Midway through the second season finale of Syfy’s The Expanse on Wednesday, a moment from a previous episode came to mind. Alex (Cas Anvar), a space-cowboy cast-off from the Martian military who talks to his ship and seems to expect it to whinny and nuzzle his neck in response, is trying to rescue his crewmates from the largest Jovian moon, Ganymede. The moon is a flashpoint in a standoff between the navies of Earth and Mars, so if Alex activates the main drive of the Rocinante, a stolen Martian attack ship, he’ll be greeted by more missile locks than a MiG pilot in Top Gun. To reach the rest of the stranded protagonists, Alex must plot an undetectable path through the effective blockade, using thruster power and gravitational assists from neighboring bodies to slingshot the ship through the system. And to do that, he has to see the whole system at once.

“Go wider,” he instructs the ship’s computer, which doesn’t go as wide as he wants. “Wider. I said wider! Show me the whole goddamn system. OK. Now, where are we, exactly?”

Standing in the center of that dizzying display, struggling to grasp his position in a vast three-dimensional space, Alex echoes how some viewers felt at the start of the series’ first season. True to its title, The Expanse’s early episodes imparted the thrill of possibility alongside a persistent, vertiginous sense of not knowing quite what was happening or who deserved our sympathies. Like the suspended space-walker in the opening credits, I floated along, feeling unmoored from some of the smaller-scale story beats but captivated by the scope of the series’ vision of a future 200 years hence, in which humanity has settled the solar system but split into three conflicting factions (Earthers, Martians, and Belters) instead of forming a Federation.

Was that cramped and squalid space rock Ceres or Eros? Why was Thomas Jane’s hardboiled Belter detective, Joe Miller, so much more interested than I was in the mysteriously missing heiress Julie Mao? Were these accents and hairstyles and jumpsuits serious? (They were, and gloriously so.) In those disorienting days, I was grateful for every bit of hand-holding the show provided — an establishing shot of a shiny new Manhattan, or the scrawls of explanatory text that accompanied each major switch in settings.

In its faster-paced second season, though, The Expanse began to feel more manageable, the way a foreign language clicks after enough time in an immersion course. The show went wider, but I knew where I was. The way forward wasn’t always direct — Miller suffers a destabilizing death partway through the second season, giving Jane time for some big-screen sci-fi — but like Alex, I could plot a path past the patrols and gravity wells. The show’s improvement in pacing crystallized a critical consensus that lent it a touch of prestige-TV luster, a rarity for SyFy (and sci-fi), although that approval didn’t translate to a rise in traditional ratings.

However, Wednesday’s second season finale, “Caliban’s War,” disrupted that recent stability, removing the perception that The Expanse’s many moving pieces of plot adhere to the same predictable, Newton’s Law–like patterns that allow Alex to plot precise orbits. The Expanse is a show that prides itself on its science, but like other genre fiction before it, it appears poised to pivot away from the realm of reality. How it handles that change will determine whether future seasons can sustain the second’s success.

Much as Game of Thrones’ fight for the Iron Throne plays out against the backdrop of a coming confrontation with an ancient, supernatural power, The Expanse’s jockeying for control of the solar system is a squabble compared to the existential threat posed by a mysterious “protomolecule,” a substance of extraterrestrial origin that glows bright blue like the Cherenkov radiation it gravitates to and absorbs. After the protomolecule infests Eros and kills (or transforms) its inhabitants, glowering do-gooder James Holden (Steven Strait) and the Rocinante crew that he loosely commands devote themselves to eradicating any trace of the substance from the system. Naturally, other parties see it as something to be studied or exploited in the pursuit of power, which sets up a higher-stakes struggle.

This week’s finale dismisses the idea that Holden’s goal is achievable. The protomolecule has always been an unknowable black hole at the center of the plot, pulling all objects toward it, but “Caliban’s War” is when The Expanse passed the event horizon. “It’s already scanned too far to ever be sure it will be gone,” Holden’s lover/crewmember Naomi (Dominique Tipper) tells him toward the end of the episode. “It’s part of the equation now. And it will be from now on. We can’t change that. We can’t wish it away.” The Expanse is no longer about destroying an intelligent, toxic material; it’s about what learning to live with it looks like.

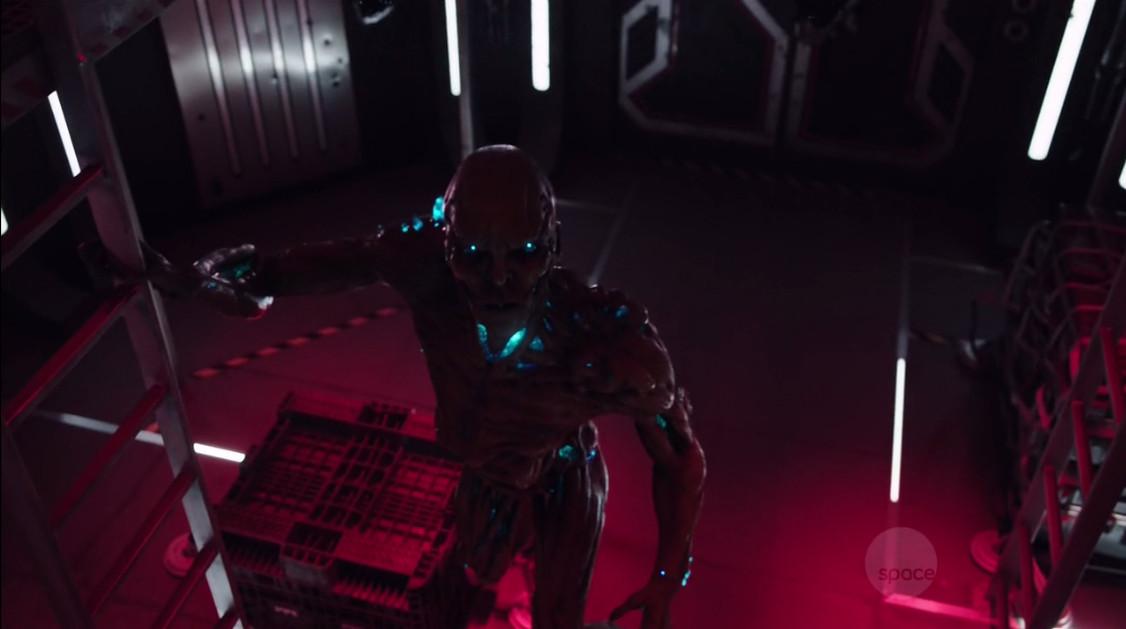

The finale derives its suspense from two standoffs, the more urgent of which pits Holden against a humanoid protomolecule monster — an X-Files-esque hybrid of human and alien. Previously glimpsed only in onscreen schematics and brief, hallucinatory in-person sightings, the monster — a cross between a figure from Bodies: The Exhibition, Pinbacker from Sunshine, and Westeros’s White Walkers — gets its closeup in “Caliban’s War.” Although Holden and Co. defeat the single stowaway, the season ends by hinting at many more hybrids to come.

The episode culminates in an almost mystical scene in which an exploratory, Adam Savage–crewed vessel descends to the surface of Venus, where the protomolecule-ridden remnants of Eros were plunged for the rest of the solar system’s safety (and believed to be incinerated). As the ship nears the crash site, the turbulence stops; suddenly, it’s stripped down to its component parts, as its crew hovers in the air, evidently unharmed. The protomolecule not only survived planetary impact and the toxic atmosphere of Venus, it seems to have evolved.

Just like that, The Expanse’s patina of scientific rigorousness is pierced, as easily as the protomolecule monster tears through the Rocinante’s hull. This is the series’ monolith moment, or maybe its version of Star Child. It’s inspiring and unsettling, and while it could end up elevating The Expanse, this kind of departure can’t come without causing an offseason full of uncertainty for viewers who haven’t read the novels from which the show is adapted.

If the protomolecule isn’t magic, it’s indistinguishable from it, a complete wild card unbound by the physics that govern everything else in The Expanse’s previous reality. The Expanse’s production design is gritty and grounded; it’s a show in which even futuristic computers have scratches on the screen. “That is the world,” book series coauthor Ty Franck told me when I talked to him last year. “It’s gleaming and high-tech and dirty and poverty-stricken all at the same time and often all in the same place, and the minute we lose track of that, that’s when it starts to feel unreal.”

If you preferred Game of Thrones when it was about beheadings and brothels more than dragons and greenseers, or Battlestar Galactica before Starbuck’s resurrection, The Expanse’s flirtation with a more fanciful foe might not be a welcome development. The Expanse is far from the first hard sci-fi or traditional fantasy series to loosen its storytelling strictures, but the inscrutable presence of François Chau in this week’s finale (playing another Pierre) reminds us that there’s some risk of running off the rails when a show strays too far from what’s plausible. Maybe Lost didn’t have to have polar bears.

Fortunately, The Expanse is laudable for more than just getting zero gravity right. Funny hairstyles notwithstanding, the show’s clever writing, strong character conceptions, and interest in asking big questions — if “no weapon ever brings peace,” as Naomi tells Holden in the finale’s second-to-last scene, one wonders what will — allow it to play on a more metaphysical field. The show is evolving, and if it’s entering a Childhood’s End or Arrival-esque phase, it will only enhance the rich sci-fi tradition of enlisting an entity from a faraway galaxy to point out the flaws in our own.