Welcome to Inefficiency Week. Over the next five days, we’re going to take a look at what we lose when we get lost in the chase for efficiency. We’ll explore the ways it’s changing the games we love to watch. We’ll remember its failures across the pop culture spectrum. And we’ll report on what it’s doing to our lives — romantic, physical, and otherwise.

Few NBA players do more with less better than Chris Paul. Point guards are typically the smallest guys on the floor, and Paul (6-foot and 175 pounds) is undersized even for his position. He isn’t particularly fast, either — not after knee injuries robbed him of the elite speed he had his first few seasons. He doesn’t just get by on basketball IQ, toughness, and guile; he dominates. Paul is one of the most efficient basketball players in the history of the game. He’s second all time behind John Stockton in assist percentage, and he’s first in offensive rating. The only hole in his résumé is in the playoffs: In 12 seasons and nine trips to the postseason, his teams have never advanced past the second round. Even in defeat, Paul has posted great individual numbers, but he hasn’t been able to consistently win individual matchups against the league’s other great point guards. Efficiency can get you only so far in the postseason. Physical tools matter when you are going up against the best of the best.

There is no one better at taking advantage of inferior opponents than Paul. He maximizes every possession, and he doesn’t take plays off on either side of the ball. He rarely makes the wrong decision on offense, and he always puts himself in the right position on defense, where his quick hands and viselike grip make him a nightmare for average ball handlers. Paul is like an NFL cornerback who jams at the line of scrimmage on every snap. He gets his hands on guys and makes them play in an area the size of a phone booth. However, that strategy is not as effective against elite players with the size, speed, and skill to beat him at the point of attack. He is so fundamentally sound that he runs up the margins against bad players better than anyone, but there are no bad players the deeper you advance in the playoffs, particularly at point guard.

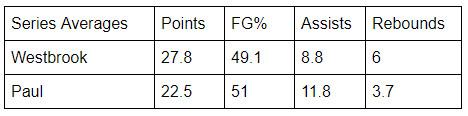

The second-round series between the Thunder and the Clippers in 2014, when Paul guarded Russell Westbrook, was a perfect example of that dynamic. Oklahoma City won a six-game classic remembered mostly for its dramatic road comeback in Game 5, when Paul made two brutal mistakes in the final seconds of regulation that wound up costing Los Angeles the game. While it would be unfair to single out one or two plays as the difference in such a tightly contested series, Westbrook clearly got the better of the matchup:

Paul was as efficient as ever against Westbrook, who has never been a particularly good defender. The issue for the Clippers was that Westbrook turned Paul into a traffic cone. The only way to slow down Westbrook is to use bigger and longer defenders who can contest his shot without giving him driving lanes to the basket. That’s what the Warriors did in the 2016 Western Conference finals, when Andre Iguodala and Klay Thompson held him to 39.5 percent shooting. Paul’s lack of size means he can’t impact a series defensively as much as an elite wing can.

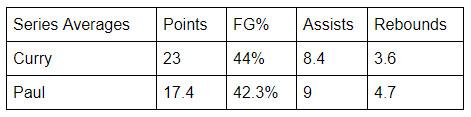

Paul is one of the best defensive point guards in the NBA, but a point guard’s ability to defend his position becomes less important in the playoffs, since teams often cross-switch bigger wings on them and switch screens more frequently rather than keep players on their original defensive assignments. Westbrook and Steph Curry can’t guard Paul any more than he can guard them; the difference is they can take over a series by going supernova on offense. Paul can’t consistently create easy shots against an elite defense, but he’s also too disciplined to take bad shots, which limits his upside against higher levels of competition. Paul has averaged more than 25 points a game in a playoff series only once, and it was in his most recent seven-game battle against the Jazz. Westbrook has done it nine times, and Curry has done it eight.

Paul’s tricks don’t work as well against his All-NBA peers. Even though the Warriors lost to the Clippers in the first round of 2014, Curry still got the upper hand on Paul in their individual matchup:

For as much as Paul should improve the Rockets in the regular season, he won’t change a potential postseason matchup with the Warriors much. He’s not big enough to guard Curry, Thompson, or Kevin Durant, all of whom can shoot over him as if he were a chair. And if neither Paul nor James Harden can guard Golden State’s perimeter stars, it puts a lot of pressure on their teammates. Daryl Morey has been stockpiling defensive stoppers since he acquired Paul, and Houston now has three in Trevor Ariza, P.J. Tucker, and Luc Richard Mbah a Moute. However, they are all inconsistent (at best) offensively, so playing them together would make life easy for the Warriors defense. Golden State creates a lot of matchup problems in a playoff series, and Paul doesn’t solve many of them.

On paper, CP3 is better than Paul George, one of the other major additions made by a Western Conference team this offseason with Golden State in mind. Paul has significantly better career numbers in every advanced statistic (PER, true shooting percentage, win shares, box score plus-minus), and he’s a more consistent decision-maker than George, who tends to float through the regular season. The difference in what they can do in the playoffs comes down to size. George has nine inches and 45 pounds on Paul, and he has the length and speed to defend all four of Golden State’s stars — something CP3 clearly can’t do. The Thunder can switch every screen George is involved in. He’s exactly the type of versatile defender a team trying to beat the Warriors’ needs, while his ability to spot up, knock down 3s, and serve as a secondary playmaker makes him a seamless fit in any offense.

Paul, on the other hand, needs the ball to work his magic. His über-efficient style of play would make him a better first option on an average team than George, but George would be a better fit in a complementary role next to Harden. Even though Blake Griffin and DeAndre Jordan are best in an uptempo system, the Clippers played at a glacial pace (17th in the league) with Paul running the show, because he preferred to walk the ball up the floor, survey the court, and make most of the decisions. When asked how the Clippers would be different next season, Doc Rivers said they would move the ball better without Paul. While Doc spins better than most politicians, there is some truth to what he said. Since Patrick Beverley will not demand the ball as much as his more celebrated counterpart, the Clippers will have a more diverse offensive attack. Paul controls everything his team does on offense, but no team who has given him the keys to the offense has even been able to make it to the conference finals, much less win a championship.

Playing in Houston will be the first time in Paul’s career when he is not the alpha and omega offensively. Taking on a smaller role makes sense for a player moving deeper into his 30s, but he doesn’t have the defensive versatility to cover up Harden’s weaknesses on that side of the ball. The Rockets still need two more two-way wings to match up with the Warriors, and they will get only more difficult to acquire if Houston gives Paul a supermax contract next offseason. Morey is a better GM than Doc Rivers, but building a championship team around Paul when he will soon be making more than $40 million a year will be difficult, if not impossible. While Harden and Paul should shatter efficiency records in the regular season, the real test will come in the playoffs, where Paul’s teams have traditionally underperformed. The biggest way he can help is by persuading Harden to play defense, since the Rockets will need more from their MVP candidate to make up for his new sidekick’s limitations.

Paul is rarely lumped in the same category as guys like Carmelo Anthony and Dwight Howard, whose postseason failures have practically defined their careers. Even though both have advanced further than him in the postseason, including knocking out Paul in the process — with Carmelo beating him in 2009 and Howard doing the same in 2015 — they don’t have advanced statistical résumés that make them immune from criticism. While Paul’s efficiency numbers suggest he’s one of the best players of all time, he’s not held to that standard when it comes to judging his career. The great irony is that he’s the prototypical pass-first point guard, yet his stats have bolstered his own résumé more than his team’s. Every basketball player should strive to be as efficient as Paul, but there’s still a ceiling to how good a player with his size and speed can be. Chris Paul has maximized every bit of his upside, and he does everything he can to help his teams win in the playoffs. It’s just not enough.