There is exactly one great scene in The Mummy. It isn’t the death-defying, zero-gravity, 64-takes-required airplane crash. It isn’t the epic final showdown between Tom Cruise’s treasure-hunting Nick Morton and the titular revivified Egyptian demi-god Ahmanet. It isn’t even the universe-building guided tour through Universal Studios’ hall of horror IP hosted by Russell Crowe’s Dr. Henry Jekyll. The very best scene is small and weird and classically Good Bad. After somehow awakening fully intact after the aforementioned plane crash, Morton visits a bar with the woman he has just saved, archaeologist Jenny Halsey (Annabelle Wallis). As Morton tries to make sense of how he survived, he sees a familiar figure behind the bar: the rotting corpse of his dead pal Chris Vail (Jake Johnson). Vail, who was transformed into a zombie ghoul by Ahmanet before being shot by Morton on the plane pre-crash — this movie is really convoluted — has somehow reappeared in a London bar, a festering comic relief back from the dead to haunt Morton. The scene is jarring and strange and absurdly funny, if transported from an utterly different film. Jake Johnson is a gifted comic actor, and his scenes with Cruise crackle in a way the rest of the movie does not. For five minutes, it feels like The Mummy might unwrap itself and let loose. It doesn’t.

We know now that The Mummy isn’t good, inspiring critical vitriol and the kind of phony Hollywood panic about the future of a franchise that keeps the grindstone spinning. But it also never quite gets bad enough. It’s a test case in how the vagaries of the industry have removed the opportunity for joyful disaster. For years, Hollywood operated with a kind of foolhardy arrogance that was not dissimilar to the music industry: make a lot of stuff, and if one out of 10 or 12 really hits, we’ll all get rich. But the production strategy in the movie business is vastly different now — there is, as we’ve been told time and again, no more middle. Gone are the rom-coms, the teen sex comedies, the best-seller adaptations. Want to feel old?

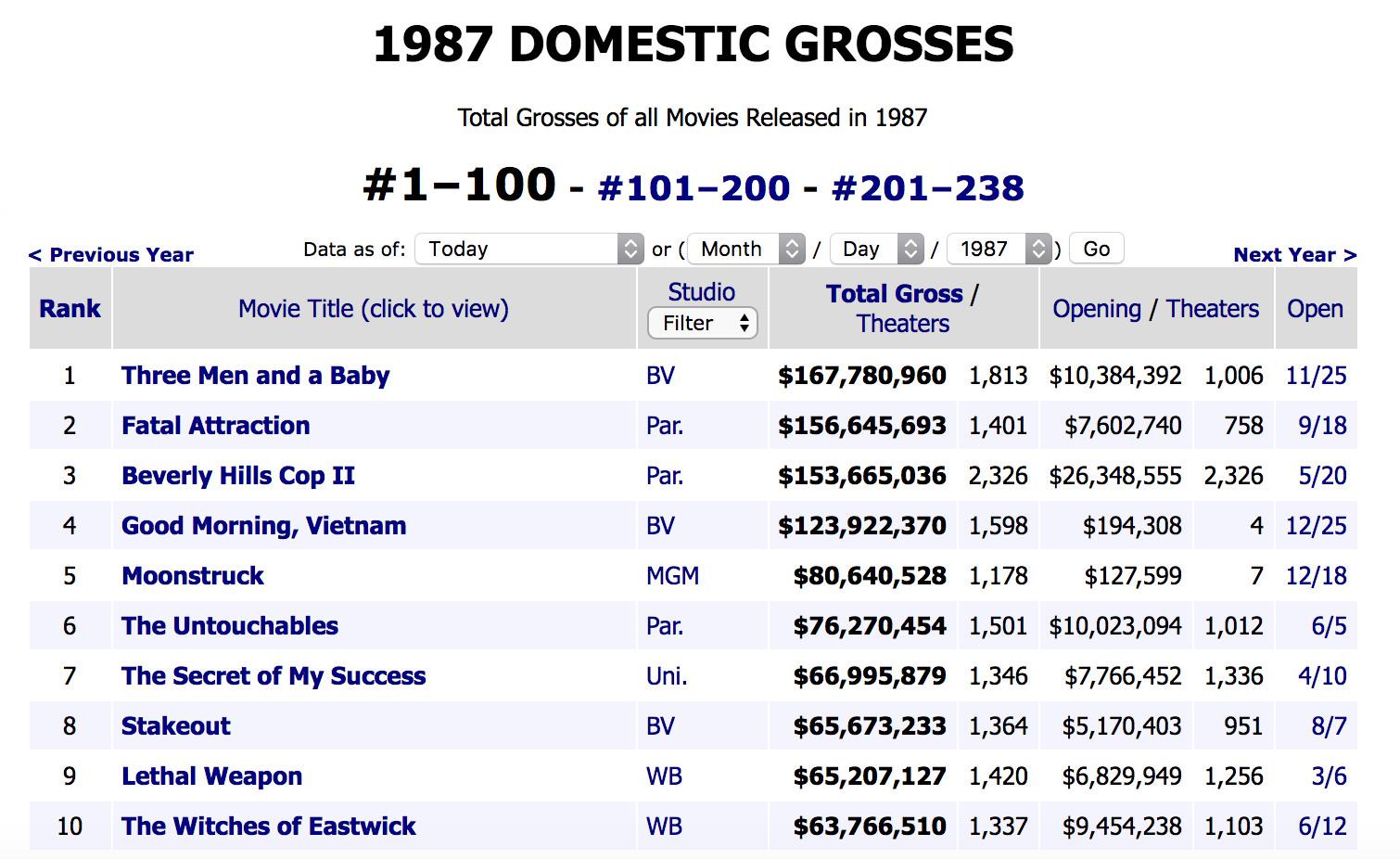

Those are the top-grossing films from 30 years ago. Among them is one sliver of intellectual property, the sequel to Eddie Murphy’s Beverly Hills Cop.

By comparison, let’s look at nos. 91–100.

Now there’s some good trash. Nestled among the Oscar-nominated flop Ironweed and Lasse Hallström’s early masterpiece My Life As a Dog (two full years after it debuted in Sweden) are the immortal sequel garbage Teen Wolf Too and Death Wish 4: The Crackdown, which represent a time when sequels didn’t mean "shared universe" so much as "How much money can I drain from this dying beast?" Don’t believe me? Here, look at this:

The seeds of the Good Bad Movie were planted in the ’80s, as studios became obsessed with drawing teen audiences. Without the sophistication or appetite for massive-scale comic book and science fiction stories, studios leaned into schlocky high-concept dramedies. Take another movie from the list above, Hiding Out. Here’s the log line: "A stockbroker on the run from the mob decides to hide out from them by enrolling as a student in high school." This movie stars then-22-year-old Jon Cryer, rocking a reverse-skunk dye job, as the stockbroker. It’s terrible and eminently watchable. The high-school-infiltrating conceit recalls numerous identity-swapping movies of the era: Just One of the Guys; Like Father Like Son; Can’t Buy Me Love; The Heavenly Kid. These movies are delightfully bad. But there is something that bonds them: Their stories are original. Someone, a screenwriter toiling on a lot somewhere, worked tirelessly to draw up the most hilarious high jinks that Kirk Cameron and Dudley Moore could engage in after switching bodies. This is not how Hollywood works now.

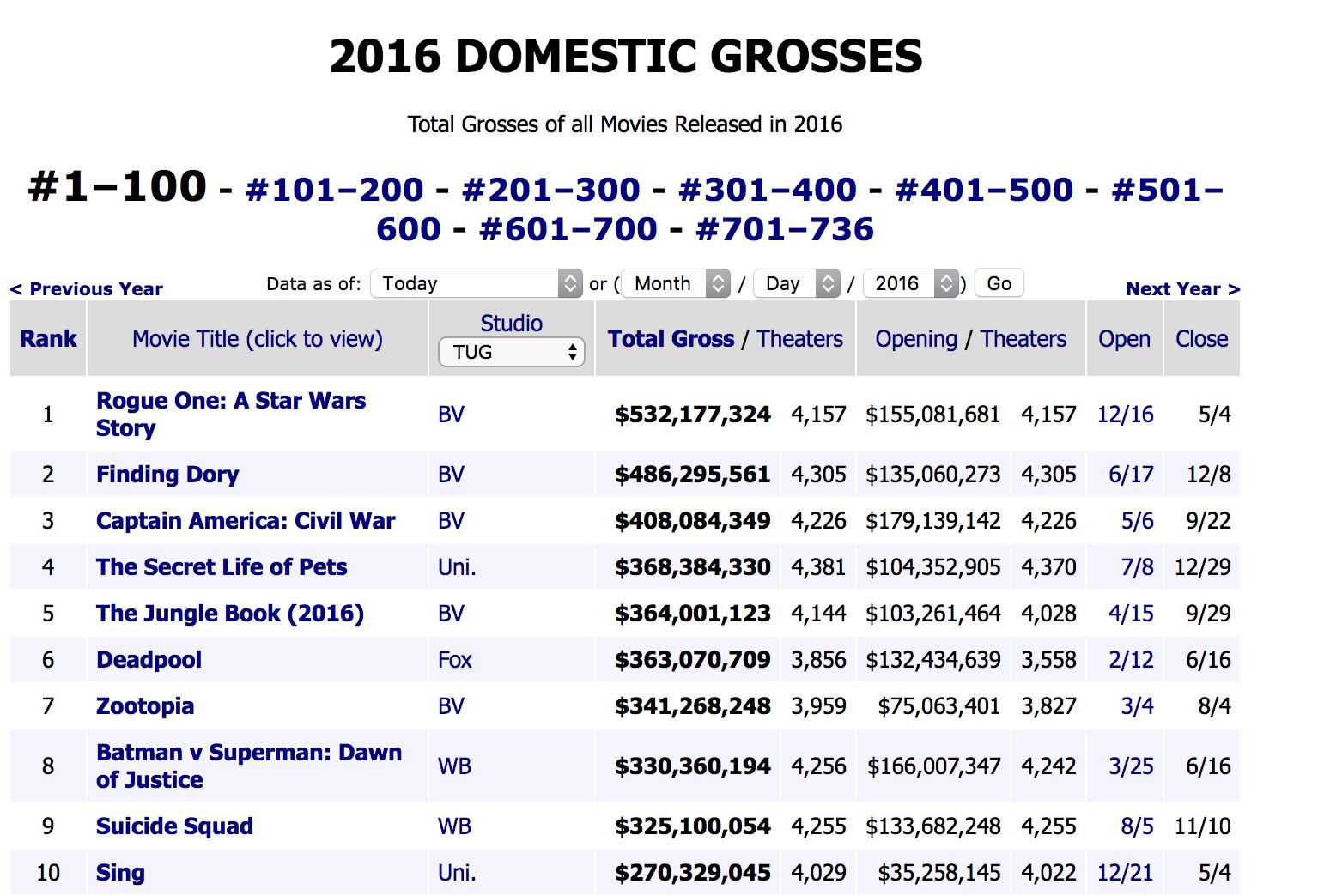

That’s a lot of IP. Last year, 63 of the 100 top-grossing movies were based on previously existing source material or real-life events. Six more are animated films. That leaves 31 original live-action stories. Compare that to 72 (!) original stories in 1987. Things have changed radically in Hollywood. Last week on Variety’s Playback podcast, Baby Driver director Edgar Wright echoed the vanishing nature of the original property: "Any original movie — [anything that] is not previously IP or a franchise — just the very act of getting it made is about persistence and vision," he said. "No original film is in the release calendar."

The point here is not that 1987 produced better movies, per se, though that case could be made. It’s that it produced better bad movies. Certainly the more original films that are green-lit in Hollywood, the likelier audiences are to see something they’ve never seen before. But original stories, even when they fail, can have a kind of entrancing, confounding quality. The best document for this phenomenon literalizes the feeling: Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas, and June Diane Raphael’s wonderful How Did This Get Made?

For context, here’s the bottom of the top 100 from 2016.

There’s not a single delightfully awful thing there. In fact, four of the year’s better reviewed movies — Oscar-recognized Moonlight, Hell or High Water, Florence Foster Jenkins — as well as The Witch appear here. Littered among them are the ignored Bridget Jones threequel, a not-fun-enough erotic thriller, Ben Stiller’s unwatchable, decade-late Zoolander 2, and a Kevin Hart stand-up film. This is not definitive proof of an industry change, merely an illustrative example of why our week celebrating Good Bad Movies feels more like a capstone rather than an acknowledgement of the zeitgeist. There are only four films released in the past decade on our 50 Best Bad Good Movies list, the most recent of which is Hercules, a colossal miscalculation on the part of Brett Ratner and the Rock. But even that movie feels like a stretch for this list, and it’s based on a previously existing, centuries-old story. Hercules could never be as fun as Road House because Hercules is easily understood to the masses, and on its worst day, it is still a movie about the Rock pummeling people.

Aside from The Mummy, the summer’s biggest failure at the box office is another Dwayne Johnson vehicle, Baywatch. The reasons for that are not only bound up in the dependence that Hollywood has on intellectual property, but also in the arch approach it takes toward some of these properties. The patient zero of meta-adaptation is 1995’s The Brady Bunch Movie, a clever and successful looking-glass satire of stilted ’70s sitcoms. These movies — desperately ironic and fourth-wall-demolishing — must either be ludicrously outlandish (21 Jump Street; The Lego Movie; anything Lord and Miller, basically) or not at all.

Hollywood has algorithmized itself with precision, and the removal of the middle hasn’t just hurt audiences looking for solid, adult entertainment — it has hurt those in search of dumb fun. (Unless The Fast and the Furious franchise is your idea of dumb fun.) As major studios reduce the number of films they produce, the rise of at-home viewing complicates how to evaluate movies. What’s left in theaters? This weekend, a fifth Transformers film, for example. Transformers: The Last Knight, Michael Bay’s latest installment in his alien-robot-warrior series, will reportedly be the franchise’s least successful stateside release ever. But you know where it’s working? China. And what did it knock off from the top of the box office in that country? The Mummy.