Anthony Davis is about to become only the 22nd player to average at least 27 points and 10 rebounds in a season. The Brow’s 27.7 points and 11.8 rebounds per game will go down as one of the NBA’s most remarkable great-stats-on-a-bad-team seasons. Davis will become only the 12th player in league history to post 27 and 10 on a team with a record below .500, according to data provided by NBA.com to The Ringer.

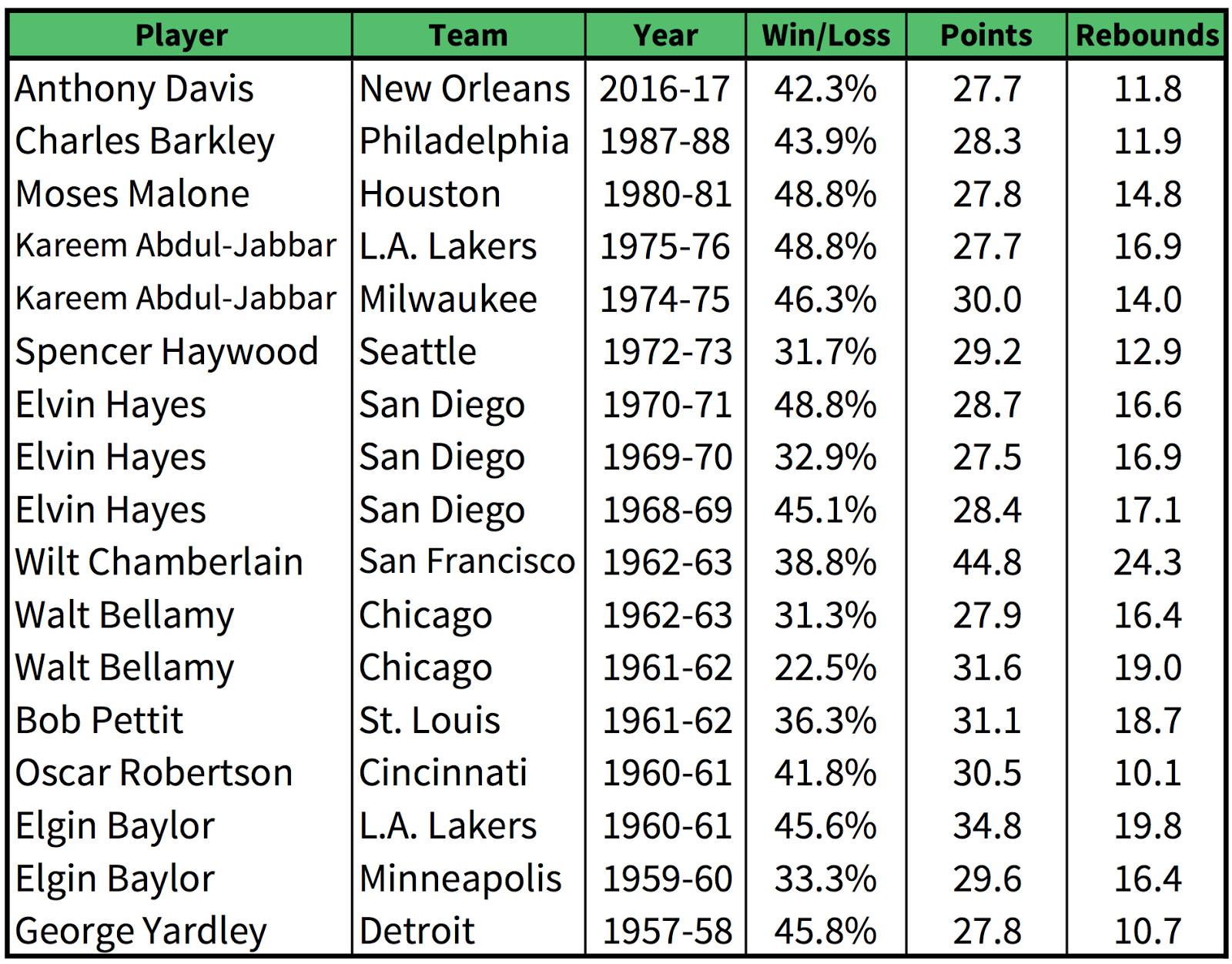

The last time a season like this occurred was nearly 30 years ago, when Charles Barkley averaged 28.3 points and 11.9 rebounds for the 36-win Sixers in 1987–88. Most of the other instances come from the 1960s. Here’s the list:

This is a list dotted with Hall of Famers, which Davis will be someday if he stays healthy. There aren’t many big men capable of dominating on both ends of the floor like he can. And at only 24, he hasn’t reached his prime. Davis is a beacon of hope. But here’s a warning for Pelicans fans: That’s the last bit of good news I have for you.

Eight of the 11 players listed above left their teams within four years of posting a 27–10 in a losing campaign. Even the greats aren’t exempt from being moved. Philly traded Barkley to Phoenix in 1992, Kareem was traded in the summer of 1975 to the Lakers, and Wilt was sent to Philly during the 1965 All-Star break.

Davis? We’ll find out. The Pelicans All-NBA center can hit free agency as soon as 2020 (he has a player option for 2021, which he will likely decline). The new decade might seem like ages away, but it’s coming fast in NBA time. You may look at that list and think that it’s ancient history. But players have more freedom of movement now than they did back then. Why else would Oscar Robertson stay in Cincinnati? The implementation of modern free agency in 1988 changed everything.

This century, five players other than Davis have averaged at least 27 points on teams that finished below .500: Jerry Stackhouse (Pistons, 2000–01), Tracy McGrady (Magic, 2003–04), Kobe Bryant (Lakers, 2004–05), Allen Iverson (Sixers, 2005–06), and Carmelo Anthony (Knicks, 2013–14). Stackhouse was dealt in 2002. McGrady was traded in 2004. Iverson was traded in 2006. Only Kobe and Melo stuck around. It worked out for Kobe. Melo looks to be on the way out this summer.

Why does this happen? Because sometimes a franchise cornerstone is a team’s only viable trade asset. When you’ve gone as far as you can as a one-man band, it’s usually time to get a different band together.

The Pelicans want to keep this band together, and made an all-in move to acquire DeMarcus Cousins. The team is zigging with a twin-towers lineup while everyone else is zagging and going small ball. So far the Pelicans’ plan hasn’t worked. Though they’ve won four of their past five games, three of the wins have come against non-playoff teams, and they’re 5–7 in games Cousins has played. There’s been a lot of this:

Cousins is a talented, ball-dominant player, but his biggest talent diminishes Davis’s value. The Brow’s worst offensive skill is his 3-point shooting, yet when Cousins bulldozes defenders, all Davis can do is float around the arc. Per NBA.com, Davis’s effective field goal percentage is 16.3 percent higher when Cousins is off the floor. The Pelicans outscore teams by 9.2 more points per 100 possessions when Davis is on the floor without Cousins than they do when Cousins is on.

Most blockbuster trades happen during the summer, so New Orleans’s struggles could be chalked up to a lack of familiarity. It’s hard to integrate new players midseason, especially high-usage superstars like Cousins. The poor numbers will likely normalize as the sample size grows, but the pairing is not off to a good start. And if the slide continues into next season, then the question becomes whether there is anything the Pelicans can do to build a winning roster around Davis by the time he hits free agency in 2020.

The Pelicans might’ve acquired Cousins for a bargain, but they still lack much flexibility. Missing the playoffs and winning the lottery, so they could keep their top-3-protected first, is their best hope at adding more talent. If point guard Jrue Holiday is re-signed this summer, they’ll be out of cap space unless they move the contracts of Omer Asik and Alexis Ajinca (or even Solomon Hill). To make those moves, they’d need to toss in future draft picks since they likely don’t have any players on the roster that would entice a team to absorb Asik or Ajinca. Even creating cap space doesn’t guarantee adding an impact player in this year’s incredibly thin free-agent class. Never mind the elephant in the room: Prior to the trade, Cousins’s agent, Jarinn Akana, said it’s “highly unlikely” his client would sign an extension with the Pelicans this summer. If Cousins walks when he becomes a free agent in 2018, it would leave the Pelicans right back where they started, or possibly in a worse spot.

The promise of the Brow-and-Boogie marriage is exciting for the league because it’s rare to see a transcendent superstar, having one of the greatest individual seasons of the century, join forces with one of the league’s great big men. And it’s no fun for fans watching guys toil away in mediocrity. A player’s legacy grows when he goes deep into the playoffs rather than seeing his season end in April. But right now the Pelicans are a team with zero title hopes, clinging to 8-seed dreams. Over league history, stars stuck in those spots don’t stick around too often. Maybe things will be different with Davis, but it won’t be unless the Pelicans make drastic changes before time’s up.