There has never been a better time in NBA history to be a point guard. Instead of walking the ball up the floor, throwing it inside, and waiting for a kickout, the best PGs these days push the pace, hold the ball for most of the game, and initiate the majority of their team’s offense. The pace-and-space era began in earnest back in 2004, when the Suns started playing 3-point shooters at power forward and spreading the floor for Steve Nash. More than a decade later, centers are shooting 3s and defenses are being stretched past their breaking points. If guards in the ’90s were maneuvering through cramped streets to get to the rim, guards in the 2010s are roaring down wide-open interstates.

Running point has become so much fun that everyone wants to do it. The Rockets moved James Harden to the position in the offseason, and while many assumed it was merely a matter of semantics, the change has made him the front-runner for MVP. Give a player who can dribble, pass, and shoot the freedom to push the ball in transition and play in maximum space in the half court, and there’s no telling what he can do. No statistical accomplishment is safe.

Eight point guards were selected to this year’s All-Star Game, and that’s without counting Giannis Antetokounmpo, a do-everything monster who leads the Bucks in points, rebounds, assists, steals, and blocks. Chris Paul would have made the cut if he were healthy, and the depth at the position means Mike Conley, Eric Bledsoe, Damian Lillard, and Goran Dragic are on the outside looking in. It’s hard to win in this league without a high-level point guard, and many of the worst teams will be looking for help at the position in this year’s draft.

Ranking point guards is an exercise in futility, since their performance is so dependent on the players around them. Steph Curry is the same player he was when he won two consecutive MVPs, but his stats have gone down now that he’s playing with Kevin Durant. Conversely, Russell Westbrook is averaging a triple-double with Durant gone. In college basketball, less-talented players depend on their point guard to make them better, but at the highest level, a point guard can be only as good as the players around him allow him to be.

So instead of a straight ranking, I decided to break down how the eight point guards in this year’s All-Star Game, plus Paul, compare at various aspects of the game.

Stats current as of Wednesday afternoon.

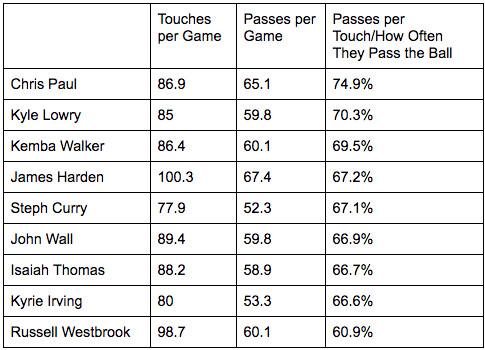

Who plays the most like a traditional point?

The days of the point guard as a pure facilitator have come and gone. A point who can’t threaten a defense as a scorer is playing with one hand tied behind his back. Nevertheless, the guy who brings the ball up the floor still has to keep everyone else involved in the offense. Finding a balance between looking to pass and score is tricky, and it depends in large part on the talent of the other four players on the floor. So how much variation is there at the position? Thanks to the high-definition tracking cameras in every NBA arena, we know exactly how many times a game each point guard touches the ball, and how many times they pass it.

The likelihood of Paul passing the ball on a given possession is nearly 15 percentage points higher than that of Westbrook, who is using possessions at a historic rate. Compared with last season, Russ is getting 10 more touches a game, but he’s making only two additional passes. Paul is a precision weapon who carefully picks and chooses his spots; Westbrook is a blunt-force instrument who presses the issue at every opportunity. While Paul’s style of play boosts his advanced statistics, that doesn’t necessarily make it more effective. He’s a career 47.3 percent shooter, a great number for a point guard, but would he be better off sacrificing efficiency to boost his scoring? Look at the Clippers-Thunder playoff series in 2014. Paul averaged 22.5 points on 51 percent shooting, and Westbrook averaged 27.8 points on 49 percent shooting. The differential in the six-game series was a mere five points; those extra five points a game were pretty valuable.

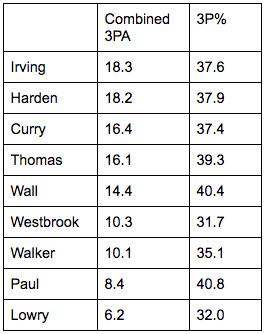

Who plays in the most space?

Playing point guard in the NBA is like playing a video game. The more shooting on your team, the easier the difficulty level. If the opposing defense has to guard four players spread out 25-plus feet from the basket, getting to the rim is easy. If it can pack the paint and dare the other four players to shoot, it becomes almost impossible. So who is playing on easy, and who is playing on hard? To make this calculation as simple as possible, I looked at the other four players in each point guard’s most commonly used lineup and logged the number of 3s they take and make per game.

Harden, Curry, Irving, and Thomas all play in canyons of space, and, perhaps not coincidentally, the Rockets, Cavs, Warriors, and Celtics have four of the top six records in the NBA. On the other end of the spectrum, Westbrook and Kyle Lowry, in particular, are navigating through minefields. Most of the Raptors’ best 3-point shooters come off the bench, so Lowry is spending huge chunks of the game with only DeMarre Carroll to spread the floor for him. The Thunder have hardly made any effort to pair Westbrook with shooters at all, figuring he can bully his way to the basket regardless. It makes you wonder what stats he would put up if he traded places with Harden.

Of the nine teams on this list, only one — the Celtics with Al Horford — gets much 3-point shooting from its starting center, although the Warriors (with Draymond Green at the 5) and the Cavs (Channing Frye) regularly play five-out basketball. The pace-and-space era may not yet have reached its peak, since there’s still plenty of room to stretch defenses out farther and pair the league’s elite point guards with stretch 5s.

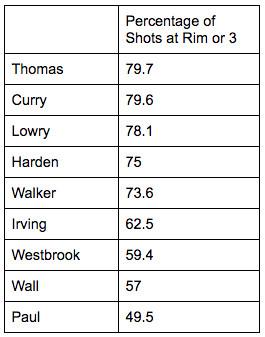

Who is the most Moreyball point guard?

Under GM Daryl Morey, the Rockets have built an offense around maximizing the two most efficient shots in basketball — 3s and shots at the rim. Moreyball is slowly taking over the rest of the league, thanks in large part to the advent of the spread pick-and-roll, which emphasizes production in those areas. The midrange specialist has become the textile worker in the Industrial Revolution; their livelihood ripped out from underneath them, the “long 2” a curse word. So which elite point guard has a shot distribution that most closely fits the ideal?

Surprisingly enough, Harden, whose game seems as if it were constructed in the lab by Morey, isn’t the most Moreyball point guard. That honor goes to Thomas, who beats out Curry and Lowry by the narrowest of margins. All three take approximately four of every five shots from the two sweet spots on the floor. But while Curry and Lowry take more than half their shots from beyond the arc, Thomas is an equal-opportunity shooter who takes almost as many shots at the rim (7.6) as he does from 3 (8.3). Despite being the smallest player in the group, he trails only the über-athletic Westbrook in terms of how often he gets into the paint.

Who runs the pick-and-roll the best?

The pick-and-roll is the foundation of most offenses in today’s game, and the vast majority of sets are initiated by a ball screen at the top of the key. Every good point guard is good in the two-man game, but which one is the best? We have to go beyond statistics to answer this question. We can look at how many pick-and-roll possessions guards run and how efficient they are when doing so, but those numbers are determined by the structure of their offense, the skill sets of their partners in the two-man game, and the amount of space they are playing in. It’s a lot easier to throw lobs to Andre Drummond or DeAndre Jordan than Zaza Pachulia.

There are three separate components to running the pick-and-roll effectively. The first is the ability to shoot off the dribble. The easiest way to defend the pick-and-roll is to go under the screen and dare the ball handler to shoot. If you can’t force the defender to respect your shot, the play can be stymied before it gets going. Conversely, the more effective a shooter the ball handler is, the more opposing defenses have to extend out to prevent him from getting a clean look, which opens up opportunities for plays behind them.

The second is the ability to attack a switch. Rather than dealing with the intricacies of all five defenders moving on a string and communicating as one, more teams are just switching the screen. The Cavs used this strategy in last season’s NBA Finals, taking advantage of Curry’s limited mobility following his postseason knee injury to switch either Tristan Thompson or LeBron James on him. They dared him to beat them off the dribble, effectively neutralizing the Warriors offense.

Only a guard who can shoot well and actively looks to score can fully unlock the potential of the pick-and-roll. If the defense doesn’t go under or switch, the ball handler can take advantage of the space created by the screen to get into the paint and either throw the lob to the rolling big man, find a shooter spotting up off the ball, or score himself. That’s when the traditional qualities of a point guard, the ability to manipulate the defense, make passes in tight spaces, and anticipate where everyone will be, come into play.

So who is the ideal guard to run the pick-and-roll? There’s no right answer to this question, but there are wrong ones. It’s probably not Wall or Westbrook, the two worst 3-point shooters of the bunch. You don’t want someone who turns the ball over too often, which is a problem for Harden, the only remaining guard on the list with an assist-to-turnover ratio of less than 2-to-1. You want an elite one-on-one scorer who can consistently punish a switch, which eliminates Walker, who’s only scoring 0.65 points per possession in isolation plays this season.

That leaves Paul, Irving, Thomas, Lowry, and Curry, all of whom represent an almost impossible challenge coming off a screen. You can’t go under on any of them, you don’t want to leave a big man on an island against them, and they can all get into the lane and drive and kick. Even though he struggled in the Finals against switches, I would still take Curry, because he’s the best shooter of the six and he’s the tallest, so it’s easier for him to get a shot off. The irony is that he has fewer possessions in the pick-and-roll than any other guard on this list.

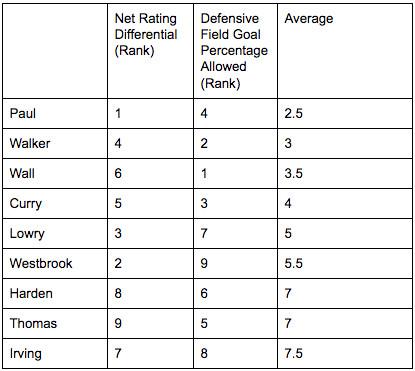

Who plays the best defense?

Measuring defense is incredibly tricky, especially at point guard, where so much of a player’s responsibility comes within a team concept. There’s also a ton of cross-switching at the position, as the best point guards are hidden on less-talented players in order to preserve their energy. So while it’s important to look at how a player performs defensively in one-on-one situations, the caliber of players he is guarding will vary depending on how he is used. Thomas, who shares the backcourt with an elite perimeter defender in Avery Bradley, doesn’t have nearly as many tough individual assignments as Lowry or Paul, who play with DeMar DeRozan and J.J. Redick, respectively.

In order to balance how a player defends individually with his impact on his team’s defensive performance, I looked at their field goal percentages allowed when they are the primary defender as well as the difference in their team’s defensive rating when they are on the floor and when they are off. From there, I ranked how all nine point guards compared with each other, and then took the average of both numbers. This doesn’t give a completely accurate picture of their defensive performance, since the difference between Thomas (ninth) and Harden (eighth) in net rating is the same as the difference between Harden and Lowry (third). Still, it is an interesting snapshot:

The numbers pass the smell test, since Paul is a perennial all-defensive team selection and Kyrie is a notorious slouch defensively. In terms of reputation, the most surprising placement on this list is probably Walker, who doesn’t have nearly the physical profile of someone like Wall. Walker has benefited from playing under Steve Clifford, one of the best defensive minds in the business, and he has become adept at using his quickness to get into the dribble of bigger players. He’s third in the league in charges drawn this season.

Who makes his teammates better?

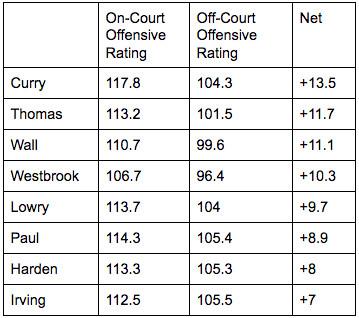

On-court vs. off-court numbers never tell the whole story, since you don’t want to penalize a player for having a good backup or reward him for having a bad one. However, they can be revealing, and, as you would expect, all of the league’s top point guards significantly improve their team’s offense when they are in the game:

To see the power of context in these numbers, all you have to do is look at Kyrie. LeBron James essentially serves as the Cavs’ backup point guard, running the offense when Kyrie isn’t. As you might have heard, James thinks the Cavs need another playmaker. It’s going to be hard for Kyrie to have anywhere near as big an impact on the Cavs as Thomas does with Boston, since the Celtics’ backup point guard is Terry Rozier and they don’t have a legitimate second option they can run offense through when Thomas isn’t in.

However, while it makes sense for Kyrie to be at the bottom, it’s strange to see Steph at the top. The Warriors usually have Durant in when Steph is out, yet they still have a huge gap in offensive efficiency without their star point guard. The Warriors lose more when Steph is out than the Celtics do with Thomas out, even though this offseason Durant chose to play in Golden State and not Boston. That’s the difference between having a point guard who is a career 36.6 percent shooter from 3 and one who is a career 44.1 percent shooter. There are many different ways to be a great point guard, but one path is smoother than all of the others.