The question at the end of every season of Sherlock, and usually for quite some time before, is: When are we getting more? American TV has only just caught on to the idea of relaxed release schedules for its top performers (see: Donald Glover taking the year off from Atlanta to be Lando Calrissian). When it comes to Sherlock, the BBC has been operating under the principle of “We’ll take what we can get, when we can get it,” flexible even by British standards, for years. Hence why the show just aired the last of its fourth three-episode cycle in seven years, after the third aired all the way back in 2014.

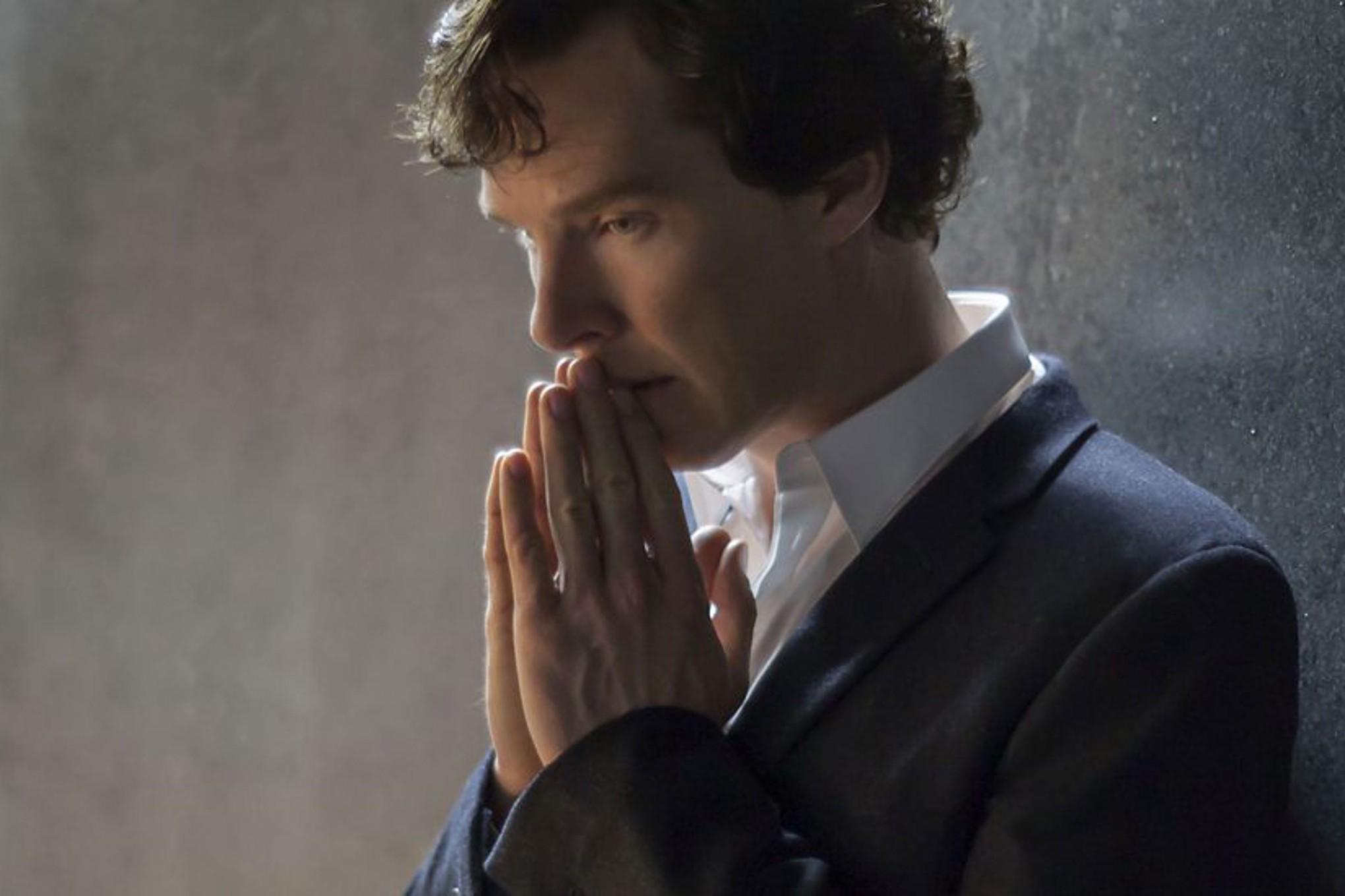

Given those sizable yet erratic waits, speculation about the timing or even existence of the next Sherlock season — which its stars (Benedict Cumberbatch, Martin Freeman) have to make time for between their day jobs as cogs in the Marvel machine — is at a permanent fever pitch. Already, cocreators Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat are giving interviews in which they hint at what they would do with a Season 5, which isn’t even guaranteed yet. We could be settling in for another few years’ worth of vague tidbits, anticipation, and, frankly, diminishing returns.

Or Gatiss and Moffat could, and should, simply call it a show. “The Final Problem” was by no means Sherlock’s best episode; that honor still belongs to Season 2’s “The Reichenbach Fall.” Since then, the show declined to definitively resolve its biggest cliff-hanger — how Sherlock managed to survive a swan dive off a six-story building — and had to figure out how to proceed without its iconic villain. But “The Final Problem,” as its name suggests, would make for a very fine series finale. And that’s exactly what it ought to be. It’s the natural inclination of TV as a business to continue indefinitely as long as there’s demand. “The Final Problem,” however, indicates Sherlock has given all it’s got when it comes to theme and character.

In the closing minutes of last week’s “The Lying Detective,” we learned that Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes have a third sibling: little sister Eurus, played with a genuinely terrifying unpredictability by Sian Brooke. If Sherlock self-identifies as a “high-functioning sociopath,” Eurus is more an out-and-out psychopath, the kind who, we learn, drowns dogs and torches the family home. Sherlock, Mycroft, and John Watson spend virtually the entire episode in a demented Triwizard Tournament of Eurus’s own design; she’s managed to take over the remote island fortress where oldest brother Mycroft has stashed her all these years, and she’s used it to create a set of mind games for the sole purpose of cracking Sherlock — getting to know him, in a twisted way, by probing his limits.

The entire plot is almost custom-designed to demonstrate the series’ late-period flaws. One is that, in the wake of Mary Watson’s death early in the season, Sherlock has exhausted the short list of characters it can kill off without tearing apart the fabric of the show. One of Eurus’s tests forces Sherlock to choose between killing Mycroft and John, and it’s immediately obvious that both will survive, because both are essential foils: Sherlock’s conscience and his cautionary tale of what he’d be like without one, respectively. What’s more, the point of the test — that Sherlock, in spite of himself, has formed real human connections he can’t overpower with pure logic — has been proved before many times over, and in more powerful ways.

And then there’s the fact none of this lands as hard as it’s supposed to, because Sherlock hasn’t had enough time to set up “The Final Problem,” nor does it have enough time to explore its fallout. In the past, Sherlock’s tripartite structure has worked in its favor, preventing the drag that can afflict American TV seasons and ensuring that individual chapters, if occasionally subpar, were at least never filler. Here, however, the revelation that there’s a third Holmes sibling who’s been plotting to entrap her brothers for years comes out of nowhere, and we’re in the thick of her master plan before the audience can absorb such a seismic shift in the show’s reality.

The episode’s final twist is even more abrupt, and even more shortchanged by that abruptness. Throughout the tests, Sherlock is tormented by a little girl on a plane full of passed-out passengers, speaking to him on the phone in an escalating panic. We learn that the girl is actually Eurus speaking in an altered voice, not a ruse so much as a split personality Eurus herself doesn’t seem to be aware of. It’s a development with far-reaching implications about a major character’s motivations squished into mere minutes. Suddenly, Eurus doesn’t seem so much sadistic as pathetic. With that subconscious cry for help — Sherlock helpfully points out that a girl on a plane is a metaphor for a mind miles above everyone else — Eurus suddenly pivots from megalomaniacal supervillain to tragic mental case. The transition would feel more earned and less clumsy if Sherlock had another hour or so to explore it. At the end of 90 minutes, it’s neat sentimentality.

“The Final Problem” is by no means a total miss; it still works elegantly as a maybe-send-off. Andrew Scott returns to give Moriarty the perfect last hurrah, Queen dance session included. There’s a goofy-as-hell explosion, witty banter old hands like Gatiss and Moffat could write in their sleep, and, courtesy of a beyond-the-grave Mary Watson, a sentimental concluding voiceover that won’t seem maudlin if it ends up being a bow placed atop a finished product. They’re all evidence of the rather high baseline level of entertainment Sherlock isn’t likely to dip below if given the chance to continue. The episode is simply an indication that, if Sherlock were to continue, its problems would only grow, while its virtues would stay the same. Sherlock Holmes has always had quite the brain. Now Sherlock’s given him a heart, and even that he’s had for a while now. He’s complete, and so is his show.