Six times last fall, on the eve of every football game that Stanford hosted in the 2016 season, Solomon Thomas and Harrison Phillips shared a room at the Crowne Plaza Cabana in Palo Alto, California. The Cardinal defensive linemen had been close since arriving on campus in 2014, and while they talked often, these nights were different. They provided a chance for the pair to wade into conversations while shut off from the rest of the world.

Sometimes the sessions were casual, a couple of kids just shooting the shit. There were other nights, though, when one of the most fraught political climates in recent American history set the stage for the two to talk about what was happening across the nation. They discussed racial inequality, police brutality, Colin Kaepernick’s protests, the formation of modern Chicago, and the lack of opportunities afforded to unprivileged youth. “Stuff like that matters to me a lot,” Thomas says. “I’m just trying to educate myself as much as possible, to try to have a better understanding and know that if I say something, I can back it up. I have my opinions, but I’m still learning.”

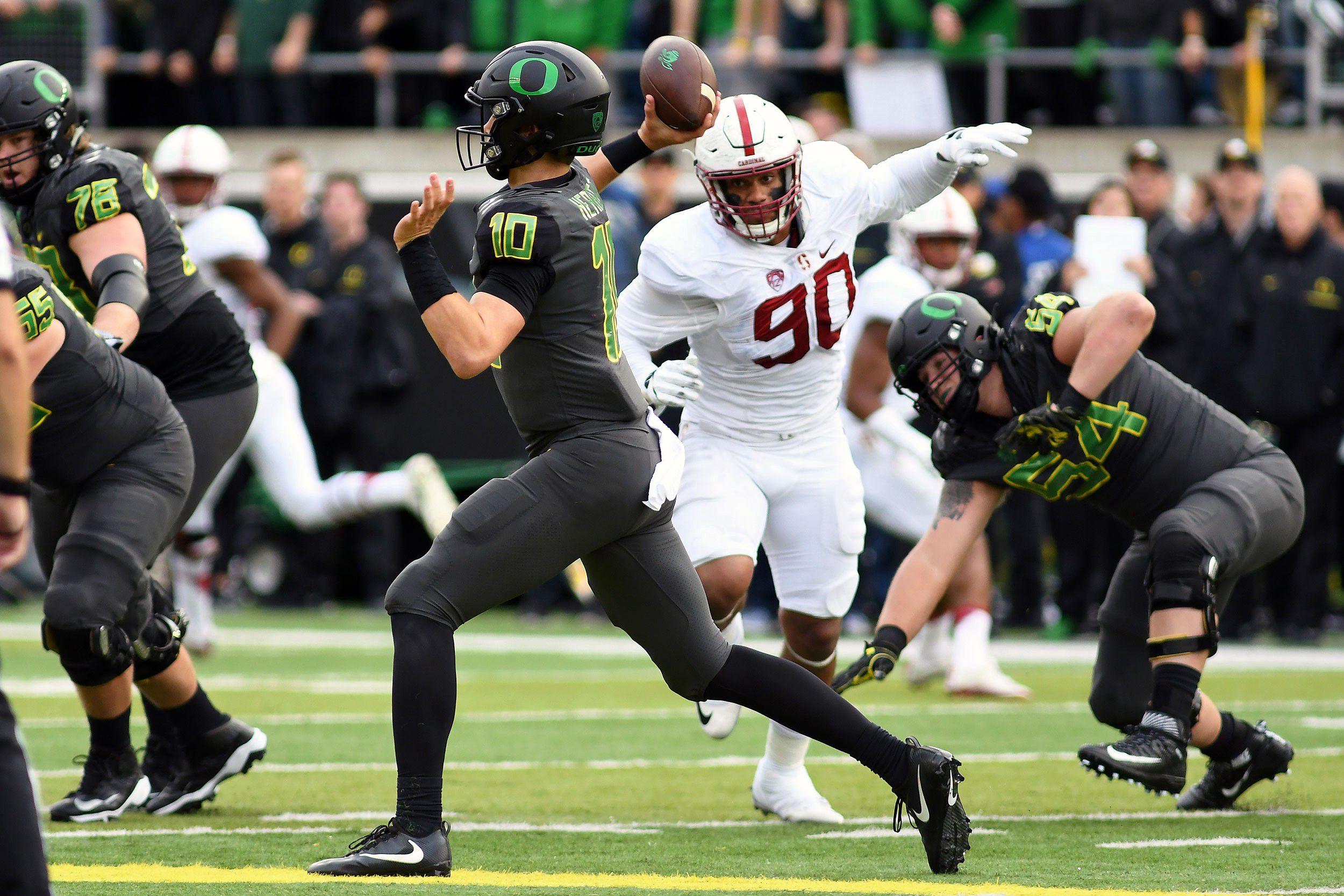

Nearly five months after the duo’s final stay at the Crowne Plaza, many of the issues facing society haven’t changed, but Thomas’s standing within that society is about to. After declaring for the NFL draft on the heels of a redshirt sophomore season in which he recorded 14 tackles for loss, including eight sacks, and earned first-team All-Pac-12 honors, Thomas has emerged as one of the most prized prospects in the 2017 class. By the end of his Cardinal career, he’d become one of the most dominant defenders in the country, and his final collegiate flourish—seven tackles (including two for loss), one sack, and the game-sealing burst into the backfield to drag down potential no. 1 pick Mitchell Trubisky in a Sun Bowl win over North Carolina—was the exclamation point on it all.

The multipurpose pass rusher, whose chiseled 6-foot-3, 273-pound frame should help him to bounce among positions along the defensive line, has been considered a potential top-five pick since the draft process began. That kind of hype is typically reserved for a budding superstar, the future face of a franchise. His jaw-dropping athleticism and versatility are coveted in the modern NFL. And for as much as Thomas’s skills should translate on the field, his curious mind and willing voice may be even better suited to propel him to a long and prosperous career in the spotlight.

“He’s a kid that always wants things to be right,” Stanford defensive line coach Diron Reynolds says. “And if ain’t right in his eyes or in his heart, he’s going to speak his mind.”

Thomas has never hesitated to be himself, even in his most public moments. After completing a stellar career at Coppell High School just north of Dallas, he held scholarship offers from many of the premier college programs in the nation, including Alabama, Clemson, Ohio State, and Oklahoma. He planned to have a commitment ceremony similar to those that many blue-chip prospects stage, only his came with a twist. “I’m not a big hat guy,” he says, referring to the custom of players declaring their college of choice by donning that school’s baseball cap. Rather than throw on a Cardinal hat, Thomas reached beneath a table to pull out a tree in a pot stamped with the Stanford logo and slipped on a pair of glasses with tape wrapped around the bridge. “[The thought was], ‘We’re going to own it,’” Thomas says. “We’re going to be Nerd Nation.’”

The gesture was fitting for Thomas, who has long been willing to let his geek flag fly. He’s been a Star Wars fanatic from a young age, and one early Halloween his mom painted his face to resemble Darth Maul’s in The Phantom Menace. “I thought it was the coolest Halloween ever,” he says. “I was trying to kill everyone with my lightsaber and use the force. I thought I could actually use it.” Upon getting to Stanford, Thomas made it his mission to convert Phillips—who’d previously never seen a film in the Star Wars canon—to the Dark Side by dragging him to the theater for his first (and Thomas’s fifth) viewing of The Force Awakens. “He needed to know,” Thomas says. “He needed to learn about the Star Wars life and how much it can change your life.”

Thomas’s willingness to speak his mind and influence others transcends small moments of self-indulgence and pop culture tastes, though. Stanford’s campus served as an incubator for Thomas, not only for his game, but also for his worldviews. The day after the United States presidential election last November, the players in the Cardinal’s defensive line meeting room stopped watching film and and had a conversation. “Not only around the country, but around the university, around the school, everywhere else, you could tell our nation was split,” Reynolds says. “And that’s one of those things, you’ve got to sit there and address your kids because people come from different social backgrounds and have different views of the world. [It’s about] just teaching each other to respect them.”

Thomas was one of several players to speak that day. He tried to communicate what he had observed growing up in Texas, where he lived for most of his adolescence. (His family lived in Australia from the time he was 5 to just before his 10th birthday.) He also made it known that he was eager to hear others’ perspectives. “I was just telling them my experiences in my life and what I’ve been through, [and also that] I’m not mad at anybody in this room for anything or what their beliefs are.”

For Thomas, the presentation of a message deserves similar consideration to the message itself. It’s an idea that he discussed at length with Phillips as it related to Kaepernick, who had been kneeling during the national anthem in protest of racial injustice just 13 miles down the road from Stanford’s campus. Thomas understands that to some, athletes—especially NFL players—vocalizing opinions about topics outside of sports can be divisive. As he prepares for the draft, he knows that striking the right balance can be complicated. “I try to have a purpose—every tweet I have, every Instagram post, anything I say to the media,” Thomas says. “I want to have purpose in what I say and getting my message across.”

Take a lap through Thomas’s Twitter feed, and you’ll see very little original material. Nearly his entire timeline consists of retweets; much of it, particularly of late, has related to his Stanford teammates and the draft. Yet during the final days of Barack Obama’s presidency in January, most of Thomas’s presence on the site had to do with the commander in chief. On the day after Donald Trump was elected, Thomas shared a combination of resilient thoughts and growing concern from the likes of Hillary Clinton, David Axelrod, and CNN’s Van Jones. “I don’t tweet that much because sometimes when you tweet, you can tweet too fast,” Thomas says. “When I tweet, sometimes I can’t get everything I want to get across in 140 characters, so I’ll use like five retweets to kind of form what I’m feeling.”

Thomas’s online persona is carefully curated in part because of how much he values his growing influence, and how he believes he can use it to become a positive force for whichever team drafts him. But he doesn’t think having a platform alone should create pressure for athletes to be socially or politically outspoken. “I don’t think they have an obligation,” Thomas says. “I think they have the opportunity.

“I don’t think every athlete has to give his stance on what’s going in the world. But if they’re educated and ready to get a critical response to it, I feel like they should. If they want to engage in the conversation and educate others, I think they should.”

A consistent presence in Thomas’s retweets is Seattle Seahawks defensive end Michael Bennett. Whether Thomas recirculates a simple line or a television appearance during which Bennett espouses his views on athletes away from the field, it’s clear that he views the Pro Bowler as a role model. “I respect what he’s doing and what other athletes like him are doing: showing other people that, you know, we’re not just football players,” Thomas says. “We’re people. We have a big, beautiful brain as well. We’re not just dummies that go out and entertain people.”

In Bennett, Thomas sees a worthwhile mold for himself as a voice in the athletic community, but that isn’t where the comparisons end. The most pressing question about Thomas’s pro potential is which position he’s best suited for in the NFL. At Stanford, Thomas did almost all of his work lined up inside the offensive tackle. He could often be seen jarring an opposing lineman with a vicious punch, controlling that individual blocker as a way to keep him away from his defensive teammates on the second level, and diagnosing the play as it unfolded.

At 273 pounds, Thomas is considered undersized for an interior, two-gapping role in the NFL, but even if he did have a little more bulk, that spot wouldn’t be the most effective one from which to deploy a player with his physical gifts. Thomas put on a show at this March’s combine; his movement and explosion scores ranked in at least the 74th percentile among defensive ends and aligned with the suddenness he showed on tape last season. Using a pass rusher with that type of burst to eat up space would be a crime against both humanity and football.

Thomas’s future is as a one-gap penetrator. To pinpoint the best possible path for him, look no further than the bearded Seahawks star who populates his Twitter feed. Bennett is an inch taller than Thomas, but they have similar builds. (Bennett is 6-foot-4, 274 pounds.) Due to his size and run-defending prowess, Seattle uses Bennett as its left defensive end in base packages and as an interior pass rusher on nickel downs. Rather than seeing his tweener status as a detriment, the Seahawks understand that Bennett’s build gives him a chance to fill two different roles within their scheme. Thomas hopes that teams look at him as a similarly malleable piece. “When you draft me, you’re not getting one type of player. I can own one of the player types and morph into it, or I can be all that you want me to be. I can play from the 3-tech to a 9-tech,” Thomas says, alluding to his ability to line up anywhere from a penetrating defensive tackle to an end situated out wide.

Wreaking havoc in the backfield as a one-gap player is ingrained in Thomas’s DNA. Reynolds says that in 2014, when he worked as the assistant to legendary Stanford defensive line coach Randy Hart, the challenge with Thomas was getting his grasp of the position’s nuances to match his otherworldly burst. “It was just trying to get the techniques to catch up with his speed,” Reynolds says. “He would go and do things too fast but not with the right technique.”

At the beginning of Thomas’s career, that meant taking a step backward before he could take five steps forward. Weighing only 245 pounds, he initially lacked the bulk to get on the field for the Cardinal, and he spent his first on-campus season on the scout team. Playing against future first-round picks Joshua Garnett (now with the 49ers) and Andrus Peat (Saints) and Stanford’s smashmouth offense each day in practice, Thomas shaped his game around understanding the finer elements of run defense rather than relying solely on his explosion. “Any time you have those bodies coming at you, you can learn to use your hands,” Hart says. “You can learn to understand hands, eyes, feet, and angles. Now, you can learn to become a better player. It’s when you never learn that shit that you become mush.”

By last fall, Thomas weighed 270 pounds and had transformed into one of the most refined defensive linemen in college football. In Stanford’s annual clash against Notre Dame, he piled up 12 tackles and loomed as a menacing presence in the Cardinal’s 17–10 win. Mike Sanford, who recruited Thomas during his stint at Stanford and became the Fighting Irish’s offensive coordinator in 2015, says that his game plan revolved around slowing no. 90. For one week, part of him wished the Cardinal had recruited a little worse during his final season in Northern California. “He was a force that you couldn’t stop, period,” Sanford says. “I was cursing the very day I engaged in the process. I wish I would have told [him and Christian McCaffrey] that Palo Alto is really a bad place to live.”

When playing against the run, Thomas has violent hands. The flash he exhibits after standing up an offensive lineman allows him to make plays along the line while holding strong at the point of attack. In that way, he resembles the force Bennett can be on early downs. What separates the two is Thomas’s relative lack of experience coming off the edge. Earlier this year, Thomas trained with coach George Dyer at a performance center in San Diego. After working with Thomas for a few days, Dyer called Hart with an observation: He couldn’t get Thomas to turn the corner as a pass rusher. “I said, ‘George, he’s never turned the corner and pass rushed,’” Hart says.

In Stanford’s scheme, Thomas was usually responsible for manning the gap inside the offensive tackle. Compared with a typical defensive end tearing off the edge, he was asked to complete a drastically different, unnatural movement. For some teams, his lack of experience as an edge rusher could be seen as a negative, but in Hart’s eyes Thomas “never having alignment as his friend” is proof that a move to the outside will only make him more dangerous. Thomas agrees.

“Solomon Thomas is a tweener, for me, is a great thing, and it’s going to be a plus for any team drafting me,” Thomas says.

As much as Phillips took from all of his late-night conversations with Thomas, he says what he’ll miss most with his friend leaving for the NFL is their car ride sing-alongs. Their disparate Star Wars opinions didn’t extend to music. The pair was in sync with whatever Drake song blared out of the speakers in Thomas’s white Audi sedan. That was the car with the auxiliary cord. “[Those rides] would leave me sweating, out of breath, and with no vocal cords the next day,” Phillips says. “That’s something that I’ll definitely miss. If I tried that with another one of my friends, they might ask to just [get an] Uber.”

Thomas has long been a Beyoncé fanatic, and he quickly helped Phillips become one, too. In describing his curriculum for Intro to Beyoncé 101, Thomas notes how the order of his playlist is thoughtfully considered. “So, I’m straight off with traditional ‘Halo,’” Thomas says. “I’m starting off slow, getting them into the flow. Listen to her voice. Listen to her music. ‘This is beautiful.’” From there, he ups the tempo, from “Crazy in Love” right into “Partition,” where “she switches the beat up and kills it in two different fashions,” Thomas says. A mix of old and new tracks comes next: “All Night,” “If I Were a Boy,” and, finally, way back to 2003’s “Me, Myself and I.”

“It’s a song you can snap your fingers to, sing along to,” Thomas says. “It’s like, ‘OK! Beyoncé’s got me feeling important.’” Beyond her unassailable talent, Thomas says that his fascination with Beyoncé surrounds what she has come to represent for so many people. “She’s so respected worldwide,” Thomas says. “She’s like the actual queen. Each album, all the way throughout, it has a different message. It has a different reason. She’s trying to get something across.”

He cites 2013’s Beyoncé and its ideas about women’s sexuality as being especially powerful. “I thought album was so amazing because women can talk about those sexual feelings as much as guys can,” Thomas says. “She’s not just putting out songs. She’s putting out feelings and messages.”

On January 21, Thomas put out a rare Twitter message of his own. “So inspired by the #WomensMarch,” he wrote. “I love ALL of our women and ALL of our people worldwide. The unity and solidarity displayed is truly moving.” He’d spent that day thinking about his older sister, Ella, who he describes as his best friend, and his mother, Martha, who he says taught him “everything he needs to know in life.” It was just another instance of Thomas figuring out how to use his standing to make a statement. “You want to stand for something while you have the stage,” he says. Come next week’s draft, the stage is about to get a whole lot bigger.