The day The Ringer launched, one year ago last week, I wrote a many-thousands-of-words explanation of how the Philadelphia Phillies had turned the corner on their rebuilding project. This article was inspired by a 24–17 start last year, their shrewd navigation of the Latin American amateur market to land future franchise cornerstone Maikel Franco and future closer Héctor Neris, and the trades that netted no. 1 starter Jerad Eickhoff and flamethrowing righty Vince Velasquez, who’d only weeks before thrown a three-hit, no-walk, 16-strikeout complete-game shutout.

With the Braves on a similar rebuilding track, the Marlins perpetually lost in the wilderness, and the Mets’ hopes holding by a series of untrustworthy elbow ligaments, the future hadn’t looked this bright for the Phillies since their 102-win 2011 season.

A lot of things can change for the worse in a year.

Even after taking a series from the Giants this past weekend, the Phillies are 19–35, 15.5 games out of first place, with the worst record and the second-worst run differential in the National League. They’re 27th in baseball in runs scored, and have the worst team ERA. Pitching coach Bob McClure has beefed with his catchers over pitch selection, Joaquín Benoit has beefed with manager Pete Mackanin over the structure of the bullpen, and every Mike, Nick, and Jackie in the Delaware Valley is either calling in to WIP-FM to gripe or making early plans for Eagles season.

So what happened? Is this a speed bump or will the Sixers be good again before the Phillies? Even if the Phillies are heading in the wrong direction, is there anything GM Matt Klentak can do in the short term to stop it?

The short answer is that the Phillies’ pitching staff was supposed to be the strength of the team, and that hasn’t been the case. The offense was always going to be bad, but the pitching was supposed to carry the team up close to .500. Last year, Jeremy Hellickson pitched 189 innings with a 113 ERA+, and Eickhoff pitched 197.1 innings with a 115 ERA+. Velasquez and former first-rounder Aaron Nola both struggled to get outs and stay healthy last year, but they showed the promise to be even better than Eickhoff. Clay Buchholz, a punchline in 2016 but a well above-average pitcher in 2015, came over for organizational filler in the offseason. Veterans Benoit and Pat Neshek promised to add bullpen depth, and former top-100 prospect Jake Thompson was ready for an extended look should someone go down.

The pitching struggles have partially been the result of injuries: Nola missed time early in the season with a back strain, Velasquez is out with elbow trouble, Benoit has a sprained knee, and a torn flexor pronator mass will probably knock Buchholz out for the season. But it’s not entirely the result of injuries. Of the eight Phillies pitchers to make a start this year, only Ben Lively has a better-than-average ERA, and he’s made only one start. The only other Phillies starter with an ERA below 5.00 is Hellickson, whose three-earned-run, 5.1 IP start on Sunday raised his ERA to 4.50. Eickhoff has a 6.94 ERA in his past seven starts, over which he’s allowing a .342/.399/.493 line, turning the average hitter into José Altuve, give or take.

Lively’s seven-inning start on Saturday marked only the second time since May 6 that a Phillies starter recorded an out in the seventh. That’s not only bad for its own sake — it means the starters aren’t pitching well — but it’s handed more innings over to the 28th-ranked bullpen in the game by fWAR. And not the good parts — Neshek’s been dominant (2 ER in 21.1 IP) and Neris and Edubray Ramos have been fine — but the soft underbelly of unmemorable quad-A arms, like Jeanmar Gómez, Joely Rodríguez, and Mark Leiter, that have filled out the rest of the bullpen.

All Klentak can do at this point is determine which members of his pitching staff are salvageable. Buchholz, a 32-year-old free-agent-to-be, is probably a write-off, as is former closer Gómez, who posted a 4.85 ERA even as he saved 37 games last year and whose 2017 ERA is north of seven. The Phillies missed their chance to cash in on Hellickson, first at last year’s trade deadline, then again in the offseason, when the former Tampa Bay and Arizona right-hander accepted a qualifying offer instead of leaving and netting a compensation pick for the Phillies. Even so, Hellickson’s close enough to league average that he could fetch some lottery ticket of a prospect from a pitching-starved contender at the deadline, as could Neshek.

The one thing that hasn’t changed in the past year is that the success or failure of the Phillies’ pitching staff for the near future will come down to Velasquez, Nola, and Eickhoff. For Velasquez, the question was always less about the top-end stuff he displays on his best days and more about his durability, and so far, he’s answered that question in the negative. Nola’s struggles are more annoying because he was drafted as a polished, quick-moving starter out of LSU, the college pitcher equivalent of a frozen pizza. He was supposed to be a reliable no. 3 starter by now, but he’s still struggling. The good news is that he’ll have plenty of time to figure it out in the majors, because with the team 16 games below .500 on June 5, he can’t make things any worse.

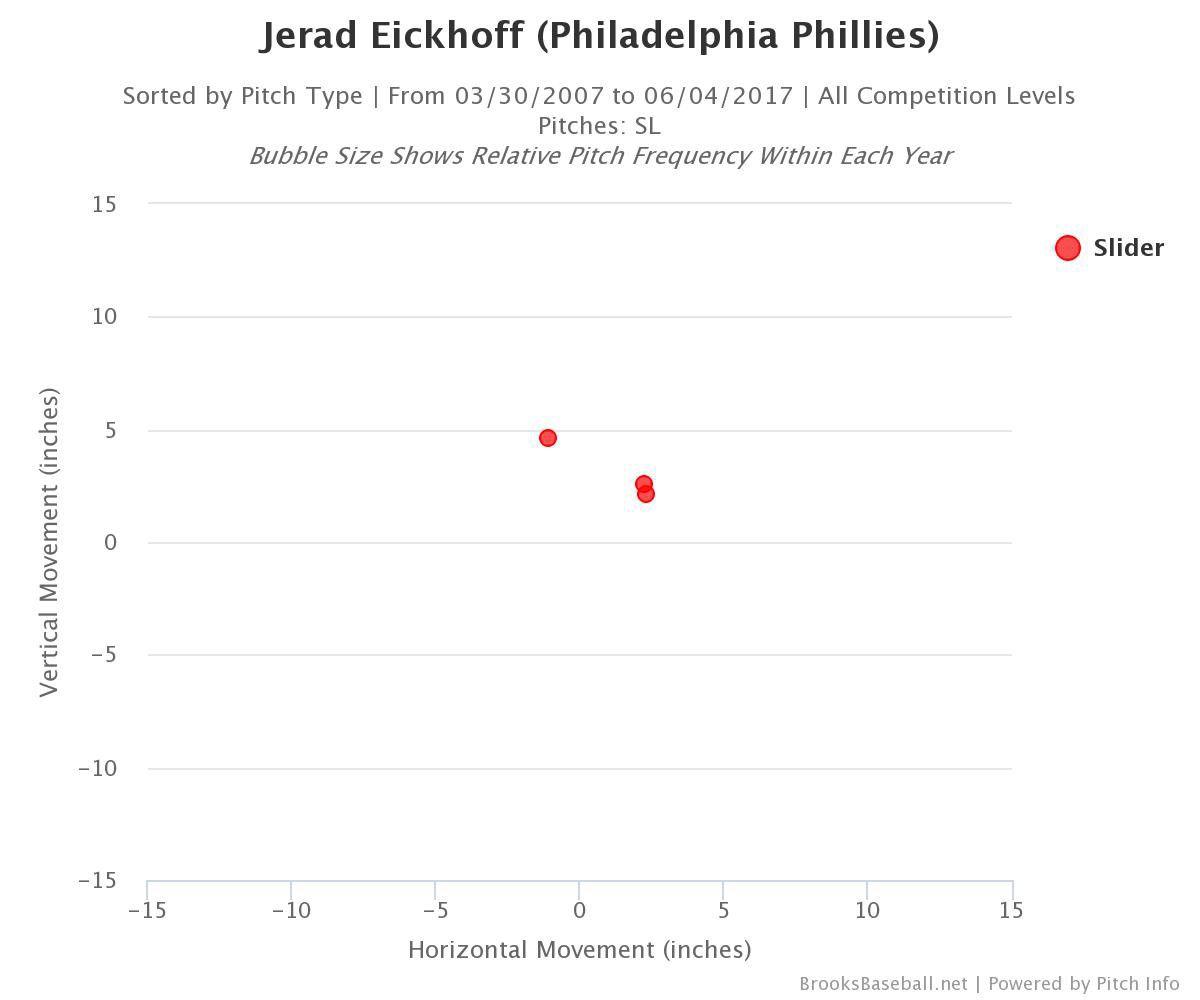

Eickhoff’s struggles come down to the slider. In 2015 and 2016, it was his out pitch, and he threw it about once every six pitches. But this year, it’s different.

It’s more than 2 miles an hour faster, for starters, and it’s breaking 3 inches less horizontally and 2 inches less vertically. It’s been the difference between Eickhoff pitching like the guy you’d start in Game 2 of the NLDS and a guy you’d think about demoting to Triple-A.

Beyond that trio, the Phillies still have some young high-minors starters to call on, because they got pitchers back for just about every veteran they’ve traded away since 2011. In addition to Thompson and Lively, Zach Eflin and Nick Pivetta got some playing time earlier this year. Thomas Eshelman, the former record-breaking college control artist, has a 1.40 ERA in five starts Triple-A. Former no. 1 overall pick Mark Appel, who came over from Houston with Eshelman, Velasquez, and two others in the Ken Giles trade in 2015, might be cooked, if his 6.14 ERA at Triple-A is any indication, but he’s still down there. If Velasquez’s injuries keep piling up and Eickhoff never rediscovers his slider and Nola continues to struggle, Klentak will have to find a new crop of pitchers to build around, but that Triple-A depth should allow him to fill out the back of the rotation without going outside the organization for help, which would buy time for the pitching staff to sort itself out.

One thing they could do is get their pitchers some help. McClure’s been the fall guy before — he had the misfortune of being hired as the pitching coach on the Bobby Valentine Red Sox of 2012, and didn’t even make it to the end of that season — but McClure might just not be in the class of miracle-working pitching coaches like Pittsburgh’s Ray Searage and Cleveland’s Mickey Callaway. It isn’t clear that he’s being actively detrimental.

Cameron Rupp, the dadlike, power-hitting Texan who took over behind the plate for the stalwart Carlos Ruiz last year, presents more tangible problems for Phillies pitchers. Rupp hits well for a catcher: .230/.321/.393, good for a 91 OPS+, but he’s the third-worst defensive catcher in baseball with at least 1,000 chances, according to Baseball Prospectus. Backup Andrew Knapp’s been a little better, but still below average, though his 18 career starts behind the plate don’t begin to constitute an appropriate sample size. It wouldn’t be a long-term solution, as Jorge Alfaro is being groomed in Triple-A as the team’s catcher of the future, but in the short term, a better pitch caller and framer would be able to steal some strikes and instill confidence in this young pitching staff.

Rupp’s shortcomings point to another problem, too: The offense was supposed to suck this year, but it wasn’t supposed to suck forever.

Injuries have hampered Howie Kendrick, acquired in a trade from the Dodgers in the offseason, while free-agent signing Michael Saunders (72 OPS+) has just been plain bad. Franco backed up from a 130 OPS+ as a rookie to 95 in 2016, and this year his OPS+ is down to 73. Rule 5 pick-turned-All-Star center fielder Odúbel Herrera has been moved around the lineup and was briefly benched last week as he’s hit .234/.276/.373. I could go position by position, but instead of belaboring the point, I’ll just say that the team’s struggled partly because Daniel Nava missed about two weeks with a hamstring injury. That’s right: This offense is so bad it missed Daniel Nava.

Herrera’s struggles have been the most puzzling and most problematic. Just this past offseason, the Phillies signed him to a five-year extension with two team options, a deal that, money-wise, puts him right around Miami’s Christian Yelich and Pittsburgh’s Gregory Polanco. And yet he’s just cratered offensively this season. Herrera had shown an incredible ability over his career to maintain consistent production while changing his approach. For instance, he just decided he wanted to walk like Joey Votto last year, and for a few weeks, he did. In two games since he was restored to the starting lineup over the weekend, Herrera torched the Giants, going 5-for-8 with four doubles, a home run, and six RBI. Maybe this is the first sign of the slump being busted, and all he needed was a wake-up call. But if it isn’t, that’s a problem: Of all the talented youngsters the Phillies have acquired in the past two-plus seasons, Herrera’s the only one the team’s made a long-term commitment to.

Franco’s lost power from year to year since his major league debut in 2014, but even if he never ends up repeating his 129 wRC+ from 2015, the most important position players on the next good Phillies team are yet to come. Outfielder Nick Williams, acquired with Eickhoff, Thompson, and Alfaro in the Cole Hamels deal, has run hot and cold — he’s currently hitting .280/.319/.503 at Lehigh Valley, but he’s repeating Triple-A after he posted a .287 OBP last year. Alfaro’s hitting just .267/.293/.378, and last year’s no. 1 overall pick Mickey Moniak is struggling to adjust to pro ball.

The biggest concern among Phillies prospects surrounds shortstop J.P. Crawford, a polished defender who’ll take a walk and hit for decent power at the position. Crawford’s been around the top 10 on global prospect lists for two years, and seemingly a step away from the majors ever since he hit .265/.354/.407 at Double-A Reading as a 20-year-old in 2015. This year, Crawford reached base in 17 consecutive games at one point, but in between the odd single or walk, he’s hit just .193/.315/.257.

We’re not supposed to freak out about minor league numbers, but Crawford’s been on the cusp of the majors for more than a year, and he’s slugging .257. Not only that, he slugged .318 in half a season at Triple-A last year, after slugging just .390 in 36 games at Reading, one of the best hitter’s parks east of Coors Field. Crawford says he’s turned a corner — and believe it or not, those numbers were even worse a month ago — but it’s still hard to be optimistic considering where Crawford is now and where he was expected to be by now: alongside Herrera at the top of the Phillies’ lineup.

The most frustrating thing for Phillies fans is that Klentak doesn’t have an obvious card to play. Usually when a team’s struggling, the refrain is that they should trade everyone and play the kids, but the Phillies just spent five years trading everyone, and they are playing the kids. Many of the players who are struggling right now have little trade value anyway. Franco, for instance, was a hot commodity two years ago, but now he’s a 24-year-old who has had two seasons in the majors already, is getting worse, and thanks to his lack of foot speed, might have to move to first base soon.

Amid the struggles, Klentak pointed out that this kind of swoon is common for rebuilding teams, and even players who end up becoming major contributors later on often struggle early in their careers. That seems to describe outfielder Aaron Altherr, who missed the first half of 2016 with a wrist injury and hit just .197/.300/.288 when he returned. But this year, the Rhineland Rocket has exceeded all reasonable expectations by hitting .283/.370/.520 and looking like the team’s left fielder of the future.

Annoying as it is to be told to take the long view when your team is 15.5 games out of first place, it’s true. Any major shake-up now would not only remove the opportunity for struggling players to bounce back, it’d be born out of frustration, the transactional equivalent of Ryan Madson kicking a chair and landing on the DL with a broken toe.

The only thing left to do is hope that those future franchise cornerstones — Crawford, Herrera, Eickhoff, Nola, Velasquez — snap out of it, because right now, there’s not really anything else the Phillies can do.