There's always room for improvement. So even though the NBA is now a 12-month league that we can’t look away from, we here at The Ringer have a few humble suggestions to make it even greater. Welcome to League Hack Week—the first of four weeklong series leading up to opening night of the 2017-18 NBA season.

Three years ago, the NBA held a vote that was meant to double as a funeral. Commissioner Adam Silver and certain concerned owners believed the league was in desperate need of lottery reform—what with Sam Hinkie and the 76ers’ audacious attempt to gain a rebuilding advantage by using established rules—and most were confident they had convened to bury the losing-to-win model once and for all.

In advance of that fateful vote, Sixers sources told me they expected the measure to pass. It did not. Before Silver could hang a toe tag on tanking, the Sixers—along with, perhaps, Thunder general manager Sam Presti and others with similar self-interests, depending on which whispers you believe—grabbed the emergency defibrillator and kept the concept alive by convincing enough small-market teams that voting for that particular lottery reform proposal would kill off one of their best ways to secure top-tier players (especially since the free-agent market isn’t always friendly). And so, much to everyone’s surprise, 13 teams reportedly voted against reform, which was enough to sink the proposal.

Today, there’s less obvious impetus to overhaul the lottery system then there was back then. The Sixers are no longer tanking, and Hinkie was sacrificed in the process of the Process—a warning to future general managers not to get any bright ideas about extreme rebuilding maneuvers. The Bulls and Hawks are rebooting, for example, but they took care not to completely Hulk-smash the reset button to pieces while doing so. In a league where the Warriors are so far above everyone else, who can blame them? Evidently, Silver and the competition committee can.

Late last week, according to ESPN’s Adrian Wojnarowski, the league’s competition committee recommended a new lottery-reform proposal that will be voted on by the NBA’s board of governors when it meets in New York on September 28. If the league gets 23 “yes” votes, the new system is expected to be implemented for the 2019 draft. According to Woj’s report, the league would seek to de-incentivize losing by adjusting the lottery odds. Under the current system, the team with the worst record has a 25 percent chance to land the first-overall pick and can select no lower than fourth. The second-worst team has a 19.9 percent chance of getting the first pick and can select no lower than fifth, while the third-worst record has a 15.6 percent shot at the first pick and can draft no lower than sixth.

The new proposal would flatten those odds, giving the three worst records an equal 14 percent chance to secure the first-overall pick. The team with the worst record could also potentially pick as low as fifth, while the second-worst record could drop to sixth and the third-worst record could fall to seventh. Additionally, odds for teams at the back end of the lottery would be marginally boosted. Part of the concern there is that the league might simply swap one set of tankers for another. Instead of teams that are already awful and try to be more awful, the league might wind up with teams on the fringe of the playoffs suddenly taking late-season dives in order to avoid a tough playoff matchup and land on a more comfortable lottery cushion.

But as far as Silver and some owners are concerned, the potential ripple effects of the new proposal are minor issues. Apparently, something simply had to be done to prevent bad teams from being bad in the hopes of one day being good enough to win more than, say, 40 games. This is super serious stuff. At their gathering, the board of governors should distribute pearls for clutching and hand fans to ward off fainting because won’t someone please think of the children?

Except the league has it all wrong. If the Warriors can unite to form NBA Voltron (and KD will be the head!), why can’t the Suns, Kings, Magic, and the rest of the would-be rebuilders fast break in a different direction? Those teams aren’t winning anything anytime soon. Losing now to hopefully win later—especially when everyone knows they’re going to lose now—makes sense. The lottery is inarguably the best and sometimes only way for small-market teams to secure quality players. From a long-term asset acquisition and competition standpoint, tanking could prove to be a smart strategy for the little guys who dream of becoming giants.

But that’s only part of why the anti-tanking push is foolish. It’s hard to imagine that this new proposal will curb tanking and polish whatever part of the NBA’s image was tarnished as a result of the approach. (More on all that shortly.) And—importantly from a product perspective—the NBA is now a year-round league. A good portion of the unending attraction is owed to the draft and summer league and trades and gossip. Tanking fuels all those things. Tanking helps make the offseason enjoyable. Tanking acts as a catalyst on interest. The offseason is the real season for bad teams. Fans of bad teams geek out on it. I geek out on it. In an admittedly weird and sometimes perverse way, tanking isn’t just smart, it’s fun. I come not to bury tanking, but to praise it.

In a smart Twitter thread, Ben Falk—former VP of basketball strategy for the Sixers—called the potential changes to the lottery structure a “mistake” and predicted they would “not have the intended effect.” You might expect one of Hinkie’s most trusted lieutenants to adopt that position, but Falk stipulated that the lottery format needs alterations and that the “current rules are too far to one side.” His underlying point was that tanking is a symptom of the current CBA, a system which creates a league of “haves and have-nots.” He argued that changing the CBA is the only way to properly address tanking. Anything else, he wrote, would be “putting a Band-Aid on a broken leg.”

“Right now, I don’t have a horse in the race and I still don’t think it’s the right idea,” Falk told me. “This is trying to fix the problem in the wrong spot. If you try to do it this way, you’ll end up creating other problems. You’re not actually solving the core issue.”

To Falk, there are two primary reasons why teams tank: 1. They need a star and 2. that’s the best way to get one. Needing a star, he said, is the nature of the game itself. “Basketball, very interestingly, is dependent on elite talent more than other sports,” Falk said. “That’s not really going to change.” That’s an important point, and not just because top-level stars are the only real way to challenge for a championship. Fans love stars too. Unlike the NFL, which lends itself to the tribalism of local fandom through the ritual of the weekly game, NBA fans can watch games nearly every night. If you live in Sacramento and you’re force-fed bad basketball with no stars, you can always change the League Pass channel and switch to a steady diet of out-of-market Steph Curry offerings.

The problem for small-market organizations is that free agency is rarely an option when you’re desperate to secure star players. Falk learned that lesson in Portland, where he served as the basketball analytics manager under Trail Blazers general manager Neil Olshey before leaving for Philly. Olshey has made lots of moves with the Blazers, but as Falk asked, “Who was the last big name that went to Portland?”

It was a rhetorical question, but my mind searched for a good answer to counter his argument. The best name I could come up with over the past five years was Evan Turner. No disrespect to the Villain, but that proved Falk’s point.

“I loved living in Portland, but we figured out pretty quickly that free agency wasn’t a method to getting a star,” Falk said. “There are a lot of teams that are like that, that feel like they’re kind of on the outside.”

Unsurprisingly, Falk has lots of ideas about how to better distribute stars throughout the league—from getting rid of the max contract to changing rookie deals—and he plans to write about them soon for his site. In the interim, he’s sure that the current proposal is little more than another “ad hoc tax on a problem that popped up.”

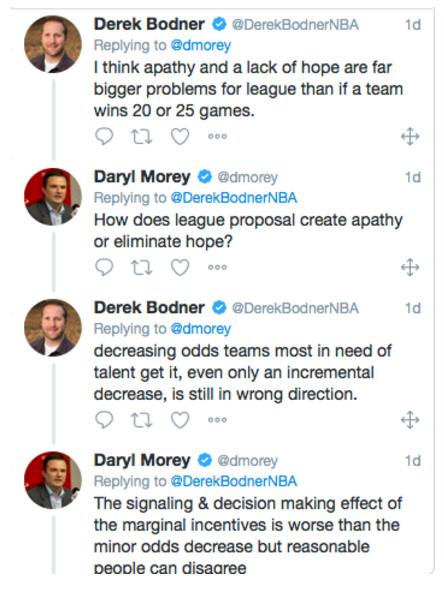

Longtime Sixers writer Derek Bodner, now with The Athletic, and Rockets general manager Daryl Morey recently had a lengthy Twitter debate/discussion about that very thing. They are both exceedingly bright humans, and they used many words, and I fully understood at least 62 percent of the conversation. (Absorbing the full transcript will qualify you as a speaker for next year’s Sloan Sports Analytics Conference.) For our purposes, here’s the germane portion of the exchange:

There’s a segment of the NBA brain trust, as a dusting of Morey’s argument suggests, that seems concerned not just with the effect of tanking on competition but also with the broader message it sends. It’s generally considered bad optics when fans embrace tanking on social media or the MSM feasts on the ensuing conversation. But why? The NBA, as Falk noted, is already divided. Eliminating tanking won’t eliminate the parity issue between the league’s best and worst teams, but it might make following and talking about bad teams in the offseason less compelling to certain fans. That would be a shame, because Offseason Bizarro Tank NBA has become a delightful and unique universe all its own.

What Bodner touched on, and what I think Morey, Silver, and other ranking members of the league hierarchy sometimes miss, is that fans of losing teams can lose interest. A good way to keep them engaged is to give them hope (or some semblance of it), and a good way to do that is to acquire high picks that just might turn into real-life dribblers and dunkers and shooters one day. More importantly, hope and interest come complete with eyeballs to watch your offseason product(s) and mouths to gossip about it. There’s a reason Lakers fans flocked to Las Vegas this summer, and it wasn’t to hear LaVar Ball yammer. Beyond that, assets and trade possibilities are why the ESPN Trade Machine even exists. That kind of stuff acts as a magnet that attracts the knowing nerds at the core of the current NBA fanbase. It’s fantasy hoops turned reality basketball.

There has been quite a bit of fretting about that last part, and not just by actual members of the NBA. Some fans and media see tanking as distasteful, something that runs counter to the primary principles of sport: Try hard. Try to win. That kind of thing. Except no level of earnest effort is going to transform the Kings into contenders. They’re the Kings, after all. If they’re going to lose games—and they are going to lose games, lots of them—why not afford them the opportunity to lose in the service of a better tomorrow? As Falk pointed out during our conversation, that’s something the anti-tanking hardliners often fail to realize or concede. It’s not that tanking teams aren’t trying to win, he said; it’s that—at least in his experience—they want to win “so badly that they’re willing to endure losing.”

“It bothered me when people said we weren’t trying to win,” Falk said. “We were trying to win, just over a different timeline than other teams. San Antonio rests players for certain games because they don’t care about winning every single game; they want to win over the course of a year. We did the same thing. We tried to maximize our odds. We were just trying to do it over a decade and not over a single season.”

At present, the NBA is currently a tiered system. You have the Warriors and whichever team LeBron is on in one tier. You have the upper-echelon teams like the Celtics, Spurs, and Rockets in another tier. (And fine, go ahead and graduate one or all of those teams into the top tier if you like.) Then there’s the tier with the remaining playoff teams, then there’s the teams that were close to the playoffs but missed out. And then there’s everyone else. The Everyone Else Tier is a sad, lonely tier. Tanking can make it a little less sad and a lot less lonely.

Consider the pro-Process masses that metastasized into loveable lunatics over the last few years. Any worries that their enthusiasm would wane during the protracted rebuild were recently allayed, as were concerns that tanking would hurt the team’s bottom line and crater business; when season tickets went on sale for the 2017–18 campaign, the Sixers broke their team record in roughly the time it took Pelicans fans to realize tickets were even on sale. (Sorry, Micah.) Doubtful that would have happened if the Sixers still had Evan Turner, Spencer Hawes, and Thaddeus Young as centerpieces instead of scions-of-tanking Joel Embiid, Ben Simmons, and Markelle Fultz.

Besides, the real issue isn’t tanking as a concept, it’s the aptitude of those who might apply it. Bad owners and general managers are the true enemies here. The league is attacking tanking as a cover to keep the overmatched from hurting themselves or anyone in their immediate vicinity too badly. But that’s an artificial fix, and it’s a lot less fun than letting organizations succeed or fail spectacularly of their own volition. That’s the thing about tanking. If it works, as I suspect it has and will for the Sixers, great. If it doesn’t, if a team spins out and wrecks the company car, there’s an attendant amusement component for the rest of us who get to rubberneck the crash. Either way, tanking can be mesmerizing and all-consuming. It’s a hobby unto itself. In the end, tanking can be damn entertaining. And what is the NBA, what is any sport really, if not ultimately entertainment?