In 1970, the Elgin Theater in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood decided to screen a strange movie at a strange time. The movie was El Topo, a violent, surrealist Western by Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky that had previously been exhibited only in museums. The time was midnight. Despite its low odds of success, El Topo found an unlikely but unwavering audience at the Elgin. The theater began selling out its 600-seat venue every night and played the film for more than a year. The Midnight Movie, and the modern interpretation of a “cult following,” was born.

Cult films had existed before El Topo, but the Midnight Movie presented a new opportunity for like-minded fans to gather, discuss theories about a film, and publicly demonstrate their fandom. “Whereas you had the multiplex for mainstream, you classically had the midnight movie circuit for cult,” says Xavier Mendik, professor of cult cinema studies at Birmingham City University. “So the Rocky Horrors, the Pink Flamingos, the Texas Chainsaw Massacres, all of those cult classics wouldn’t have been cult without that alternative exhibition forum.”

Today, the gathering place for cult followers has moved from the midnight circuit to message boards, blogs, and social networks. And the types of media worthy of intense fixation have expanded dramatically. On the internet, you can obsess over anything — especially if it’s weird, unsettling, or tragic.

Video games, in particular, have become fertile ground for cult followings, and there is perhaps no game that fits the criteria for cult better than 2000’s The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Rather than having franchise hero Link save Princess Zelda and the land of Hyrule again, the Nintendo 64 title traps him in a bizarro universe known as Termina and gives him three days to stop the moon from crashing into the world and killing everyone. As a highly unconventional follow-up to what is often hailed as the best game of all time, Majora’s Mask was always doomed to be something of a black sheep in the Zelda franchise. But its peculiar mix of mystery, horror, and apocalyptic dread — all spun through the eyes of a 10-year-old kid and his child adversary — helped it hit a note that few video games even today are able to: It felt strikingly human.

In the real world, Majora’s Mask was met with a question mark, then quickly put aside as gamers moved on to the newly launched PlayStation 2. But online, it’s evolved into something more than a game. On Zelda fan sites, gamers plumb the game’s every pixel for symbolism about death or the nature of morality. On YouTube, the game’s most subtly bizarre elements have been reinterpreted in more explicit ways to create creepypastas, a narrative genre that originated in message boards and email chains in the late 2000s and now serves as the ghost stories of the internet. And in quiet corners of the web, on blogs and Tumblr pages and DeviantArt accounts, people are using art inspired by this game to express their inner turmoil. Majora’s Mask is a strange game that has launched even stranger subcultures and found itself resurfacing, again and again, in unusual and sometimes horrific contexts.

Though Zelda is thought of as a formulaic franchise today, it was still an extremely experimental series at the turn of the century. The second Zelda game was a side-scrolling action RPG. The fourth took place in a dream world inspired by Twin Peaks. The creation of Majora’s Mask — the sixth game in the series — began with its own real-world doomsday clock. Following the success and wide acclaim of Ocarina of Time, the fifth Zelda game and one of the most ambitious titles in video game history, franchise creator Shigeru Miyamoto wanted his team to make a sequel in a single year. He also wanted an inventive new gameplay system to differentiate the sequel. The stress of the tight deadline gave game director Eiji Aonuma nightmares.

Many of the game’s most striking features were shaped by this brutal deadline. Each Zelda game is supposed to be filled with a colorful cast of new characters; to save time, Majora’s Mask reused the character models from Ocarina of Time and gave the characters new identities, adding a surreal, dreamlike flair. Zelda games are supposed to be filled to the brim with dungeons (Ocarina has nine); Majora has a paltry four, and refocuses much of the action in a large hub city known as Clock Town. The world of Termina is smaller, but denser. With no time to create a sense of epic sprawl, the game designers were forced to turn inward.

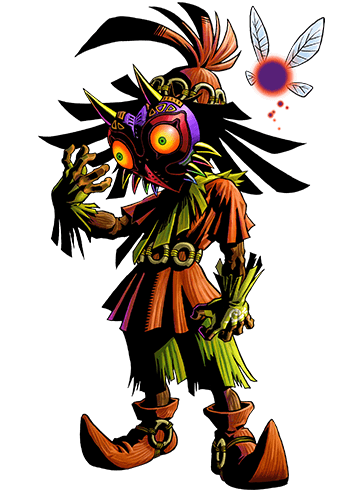

Link has three days to save Termina from Skull Kid, a lonely boy who has used the power of Majora’s Mask to send an angry-faced moon hurtling toward Clock Town. It’s impossible to stop the moon in a single three-day cycle, but Link can play a magic song on his ocarina to reset the game clock and play through the period again and again as he pieces together clues on how to stop Skull Kid. That gives him an endless amount of time to traverse the game’s dungeons, help the people of Clock Town, and slowly learn the precise daily schedules of every denizen of Termina. It’s Zelda meets Groundhog Day.

For its time, the game’s mechanics were startlingly complex, even compared with its immediate predecessor. “It sets a really adversarial stance against the player,” says Bob Mackey, cohost of the retro gaming podcast Retronauts. “It’s not quite Dark Souls, but it’s not a friendly game to play. There’s always a ticking clock. You’re constantly reminded of your timer by the giant, angry face looking down at you from the sky. It’s a very hostile, threatening game to play, and I think that’s why a lot of these creepypastas are spawned from it.”

But there were a lot of unusual things about Majora’s Mask besides its mechanics. Zelda typically treats good and evil as binary concepts, often going so far as to split the world between light and dark realms (Ocarina, for instance, showcases Hyrule as a carefree land when Link is a kid and a barren dystopia when he’s an adult). The games are less legend than fairy tale. In Majora’s Mask, there is only one world; it is careening toward utter ruin, and everyone knows it. Helping the characters make peace with their own impending doom, only to have them forget your existence every time you reset the clock, doesn’t exactly feel heroic. Fans of the game kept coming back to a single word to describe its tone: melancholy.

Majora’s Mask also has an intense fixation on death. Link dons a variety of masks throughout his adventure to morph into other creatures (in an agonizing transformation), but each one is a specific person who died tragically and is still mourned by other characters in the game. As the apocalypse inches closer in the game’s three-day cycle, the characters cope with their own mortality in different ways. The city guards, who typically eye Link as he enters or leaves Clock Town, stand fixated on the moon with their hands over their hearts. A couple that Link can reunite via a side quest have a loving embrace moments before the moon crashes. A once-brave swordsman cowers in his dojo and yells, “I don’t want to die!” And if you want, you can let the three days expire and watch the moon destroy the world as Link is consumed in a fiery heat death. No wonder fans took it upon themselves to make a doomsday clock based on the mythical Mayan calendar that was themed after the game.

All these strange elements have been part of the game since it was released in 2000, but they weren’t immediately acknowledged. The reviews at the time were positive but not as effusive as Ocarina’s were, noting that the game was annoyingly obtuse. (It was too tough for me to beat as a kid.) In North America, it launched on the same week as the PlayStation 2, making it technically obsolete at its debut. It became the worst-selling game in the franchise’s 14-year history, and Nintendo took Ocarina as the blueprint for all future Zeldas, not Majora.

The game’s poor performance on the market set it up well for a second life as a cult object. Cult films are often initially regarded as failures, notes I.Q. Hunter, a professor of film studies at De Montfort University and author of Cult Film as a Guide to Life. “Maybe it was a disaster with critics or didn’t make much money at the box office. It was kind of overlooked. And then, a little bit later, a particular group of people, often a subculture, will pick up on that film and get kind of obsessed about it.”

Despite its relative failure on the market, Majora slowly accrued an intense fandom. People began to connect the dots of Majora’s Mask’s weirdness, and even created some new dots of their own. The game arrived just as home internet was becoming ubiquitous in the United States, and the ingredients for cult fandom were being baked into the narratives of a variety of mainstream creative works — think The Matrix, Metal Gear Solid 2, or Lost. Anything could be weird or secretly complex, even if it was engineered to sell millions. And the internet could provide validation for every off-the-wall theory through venues such as Doc Jensen’s Lost recaps for Entertainment Weekly.

“Not only has the internet accelerated conspiracies, but the way in which cultists relate to films has become quite commercially viable as well,” Hunter says. “A cultist won’t just watch a film once. They watch films lots of times. They want to talk about it a lot. Increasingly, a lot of techniques on TV texts — and I guess this is true of video games as well — have this sort of world-building aspect to them. They often are deliberately quite complicated. They encourage you to watch time and time again and to start to watch like a cultist.”

Cody Davies, webmaster of the Zelda fan site Zelda Universe, says that fan theories about the game’s meaning began to gain traction around 2006 or 2007. “Once people were looking at it again not in the context of a new release, just going back and playing it, I think that’s when it started to shift,” he says.

Today fan and conspiracy theories crowd Zelda fan sites and YouTube. Take your pick of exotic arguments: Link is dead throughout the game; the fourth dungeon is an allegory for the Tower of Babel; the five main regions of Termina represent the five stages of grief; both the game’s heroes and villains are fundamentally amoral; the game is a meta-commentary about its own arduous creation under a one-year deadline.

“That’s pure cult activity,” Mendik says of the intense philosophizing. “It’s all about the idea of people reading non-mainstream interpretations into materials. People are reading these kinds of conspiracy theories into a kids’ game.”

That’s actually the strangest thing of all about Majora’s Mask — it’s ostensibly for and about children. Nintendo is a family-friendly developer, and Zelda is a franchise for all ages. Majora’s Mask, while being rated E for Everyone, is probably the closest the company’s first-party studios have flirted with the horror genre. “What speaks to me about horror is that it feels very, very emotionally honest to acknowledge we’re all afraid of dying, we’re all afraid of decay, we’re all afraid of our bodies not being here anymore,” says Danielle Riendeau, the managing editor of the Vice gaming website Waypoint. “Here’s a game that says, ‘The world’s going to end. You can watch it happen in real time.’ I think it’s really speaking to the same emotion.”

The horror in Majora’s Mask, the game, is implicit. But over the last few years fans have taken those unsettling elements in a much more explicit direction.

One of the most famous scenes of Majora’s Mask technically isn’t even in the game — at least, not the version Nintendo released. After being trapped in a dark cave by Skull Kid, Link plays a song on his ocarina. A scream erupts for a split second as the screen cuts to black. A dialogue box pops up: “You shouldn’t have done that …”

Link is suddenly transported to another underground cavern. He checks a stone that’s supposed to reveal the time. “You shouldn’t have done that …” He opens a treasure chest. “You shouldn’t have done that …” He’s teleported aboveground, where he encounters an owl whose head has been twisted upside down. “You shouldn’t have done that …” The game freezes abruptly, then cuts to black again after the same millisecond scream. Up pops a new dialogue box: “BEN is getting lonely …”

The scene is from “Ben Drowned,” one of the most famous creepypastas, about a college student who buys a haunted copy of Majora’s Mask at a yard sale. The player is pursued relentlessly in a glitched-out version of the game by a dead boy named Ben, represented by a creepy in-game statue of Link.

The story was crafted by Alex Hall, himself a college student at Saint Louis University at the time. Hall had been a big fan of Majora’s Mask since its debut, and even as a kid recognized the game was a stark departure from Ocarina of Time. “This mysterious, ominous atmosphere of Majora’s Mask was a perfect setting for a haunted creepypasta to take place in,” he says.

Hall posted a thread on the paranormal board of 4chan, /x/, in September 2010 under the username Jadusable. “Okay, /x/, I need your help with this,” he began. “This is not copypasta, this is a long read, but I feel like my safety or well-being could very well depend on this. This is video game related, specifically Majora’s Mask, and this is the creepiest shit that has ever happened to me in my entire life.”

He then launched into a long story about a faulty version of Majora’s Mask that appeared to be possessed by a ghost. He wrote in painstaking detail about each bizarre scenario Link found himself in, wandering through an abandoned Clock Town, spontaneously bursting into flames and lying unconscious (or dead) as Skull Kid looked on in silence. Then, as proof, he posted a video on YouTube that supported his outlandish claims. The thread received hundreds of comments, the video garnered 100,000 views in less than two days, and gaming blogs like Kotaku picked up on the story.

Hall had used an emulator called Project 64 which allowed him to rearrange and warp the Majora’s Mask assets as he wanted. The plot of the video is abstract — there’s no particular reason or coherence to the game malfunctioning in this way. But the more familiar you are with Majora’s Mask’s tightly constructed world, the creepier it is to see Termina collapsing in on itself. “There’s something spooky about something that people have programmed to do a specific thing that has suddenly gone haywire and is starting to turn malicious,” Hall says.

He followed up his initial post with more written dispatches and videos, created in real time based on the suggestions from 4chan users about how to rid the game of its curse. Eventually it’s revealed that “Ben,” a sort of ghost turned digital virus, hijacked Jadusable’s computer and provided a false account of the story’s resolution. A secret note from Jadusable offers the “true” telling of events and references videos that were never published, seemingly because Ben had deleted them. Like Majora’s Mask itself, the plot of the creepypasta is ambiguous, lacking in moral clarity, and centering on death.

Hall says he thinks that some people were drawn into believing the horror story was real, though most suspended their disbelief simply to maximize its entertainment value (he revealed it was fiction after a few weeks). Either way, it helped augment the popular perception of the game. “Ben Drowned” has drawn comparisons to “Slender Man,” a notorious creepypasta that authorities say a pair of 12-year-old Wisconsin girls used as inspiration to stab a classmate 19 times in 2014 (the case has yet to go to trial). Horror writer Clive Barker was at one point planning to do live-action short films about both horror stories. “Because of ‘Ben Drowned,’ I think people look at Majora’s Mask in a different way now, a little more horror-themed than before,” Hall says.

Even after “Ben Drowned” was revealed as fiction, “Ben” lived on. Fans of the creepypasta insisted that he was real. (So real that when Hall made a parody video of “Ben Drowned” for April Fools’ Day in 2012, he received death threats.) They drew fan art and crafted new narratives about the boy who drowned. Eventually Ben’s avatar shifted from being the creepy statue in Majora’s Mask to a new fan-made rendering of Link with blood dripping from his eyes. This was not Nintendo’s intent, or even Hall’s — Majora’s Mask had taken on a life of its own online.

“If you think about what a cult fan does, regardless of whether it’s a cult video game or a cult film fan, they dissect, define, pull apart the narrative as a whole,” says Mendik. “So they’re looking for discrete elements. It’s key elements of excess they fixate on.”

Despite its ambiguity, Majora’s Mask is still grounded in a physical cartridge and a definitive, copyrighted work by a major corporation. “Ben Drowned” has over time drifted further and further from its ties to the Zelda franchise — on fanfiction.net, “Ben Drowned” is listed as a separate category from Zelda. And though it began as Hall’s personal work, there are now so many “Ben Drowned” videos, stories, and images that it’s easy to forget how the horror story started. Mendik points out that cult objects are often open to an “endless multiplicity of audience interpretation.” “Ben Drowned” appears to fit that criterion, just like the work that inspired it. As Hall was wrapping up the original creepypasta story arc, he changed the location of the YouTube account uploading the videos (and seemingly possessed by Ben) to “Now I am everywhere.”

For all its strange turns, the “Ben Drowned” story is mostly harmless internet fun, the digital version of telling tales around the campfire. That’s where I assumed this story would end. But this past year, the universe of “Ben Drowned” (and, by association, Majora’s Mask) intersected with real-life tragedy.

On December 30, 2016, a 12-year-old girl named Katelyn Davis used the app Live.me to broadcast her own suicide outside her home in Cedartown, Georgia. The video was recorded and quickly spread to other video sites such as Facebook and YouTube. “We did our due diligence to try to remove it, but it’s impossible,” police Chief Kenny Dodd told Fox 5 in Atlanta. “There’s too many websites that have it. There’s too many people that have it on their device.” Major social platforms have now deleted the video, but it’s still discoverable in the bowels of the internet.

After her death, internet users began trawling through Katelyn’s online presence for clues about why she took her life, reposting her vlogs on YouTube. A blog on the website Quotev that has been attributed to Katelyn was discovered. In the blog, she writes about feelings of depression and loneliness, as well as her troubled home life. She also accuses a family member of sexual abuse, a claim she also made in her suicide video. According to KTLA 5, police in Polk County acknowledged the existence of the blog and said they were investigating the allegations. The Polk County Police Department also issued a warrant for Katelyn’s phone, Facebook account, and a third social media site, according to the Polk County Standard Journal. (The Polk County Police Department did not respond to my multiple messages and phone calls requesting an update of the investigation and confirmation of the veracity of Katelyn’s blog post.)

The blog attributed to Katelyn largely focuses on her inner struggles and challenges with her family, except for one post that focuses on a person she calls “Ben Drowned.” She wrote that he is the “real” Ben Drowned but that she hasn’t talked to him in months. From the blog post alone, it’s unclear whether Katelyn is talking about the fictionalized character that has spread across the web or an actual person who assumed the alias “Ben Drowned.” The videos that appear to feature Katelyn before her death seem to suggest that “Ben” is a person who catfished her in a false online relationship.

“I can’t live without him,” the post reads. It’s accompanied by a piece of fan art of the “Ben Drowned” character from the Majora’s Mask creepypasta, featuring a Link with blood-red eyes beckoning a violet fairy. The page header features a photo of a girl who appears to be Katelyn next to another dark drawing of Link. The post also references “Slender Man.”

“We’re really in this new era when it comes to issues around mental health and social media, and we’re just starting to understand it,” says Ben Michaelis, a clinical psychologist who serves as an adviser for Crisis Text Line. “People are sort of looking to connect with other people, but unfortunately, in these sorts of cases, you have very tragic results because she was reaching out to the world and not getting the help that she really needed.”

Katelyn’s death left Hall reconsidering his creation and pondering issues of authorial responsibility.

“That was the difficult part with Katelyn,” says Hall. “I wondered if I never wrote that story, would that stuff have still happened? Or those girls who [tried to] kill someone with Slender Man a few years back. If that didn’t exist, would that have ever happened? No one can ever say for sure. It’s a hard moral issue and a tragedy, but I don’t think that authors can necessarily be held responsible for what some fans do because of an obvious work of fiction. There are both sides to this coin — there are plenty of people who have personally thanked me for writing the story, saying that it had helped them get through a really dark time in their life. I suppose it’s one of the burdens of publicly publishing your work to a wide audience; you have to take the good with the bad.”

Katelyn’s death has created a large number of followers who are awaiting new details in the case. Katelyn Nicole Davis RIP Angel has more than 6,300 followers on Facebook. #JusticeForKatelyn has more than 1,000 members. At least half a dozen similar Facebook groups exist with hundreds of members each. They piece together clues online about the circumstances that led to Katelyn’s death, including the mysterious Ben Drowned persona. When the Polk County Police Department posts about any topic on Facebook, commenters swarm with questions about Katelyn’s death. The people who have devoted themselves to understanding Katelyn’s death have also spent time celebrating her life through photos and drawings. “Fan art of Katelyn!!” reads one post, showcasing a photo of the girl alongside a colored-pencil illustration. “It’s amazing how many of you have reached out and sent condolences and made memes and this art is beyond words. It restores my faith in humanity!!”

This is a new online community, with a new obsession, formed through tragic circumstance. “[The internet] has a lot of possibilities for positive impacts,” Michaelis says. “There’s also possibilities for negative things, like obviously what happened to this young woman. We just need to be responsible with this brand-new power that we have.”

In crisis? You can text the Crisis Text Line at 741741 for free, 24/7 confidential support.