Lane Kiffin Has Something to Say

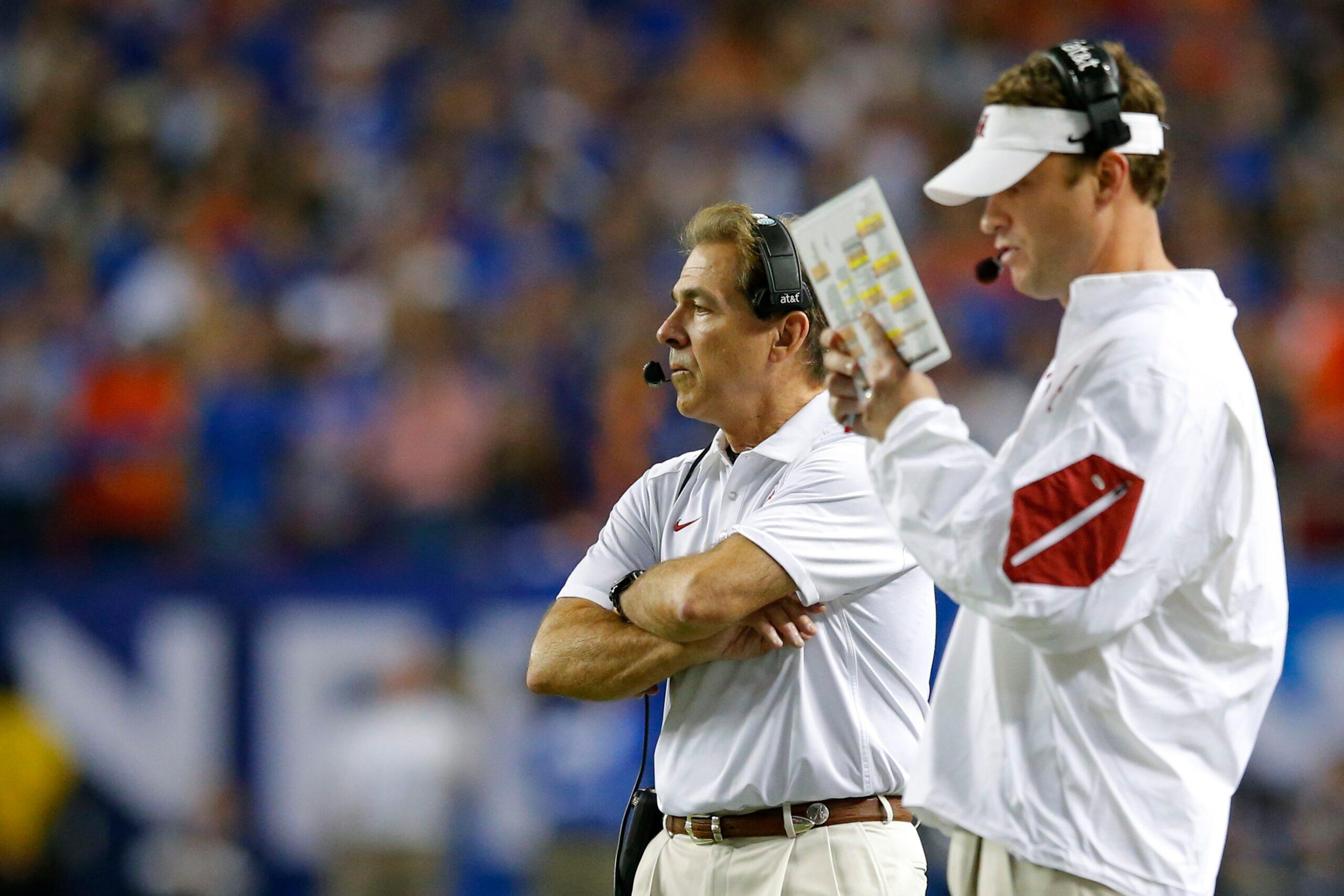

Long known as college football’s swaggering and job-hopping lightning rod, Kiffin has sparked one of the biggest turnarounds in the country at FAU, and in so doing, has sparked a change in his own career. Naturally, he’d like to talk about it.Lane Kiffin has some thoughts he’d like to share. You probably know this. You may know it because you’ve seen the Florida Atlantic coach’s Twitter account, where he tweaks his former boss Nick Saban and trolls his former team Tennessee. Or you may know it because you’ve recently witnessed him talking to reporters, on the radio and on TV, giving the national media a peek inside the program he’s building down in Boca Raton. Or perhaps you know it intuitively, because no matter how far he may have receded from college football’s biggest stage, you never lost the sense that at any given moment, somewhere, Lane Kiffin is probably talking shit.

Right now, he’s leaning forward in the chair at his desk in his office in South Florida. His voice is quiet, his words meandering. He jabs a plastic fork at a Styrofoam container full of takeout noodles, and he unleashes a few things that have been on his mind.

On the mattresses burned at Tennessee after he bolted for Southern Cal: “To me, that’s a good thing.”

On the airport tarmac where USC left him after firing him immediately after flying home from a loss: “That wasn’t because I was disliked.”

On his Twitter trolling, which includes photos of Alabama’s Saban in ripped jeans and of North Korea’s Kim Jong Un in a Tennessee coaching jacket: “If you think about it, it’s completely backward. I’m actually doing the right thing.”

Most successful people do it differently than I did. I did it backwards. I was making my learning mistakes on the national stage instead of the other way around.Lane Kiffin

He grins. He’s just finished his first season at FAU, where he’s already won 10 games, one more than in the program’s last three seasons combined, capped by a Conference USA championship and an appearance in Tuesday’s Boca Raton Bowl against Akron. For years, he has been known largely as college football’s swaggering and job-hopping lightning rod, a man who seemed to stumble into high-profile job after higher-profile job, incinerating bridges on his way. Now that he’s a year removed from a successful-if-tumultuous stint as offensive coordinator under Saban and fresh off of leading the Owls to one of the biggest turnaround seasons for any program in the country, more and more people are confronting a sometimes-confounding truth: Despite his history of fallout and questionable judgment, Lane Kiffin is a good football coach. Throughout his career, he has left jobs in bizarre fashion. Even at FAU, he has made highly criticized decisions, like his choice to hire former Baylor assistant Kendal Briles, who was later mentioned in a lawsuit as someone who played a role in a culture that condoned sexual violence in Waco.

For now, though, many fans and media members have focused far more on Kiffin’s moment of social media schadenfreude and on-field success. He’s done perhaps the best job of his career at a school that hadn’t posted a winning season since 2008, increasing attendance by about 108 percent and generating a buzz that the quiet commuter campus has rarely enjoyed. “I’m having fun,” he says. “This job is supposed to be fun.”

That means winning, mostly, but for Kiffin, it also means upending norms around coaching decorum. It means making jokes at Tennessee’s expense when multiple coaches turned down the Vols’ advances after a fan revolt led them to rescind an offer to Greg Schiano and suggesting that Alabama lost last season’s title game and this year’s Iron Bowl because Kiffin was no longer calling the Tide’s plays. It means extending invitations to “#thefaU” to everyone from Conor McGregor to Lamar Jackson, even successfully luring Snoop Dogg and Uncle Luke to campus. “He makes sure,” says Florida Atlantic athletic director Patrick Chun, “people are talking about FAU football.”

Kiffin knows his behavior is abnormal, that it flies in the face of convention. He seems not to care. “What’s more important?” he says. “For me to bring attention to this university so that I’m doing a good job for the people who hired me? Or for me to give you coachspeak, and not draw any attention to the university, and keep quiet so that some other athletic director or president wants to hire me? … I’m worrying about what I’m doing here.”

Here. Here is a small program that pays him a relatively modest salary in a Group of Five conference with few players likely ever to reach the NFL. Here is where Kiffin insists he is reevaluating his own sense of what he wants from his career.

“This place,” Kiffin says, “has changed me.”

He’s 42 now. His face has swelled, his forehead creased. His blond hair is now lined with gray. It has been more than a decade since the Raiders made him the youngest head coach in modern NFL history, nearly two decades since he first joined the staff of Pete Carroll’s early-aughts juggernaut at USC. “Back then,” Kiffin says of the earlier stages of his career, “I had this drive of like, ‘How fast can I get the biggest job?’ You know? How much money can you make? You’re always chasing. There’s this grass-is-greener mentality. I don’t think most people would admit to that, but a lot of people have it when they’re younger. I did. I think a lot of people still have it when they’re older.”

Ego is the enemy.Lane Kiffin

You know his résumé, but just in case you’ve forgotten, here’s Kiffin to remind you. “Thirty-four straight wins at USC,” he says. (That was from 2003 to 2005, during his time as an assistant under then-coach Carroll, though Kiffin doesn’t mention that USC has since vacated 14 of those wins due to NCAA sanctions over a scandal involving payments to former Trojan Reggie Bush.) “Three Heisman Trophy winners.” (Though one, Bush, had to give his Heisman back.) “Two national championships.” (One stripped.) “And we were one play away from a third.” (But, alas, Vince Young.)

He skips over the stop in Oakland, where he went 5–15 and had his firing announced in a ranting and vitriolic press conference by then-Raiders owner Al Davis, who called Kiffin a “liar” and said he “disgraced” the franchise. Among his alleged offenses: blaming ownership for the team’s struggles, leaking to ESPN an angry letter that Davis had written him (which Davis then put on an overhead projector for the press to read), and lobbying for his father, Monte, to be defensive coordinator rather than Rob Ryan. Davis accused Kiffin of trying to get fired and said that he had made the iconic owner “embarrassed to watch” his team play. In a sport famous for its bizarre press conferences, this one ranked among the most absurd.

And just like that Kiffin was off to Tennessee, hired to replace Phillip Fulmer and return the Volunteers to their former glory. He arrived in Knoxville and talked copious amounts of shit about the rest of the SEC — accusing then Florida coach Urban Meyer of recruiting violations, reportedly telling receiver Alshon Jeffery that if he went to South Carolina he’d end up pumping gas, and telling Saban (as Kiffin recounted to Clay Travis last month), after Alabama narrowly beat the Vols by blocking a potential game-winning field goal, that Saban would never beat him again. He won the hearts of Vols fans. He infuriated the rest of the league. And then, after winning a mere seven games, he was gone again, off to become head coach at USC.

Tennessee fans had loved him, but he’d left them, and as he made his way to Southern Cal, he left Knoxville engulfed in an actual riot. That night, Kiffin’s father, the Vols’ defensive coordinator, hid in the football complex, afraid to go outside, former Vol Eric Berry recently told the Chattanooga Times Free Press. “He was in a panic,” Berry said. “He wasn’t going to leave his office until the fires were out. And he didn’t. I think he slept there all night. I finally had to tell him, ‘Coach, they’re not going to do anything to you. It’s your son they’re after.’”

Kiffin told Knoxville media that he was leaving Tennessee for his dream job, the only place in the country that could ever coax him away from Knoxville. That rationale hasn’t changed. “It was my dream, absolutely,” Kiffin says. “I had these wonderful memories of being there. It was basically where I got my start. All three of my kids were born in California. I was there from day one with Pete Carroll. So I saw for six years how he did everything. So for me, if I was with him, and I know all those things, why can’t I go and do the same thing? And I know we would have.”

But he inherited a Trojans program on the brink of NCAA sanctions for Bush’s receiving payments from agents. The football team lost 30 scholarships over three years and was ineligible for postseason play for the 2010 and 2011 seasons. “We got there and thought we were going to lose maybe one or two scholarships,” Kiffin says. “But it was basically the death penalty. And we were supposed to win just like we won before. But if we hadn’t had those sanctions we’d still be there and we’d have won a ton. We’d be winning championships.”

After USC went 10–2 in Kiffin’s second season, the Trojans entered 2012 ranked preseason no. 1, led by star quarterback Matt Barkley and receiver Marqise Lee. The Trojans woefully underachieved, though, finishing 7–6 and becoming the first preseason AP no. 1 to end the year unranked since 1964. When USC started the 2013 season 3–2, Kiffin was fired that September.

There’s this perception that everything ends badly, no matter what. Well, no.Lane Kiffin

“I thought it was completely unfair,” Kiffin says. “I still do. Because of the sanctions. What did you expect us to do without 30 scholarships?” In college football lore, that moment has become famous less for the fact that USC fired Kiffin than for the way in which the school did it. Late one night after a 62–41 loss at Arizona State, then–athletic director Pat Haden pulled Kiffin off the team bus and told him the news, leaving him on the airport tarmac while his players rode back to campus. Kiffin, though, carries no resentment over the circumstances surrounding his firing, only around the firing itself. “That’s a situational thing,” he says of being left on the tarmac.

He explains that Haden had made the decision to fire Kiffin but wanted to wait to tell him until they returned to Los Angeles from Arizona. “Everyone says, ‘He was fired on the tarmac!’” Kiffin says. “But would it have made a big difference if they waited the 20 minutes to drive back to campus? No, not really.”

It wasn’t the when or the how that mattered to him; it was the reality. He’d reached the highest levels of coaching at 31 and had landed his personal dream job at 34. And then he lost it at 38. “Most successful people,” he says, “do it differently than I did. I did it backward. I was making my learning mistakes on the national stage instead of the other way around. Look at Coach Saban. He started at Toledo. Look at Urban Meyer. He started at Bowling Green. They made mistakes at those places, and they did things a lot differently than they do them now, but nobody knew. It wasn’t getting blown up everywhere. They were allowed to make mistakes and learn.”

He looks back on his early opportunities with a mix of gratitude and wistfulness. “It’s a very hard situation for anyone to handle,” Kiffin says. “Ego is the enemy.” He points to people across all fields — from wunderkind corporate executives to Hollywood child stars — who struggle to handle praise and attention and power at too early an age. Once the praise and attention arrived, he says, “It [was] hard to go back and work the same way, as hard as I did the first day I got [there]. And I really don’t think I was as bad with that as I could have been, but there was some of it, definitely.”

He seems caught, at times, between blaming the sanctions and his own lack of experience as the reasons for USC’s struggles. But when asked if he wishes his career had a more traditional trajectory, he says no. “Everything,” he says, “happens for a reason. You have to look at it and say, ‘What an unbelievable experience to be at those places in those positions at that age, and to have the chance to learn.’”

At 38, Kiffin seemed like he might never coach again. But in January 2014, after Alabama offensive coordinator Doug Nussmeier left Tuscaloosa for Michigan, Saban offered him the opportunity to do exactly what he’d done as an assistant at USC: run the offense for a defensive-minded head coach, as part of one of the great dynasties in college football. “I thought, well, I probably won’t get a head-coaching job, but it will be easy to get an offensive coordinator job,” Kiffin told reporters after his first season at Alabama. “The phone wasn’t ringing. And he called. He took a chance.”

When I was caught up in trying to chase bigger and better jobs, I never really stopped and enjoyed the moment or the process. I would never savor it.Lane Kiffin

In Kiffin’s first season in Tuscaloosa, Alabama set school single-season records in total offense, passing yards, passing touchdowns, and total touchdowns. The Tide opened up their offense, unleashing quarterback Blake Sims and spreading the field to make stars out of Amari Cooper, O.J. Howard, and, later, Calvin Ridley. Alabama won three straight SEC titles and won the national championship in 2015. Kiffin accepted the FAU job last December. He initially agreed to stay in Tuscaloosa through the end of the College Football Playoff, but the responsibilities of his next job took him away from the Tide, according to reports, and after Alabama’s offense struggled against Washington in the semifinal, Kiffin left early, reportedly at Saban’s urging. At the time Kiffin left, Alabama had won 26 straight games. Without him, the Crimson Tide lost 35–31 to Clemson.

Despite the bizarre exit, Kiffin calls his relationship with Saban “good,” and says that while Saban never returns his texts, he doesn’t take it personally; Saban doesn’t return anyone’s texts. He is aware, though, that the way he left Tuscaloosa did nothing to quell the reputation that follows him. “There’s this perception that everything ends badly, no matter what,” Kiffin says. “Well, no. At USC, that was just the situation. At Tennessee they were upset because things had been going so well. It would have been bad if they had a party when I left. At Alabama we won 26 straight games. I got a chance at a head-coaching job, and I took it. That’s it.”

He took a $450,000 annual pay cut to come to FAU, taking over a program coming off of three straight 3–9 seasons under former coach Charlie Partridge. “We were in a position where we felt like everything in our program was going right except for on Saturdays,” says FAU’s Chun. “The recruiting was good. The performance in the classroom was good. But we couldn’t risk another 3–9 season.”

Kiffin says his experience at FAU has been transformative. “It’s this sense of figuring out what I’m really doing, why I’m really coaching,” he says. “I’ve been at all these places, whether it’s Alabama or Tennessee or USC, where there’s so much that goes into it besides just coaching the players. Now, all of a sudden, I’m in a place where I show up to a press conference and there’s only four reporters there. And people wonder, ‘Is that humbling for you?’ Well, no. No, it’s not. It just takes away all the stuff that you didn’t realize you were doing just for yourself.”

If he registers the irony here, given the way he’s managed to stay in the press even from college football’s hinterlands, he doesn’t mention it. And he does seem genuinely thrilled with the realities of the job he now has. “It’s not about the money,” he says. “It’s not about the attention. It brings your focus back to them — back to the players.”

It wasn’t just the small stadium and smaller press conferences, the less-opulent facilities and the less-lucrative paycheck that struck Kiffin as unlike anywhere he’d coached before. More than anything else, he noticed a difference in the players. “There’s this appreciation of winning that you can feel,” Kiffin says. Owls players didn’t know what to think when they heard Kiffin would be their new coach. “It was weird,” says quarterback Jason Driskel. “I’d heard a lot about him but didn’t know what to think. I just knew I wanted to give him a fair chance, and ever since he got here, he’s been great.”

After losing three of its first four games, FAU has won nine straight. When the streak picked up steam, Kiffin says, “Every single week the locker room felt like we had just won the Super Bowl.” In this, he points not to the fact that most of his players were low-level recruits, but rather to the fact that none of them had experienced success at the college level. “If you go to an orphanage and give a kid a present,” he says, “and you look at the reaction on the face of that kid, and you look at the appreciation of that present, versus the rich kid that’s getting 20 presents, you see a huge difference.” Here, he’s comparing the experience of winning a conference title at FAU to doing so at USC or Alabama. “So even though the present is the same thing — a championship — it’s a totally different appreciation.”

He finds, too, that the dip in talent level changes the stakes of the college season. Even though Alabama was playing on the sport’s grandest stage, many Tide players believed their time in Tuscaloosa served as a path toward their ultimate goal of playing in the NFL. Barring a recruiting boon, few FAU players will get that chance. “At Alabama, USC, Tennessee, for a lot of those guys, they’re gonna be on another team someday,” Kiffin says. “This isn’t it for them. These guys, on senior day, they know they’re never going to play football again after this year. It’s almost like — and this is gonna be a strange analogy to make — when you tell someone they have six months to live, it’s gonna completely change what they’re doing and how they’re thinking. I think there’s something to that here. The deadline triggers the process.”

Kiffin sees the contract between player and coach as fundamentally different from at bigger programs. At places like Alabama and USC, he says, “it’s almost like this bargaining kind of agreement that you’re making at those places. It’s more of a deal. We’ll help you get what you really want, which is to get drafted as high as possible four years from now.”

Kiffin has kept his name in the news over the last few weeks of the season, not only for the work he’s done to give life to the Owls program, but for the ways he’s injected himself into college football’s coaching carousel. All through the disaster of Tennessee’s coach search, there was Kiffin, reveling in some Vols fans’ lust for his return, getting shit-talked in his DMs by former Vols quarterback Erik Ainge, and lobbying for his former colleague Tee Martin to get the job. The UT search even found its way into FAU’s football meeting room. When Kiffin showed up late one day, he joked to his players, “Sorry, guys, I was on the phone with Tennessee.”

Kiffin’s boss has no issues with his coach’s social media habits. “Lane’s an innovator and an original,” Chun says. “He does things at his own pace, his own beat. You look at his brilliance, and it comes from the fact that he unapologetically is who he is. He has the results to back up the Twitter.” Kiffin bristles at the notion that his tweets should affect his reputation as a coach or his suitability for this or any other job. “People say, ‘He’s an unsafe hire,’” Kiffin says. “Because I’m retweeting things? Really? We’re not talking about NCAA violations. We’re not talking about criminal activity. We’re talking about doing things that bring attention to a university so that I’m doing my job for the people that hired me.”

That’s true. And yet, Kiffin does have a history of working at programs eventually hit with NCAA sanctions, both as an assistant at USC and as head coach at Tennessee, though the violations and penalties at UT were minor. And in putting together his staff at FAU, he hired as offensive coordinator Kendal Briles, the former Baylor assistant (and son of former Bears head coach Art Briles) who a lawsuit alleges contributed to a culture that led to the cover-up of many acts of sexual violence by football players. “Do you like white women?” Briles once asked a prospect, according to the suit. “Because we have a lot of them at Baylor and they love football players.”

Kiffin has told reporters that he focused his decision on Briles’s coaching abilities and deferred to the university on vetting the “other stuff.” The decision has drawn criticism from many, including rape survivors’ rights activist Brenda Tracy, who speaks often to college football teams and has said repeatedly that Briles and other former Baylor coaches should no longer have jobs in coaching.

When asked about the Briles hire, Chun says, “The Baylor situation is very public. Or as public as Baylor is willing to make it. We understand the gravity of what happened there. We’re a campus with no tolerance for sexual assault. We talked with the president and the board of trustees. We made a decision based on what we had at the time.”

Under Briles and Kiffin, FAU has averaged 39.8 points per game, ninth in the country.

You look at his brilliance, and it comes from the fact that he unapologetically is who he is. He has the results to back up the Twitter.Patrick Chun

If the Owls keep winning, eventually, it seems, a bigger program will come calling for Kiffin. Many were shocked that Tennessee never turned its attention toward him, eventually hiring his former colleague, Alabama defensive coordinator Jeremy Pruitt. “I’ve been in this business long enough to know the market is heavily skewed toward coaches with a track record of success,” says Chun. “If and when the market calls, it calls. But because he’s an original, and he’s off-beat, I think this is a great fit for him at this juncture in his career.” Given that he openly jokes about taking other jobs, Kiffin has no need to offer platitudes affirming his commitment to FAU. He does, though, insist that this job has changed the way he thinks about the arc of his own career. “When I was caught up in trying to chase bigger and better jobs,” Kiffin says, “I never really stopped and enjoyed the moment or the process. I would never savor it.”

He’s finding moments to savor now. He tells a story about a photo. Before this season, Kiffin says, he declined to have the Owls take a team picture. He found it pointless. “I want to earn any team picture that we take,” he says. “I don’t want us taking a team picture unless there’s a trophy in it.” He points to his wall, where there hangs a photo of his Alabama title team at the White House with President Barack Obama. “I want it to be like that.”

But after the Owls finished their 41–17 conference championship win over North Texas, after the players doused Kiffin with Gatorade and hugged and cried with one another and their families and fans, reveling in the reality of what they’d done, Kiffin ordered the team together. He wanted a photo. The players gathered in the end zone, white jerseys dirtied, some of them lying down, and took the first photo of themselves all together this year. “We might have been on the field for an hour by then, partying,” Kiffin says. “Because we’re going to enjoy this. We’re going to enjoy taking that team picture in the end zone. It’s fitting to me. They’re sweaty, dirty, and they’ve earned it, and now they get to enjoy it.” Tonight they’ll have an opportunity for perhaps one more team photo, playing in their first bowl in nearly a decade, back on their home field.

In years past, Kiffin says, he never lost himself in those moments, never succumbed to the all-consuming joy that accompanies an accomplished goal. “Now I think different,” he says, “and I coach different, and I talk to these guys different. I just tell myself, ‘Enjoy the run you’re in.’ Winning 34 straight or 26 straight, that’s special, and I didn’t fully enjoy it for what it was. This is special, too. And now I’m enjoying it for what it is.”