The Harvey Weinstein exposés have changed the way Hollywood thinks about sexual harassment and assault. But they’ve had another side effect: They’ve changed the way Hollywood’s editors and reporters think about their beat. The normal industry fare — the signing of a deal, “10 things we learned from the Last Jedi trailer” — has given way to a frantic chase to expose the depredations of the Next Harvey (or the further depredations of the current one). Publications and sites have undergone a kind of gritty reboot, and what was once a micro-genre of reporting has become the main event. Welcome to Entertainment Writing: SVU.

The Hollywood Reporter — home of the awards-season roundtable — now has seven reporters working more or less full time on the post-Harvey beat, according to Matthew Belloni, the magazine’s editorial director. Belloni said that “about 50 percent of my time has been pursuing, managing, making decisions on, evaluating, and publishing these kinds of stories.”

Nearly every reporter at Variety is chasing stories about Weinstein, other accused predators, or the resulting fallout. After The New York Times broke the first Weinstein story, the trade paper’s phones were so deluged with Harvey stories that they had to turn the calls over to the interns.

The writer Kim Masters, who broke the story about sexual harassment charges against Amazon Studios’ Roy Price, compared the race for scoops to competition between The New York Times and The Washington Post for Trump news. It is fierce but collegial in pursuit of a common quarry. When she gets beat, Masters said, “I’m not as miserable as I’d normally be.”

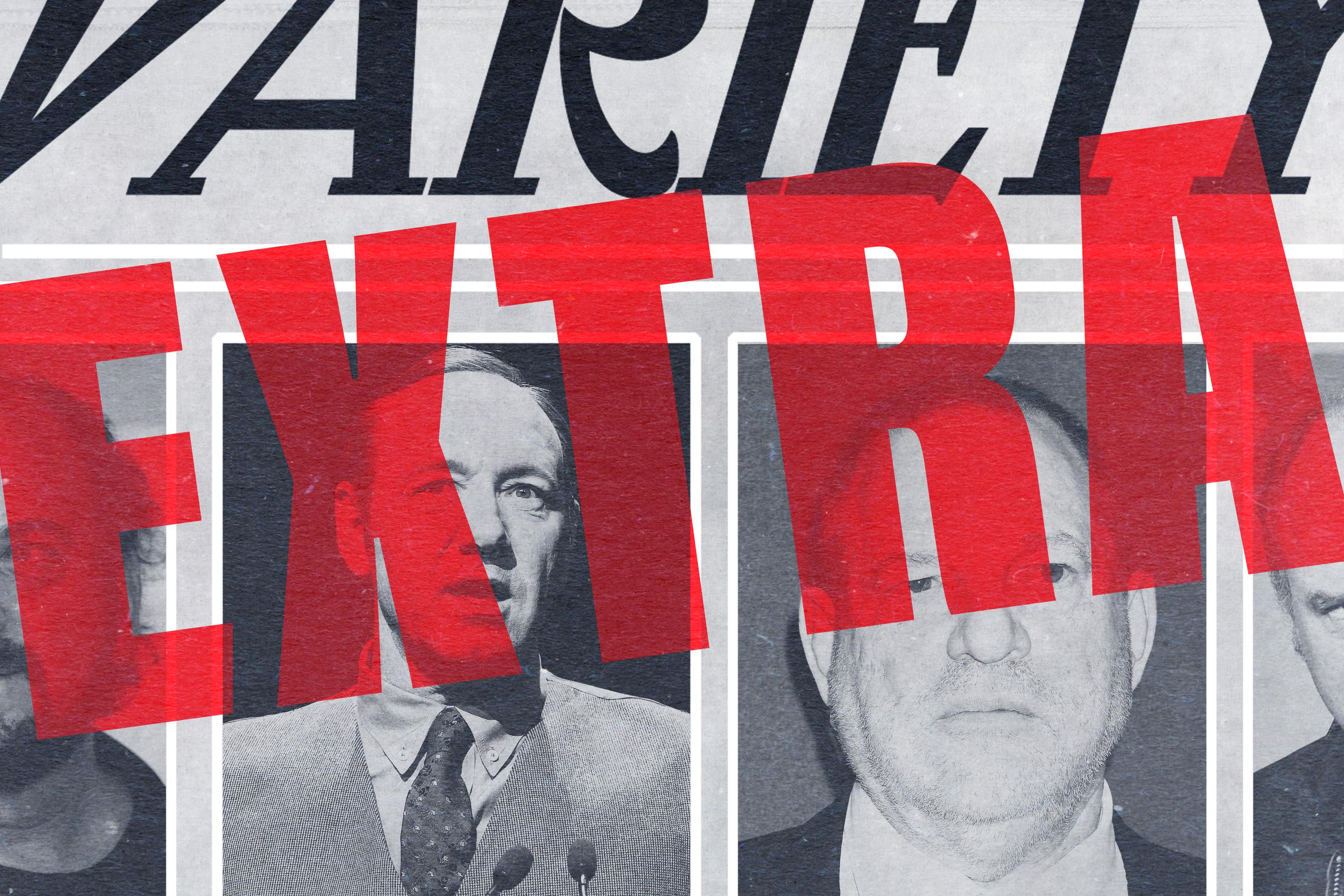

Publications left out of the initial flurry have rallied to get back in the game. Last month, BuzzFeed changed its top entertainment editors due in part to what one editor called “holes in our Weinstein coverage.” Days later, the site broke the news that actor Anthony Rapp was accusing Kevin Spacey of “making a sexual advance” when Rapp was 14. The Los Angeles Times, which sat out the early innings, has since published investigations about directors James Toback and Brett Ratner. “The entertainment staff has basically been turned into a metro department,” one arts writer said.

A mere two months ago, Twitter waited like a cargo cult for the nightly political news drop from Maggie Haberman and Glenn Thrush. It now awaits the latest gruesome allegations about Louis C.K. Or Matthew Weiner. Or Jeffrey Tambor. “Even on a day like today, when the Louis C.K. story breaks, I know a couple of journalists who are already working on the next one, and have been working on it for weeks,” said the entertainment writer and author Mark Harris.

“It’s almost making us feel like political reporters that cover the Trump campaign,” said The Daily Beast’s Marlow Stern, who got George Clooney’s first comments about Weinstein. “Every day there’s more insanity, and every day there are new revelations.”

The transformation of the Hollywood beat began on October 4, the day before The New York Times published its first Weinstein story. Three Variety reporters, Gene Maddaus, Brent Lang, and Ramin Setoodeh, heard rumors that the Times and New Yorker pieces were close to being published and called Weinstein’s PR handlers. Puffed up with bravado, or maybe denial, Weinstein agreed to an interview. He played dumb — “I don’t know what you’re talking about, honestly” — and said he was editing a new movie, The Current War. Maddaus recognized this was how Weinstein liked to plug his upcoming movies.

After the Times story broke, Maddaus began working 12- to 14-hour days chasing the story. The beat’s metabolism has changed. Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey took six months to report and write their first Weinstein story. Such a piece “is now a two-week investigation,” said Maddaus, “because of the competitive pressures around it and because people are willing to come forward in a way they weren’t before.”

Big-scale investigations bring both prestige and traffic. On Thursday night, The New York Times’ Louis C.K. investigation was the paper’s most-viewed story, with a Lindy West column about sexual assault and harassment in the no. 2 slot. Stories about Senate candidate Roy Moore’s advances on teenage girls and swimmer Diana Nyad’s sexual assault were in the top 10.

Just about every Hollywood reporter now finds themselves deluged with rumors. Richard Rushfield, a longtime entertainment writer who edits the newsletter The Ankler, reeled off a few: That alleged predators have been assembled in a Google Doc — a Shitty Media Men of Hollywood — that can be accessed only by female executives. That the next star to be accused won’t be a known creep but a “nice guy” that will shock the world. “This is the biggest story to rock Hollywood,” Rushfield said, “with its many implications and everything else, since the blacklist or before.”

The publication of a first wave of muckraking is only the beginning. In true Hollywood fashion, there are sequels. After Glenn Whipp reported on James Toback’s alleged serial harassment in the L.A. Times, more accusations against Toback were lodged by Rachel McAdams and Selma Blair in Vanity Fair, Julianne Moore on Twitter, Natalie Morales on Access Hollywood, and Guardians of the Galaxy director James Gunn on Facebook. Each was a reportable or at least aggregatable story all by itself.

Every revelation also raises the question: Who else in Hollywood knew? When The Daily Beast’s Stern talked to Clooney, it was four days after the Times’ initial Weinstein story, and after Ben Affleck and Matt Damon had issued mealy-mouthed statements. Stern noticed that Clooney called him directly rather than using the usual patch-through with the publicist. Get me on the record, stat!

The Weinstein scandal has yielded new forms of entertainment journalism. There is the #MeToo memoir: Lupita Nyong’o writing on her harrowing experiences with Weinstein; Harry Dreyfuss on Kevin Spacey; and former film student Ilana Bar-Din Giannini on the Hungarian director Dezso Magyar. “The most effective pieces I have seen are the ones where people are telling their stories,” said Belloni.

Such stories have introduced the entertainment media to a level of fact checking that’s more common to The New Yorker. Before The Hollywood Reporter published Anna Graham Hunter’s story accusing Dustin Hoffman of harassing and groping her in 1985, when she was an 17-year-old intern on a movie set, the editors examined the contemporaneous letters that Graham wrote to her sister. They were satisfied that the letters used an older paper stock and were written in a teenager’s cursive script.

“I’d really love to know what it means to publish the Dustin Hoffman thing now versus when it was happening,” said one entertainment writer. “Is that a legal thing or a cultural thing?” The answer is probably both. And even if such a piece had survived legal and editorial scrutiny in 1985, it’s unclear whether a publication would have known what to do with it. Just as the movie industry lacked outlets for women to report rampant sexual harassment and abuse, movie journalism lacked a genre that they could use to share it.

Kim Masters pointed out that the Hollywood press is making up new journalistic rules on the fly. In one story she was working on, there was a Hollywood person who’d already been accused of bad acts on the record. Masters heard an additional allegation about him, but her source wouldn’t go on the record. “Do we go ahead and publish that?” she asked. “It’s not like the rule book is so clear.”

In another case, Masters said, she had been reporting on an actress who had pulled out of a project because of the behavior of an individual she called a “very big-name player.” Masters thought she had the story cold, but the actress hadn’t responded to her requests for comment. Should Masters publish the story and drag the actress into it unwillingly? She wasn’t sure.

“Classes are going to be taught on this, I suppose, someday,” she said. “But right now, we’re in a laboratory figuring it out.”

For years, stars regarded the Hollywood press as (at best) a necessary evil. Now, they praise its pluck and resourcefulness. After Ronan Farrow’s latest New Yorker bombshell, Jessica Chastain tweeted, “Now this is why journalists are heroes.” Ashley Judd, who went on the record in the Times’ first Weinstein story, wrote, “Voice matters. Narratives can change structures. Journalism works.”

Even more promisingly, actors have encouraged victims to bring their stories to the media. Olivia Munn, who said she’d been harassed by Ratner in 2004, advised readers that Amy Kaufman, a reporter at the L.A. Times, had her DMs open. In October, Selma Blair sent a message to Scott Derrickson, the director of Doctor Strange, saying she’d been harassed by Toback. Derrickson forwarded her tip to the Los Angeles Times’ Glenn Whipp. Within weeks, Whipp had located more than 30 accusers. A few days after his story ran, he had located more than 200.

The Weinstein story didn’t come out of a vacuum. Three years before, Hannibal Buress and Gawker resuscitated the sexual-assault allegations that had been lodged against Bill Cosby.

“I’ve asked myself this a lot,” said Mark Harris. “The Cosby story got a huge amount of attention. Why did it not open the floodgates the way the Weinstein story did?”

Harris said that while Cosby’s avuncular image allowed some fans to dismiss or willfully forget his allegations, Weinstein was basically unknown to the non-cinephile public. The first thing many people knew of him was what they heard on the news. The accusers in the Times’ initial story and follow-up and the first New Yorker story represented a huge range of women. “There’s something about the erasure of class distinctions when Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie and someone you’ve sort of heard of once and someone you’ve never heard of are all telling the same story, all describing the same feeling, and all describing the same trauma,” Harris said.

The post-Weinstein stories offer an opportunity for an entertainment writer to flex different muscles. Rushfield told me: “I’d like to believe if you spend 10 years of your life writing, ‘Here’s the first glimpse at Batman’s new hood ornament,’ or, ’10 things we learned on the set of Episode 5, Season 6 of The Flash,’ that at some point the thought would come up that this is not what I got into journalism for, and that there’s a hunger to do something more meaningful.”

BuzzFeed reporter Kate Aurthur noted that the Weinstein fallout also “gives a shot in the arm to some of these formats that are tried and true” — like the chatty movie-star profile. Now, such a profile can be about something more than the actor’s “amazing” costars; it can make news. In a recent New York Times Q&A with Michelle Pfeiffer, Weinstein was mentioned in the fourth paragraph, even though Pfeiffer never worked with the producer.

With the exception of Hoffman, Tambor, and a few mid-level agents, the people who have turned up in the investigative pieces so far were buzzed about in Hollywood for years. “It all feels like we’re still in low-hanging-fruit territory,” said Rushfield. There are rumors that reporters are working on pieces about actors no one would expect, power players whose fall would be bigger — in current terms — than even Weinstein’s.

And even after the investigations are exhausted, there’s still a question of how Hollywood — which gave Cosby a network show as recently in 2014 — will treat the accused. Masters pointed out that there’s a continuum of behavior. “I honestly don’t know at this point what I think,” she said. “Should somebody be able to come back from a harassing phone call that’s explicit?”

Rushfield has suggested a blue-ribbon commission led by someone like Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy. That, of course, would lead to more stories of condemnation, redemption, and — a Hollywood favorite — the comeback, all of which would be more fodder for the press. “I think it’s the beginning,” said The Hollywood Reporter’s Matthew Belloni. “I really do. … I have no idea where this is going to end.”