Caroline Renee Mills loves classic British literature. The 32-year-old freelance writer adores Thomas Hardy’s 1878 Victorian novel The Return of the Native, especially for the “dark, misunderstood, moody” character Eustacia Vye. She’s a fan of nearly anything written by the Brontë sisters, particularly Jane Eyre. And her all-time favorite is Daphne du Maurier, the British romantic novelist that published stories like The Birds, Rebecca, and The Jamaica Inn that were later made into Hitchcock films.

“She was a master of suspense,” Mills told me. “She was very good at being literary but also appealed to the popular audience.”

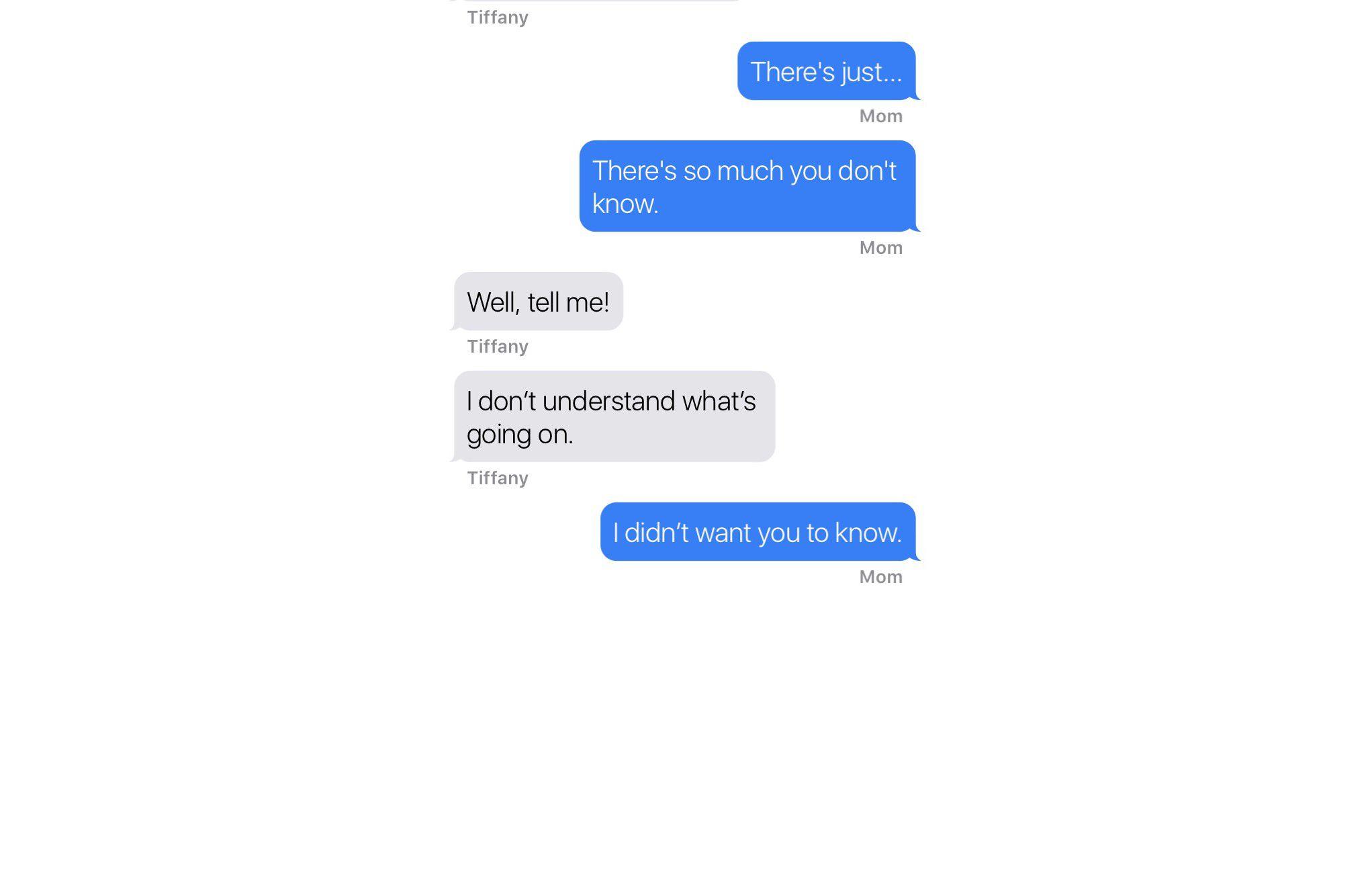

It is these qualities that Mills says she hopes to incorporate in her work — albeit in a format that would be wildly unfamiliar to Hardy, the Brontës, or du Maurier. Last month, she began writing for Hooked, an app that publishes fictional text message conversations. Her first story, “SafeHaven,” follows a chat between a therapist named Dr. Hortence Took, and her latest patient, who the reader soon learns “did something bad.” It’s not written in paragraphs or chapters, but via a stream of fragmented SMS chat bubbles called “hoots” that are split up into a series of seven separate “episodes.” Users are prompted to tap on their smartphone screen to push the conversation forward. If they tap too fast — as one often does with these stories — they’ll hit a paid-subscription wall. And aside from reading, users can also comment on the piece and follow Mills for updates. So far, Mills’s first tale has earned over 85,000 views.

“When I think about releasing things in smaller episodes, I think of Dickens,” Mills said. “His novels were released in serial publication, and not as one big chunk. That’s kind of what we do on Hooked with episodes, just to keep the suspense and keep people coming back. I find it helps with the very different attention spans nowadays.”

Since the birth of the novel, the discussion of how a story’s form influences the quality of its content has always been a charged one. Even the current Encyclopedia Britannica entry for the word snootily asserts that “despite the high example of novelists of the most profound seriousness, such as Tolstoy, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf, the term novel still, in some quarters, carries overtones of lightness and frivolity.” This long-standing debate has only been magnified in the age of the internet, as young, experimental writers have found new ways to adapt their prose to the world’s most trafficked platforms. In the mid-aughts, Japan’s best-seller list was flooded by “cellphone novels,” which were written solely on the keypad of a phone, much to the chagrin of the country’s literary elite. In 2012, author Jennifer Egan collaborated with The New Yorker to tweet out her story “Black Box” line by line — a fun stunt which other authors recreated, although reluctantly. In 2014, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick was translated into emoji and that version was later accepted into the Library of Congress. And services like Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited have pushed self-publishers to become serial content creators, often at their own expense.

And now commercial and experimental forces at play in the publishing world have combined to bring us a handful of chat-fiction apps. In its two and a half years of existence, Hooked has racked up a cool 10 million downloads, the majority of which came from females between the ages of 11 and 20, according to Adam Blacker, brand ambassador for mobile-app research firm Apptopia. Blacker also notes that, last month, Hooked brought in its highest revenue sales ever, earning approximately $550,000 via in-app subscriptions to the service. A Hooked story often stars a teen protagonist, and typically falls into the same genres that have dominated the young adult fiction market in recent years — including dystopian thrillers like The Hunger Games or Divergent, paranormal romances like Twilight — as well as horror and science-fiction.

There are plenty of reasons young adult fiction is ripe for a smartphone-centric takeover. For one, the majority of American teens now own smartphones, and — according to research from the Pew Institute — are almost constantly online. At the same time, more and more studies indicate that young adults’ interest in reading has waned. Though researchers have yet to find a link between the massive buffet of on-demand digital entertainment available online today and sagging numbers in teen reading rates, many have a hunch. “Numerous reports show the increasing use of new technology platforms by kids,” Jim Steyer, CEO and founder of the nonprofit Common Sense Media, told NPR in 2014. “It just strikes me as extremely logical that that’s a big factor.” That many YA books have been made or broken by the enthusiasm of online audiences is also an indicator. After building up a loyal online fan base on Tumblr and Twitter, author John Green’s 2012 YA novel The Fault in Our Stars topped Amazon’s best-seller lists before it was completed. And thanks to his presence on YouTube, the following movie was also a hit. “When you have the kind of regular relationship with your audience that I do, pretty much 100 percent of that built-in fan base buys your book within the first month,” he wrote on Tumblr in 2013.

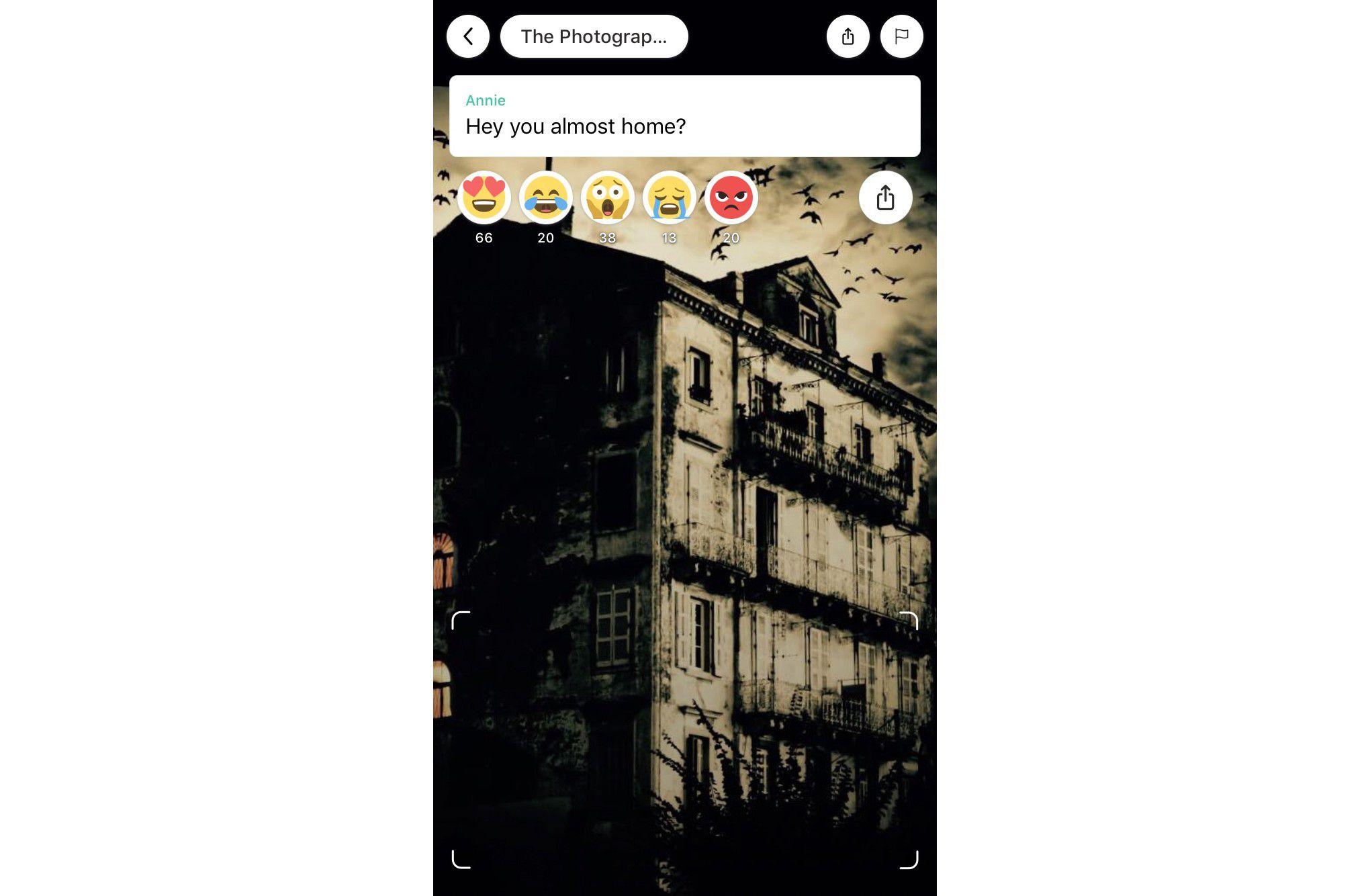

Naturally, competitors are biting at Hooked’s heels. There’s now Yarn, which publishes interactive fiction in addition to gamebooks and “text adventures” that star you, the user. (Example: “It’s your birthday today. Your ex-girlfriend brings you a present, and inside are a series of mysterious letters that tell the story of an old love triangle that ended in murder. Solve puzzles, solve the mystery, or get wasted and do neither: it’s up to you.”) And also Tap, which allows users to react to a story line-for-line using emoji. It’s no wonder that entrepreneurs are aiming to reformat concepts like Goosebumps choose-your-own-adventure books into digital formats. But with a new format comes old problems. Questions remain of how exactly these apps will compensate their writers in the age of on-demand content, and also whether tapping through a string of text messages counts as reading at all.

Prerna Gupta, who cofounded Hooked with her husband, Parag Chordia, likes to think it does. The initial idea for the app came to her three years ago in Costa Rica, as she was writing a young adult novel with her husband about an Indian girl living in Silicon Valley 100 years into the future. Midproject, she panicked. “Would anyone read a sci-fi story with a dark-skinned, female protagonist?” she asked in — you guessed it — a Medium post detailing Hooked’s origins. “How was I going to convince an agent to take a book like this seriously? Would a publisher be able to find an audience for my strange story? And, do teenagers even read?”

Her series of questions helped spark an investigation. She and her husband began to A/B test stories, pulling the first 1,000 words from 50 best-selling YA novels and loading them into a web reader to measure engagement. After running 15,000 subjects through their experiment, they were disappointed.

“We saw that teenagers were not getting very far at all when reading a best-selling novel on their phones,” Gupta told me. “So that was like, ‘OK, if books just stay where they are, they literally are dying.’ You cannot compete with Snapchat and Instagram and Facebook for a teenager’s attention on their phone with a 300-page novel written and presented in a normal style. It’s just not going to work. We’ve already lost that battle.”

The findings led Gupta and Chordia to start investigating teens’ preferences — from narrator perspective to the gender and race of a protagonist — and test formats that would encourage longer reading times. After trying out formats that resembled comic books and were filled with images, they finally took a chance on a text message design. The results were, as Gupta described it, “staggering.” Nearly every teenager who started reading the chat story finished it in one session. Four months later, she and Gupta officially launched Hooked, their half-written YA novel a distant memory.

Not everyone is psyched about the idea. “We’ve been here before!” Chad Felix wrote of Hooked in December of last year, on the blog of independent publisher Melville House. “Mad, I mean, about a developer giddily steamrolling the complex natures of books, writers, and readers alike.” Felix echoes the fears of critics that came long before him, and his is a reaction that Gupta has grown quite accustomed to.

“There are a subset of people that have a very visceral negative reaction,” she said. “That things are bad enough as it is and we’re just making things worse. It’s not real somehow, it’s not real reading, it doesn’t count. I’m not trying to destroy the novel, I’m trying to get more people to read because I don’t want it to die.”

As more developers have moved into the chat-app market, they’ve chosen to market their content not as a replacement to traditional reading, but as a way to hold your attention just like any on-demand entertainment platform. The advantage being that these stories can spark people’s interest during small moments in the day, like waiting for a train or riding the elevator, without requiring much effort.

“When we talk about competition, we often talk about how our biggest competition is people’s boredom,” said Tarun Sachdeva, the head of emerging products at Wattpad, the company that owns Tap. “We’re trying to make sure that we can capture people’s time, and give them something entertaining to fill it. We think of our competitor as not so much other folks in the book space, but anyone else that’s putting out an entertainment product. YouTube or Netflix is just as much of a competitor to us.”

A more prominent challenge for these chat apps is finding a way to adequately compensate their contributors. Sachdeva says that author compensation is still in flux at Tap. According to Gavin Hetherington, who has written 17 chat stories for the app, writers can both be commissioned to write featured projects and earn money via ad revenue generated through a type of “stars program.” Hetherington, who is studying English literature at Newcastle University and aiming to work on novels full time, says both the pace of the writing and exposure on the app have offered more benefits than Amazon’s pay system. Similarly, Mills is commissioned by Hooked editors to write pieces for an agreed-upon amount beforehand. It’s not enough to live on alone, she says, but she’s lucky be supported by her wife and her family as she pursues her ambitions of becoming a fiction writer. Hooked has yet to implement any payment models based on ad revenue, but Gupta says the system is evolving as the company grows.

“Some of that is just simplicity: We’re a startup and as soon as you get into tracking streams things get really complicated really fast,” she said. “I also think it’s nice for the writer because they know what they’re going to get ahead of time. Our writers feel it’s fair and maybe even generous because it’s not just here’s some crap advance, and then if it does well, the promise of more money.”

For both Mills and Hetherington, there is also an added benefit of experimenting with a genre that very few writers have before. In some cases, the constraints allow them to explore elements of a story like plot and character development via the rhythm of the messages, images, emoji, or the typing ellipses.

“You just start writing and it flows and it feels pretty authentic just doing it and reading though them,” Hetherington said. “And a lot of people on Tap, I’ve noticed … leave some little mistakes in because it feels like that’s how it would have went. Like, ‘Oh, someone accidentally sent that too early.’ There’s just a bit more real life to it.”

These small nods to text messaging idiosyncrasies are exactly what drew Grace Chou, a 27-year-old Bay Area resident, to pay for a Hooked subscription. Though she reads books both in paper form and on the six-inch screen of her iPhone, she sees Hooked as its own genre — one she can enjoy in brief bursts while she’s on hold or in line for lunch.

“I think part of what makes reading stories in text message format fun is that it captures emotional and cultural nuances, for example with emojis — it makes the stories more captivating and the characters more relatable, especially for millennial readers.”

Mills is encouraged by the fact that the app gets people to read at all.

“I don’t care what people are reading as long as they’re reading,” Mills said. “You could be reading the back of a shampoo bottle. I just think reading is good for mental health, it’s good for your intellectual capacity. I don’t think this means reading is dead just because it’s changing.”

An earlier version of this story referred to the character Dr. Hortence Took with a male pronoun. She is a woman. Also, this story previously misspelled the name of the “Black Box” author. Her name is Jennifer Egan, not Eagan.