden’s play is divisive. It’s a microcosm of a larger debate about the purpose of basketball: Is the point of playing the game to display the limits of athletic ability or to cut away distractions in the pursuit of winning? Of course, if we learned anything during this season’s MVP race and playoff push, it’s that there is an ear-shattering dissonance about what is pleasing and what is abhorrent. We agree about very little. Generally, everybody’s preferences fall somewhere in between the Spurs and Russell Westbrook, the opposite ends of this basketball perceptual spectrum: the system and the individual, the efficient and the artistic, the pragmatic and the romantic.

But these arguments coat over the best part of basketball: confusion. Our lack of agreement or understanding of what makes the NBA pleasing is what makes it so perpetually satisfying. There are plenty of factors pushing and pulling each other to create or ruin the ideal basketball game (home allegiances or vendettas, referees, players and coaches in their roles as celebrities, etc.), but from a neutral perspective, it seems that finding or disputing ideal basketball has to do with determining the balance between individual and team value and competitive and aesthetic value.

This tug-of-war is something that sponsors noticed a long time ago: Adidas released a commercial late last year for Harden’s first signature shoe. The ad opens with Harden holding the ball outside the 3-point line, being guarded by an anonymous Cavalier. The scene is paused, and the camera closes in on Harden’s profile. He looks the viewer in the eye and asks, "What if I gave you what you wanted … you know, stopped being creative?"

The rest of the commercial explores Harden’s quirky aesthetic: His pregame attire changes from a collection of high-fashion items to a white polo and cargo shorts, he asks if the Eurostep should be sent back to Europe and we see an Italian man in a suit gesturing over a crate presumably containing the move. "Want me to put my game in a box?" he asks while smushed inside a transparent cube. Here, the message is clear and unsurprising: Adidas thinks Harden’s beard and his syncopated cuts to the rim are fun, and so should you. He is visually dynamic, and that’s why you’re going to buy his shoes.

Of course the underlying conflict of the commercial, the reason that it isn’t something more simple, like Michael Jordan flying toward a sky-high rim, is that Harden’s cultural identity is markedly split. Half of his relevance is determined by his explosive creativity, the other half by his superfluity and the noise made by his detractors.

You don’t have to look hard to find somebody who believes Harden’s style to be ornamental or unfair. Evidence of his sporting sins is not rare. The most obvious example is Harden’s ability to get to the free throw line, the oft-repeated ugliest part of his game. When he has the ball, he is the Road Runner, his upper body fixed forward as his legs whirl below him, turning around defenders and opening lanes to the hoop. But on occasion, when his defender manages to hold his ground, Harden leaps and snaps his head back regardless of contact. The catch behind this move is that it is, in fact, "creative." It’s the exploitation of an inefficiency; it is competitively beautiful. For most, this is not in the spirit of the game, but Harden shot over 90 percent on 73 attempts from the stripe against the Thunder in the first round of the playoffs, so even his bad-faith acting is bewitching in the eyes of a pragmatist.

Even so, there have been other knocks against Harden: that he’s a stats-first player with little record of success. But Harden’s point guard transformation, and the success of the Rockets as a unit, has made life more difficult for those who argue that his game is all excess. The case that Harden is an unrepentant volume scorer on an irrelevant squad was easy to make when he was an average passer on a Houston team clinging to the edge of the playoff picture. It’s a tougher case to make when he leads the league in assists on a title contender.

In this Rockets offense, Harden can melt and contort the dimensions of an entire arena. His baroque movement is gasp-worthy. But sometimes he travels, and there is no whistle. He led the league in turnovers during the regular season, but without him, Houston is barely a playoff team. All of these abstract and concrete truths exist simultaneously, swirling and crescendoing, ensuring that we see different things in Harden the Rorschach Test.

To somewhat illustrate what I mean: Basketball is the midpoint between large-team and individual sports. Because five-man units are so small, and the field of play in a basketball game is so condensed, we are presented with a game that can be nearly, but never completely, controlled by one athlete. Our desire to see a player take control, like Devin Booker exploding for 70 points or Kawhi Leonard scoring 21 of his team’s last 25 points during a tight playoff game, can overshadow the end result (both the Suns and the Spurs lost). In basketball, as opposed to swimming or football, a loss can double as a masterpiece.

In the basketball world, we rarely speak directly about the importance of playing the game beautifully, as opposed to playing it well. In tennis, Richard Gasquet, a wholly mediocre player, is often talked about as having the most beautiful backhand in the game. In soccer, it is common to hear fans, players, and managers preaching the merits of beautiful play, as something separate from, or superior to, winning play. We know there is a simple, visceral appeal to athletics, but in this arena, we often don’t care to look straight at it. "Beauty is not the goal of competitive sports, but high-level sports are a prime venue for the expression of human beauty," David Foster Wallace wrote in his legendary essay on Roger Federer. "The relation is roughly that of courage to war."

Here at The Ringer, we constantly have proxy discussions about what makes basketball fun or interesting or beautiful, and we often disagree. In February various staff members gave reasons why the Warriors, the league’s most competitively successful team, were boring, while our fearless leader, Sean Fennessey, rejected "the notion that making something look easy — the primal power of effortlessness, the execution of a sound plan — is considered repellent." In March Danny Chau wrote about what our MVP leanings said about our views on the idea of "value." In April many of my colleagues opined about whether Westbrook was dishonest and hurting his team to further his own legend or if he was an electrifying hero doing his best to drag a managerial dumpster fire to victory. The beauty of basketball is that all of these things can reasonably be true at the same time.

I made up my mind a long time ago that tennis is the most beautiful sport in the world. That’s because it is simple, which is not the same as being easy. The clarity of the objective in tennis is the same thing that makes it a geometric and emotional torture chamber. The ideal shot is always right there. A groundstroke smacks into the top of the net and you’ve made a fixable mistake. A defeat is the result of the same few fixable mistakes being repeated dozens of times. Assuming that one possesses the necessary physical gifts, the key to becoming a successful player is not in macro changes, but miniscule tweaks. Put less topspin on the backhand; stand a few feet closer to the baseline. Don’t fuck up this time.

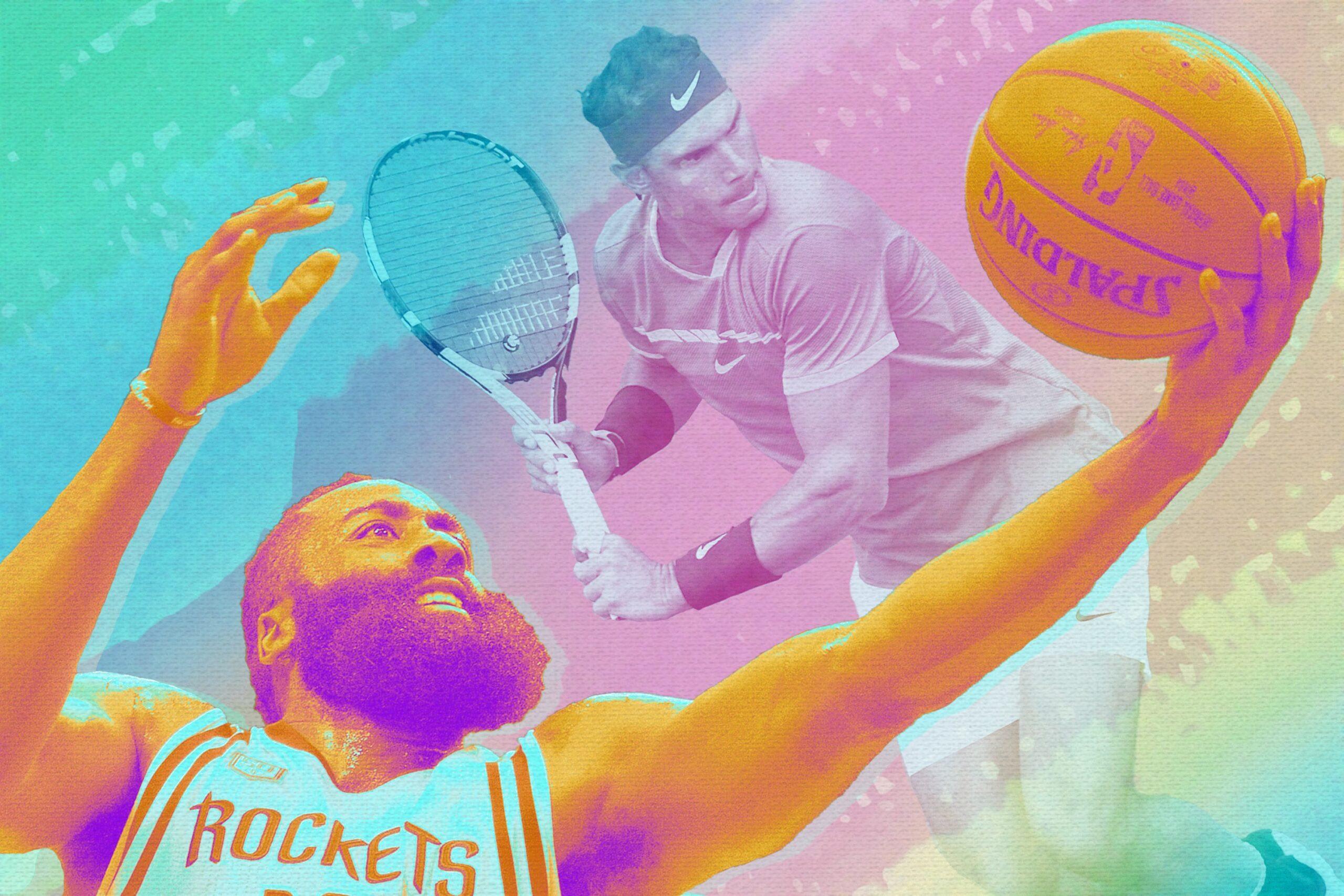

On a court, Russell Westbrook is Rafael Nadal, muscle-bound and steely eyed and determined to chase down every ball, to run himself ragged while seeing red in the midst of competition. Yet, nobody has ever suggested that Nadal’s efforts are vain. (If there is one objection to his play style, it’s that the blinders-on aggression that has allowed him to compile dozens of titles is simultaneously breaking him.) Because he is competitively successful, his pursuit is heroic. There is little to be gained from playing flashy, misguided tennis; Nadal plays this way because his incentives are singular and this is the only way he knows how to reach them. With no team to worry about, the individual will live or die only by the merits of their own abilities. Aesthetic and competitive success are one and the same. This beauty is not easy, but it is simple.

Because objectives are clear (nobody has to wonder if Serena Williams would have won 30 slams if she had gotten her teammates involved more), it follows that the athletes best equipped to navigate the game can win with remarkable consistency. And because there is consensus about who the best players are and what they ought to be doing in competition, we demand that they do it all the time.

The perpetual fetish of the tennis fan is the Grand Slam, or winning all four of the major tournaments in a calendar year. This is shorthand for having a perfect season. Since 1970, this has been accomplished only once, by Steffi Graf in 1988. For most tennis players, winning a single major is a career-justifying accomplishment and winning three majors in a single year is something that even most of the all-time greats have never done. We live in an extraordinary era for the game (for a number of reasons): Since the turn of the millennium, a tennis player has won three of the year’s four majors eight times, and each time, we yawned and asked for a timeline where they had won the fourth.

Simplicity is freeing, but also agonizing. Along with a clear ideal comes the deficiency of most outcomes. To believe that flawlessness is a possibility and to try to approach it is to be perpetually dissatisfied. This is a historically great era for tennis, and somehow it has managed, for some, to be grating.

"Perfection, it turns out, is no way to try to live. It is a child’s idea, a cartoon — this desire not to be merely good, not to do merely well, but to be faultless, to transcend everything, including the limits of yourself," Sam Anderson wrote last year for The New York Times Magazine. "It is less heroic than neurotic, and it doesn’t take much analysis to get to its ugly side: a lust for control, pseudofascist purity, self-destruction. Perfection makes you flinch at yourself, flinch at the world, flinch at any contact between the two."

The best part of basketball is that we can only vaguely understand what we want from the game. Our wildly flailing confusion is comforting. Even in an era of great parity, there is disappointment in the most successful teams and value in the seemingly mundane. Booker’s exploits on the second-worst team in the league can be magnificent.

This is a Rockets Moment: Midway through the second quarter of their Game 1 blowout of the Spurs, Lou Williams blocked a driving Tony Parker and sent Houston off to the races. Clint Capela tipped the ball to James Harden, who danced toward the hoop. When Harden got into the paint, he became the center of a whirlpool. Three defenders were carried in his direction, leaving Trevor Ariza open in the corner. Harden Eurostepped and kicked the ball to Ariza, who drained his shot while falling into the crowd.

The Houston offense is loud and bombastic and, somehow, calculated. It is a screaming Cat Anderson trumpet solo birthed from spreadsheets and stat models. It is the perfect marriage of the individual and the unit. If Steph Curry and Klay Thompson expanded the basketball court, Harden and the Rockets have done the most intricate exploration of its dimensions.

It’s not coincidental that Rockets Moments like these also double as Harden Moments. "Moreyball" and Mike D’Antoni’s schemes are obsessed with exploiting inefficiencies, but the Rockets thrive because they have Harden’s flash at their center. They saw him fighting giants on his own and gave him access to the Megazord’s cockpit. Now the Eurostep isn’t just a layup-creating mechanism, but an instrument used to clear the court. This is individual, team, competitive, and aesthetic appeal all at once.

Sunday night, the Rockets topped the Spurs to even the series at two games apiece. If a butterfly flaps its wings at the right time, they’ll find themselves in the conference finals, but in all likelihood, that’s as far as their season will go. Harden’s exploits may not be enough to carry this team to a title. Maybe D’Antoni’s system is in need of more tweaks. Maybe any version of this experiment is doomed in an era when the Warriors exist. Or maybe Houston will surprise us and win the whole damn thing. But, for now, we have plenty of time to disagree. The Rockets are still imperfect, which is beautiful.