John Lex knew something was wrong. The red Toyota truck three cars ahead of him on Florida’s Turnpike was driving like he was out of his mind. Changing lanes abruptly with no signal, tailgating slower drivers. He was clearly in a hurry to get where he was going, perhaps to work, Lex surmised. The truck was overloaded with construction equipment. When it finally made contact with the shoulder rail after over-swerving into the right lane, that equipment went flying all over the interstate as the truck somersaulted into the field below the shoulder.

Lex pulled over and made his way to the truck, which sat in the gulley, turned completely upside down. The driver was still inside, hanging in by his seatbelt. His face was covered in glass from the shattered windows and blood from his cuts. A shard had dug into his forehead, and blood poured from it.

“Help me,” the driver wheezed. “I’m hurt.”

Lex worried that moving the driver too quickly before knowing what injuries he might have could risk more injury. But Lex also smelled gasoline and knew that there was a real danger of the vehicle catching fire and possibly exploding.

“Help me, I’m hurt,” the driver repeated. Lex futzed with the seat belt but couldn’t get it to unfasten, so he pulled out a pocketknife and sliced the straps, then dragged the driver out to a safe distance from the truck. A nurse who had arrived to assist approached him and asked what she could do.

“Take a look and see what injuries we’re dealing with,” Lex said. “I’ll go start moving that debris out of the road before anyone else hits it.”

“Wait,” the nurse called to Lex. “Who are you? Are you an EMT?”

“No, ma’am,” Lex replied. “I’m a trucker.”

John Lex isn’t just any trucker. He’s perhaps the most famous trucker in America today. It was Lex who was sitting next to Donald Trump in that now-infamous photo op of the president honking the horn of a Mack truck on the White House lawn in March.

John Lex isn’t just any trucker. He’s perhaps the most famous trucker in America today. It was Lex who was sitting next to Donald Trump in that now-infamous photo op of the president honking the horn of a Mack truck on the White House lawn in March.

Lex and I roll down I-75 in that very same truck, a 2015 American-made Mack Pinnacle sleeper with a 550-horsepower engine. A gold bulldog is affixed to the hood, indicating that it’s fully Mack from end to end. It comes with an air-ride system — air bags that attach the cab to the frame — so it’s easy to forget we are in a massive piece of heavy equipment that could demolish anything in its path.

“This right here could make for a bad day for a lot of people,” Lex says, dead serious. In his camo cargo shorts and bright-orange T-shirt, he looks every bit the part of a truck driver. He’s 6-foot-2, and sporting a salt-and-pepper goatee. He hides his eyes behind wraparound shades. But he has a boyish grin and an upbeat affect that betrays the trucker stereotype. As he describes the power this truck possesses to rain down havoc and mayhem, he does so with the demeanor of a grade-school teacher.

I look out the window and see the 28-foot trailer behind us and it hits me: This machine is a harbinger of doom. Cars zip by us, ride right underneath our windows in the shade of the trailer, dip in and around as if we are just part of the scenery. Lex hugs the white line on the right side of the interstate with his right tire.

“I just stay on that line,” he tells me, “so that everyone has a good buffer of space on my left side.” His eyes dart from side to side, and his head whips back and forth as he casually makes conversation. Lex takes driving seriously. He sees his role behind the wheel no different from an airline pilot.

“I’m the captain of this ship. I’m responsible for all of this,” he says. “But that’s what I love about driving this truck. For me, that’s the pinnacle of any job. Captain of your own ship.”

Lex is more than just a truck driver. He is spreading the gospel of truck driving wherever he goes. In the truck, at truck stops, on the CB radio. He’s a member of America’s Road Team, a group of truckers from around the country who act as ambassadors for the industry. They attend civic events, speak at high schools, go to county fairs, all to make sure the public knows that nearly every good they consume is moved around America by a truck. That one out of every 15 people working in the United States — over 8 million people — work in the trucking industry. And that truck drivers are the best drivers in the country. The truck we are rolling in is on just such a mission. It isn’t filled with freight. In fact it’s nearly dead-heading, which means it is mostly empty save for our luggage and some supplies for the National Truck Driving Championships in Orlando, Florida.

About that: The National Truck Driving Championships is held each year by the American Trucking Associations to recognize the best drivers in nine different classes of trucks: step vans, straight trucks, three axles, four axles, five axles, twin trailers, flatbeds, tankers, and sleepers. Drivers qualify for the competition by winning a title in their home state, and competitions are held in all 50 states. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the NTDC. And the competition has remained largely unchanged since it began as the National Truck Roadeo in 1937.

When Harold Ickes was secretary of the interior in 1939, he famously complained about truck drivers taking up space on America’s highways. “The lord of the highway is the truck driver,” Ickes said. “I have promised someday to give myself the pleasure of driving down a truck-infested road in the biggest armored tank I can find and bumping these pests from the road.” Ickes advocated that the federal government bar trucks from the roads on weekends and holidays. The National Truck Roadeo was an attempt by the ATA to combat this image of trucks as an unsafe nuisance, and to promote the truck driver as a skilled professional possessing rare and useful talents.

Perhaps your perception of the American truck driver is informed by films like Smokey and the Bandit. You may assume, as I did, that the National Truck Driving Grand Champion is someone who can haul ass, driving a truckload of Coors beer across the Mississippi River before it turns warm. You’d be wrong. Anybody can get in a truck and step on the gas. Where a trucker’s true skill lies is in how he uses the rest of the truck: the brakes, the mirrors, the wheel, the angles. A great truck driver can breezily move a 50-foot-long vehicle carrying 80,000 pounds of freight into a tight spot with almost zero visibility. In fact, she could almost do it blindfolded. And to do that she has to drive slow. Very slow. It’s all angles and distances. Like golf. But much, much louder.

Most importantly, however, a great trucker is a superior driver to everyone else on the road around them. That means the test of a great trucker isn’t how fast he got the freight to and fro, but rather how many millions — yes, millions — of miles he can drive without an accident. It’s for this reason that to even be eligible to compete, a trucker has to go a whole year without receiving a ticket or being involved in an accident of any kind.

Though technology and trucks have changed dramatically over the past 80 years, the structure of the NTDC competition has remained largely the same: Drivers take a written test, conduct a staged inspection of a truck looking for planted defects, and take a trip around an obstacle course featuring six “problems.” This year the whole thing takes place inside the Orange County Convention Center, which is somehow massive enough to fit a few dozen big rigs, a grandstand, and enough room for two different driving courses.

It’s like the Olympics, only instead of countries, drivers represent their employers, and the employers foot the bill. This year’s contest has more than 420 state champions from all 50 states representing more than a dozen different companies large and small, including Old Dominion, XPO Logistics, UPS, and Walmart.

By far the largest company represented at the 2017 NTDC is FedEx, with 173 competitors. The drivers and their families all wear purple shirts, wave purple foam fingers, shake FedEx noisemakers, and rent out an entire wing of the convention center to hold private functions. This is FedEx’s second year bringing such a large contingent to the national championships. Last year the company broke a record with 174 drivers, overwhelming the grandstands and the convention center. Their presence grated on some of the drivers from other companies. Stories abound of drivers entering divisions with trucks they had never driven before, like step vans, just so they could try to put the squelch on FedEx’s domination of the competition. UPS, FedEx’s major rival in the marketplace, tries to whip their end of the stands into cheers to drown out the FedEx fans. It’s no use. After a few sad attempts, the UPS fans won’t even stand up as their cheerleader hollers a half-hearted “Give me a U!” FedEx has broken their spirits. One upside, however, is that every other company is now unified. More than once I hear people say the words, “Anybody but FedEx,” in the corridors of the Convention Center.

It hasn’t always been this way. In 1996, Roland Bolduc had been driving for FedEx for three years, though he had been behind the wheel of a truck his entire life. The son of a truck driver who ran his own trucking company, Bolduc had never known any other professional life than driving trucks. Bolduc caught wind of the National Truck Roadeo from a manager he worked with at FedEx in Windsor Locks, Connecticut. He fancied himself a damn good driver. Working for his dad, he had driven everything with wheels, from a forklift to a straight truck to a tractor-trailer. He had a knack for maneuvering in tough spots. Before he worked for FedEx, he drove for Magnolia Foods in and out of Harlem and the Bronx every day. His father would cajole him as a kid learning to drive: “If you can’t put it in there you let me know,” he’d say, cigar chomped between his teeth and a smart-ass grin on his face, “and I’ll put it in there for you.” Bolduc never needed to let his old man take the wheel.

The first year Bolduc competed in the Connecticut state championships, he was the only FedEx driver in the contest. He finished ninth out of 10 drivers in his division. The loss smarted. He could have said, Forget it, I don’t need the ATA to tell me I’m a good driver. But his competitive edge took hold. He went to his boss at FedEx and said, “I know what I need to do to win this thing next year.” Bolduc bought lumber, paint, and tape and constructed his own obstacle course on a FedEx lot. He’d stay after hours and on weekends to practice. The other drivers at FedEx thought he was nuts. But when he returned in 1997, he won the state championship.

At nationals in Minneapolis that year, there was only one other FedEx driver, a woman named Karen Tierney from Rhode Island. Bolduc and Tierney marveled at the number of drivers from other companies, their matching uniforms, the team atmosphere they’d built. Bolduc knew he had to figure out how to get FedEx to participate in this competition in more states, so that when he came back the next year he’d have a team to cheer for and to cheer for him. He teamed up with Becky Betts in corporate communications. She interviewed Bolduc about his experience and sent the audio tape out to all of the company’s drivers around the country to listen to in their trucks. In a few years there were FedEx drivers from all over the country competing. By 2003, a FedEx driver named Mark Dietsche from Oregon was named Grand Champion, the top honor at the NTDC.

FedEx had spent the ’90s and early 2000s acquiring regional trucking companies to expand the company’s reach. This brought a number of experienced drivers into their ranks, many of whom had been driving their entire lives — some were even veterans of the National Truck Driving Championships.

One of those drivers was a lean and dapper country boy named Wayne Crowder. Crowder grew up on a Kentucky farm and knew that in his neck of the woods there was only one way to get out and see the rest of the world. “You got to get in a truck,” he tells me. So he partnered up with his ex-father-in-law in the early ’80s, bought a truck, and hired it out.

Crowder got out of the Kentucky loam and bluegrass sure enough. He drove across 48 states, picking up loads and dropping them off wherever they needed to go, then back out on the road in search of the next load. He was an owner-operator “over the road” long-haul driver, the toughest truck driving job there was. He lived out on the road for as long as six weeks at a time, sleeping in his truck at truck stops and parking lots and rest areas across America. But he slept as little as possible. “If the wheels ain’t turning you’re not making money,” he says. So he stayed on the road, away from his wife and kid, burning up gas he paid for while he dead-headed from drop-off to pick-up, waiting hours for loads to arrive, sitting idly, making no money and wondering what in the hell he was doing out on the road trying to eke out a living this way. “But there’s just nobody looking over your shoulder,” Crowder says with a grin, “and there’s just something about it that is kinda free.”

Eventually, in 1994, he heard about an opening at a new company, American Freightways, where the pay was good and the hours and routes would keep him home every night. He line-hauled from Louisville to Knoxville and then passed his trailer on to another truck to take it the rest of the way. It was a form of just-in-time distribution, and it was changing the way trucking companies operated. Crowder was relieved to finally sleep in his own bed while not having to give up his freedom.

By 2004, American Freightways had become part of FedEx, and Crowder had heard all about Mark Dietsche’s national championship. Crowder had heard of the Truck Roadeo when he was a kid, hanging around the tobacco houses in town listening to truckers talk about it. Crowder figured he was a pretty good driver his damn self. So he entered the competition the year after Dietsche won. He won the Kentucky state championship in his first shot. At nationals, he set a goal for himself of making the top 25. After he missed 12 of the 40 questions on the written test, he figured he’d miss hitting that goal. But he nailed the driving course and won Rookie of the Year and Grand Champion in the same year, the only driver to ever win Grand Champion his first year out. Some folks thought it might be a fluke, that a driver couldn’t possibly win everything having never driven competitively before. But the next year he won the state championship again and was runner-up for the Grand Champion at nationals. The fluke talk stopped after that. Folks took notice, both of Wayne Crowder and FedEx. Whatever misconceptions truckers may have had about FedEx before that year, they now all saw FedEx as a real-deal trucking company, with real-deal truckers like Wayne Crowder behind the wheel.

The first day of the 2017 National Truck Driving Championships appears to be fairly uneventful: More than 400 truck drivers sitting in chairs quietly taking a standardized test. The written portion of the test has remained a key part of the championships since the very first competition in 1937, but the material the drivers are tested on has expanded dramatically over the past 80 years.

To prepare for the exam, drivers obtain a copy of the annually updated Facts for Drivers. The 199-page tome includes information on driving rules and regulations, truck mechanics, emergency first aid, and even fire fighting.

Most drivers get Facts for Drivers on CD and listen to it while they drive — hours and hours of questions and answers being read aloud. “It’s like taking an ice pick to the head sometimes,” Crowder says. And the written portion of the competition scares away drivers who believe themselves to be skilled behind the wheel but bad at test-taking. The drivers who study it swear it has turned them into truck-driving Navy SEALs. It instructs drivers on how to treat open wounds, rip up their mattresses in their sleepers to soak up spilled fuel in an accident, and even use a bar of soap to plug a leak like MacGyver. It was Facts for Drivers that taught John Lex how and when to remove an injured person from an overturned vehicle. Facts for Drivers saves lives.

“Wake up, Bo.”

Al Lex woke up his 6-year-old son at four o’clock one morning in 1982 to come with him to work. It seems cruel, but young John, whom his father affectionately called Bo, wouldn’t have had it any other way. He leaped out of bed. He watched his father, a driver for the grocery chain Publix, polish his boots and button up his uniform. John loved the way his father looked in that uniform. He loved the way the waitresses at the all-night diner treated his father with respect, same as if he were a police officer or an airline pilot. There was something about a uniform that made someone special, John figured. Important, even.

John followed in his father’s footsteps, first working in a warehouse at Publix, and then behind the wheel just as soon as he could get his chauffeur’s license at 18.

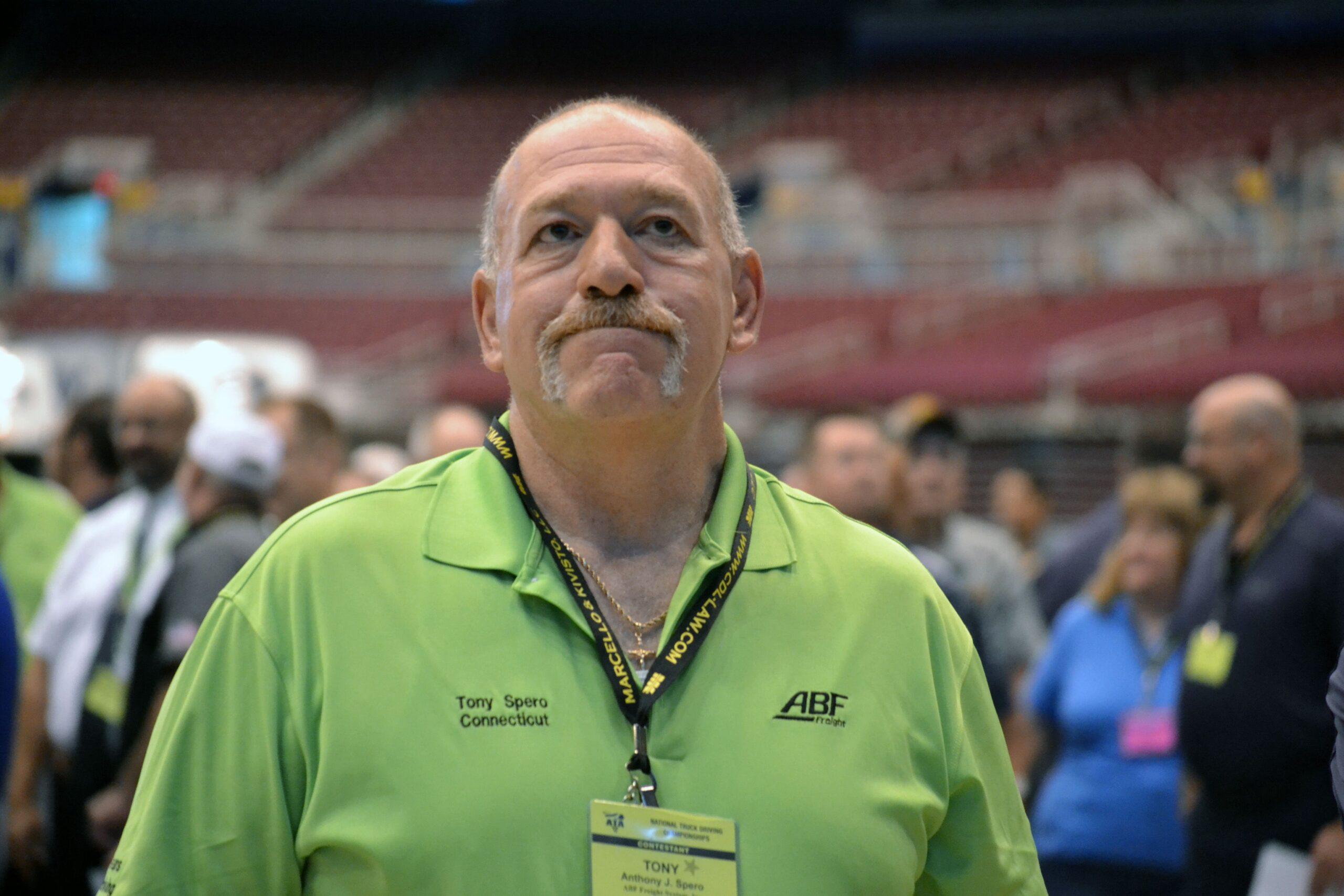

This is a common story among truck drivers. Like Lex and Bolduc, many drivers at the NTDC are second- and even third-generation truck drivers. Tony Spero, a stout 56-year-old trucker for ABF from Connecticut, is one of the drivers that Roland Bolduc practices with throughout the year to get ready for the NTDC. Spero started driving the year his own father retired after nearly 50 years behind the wheel. Today, Spero’s two sons are also truck drivers. At first Spero tried to discourage his sons from going into trucking.

“Aren’t you going to go to college?” Spero asked his oldest when he announced his intention to get his commercial driver’s license after graduation. “You’re a working man,” his son told him, “and look at you. You’ve done well. Ain’t nothing wrong with being a working man.”

Spero figured that was right, and he’s proud of his sons for carrying on the tradition. But he’s quick to point out that not every driver coming up today has the same experience. The industry has changed a lot since his father was driving. But while his sons work for different companies than he or his father did, they’ve all been members of the Teamsters.

“I work under a good union contract for a good company that takes care of their drivers,” Spero says. “And now my boys are Teamster truck drivers. The trucking industry’s been good to my family.”

Lex and his father were driving in South Florida, where the Teamsters weren’t as strong as in the Northeast. Nevertheless their jobs at Publix were decent enough. Still, like Wayne Crowder, the open road called Lex’s name. “It sounds crazy,” Lex says, “but I really wanted to sleep in a truck. To me that was the real deal.” He wanted to be an over-the-road driver.

But those jobs, while in large supply, weren’t quite what they used to be. That’s largely because of the deregulation of the trucking industry in 1980. Steve Viscelli, an economic and political sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of The Big Rig: Trucking and the Decline of the American Dream, says that before deregulation, from about 1950 to the 1970s, “truckers were the best-paid and most powerful segment of the U.S. working class.” Those regulations were a result of the Motor Carrier Act of 1935, which put trucking under the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), the body that decided which companies could haul which freight.

The hope was that regulation would prevent monopolies. But Jimmy Hoffa and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters figured out how to leverage regulation to the benefit of drivers and companies alike. Hoffa brought drivers together across companies into a single master union contract, standardized wages so that companies wouldn’t compete over who could pay the least, worked to bring up rates paid to employers, and shut down smaller companies that tried to undercut the standards they had set with strikes and picket lines. For much of the period of regulation, Hoffa single-handedly controlled the trucking industry in America, and he used that power to turn what was once a dangerous and low-wage job into a path to the middle class for millions of American truckers.

It wasn’t to last. In 1967, at the height of his power, Hoffa went to prison for jury tampering and mail fraud. His successor, Frank Fitzsimmons, made a mess of the master contract and the tight coordination between the employers and the multitude of Teamster locals throughout the country. To avoid dealing with the Teamsters, by the late 1970s, many customers of big trucking companies started building their own in-house trucking fleets to move their products and goods. Meanwhile, the pressure to deregulate the trucking industry began, from think tanks like the Brookings Institute and the left-wing consumer advocate Ralph Nader.

The hope was that deregulation would lower consumer costs of retail goods, since the increases in rates paid to shippers was being passed to consumers. The downside was that the cost of that decline was borne almost entirely by American truck drivers. According to Viscelli, in the first five years of deregulation, 6,740 carriers went out of business, including over half of the major general freight carriers. By the end of the 1980s, over-the-road truck drivers’ wages and benefits had been cut nearly in half.

Under the master union contract, the over-the-road long-haul truck driver, who worked the longest hours driving the longest distances and stayed away from home for weeks at a time, was the highest paid; most drivers preferred local routes, propping up wages for the OTC jobs. But after deregulation, it was the over-the-road long-haul jobs that exploded in growth. Many of these were union companies. By 1991 only five of the top 50 trucking companies from 1965 remained in business. Meanwhile, literally hundreds of thousands of new companies appeared, the vast majority of them operating fewer than 20 trucks. They specialized in the general freight over-the-road segment of the business, called truckload, and the competition among these new firms was intense. Without a union to standardize and enforce pay, these companies competed for business over who could pay drivers the least. Thousands of new truckers entered the industry in a dangerous job that was now the lowest paid, with most drivers staying on long enough only to pay off debts from obtaining their commercial driver’s license and getting enough time behind the wheel to make the jump into a better job, like with a retailer’s own private fleet.

It didn’t take John Lex long to figure this out. He soon grew tired of sleeping in his truck. “I’m 6-foot-2, and trying to undress in the cab ain’t comfortable.” He started noticing several drivers at truck stops in Walmart trucks. Walmart was growing at a rapid clip, and it was dramatically changing the American economy — particularly by running its own fleet of trucks and benefiting from their stores’ seemingly boundless inventory. Their drivers rarely, if ever, ran empty. But what really caught Lex’s eye was that Walmart drivers wore crisp, white dress shirts and ties, with an American flag patch on the sleeve. They looked like airline pilots. They reminded him of those old days when his father would turn heads in the diner. Lex would get on channel 19, the main channel on the CB for truckers, and ask Walmart drivers to get on a lower channel so they could speak privately. “Hey,” he’d ask once they got on a lower channel. “Do you like your job?”

Walmart offered Lex a job, but he’d need to relocate his family from South Florida to rural Georgia. He didn’t hesitate. What he got in return was a schedule that kept him home more often, a salary that paid him not just for the miles he drove but for the time he spent waiting or even sleeping in his truck, and one of those fancy white uniforms.

Walmart quickly developed a reputation in the trucking industry as the gold standard. According to Viscelli, Walmart was paying its drivers double what most over-the-road drivers were making. “A Walmart driver can start at $80,000, and definitely get close to $100,000 with work hours that are much better,” Viscelli told me. Not only was the pay better, but the work wasn’t nearly as grueling.

Walmart had built a logistics network that was as efficient as anything that had come before it. Their drivers had little uncertainty, and almost no down time. It was like a 9-to-5, a sea change for many truckers. The efficiency eliminated much of the stress that drivers were used to, which meant they were happier and safer. They didn’t need to speed to make more money, or to lie or cheat on their log books like many did in the early days of deregulation. They could be home with their families more often and make enough money for a comfortable life. As a result, Walmart attracted many of the best and most experienced truckers in the country.

Working for Walmart also meant that it would be harder for Lex to compete in the National Truck Driving Championships. That’s because Walmart lets its drivers compete at state championships only if they first qualify in a companywide contest. Fewer Walmart drivers show up at nationals each year, but Walmart figures it’s sending the best. The results back up the company’s strategy. Entering the 2017 NTDC, Walmart had won three of the past four Grand Championships — even last year, when more than a third of the field was made up of FedEx drivers.

Roland Bolduc gears up for his pre-trip inspection in the bullpen where he and four other drivers wait for their turn to enter the arena. This is his 14th trip to nationals since his first in 1997. For good luck he’s worn the same uniform every time he’s competed. It still fits today, though a bit more snugly. He’s made some adjustments over the years. He attaches a flashlight to one wrist, and a more powerful flashlight to his leg by a velcro strap. He wears a headlamp on his forehead. He carries a knocker for the tires. And he straps a timer on his left biceps that’s programmed to alert him where he needs to be at each interval of inspecting the nearly 80-foot-long sleeper truck and trailer.

When he’s given the go-ahead to begin, Bolduc moves around his truck like a man possessed. He looks under it, around it, climbs inside of it, head always moving and searching for anything out of place, anything out of the ordinary. He slides around it in a well-rehearsed pattern, calling out defects and mistakes as he finds them. A crack in a window, an expired sticker, something loose beneath the pedals. Each time his timer goes off he knows he’s at the right point on the truck. He’s in his zone. As he reaches the one-minute-remaining mark, he looks at the judge and says, “I think you need to give me the one-minute warning.” Surprised, the judge looks at his own timer. “Oh, you’re right. One minute remaining.” Bolduc grins. There are no nerves, no butterflies. The truck is the thing he does better than anything else. The truck is where he’s at his best. The truck is home.

At the same time Bolduc does his pre-trip inspection, Tony Spero readies himself to drive the main course. Like Bolduc, Spero is no stranger to the NTDC. This is his 16th competition. He says he holds the record for the most state championships in Connecticut. He also holds five pre-trip inspection awards, and has won two national championships, in 2006 and 2009. Still, he seems nervous as he prepares to enter the truck to drive the course. “I feel good,” he says, “but sometimes when I feel good I end up not doing so good, so I don’t know.”

Spero climbs into the tanker and pulls the levers on the dash to activate the air brakes. The truck lets out a series of high-pitched hisses of air. He slowly rolls the tanker forward and applies the brakes to see what kind of give they have, what all he has to work with today. He then accelerates into the course. The timer begins.

He weaves the truck in and out of the serpentine pylons on the first obstacle, then pulls the truck forward to set up for the next problem, a left tire stop. He has to put his left tire directly onto a square, judging the distance without being able to see it. Some drivers use shadows or marks on the ground. Tony knows how to time it from practice, counting once the square vanishes beneath his hood.

From there, Tony moves on to the mother of all obstacles — the parallel park. He has to put the tanker between two barricades without touching either one and still get as close to the line as he can without going over. The barricades are the exact distance of the length of the trailer plus 4 feet, so there’s very little room for error. When executed perfectly, the truck is in an L shape, the tanker in the spot and the cab sticking out at a right angle. The highlight of the course, the parallel park is right in front of the grandstand, where the crowd can cheer the drivers on.

As Tony slides his tanker into the space, the ABF section of the crowd stands in tense silence, hands over their mouths. When Tony honks his horn to indicate to the judges he’s ready for them to measure, he feels good about how close he is. Tony has a parallel obstacle set up on the ABF lot back home. He practices on it almost every weekend. Sure enough, the tanker sits perfectly between the barricades. The judge waves a green flag. The crowd exhales with a cheer.

After carefully pulling the tanker out from between the barricades, Tony speeds up a little to set up for the next obstacle, a left-turn double roadkill. They call these problems roadkill because the driver has to get their tires as close to two offset yellow rubber duckies as they can without touching either of them. The rubber ducky is the NTDC’s unofficial mascot, and these two are black and beaten from all the abuse they’ve taken today from big rigs rolling over them. Tony wastes no time in swinging by them, sparing their lives and getting close enough for a perfect score.

Then Tony brings the tanker around for a side stop, where he must line up the right side of his truck as close to a line on the ground as he can get without touching it. Then it’s on to the final obstacle, a front stop with a passenger-tire qualifier. He has to stop the truck with his bumper perfectly aligned with a marked area on the ground, while also lining his left tire up into a very narrow box without touching any of the lines. He navigates his left tire perfectly into the qualifier, but slams the brakes a little too hard and stops short of the line.

Though drivers aren’t supposed to know their scores, when Tony gets out of the truck he can see that he missed his mark, and he looks crushed. He climbs onto a golf cart that waits to whisk him away, back to be sequestered with the other competitors in a bullpen. “I feel nervous,” Tony later says. “I could have done better. Maybe some of the other guys could have done better, too. You just don’t know.”

The awards banquet that night was attended by more than 1,000 people, truckers and their families, dressed to the nines. There were sharp suits, a few cowboy hats and bolos, high heels and elegant dresses with tattoos peeking out from beneath the straps. Tony arrives with his wife, Dee Dee. He sports a white shirt and a green tie, matching ABF’s company colors. Dee Dee carries a white rose. In the end, Tony is one of the five finalists in the tanker division. All of the top five from each division are to be honored on stage with their spouses. Despite Tony’s many trips to that stage, tonight will be the first time Dee Dee will make the walk with him, and she’s nervous. “I don’t want to walk,” she says. “I don’t usually dress up like this.”

When Tony’s and Dee Dee’s names are called, he takes the stage with the other finalists from each division, including Wayne Crowder and Roland Bolduc. As they come down from the stage, cheering drivers high-five them and hug Dee Dee. “No matter what happens,” Tony tells me, “this was better than winning Grand Champion. To see all of these drivers, some of whom I’ve never even met, giving my wife hugs and cheering for her, that means everything to me.” He puts his arm around Dee Dee. “That’s why I love doing this. The bond. The bond between drivers.”

After speeches are delivered by various dignitaries, the moment arrives to crown a Grand Champion. Five hundred truckers sit in silence. Some in the FedEx section even stand on their chairs in anticipation, so sure they are that this is their year. They finally call out the name Roland Bolduc. The FedEx faithful lose their minds. The ballroom erupts. It takes him what seems like five full minutes to make his way through the crowd to take the stage. Every driver, FedEx or otherwise, embraces him. The love is real.

It would have been this way no matter who won, but it feels especially real in this case, because truck drivers know that Bolduc lives for this. From the days of building his own barricades to helping spread the competition throughout FedEx and New England, assisting other drivers as they prepared for the competition, helping run state tournaments, recruiting new drivers to compete, Bolduc has been at the center of it all; these drivers know this matters as much to Bolduc as it does to them, if not more. He is greeted with a standing ovation.

“I just kept hearing my father’s voice in my head,” Bolduc says. “‘If you can’t put it in there, I can.’” Bolduc’s father died in 2005, leaving the family trucking business to Bolduc’s siblings. “All these years later, and that stayed with me.” After 21 years of competitive truck driving, Bolduc had finally put the truck in there. He put it in there perfect and plumb.

John Lex and I are sitting in the cab of the Mack Pinnacle parked at a truckstop somewhere along the interstate on the way back from Orlando. We’re watching two guys try to back their truck into a parking spot. The driver is clearly new at this, and the man outside helping him is his company trainer. Things aren’t going well, and traffic is piling up. The voices on the CB radio are getting salty. “Only in fucking Georgia,” one driver snarls over the CB.

The for-hire over-the-road truckload segment of the industry — like the company this newbie works for — make up the vast majority of the trucks on America’s roads today. According to Steve Viscelli, the drivers earn little over minimum wage while working 80 hours a week, and turnover is incredibly high.

Viscelli argues that poorly paid, inexperienced drivers are more detrimental to safety than anything else. Government regulations can’t eliminate turnover, only better pay and working conditions can. And while changes in technology and the economy are creating better jobs, Viscelli worries that the lack of a strong union presence will limit their upside. “They’ll only be good jobs if workers have a voice in that.”

“The fact that you have thousands of lives lost in the industry every year,” Viscelli says about the NTDC, “and that truck drivers are the no. 1 occupation for on-the-job deaths. Unfortunately, a lot of it is out of your control. Most trucking accidents are not the trucker’s fault … and in 99 percent of the occasions, these truck drivers are much better drivers; they are trained to be better drivers.”

When Harold Ickes called the trucker the “lord of the highway,” he meant it as a dig. Like the name “Teamster” implies, truckers have been around since the days of horse-drawn wagons. For all but a moment, they have been overworked and underpaid. The ones who have made a life for themselves behind the wheel, like the drivers at the NTDC, perform a crucial role in our economic order and do so with an undervalued skill. They receive far too little in the way of recognition or reward. Paradoxically, the better a driver is behind the wheel, the less anyone notices them on the road. It isn’t until there’s an accident, or a truck gets stuck in a tight spot, gumming up traffic, that we notice them at all.

Lex chuckles as he watches the rookie driver try to straighten out his trailer, the grousing on the CB getting louder. “You know, when I was a kid, my mother used to call truck drivers the ‘Knights of the Road,’” Lex says. “They’d let you know when there was bad weather up ahead, or an accident. They’d pull over and help people in trouble on the side of the road.”

Lex gets out of the truck almost in mid-thought and goes out to help the struggling driver and his trainer. Once the truck is safely tucked into its spot he gives a fist bump to the trainer and climbs back in our cab. “First month on the job,” he says. “That’s what we’re dealing with out there.”

Lex pulls his truck out of the truckstop and gets us back on the highway toward Atlanta. Lex tells me about his father, who is still alive and attended the NTDC is Orlando. He recounts the time he parked this Mack truck on the White House lawn, how he got to tell the president of the United States how important truck drivers are to the economy, and to the roadways.

“Do you think he heard you?” I ask Lex.

“I don’t know. I hope so,” Lex answers. “I’m not really political. I’m an independent. I went to Washington, D.C., because ATA asked me to drive the truck. That’s what I do, I drive trucks. I didn’t even know what it was for until I got there!”

But later, as Lex stood in the D.C. airport preparing to fly back home after the dizzying experience of sitting just steps from the Oval Office, holding court with the president of the United States, he knew he had to call his dad and tell him what had just happened.

“I started bawling right there in the airport. I didn’t even care who saw me,” he said. “I told him, ‘Dad, I owe everything I have to you. You inspired me to do this. I still remember you shining those boots.’ And he just said, ‘I’m proud of you, Bo.’”

As he tells me this, the tears stream down from behind his wraparound shades. He seems a little embarrassed. “I’m getting emotional, but I mean, can you imagine? I’m just a redneck from Georgia. I would have never imagined the places this truck would take me.”

A car swerves in front of us, activating the truck’s cruise control braking system. Lex seems annoyed. He shakes his head from side to side. I wonder, were I not there riding shotgun, what expletives he might have uttered at that moment.

As the car settles in ahead of us, a tiny arm emerges from the rear window, pumping its little fist up and down. John Lex wipes the tears from his cheek. He dutifully pulls the cord and sounds the horn.