On the afternoon that Donald Trump threatened North Korea with “fire and fury” and the world busied itself with imagining what exactly a 21st-century nuclear war would entail, a man in Bridgewater, New Jersey, sidled up to the bar at Maggiano’s and ordered a glass of red wine.

The restaurant is hard to miss. It shines like a jewel alongside Bridgewater’s marquee attraction: a triple-decker mall that will set you up with everything from Uniqlo to Hot Topic to really good—seriously—empanadas in the food court. A quarter or so past 5 p.m. on each and every weekday, the bar at Maggiano’s starts to fill up, thanks largely to out-of-town pharmaceutical employees who stream from two towers down the road to the Marriott on the corner and, from there, directly on to the Maggiano’s bar. In the winter they shuffle across the street in parka-clad packs, like penguins. But Leroy was there early, to beat the rush and maybe make a dent in the gift certificate his son gave him.

He was a union man, he said, by way of explaining that his interest in Trump began and ended with concern over the 30-mile flight restriction imposed for the duration of the president’s stay at Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster, maybe a 15-minute drive away. A few minutes after a motorcade passed by carrying Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price and Trump counselor Kellyanne Conway to a press briefing at the Marriott—no sirens or anything, just a couple of discreet blue and red lights on the dashboards of a line of dark SUVs—Leroy ordered the spaghetti and meatballs. “Kellyanne?” he asked, his eyes growing wide. “She’s over here?”

The next day, press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders, suffering from a bad cold, would stand in the Marriott lobby and tell reporters that no, Trump’s aggressive statement on North Korea was very much part of the administration’s strategic plan. Then she would quietly get into a van and leave for Bedminster, passing the Maggiano’s on her way out.

Someday, there will be Donald Trump history tours. Tour buses will pull up alongside Notable Trump Sites, and out will spill vacationing empty-nesters and tweens on eighth-grade field trips and Ph.D.s in search of undigitized artifacts. There will be pilgrimages by devotees born long after the 45th president’s time in office wraps up, and they’ll leap out of beat-up Ford Fusions or Chevy Hovercraft 300s in vintage Make America Great Again caps.

To guide these future, Trump-as-quirky-pitstop people, there will be commemorative maps, maybe with gold stars to steer them from landmark A to B to C. There will be one for Trump’s childhood home in Queens, which has even now been rebranded the Trump Birth House by unknown buyers and listed on Airbnb for $600 a night. There will be another star for his sumptuous high-rise in Midtown Manhattan.

And then, 45 miles to the west of New York City, there will be what in all likelihood will be the most visited, most school-bused, most walking-toured, and most, yes, holy, because it’s the one which figures to be his final resting place: Bedminster. If Trump is buried there—a significant possibility, given he’s repeatedly petitioned the county and state for permission to build a mausoleum on the grounds of his golf course and spoken at length of his desire to spend eternity in the rolling central Jersey hills—Bedminster and its neighboring hamlets will be Trumpland in perpetuity. Should that happen, for decades hence, maître d's who haven’t even been born yet will grow weary of directing lost tourists up the road—get back onto 287, hang a couple of lefts, and stop before you hit 78. Future members of the Bridgewater police department will post NO BUS IDLING signs; gift shops on nearby Somerville’s tony Main Street will sell Trump bobbleheads and toupeed plushies and goodies we haven’t quite imagined yet: Trump vs. McConnell boxing robots, miniature border walls, mushroom cloud Christmas ornaments. Bedminster and its environs, more so than any other place except West Palm Beach’s Mar-a-Lago, are likely to be twinned with Trump forevermore.

Which makes it a little bit weird that hardly anyone even knows he’s in town.

Trump is on vacation, the first extended one of his now seven-month-old presidency. Even now, a week into the announced 17-day sojourn, the administration insists that it is not a getaway at all: “This is not a vacation—meetings and calls!” Trump tweeted after arriving. But he has repeatedly been pictured out golfing and members of the traveling press pool have almost daily been told there will be no news, being dispatched instead to wander through the mall and sample empanadas. The president has stationed himself at a luxurious, 535-acre estate built for the exclusive purposes of strolling, swinging, sunning, and dining. That this comes from a man who spent much of Barack Obama’s presidency complaining about no. 44’s vacations—“Can you believe that, with all of the problems and difficulties facing the U.S., President Obama spent the day playing golf,” came one representative tweet in 2014—has inspired the predictable outcry.

However you measure these things, the Trump presidency has been loud. The pandemonium caused by Trump’s Tuesday threat toward North Korea was, in its own way, business as usual. Brash, bombastic comment from Trump that may or may not, despite Sanders’s later insistence, have been run by his advisers beforehand? Check. Days-long media frenzy in the aftermath? Check. Steady walking back by deputies after the fact? Check. You can argue, with varying degrees of risibility, that the chaos is intentional: Fox News host Jesse Watters said as much on Wednesday, when he argued on The Five that Trump “being unpredictable is a big asset, [because] North Korea knew exactly what President Obama was going to do.” (The president subsequently retweeted the quote.) But it is chaos nonetheless.

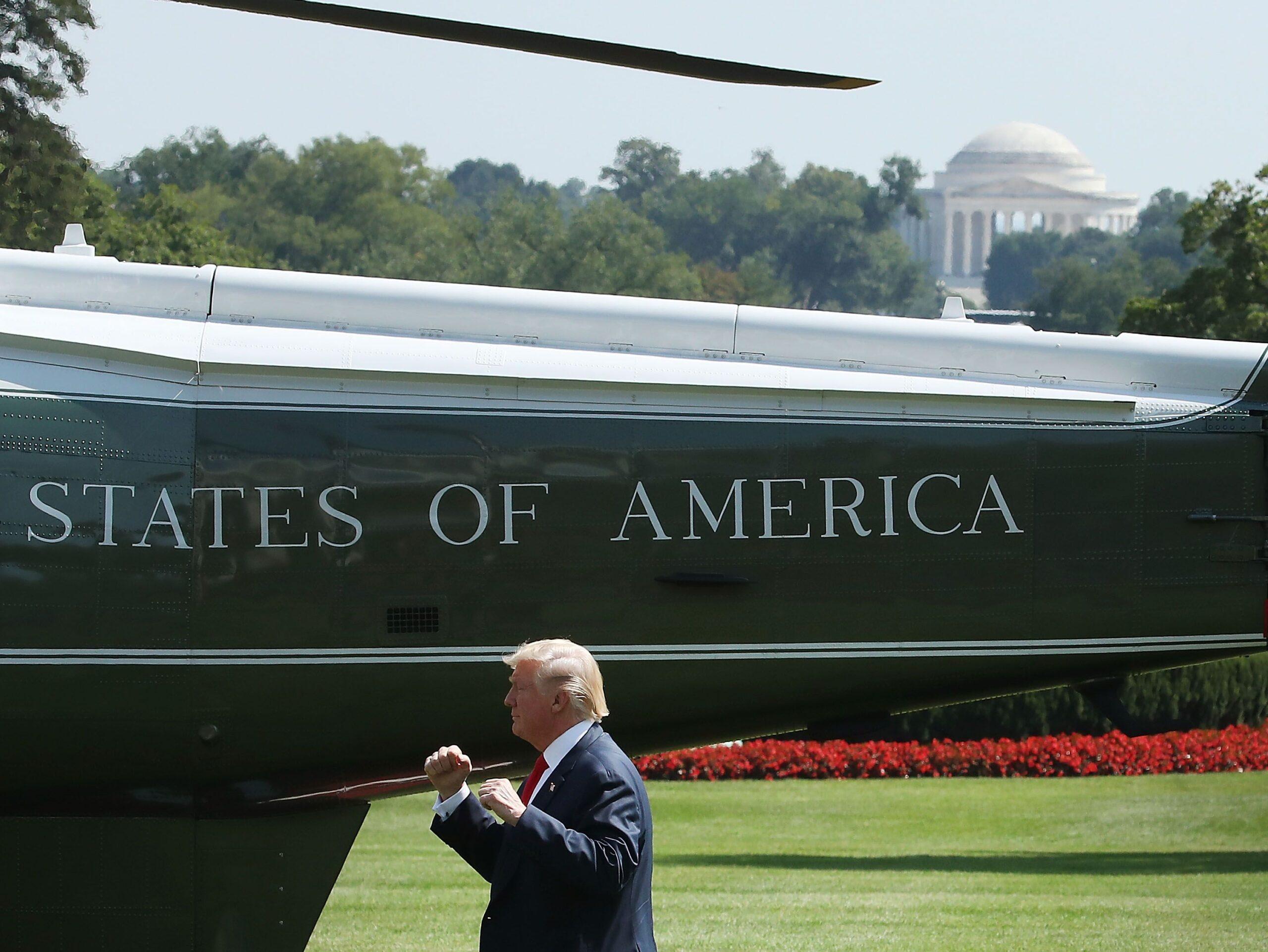

And yet, in Bedminster—which Trump won in November with a margin of eight votes—there is simply quiet. Few in the area seem to have any idea the president is there at all, and, when informed that he is, mostly respond with mild interest, like you told them your grandmother had just arrived for a visit. Trump is not, after all, exactly in town: When he’s in Bedminster, he is very specifically at the Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster. (The town of Bedminster itself is so small that staff and reporters are obliged to stay in the next town over instead; visiting television producers have repeatedly expressed anguish that, absent an accessible Bedminster sign, they’re forced to broadcast in front of a busy road in Bridgewater, an altogether less exotic dateline.) On Friday, August 4, the presidential helicopter, Marine One, lifted off from Morristown Municipal Airport, setting down at Trump National just before 6 p.m. Trump hasn’t emerged from the club since. He is not expected to until Sunday, when he returns to Manhattan for three nights at Trump Tower. After that, he will likely return to Bedminster for a final few days at the golf course.

His time in Bedminster is hardly out of character. While presidents usually like to use their dining as a form of folksy diplomacy—a dinky diner here, a regional delicacy there, a not-quite-candid picture with beaming restaurant staff over there—Trump has been a remarkable homebody. Apart from his three trips abroad, he has not once since taking office publicly dined in a property that he did not live in or own. In Washington, D.C., he has gone out for dinner only a handful of times, each and every one of them at his downtown hotel. He has taken day trips to his golf club in Virginia on 15 occasions, and spent seven weekends at the crown jewel of his club system, Mar-a-Lago, where he was similarly cloistered. After Mar-a-Lago closed for the summer months, Trump began vacationing to the north. His August vacation marks his fifth presidential visit to Bedminster—his sixth, if you count the weekend in July when a rally took him back to D.C. and then he opted to return to New Jersey that evening anyway. On each occasion, he has either helicoptered or motorcaded into the grounds and then remained there, safe from the view of everyone but his guests and club members, who for this honor pay $22,100 a year plus somewhere north of $75,000 as an initiation fee.

It makes for a starkly different scene than his predecessor. While president, Obama typically took two long vacations each year: one over Christmas to his native Hawaii, and one in August to Martha's Vineyard. In both locales, he and his family rented homes in exclusive neighborhoods alongside a cast of friends and senior White House staff. And in both locales, the Obamas were gadabouts during their stay, dining out at the same restaurants year after year. It became something of a parlor game for locals and fellow vacationers: Was this the night that the Obamas would show up at Alan Wong's? They haven't turned up at L’Étoile yet—would it be wise to make a reservation there in the hope of catching a glimpse? Obama tended to make a show of rotating through different golf courses—worth setting a tee time just in case?

In Martha's Vineyard, Obama’s motorcade snaked through the island's roads, a police escort leading the two dark vans containing the president and his fellow passengers. Sasha got a job at local seafood institution Nancy's. Still, it was hardly egalitarian: Even on ritzy Martha’s Vineyard, Obama tended toward the most exclusive destinations, and was always ensconced behind police barricades, slipping out of vans and directly into the back exits of restaurants, from which he and his family were escorted to private rooms. But he made a show of acknowledging the throngs of giddy onlookers, who gathered invariably at those barricades whenever and wherever they were erected. After finishing a meal, the odds were good that Obama would duck past his waiting ride to wave to the crowd, and perhaps walk down the street to the corner ice cream parlor. It was a way of scattering The Time I Saw Obama stories into the crowd, a shared sort of presidency.

But now we have New Jersey. We have the Buffalo Wild Wings on the side of 22, the Friendly’s, the strip mall with the shop specializing in XXXL clothing for men. We have those rolling green hills, the 4-H signs on highway overpasses. We have jug handles. We have the wraparound bar at McCormick’s where everyone is playing pool, and the BYOB arcade just off the very Main Street where Trumpian knickknacks might be sold 100 years from now, where on the right night you might find reporters and maybe some Trump aides playing Mario Kart, where the locals neither notice nor care. Where there’s a really great classic car show put on every summer Friday in Somerset with live music, the kind of silly local thing a different president in different times might pop by to shake some hands.

But the club is out of the way. It’s not on the way to anything; to get a glimpse of it, you have to go there directly, and if you go there directly, you’ll pull up to the lovely little stone booth by a sign proclaiming it the site of last month’s U.S. Women’s Open, and a nice young man in a lilac polo shirt will ask smilingly just what you think you, a non-member, are doing there. This is assuming you have been permitted to pass a pair of waiting Secret Service agents, who as a rule are not nice. Ask around, and you will learn that everyone seems to have heard it’s pretty nice at Trump National. (You will also learn that the all-you-can-eat lunch special at Sushi Palace is just $10 and really—really, no, seriously, don’t laugh, really—good. It is.)

The result of Trump’s approach to the presidency, both while vacationing and while more plausibly at work, is a profound sense of isolation. The darker imaginings have him alone for hours at a time, clad in a bathrobe—a detail heartily denied by the White House—and lying in bed as he watches cable news, phone in hand, tweeting as the inspiration arrives. As president, the world he has fashioned is almost breathtakingly small and is composed entirely of the familiar. And yet from this calm and stationary island, he not only manages to wreak havoc far and wide, but also seems to enjoy doing so. He is a sort of roving eye of the storm—one that is nearly always of his own making.

There are some rationales for the self-cosseting, of course. Trump entered office with razor-thin margins in many states, and lost the popular vote. His first moments in office were spent standing on the steps of the U.S. Capitol building and gazing out upon a visibly sparse inaugural crowd; his first full day was one in which much of the country erupted in protests against him. He has made decisions since then, notably not to tack to any sort of center, and he has been rewarded with dismal approval ratings. If he were to wander out for an ice cream cone, it’s very possible that he wouldn’t be met with cheering crowds. And indeed, he has pulled the plug on outings where such a thing might occur, telling British Prime Minister Theresa May that he would not visit the U.K. until she could guarantee him a welcoming audience. He has insisted that he’s stayed away from Manhattan’s Trump Tower to spare New Yorkers the traffic jam; come this weekend, we’ll see if the city’s response to his homecoming suggests a different reason.

Toward the end of his presidency, Obama spoke often of missing his anonymity, of the ability, surely, to wander into someplace like Maggiano’s, grab a stool beside the Leroys and the pharma execs, pick up a complimentary copy of the USA Today sports pages, and not be bothered. With Trump, it’s becoming clear he never wanted to be there at all.