In winter, the Tilly Jane A-frame house in Oregon’s Mount Hood Wilderness stands in the forest at the end of a 2.7-mile trek. In summer, it’s a mere quarter-mile walk from a campground parking lot on the northeast side of the region. But the road up there closes when the weather starts to deteriorate in the fall until, typically, June—hence the hike. When I reserved the cabin, I hadn’t read these details, which is how I came to find myself snowshoeing up Ghost’s Ridge in the dark, in search of the perfect, cozy, Instagram-friendly A-frame.

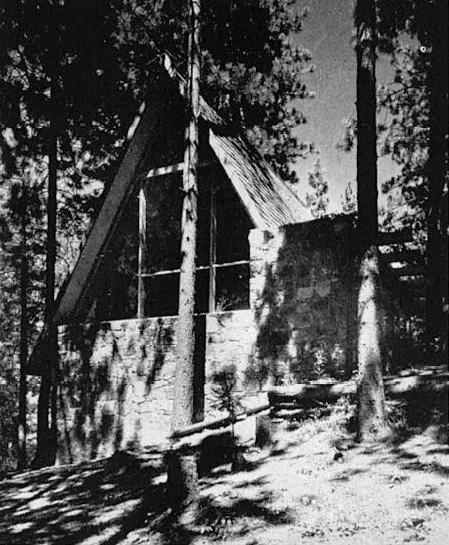

The 1,152-square foot cabin sits at 5,900 feet above sea level, just below Mount Hood’s north peak. Though it was wasn’t recognized as part of the Mount Hood Wilderness until 2008, the historic Cloud Cap region has been a popular camping locale for years, and the various shelters in the area have been frequented by those on shorter overnight hikes as well as groups preparing to summit the mountain. Tilly Jane is a picturesque example of the A-frame style: a triangular house with a steep-pitched roof, whose two sides touch the ground. A fire in 2009 threatened the cabin 70 years after its initial construction, but it was preserved and, in most respects, has been well kept. It cuts a striking image, with its massive front beams touching the ground, surrounding an already imposing entrance. Surrounded by linear trees and sitting on top of rolling snowdrifts, it is a near cliché of the idyllic A-frame image that fuels thousands of Instagram posts.

I have always loved the A-frame style, and I am not alone. A-Frame Instagram lies adjacent to #VanLife, the tiny house movement, and Camping Instagram. The symmetry and simplicity of the style make for photos of magical, seemingly impossible remote locations. The A-frame was once so popular, the style was abandoned after it reached saturation. But it’s having a revival—or, at least, a renewed appreciation on social media platforms like Instagram and on home-sharing services like Airbnb.

Despite this internet popularity, the build itself could very well remain something of a rarity—because it seems that no one is all that interested in making any more of them. The A-frame is destined to enter the nostalgia machine—visually treasured, but existing entirely within the confines of our screens.

One of the first A-frame homes in the United States was something of a mistake. That was the Bennati cabin, built in the 1930s when homes were erected in the newly developed Lake Arrowhead area of California. Architecture historian and Lake Arrowhead vacation home owner Diane Wilk told me the lake was originally built in 1893 as a water supply for orange farmers in San Bernardino. In 1905, the property was transferred to the Arrowhead Reservoir and Power Company, also based in the burgeoning area. Then in 1912, a court decision stipulated that the water supply couldn’t be sold to any vendors outside the natural watershed, lessening its value to the power company, and so it was sold to another company in the water industry, Arrowhead Lake Company (fronted by L.A. businessmen J.V. Van Nuys and John O’Melveny). It was then that the lake and surrounding area became known as Lake Arrowhead. More houses were constructed, and the golf course was built. A vacation destination was born.

Later, in 1946, the Los Angeles Turf Club bought the lake for recreation and formed a committee to build a village surrounding it. The style they decided on was French Norman.

Rudolph Schindler was hired to to design the Bennati cabin, but he didn’t care for the French Norman style. The Austrian-born architect had cultivated a distinct reputation in the Los Angeles area with projects like the Laurelwood Apartments and the Bethlehem Baptist Church. He was influenced by styles of his home country, but with a penchant for modernism. He was interested in Frank Lloyd Wright and had even worked with the famed architect. He decided to create a variation on French Norman, and thus the A-frame came into existence. “The Bennati cabin is credited as the world’s first A-frame,” says Wilk, who adds that it’s still standing up on a winding dirt road in Lake Arrowhead. “It burned partially down in the ’60s or ’70s, but the owners rebuilt.”

The style influenced the rest of development there; subdivisions today still feature a variety of A-frames. “It became the de facto style of Lake Arrowhead,” Wilk says. “There are all kinds of versions of it.” The Lake Arrowhead Country Club, built in the 1970s, purports to be the world’s largest A-frame. The style enjoyed a steady rise during post–World War II boom, becoming popular during the ’60s. And then they began to fade out during the ’70s.

The de facto A-frame expert, Chad Randl, explained this climb to popularity followed by its decline. His book, A-Frame, is an encyclopedic, historical look at the design and its influence. Randl was a graduate student studying historical preservation at Cornell University, browsing vintage Sunset magazines that a professor had left behind in the student lounge when he saw articles on A-frames. “I was interested in exploring a building type that had experienced that sort of boom and bust, that rise and fall,” he tells me. “And I wanted to use it as a tool to learn why we have these love affairs with a building type. You see them all over the place, and then they almost as quickly bust.”

Since California’s A-frame boom came immediately following World War II after Schindler’s first design, the economic upswing meant more and more people could buy second vacation homes. “All these reservoirs were being created so there was new lakefront property,” Randl says, which is why A-frames dot the land around reservoirs and lakes in other areas, like Squaw Valley and beyond. “With second homes, you can be a little looser, you can be experimental,” he adds. “You can play with ideas a little more and you don’t have to worry about being so conventional or fulfilling all the requirements of a house you live in year-round.”

There were a few other factors that led to the A-frame trend. The modern skiing aesthetic took off, too. “After World War II, all these soldiers came back after spending time in the Austrian Alps and in Bavaria during the occupation. And you have guys coming back and starting ski schools, so there was all this interest in Alpine architecture,” Randl says. The mountain chalet style that influenced Schindler also influenced a new American generation, and, as a bonus, A-frames were easily identifiable. It’s the sort of look you can reference: “Take a right at the A-frame” or “the triangle house at the end of the street.”

Home construction companies seized the moment. Lindal Cedar Homes was one of them. The company was started in 1945 by Sir Walter Lindal (it’s now run by younger generations of the family), and it has sold more than 50,000 homes, largely to clients on the coasts of Canada and the U.S. The buyers would construct the units themselves, based on Lindal designs and using pre-cut lumber and plans. “These were single-wall constructions—back then, you could buy a building package for $3,500, $4,000,” says Lindal VP of marketing Sig Benson. “When I figured that out I thought, ‘Oh my, that’s crazy!’”

According to Benson, the Lindal A-frame hit its peak popularity in the ’60s. Sir Walter Lindal introduced a new patented version. The model opened up the home a bit wider with a less steep pitch, and over time, customers started making their own modifications. The most notable change was adding dormers—a lofted space on the second floor that would pop out and create an area where people could stand up, though interrupting the perfect triangle on the inside. The adulterated version introduced more floor space and big windows, but also hastened the demise of the style. Usable floor space was more important than the perfect triangle.

Another culprit was the high cost of heating and cooling. “Insulation was part of it, because the early ones were built without any sort of insulation,” according to Randl. Plus, A-frames simply went out of style. “I think what’s just as potent is the fact they just sort of had their run,” says Randl. “Just like bell bottoms or paisley … at a certain point they lose their novelty.”

Lindal Homes no longer makes its original A-frame. Benson adds that customers prefer flatter roofs.

The demand to build new ones never bounced back. Collyn Wainwright is a Nashville-based realtor who re-entered real estate in 2014 after the 2008 crash. She’s been a longtime admirer of the style, but doesn’t see many of them on the market. “I see great ones sit for sale when our market is hot with low inventory,” says Wainwright. “They often need a lot of work, so they get passed over for the ranch a few streets over.”

It isn’t difficult to find stories about renovated A-frames, but trends indicate that despite the tiny-house phenomenon, American homes are still increasing in size. And while there’s been a small rise in single-family housing builds (after a massive crash), and multi-family units have experienced a small drop, structures like apartments, condos, and their ilk continue to dominate new construction. Metro areas are desperately in need of new housing, but the dramatic situation in these places requires a large-scale solution. This is not the climate for new A-frames.

Though A-frames are best suited for snow-bound areas, they became popular in the tropics and a symbol of leisure. An issue of Popular Mechanics from April 1966 features a spread on the Lindal Homes in Toronado and Barracuda, nestled next to palm trees and aside the jewel-blue ocean. “‘Lincoln Logs’ lodge even faster” the magazine proclaims above an image of a bathing-suited family traipsing across the deck of their jungle A-frame. The story goes on to say that the vacation homes are perfect for the slopes or seaside, of course, but the message consistently is that these are the homes for your holidays. “Dreams? Today, the dream of a vacation home is coming true for millions of families,” Walter I. Fischman writes in what is clearly an early version of sponsored content. “In every vacation area throughout the country wild and wonderful homes are popping up in a kaleidoscope of styles and sizes that share some enticing basic features: they’re relatively inexpensive, easy to maintain and can be used the world year ’round.”

Thanks to marketing like this, A-frames became a status symbol while remaining affordable, a notion reinforced today by the internet. Instagram is an A-frame addict’s gateway, as it overflows with almost-too-symmetrical window shots that look out onto snowy hillsides, or images of the houses plopped in the middle of a beach or forest as in Popular Mechanics. And then you can move on to Airbnb, Pinterest, and Hipcamp. When you dive in, you will start to pick up on a few themes: surreal surroundings, golden hour light, rustic interiors, clean lines, good linens. Perfect but not too perfect; lived-in.

The triangle-shaped homes are at once a braggable acquisition and a return to simplicity. Wilk suggests some of our renewed interest could be thanks to the Ikea-ization of our homes. “It is very simple and elegant and yet it also alludes to something basic. It’s the primitive hut; it gives you illusions of a house without being traditional.”

The A-frame’s storming of social media coincides with the prevalence of the Danish “hygge” trend, which, if you’ve missed it, is a concept that amounts to cozy and charming, but has come to define an entire genre of home goods and Instagram posts. And while it defies the hallmarks of hygge, the Kondo minimalism craze shares some aesthetic elements with A-frames. Combined with the mass movement by amateur photographers to capture and share the outdoors, it’s hardly surprising that the A-frame has found internet fame. The wildly popular @cabinporn, @thecabinchronicles, and @cabinlove Instagram accounts (among others, like the more specific @aframecabins) feature house after house, and they’re among the most in-demand homes on Airbnb.

Anais Verger lives in Switzerland, but she rents out an Airbnb A-frame in the Philippines. The 30-year-old bought land three years after falling in love with the island. “I’ve always loved the A-frame style and I’ve been studying [it for more] than a year, documenting my research on Instagram, Pinterest, and [other websites],” she says. She designed her property herself, combining the traditional chalet look of most A-frames with tropical elements. After four months of designing, she bought the materials, hired workers, and construction began. She started renting it November 1 of this year. It’s fully booked until the middle of March 2018.

Kara Van Dyke understands the attraction—and monetary value—of an A-frame. Her grandfather built one in Heber Valley, Utah, 30 years ago. Van Dyke remembers going there as a child. “He had an eye for design and built the cabin as a place of solitude. He would often go there to write music and meditate.” Later, she contributed to renovations as well, and even lived in it for a short while. Then, she says when “life happened,” she moved out and “on a whim and out of desperation” put it on Airbnb. She says within 12 hours, the home had three bookings. “It hasn’t slowed down since.”

A single mom to two boys, Van Dyke’s full-time job is in marketing, but she—and her A-frame—have stumbled into a small bit of internet celebrity. She refers to the home as A-Frame Haus on her website, Airbnb, and Instagram, where it has over 11,000 followers. Guests document their stays and share envy-inducing photos of their time there, which Van Dyke appreciates—not only from a marketing perspective, but because she treasures the home. “It’s so rewarding to share this cabin and all of the passion and hard work that went into creating it. … I hope my grandpa would be proud of what I’ve done with his little A-frame.” Van Dyke says she’s noticed something of an A-frame comeback, but of course, she’s firmly ensconced in Cabin Instagram.

For those looking to buy an A-frame, there’s a service for that, too. Wainwright, the real estate agent in Nashville, started a website that finds A-frames for sale in your state (tagline: “Finding your dream triangle”) and an Instagram account (@aframeliving) dedicated to the design. While her account is small, it has benefited from increased A-frame interest. “Yes, they photograph well, but I think a lot of the interest is born out of the tiny house movement,” she says. “An A-frame can be spacious compared to many tiny homes, yet [they] offer the same pared down lifestyle. ‘Tiny house lite,’ if you will. Younger buyers are not looking for the big suburban home, but are drawn to smaller, more efficient dwellings.” She admits that A-frames are not the most efficient use of space, but “the charm makes up for all the headaches those sloping walls can create!,” she says in their defense. “I think sites like Cabin Porn have also struck a chord and given the humble A-frame a chance to shine again.”

Travel writer Lindsey Bro runs the aforementioned, well-known Instagram account @cabinlove. She started it a couple of years ago, purely out of her own fascination with the structures and the places they’re in. “I basically put together a whole bunch of photos I’d had forever, and it immediately started to grow,” she says. “I think, because of the cabin aesthetic or that people are drawn to the small structures, or whatever it might be, there’s a longing people have for these places—but I also think people just want this sense of escapism.” She says she often sees people tagging friends in the comments, showing them these fairy-tale-worthy places. “They’re saying, ‘Hey, this is it! This is that little dream that we have, that we work Monday through Friday for. We can go and escape to this!’”

Eventually, @cabinlove followers started submitting their own photos to Bro, and now the account is a mix of her own images—she estimates one-third are hers—and those from other users. “I’m building out the website now because I feel like people want to—well, I want to—know the story about the people who are behind these places and the areas that they’re in and why they built it and how they built it,” she tells me. “So I’m more focused on the storytelling side of it now rather than just the visual side of it.”

She, of course, has noticed that a great many of the photos on @cabinlove—her own and others’—are A-frames. “If you’re looking at it in a visual sense, it is a striking silhouette that it cuts. You’re already in a forested area so you have the trees going vertical, and then you have these lines of the A-frame that are cutting against it. There’s just this beautiful line it creates.”

Bro and I agree that A-frames elicit a nostalgia that lacks a reference point. They’re evocative, but no specific memories are necessary. “This is a very visually driven time,” she says. “There’s a sort of commoditization of content and experiences,” and A-frames aren’t exempt.

“We’ve romanticized and practically fetishized the idea of building humble rural retreats,” Diana Budds wrote in a FastCompany’s Co.Design article about the internet commoditization of the cabin earlier this year. When taken to its extreme, this mentality can bend us into living spaces that all look the same—Kyle Chayka wrote about this issue, noting that “the ideal Airbnb is both unfamiliar and completely recognizable.” A-frames can certainly fall victim to this problem, a beloved form becoming little more than a stage setting for weekend visitors and their photo shoots, and momentary Instagram-happy wanderers. This affection likely won’t yield a new crop of A-frames. There is, instead, just a slightly sustained-yet-passing appreciation for the ones we happen to notice.

The morning I woke up after hiking to Tilly Jane is when I was finally able to see the A-frame. Its charm immediately became apparent in daylight: The ring game was attached to the ceiling with handwritten instructions, and there was a tiny beer-pong set near the “kitchen”—an assemblage of pots and pans. Drawings of the cabin were pinned to a bulletin board, and an ancient set of cross-country skis hung on the wall for decoration. Outside, it was snowing and silent and deserted. To interrupt such a landscape would be a travesty, but the A-frame blended in; it was the only structure, I realized, that made sense there. And, of course, it made for some Hygge-inducing Instagram photos. But I like to think that was just a bonus.