Two Little Birds

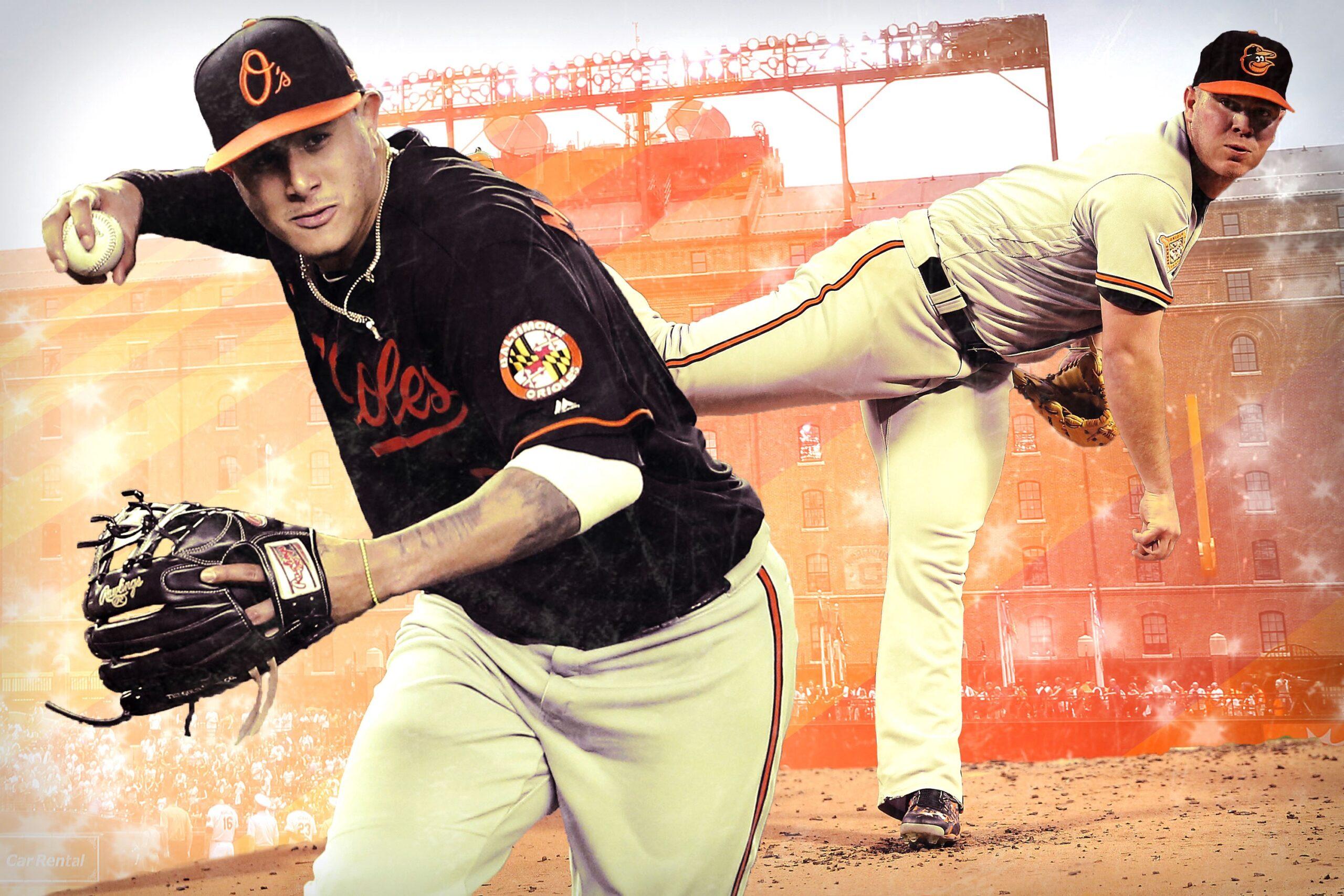

Manny Machado and Dylan Bundy represent a rare double-whammy for the Baltimore Orioles: Back-to-back first-round picks who lived up to their potential. But despite playing vital roles for one of the best teams in the American League this season, they took divergent paths to the pros.

The Baltimore Orioles’ travel chess set couldn’t look any more low-rent: chunky plastic pieces with a flexible rubber mat with green and white squares. But in a visiting clubhouse where more than two dozen guys have a ton of time to kill, it’s a hub of activity. A rotating cast of players, plus first-base coach Wayne Kirby, takes turns in a series of grudge matches, but before a Saturday evening game in Houston, pitcher Dylan Bundy and third baseman Manny Machado are up. Machado, long and broad, leans on one arm, bending over the table, while the more compact Bundy keeps all six legs on the floor, staring at the board like it’s a particularly intransigent question on a high school algebra test.

Some variation of this showdown happens before every game in every clubhouse in the league. It’s chess in the Orioles’ locker room, but elsewhere it’s ping-pong, Monopoly, or one of a hundred different card games. Unlike most clubhouse games, which are ultimately a way for pathologically competitive 20-somethings to lock horns and therefore involve trash talk, complaining, and swearing in at least two languages, this game resolves quietly. Bundy checkmates Machado and, with a nod, retreats to his own locker, as do Machado and the two or three spectators. It’s all very routine.

Bundy met Machado for the first time at a wood bat tournament when they were 16 or 17. Machado, despite being a year ahead in school, was only four months older, so they wound up in the same age bracket. By that point, both were on professional teams’ draft radar and were starting to scope out the competition to learn who they might see again in pro ball. Their first in-person meeting went better for Bundy than it did for Machado.

“He was a hell of a player,” Machado said. “I think we faced him one time and he had 13 strikeouts in six innings or something like that, which was crazy.”

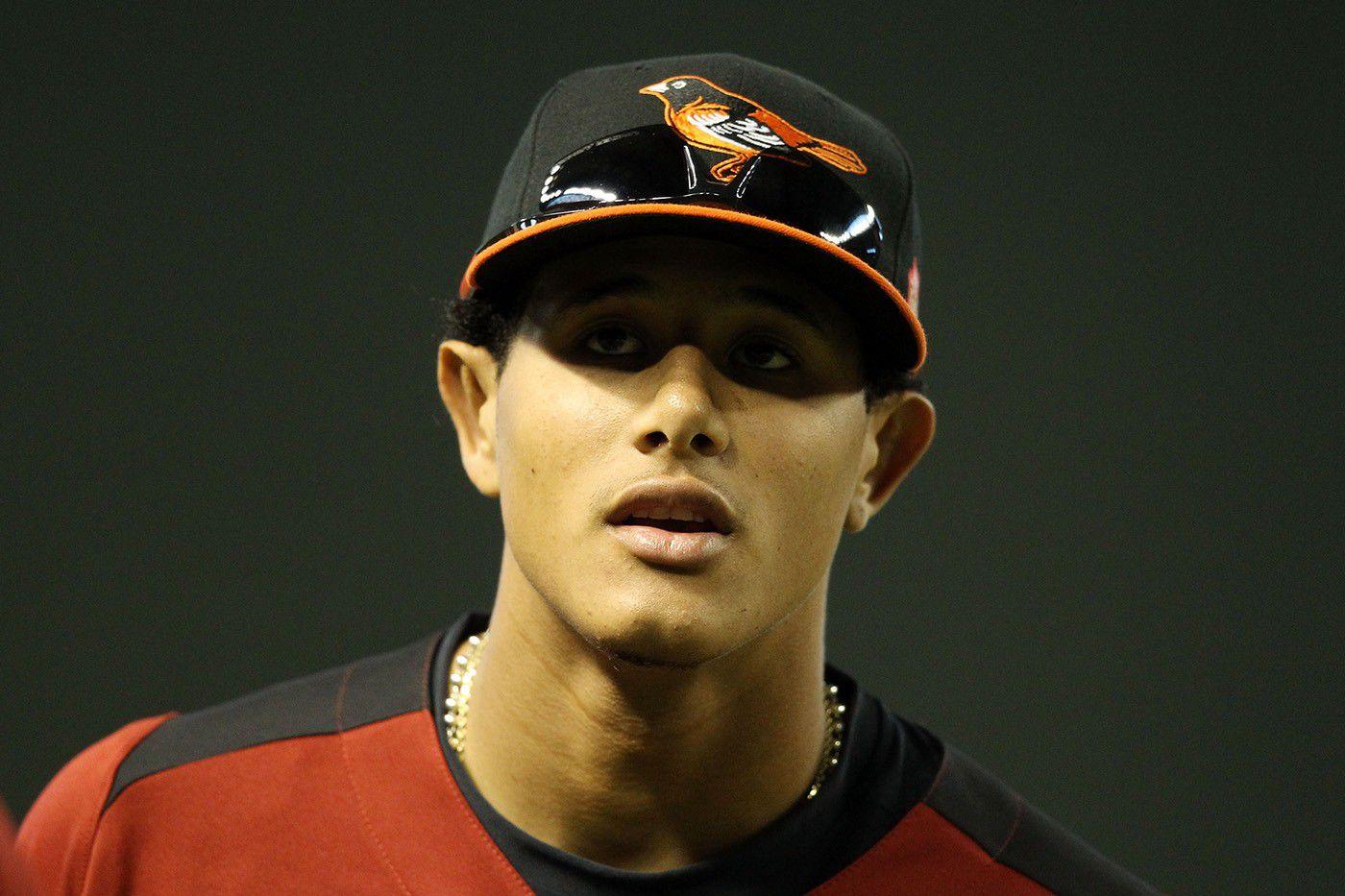

Machado figured out how to hit just about everyone else; as a big, power-hitting Dominican American shortstop from Miami, he was drawing comparisons to Alex Rodriguez by the time he finished high school. In 2010, the Orioles made Machado the no. 3 pick in the draft and offered him a $5.25 million signing bonus, the highest sum they’d ever paid to a high school draft pick.

Bundy joined the organization a year later. High school pitchers are almost comically unpredictable as draft prospects — in the 52-year history of the draft, a high school right-hander has famously never gone with the no. 1 pick — and even then, Bundy wasn’t exactly a prototypical high school pitching prospect.

Most big high school right-handers are, well, big. Josh Beckett (no. 2 overall in 1999) is 6-foot-5. Tyler Kolek (no. 2 overall in 2014) is 6-foot-5, 260 pounds. Lucas Giolito, who might have gone first overall in 2012 if not for a sprained UCL and a big bonus demand that caused him to fall to no. 16, is 6-foot-6, 255 pounds.

Bundy came out of high school with a fastball that touched triple digits, a devastating cutter, a plus curveball, and unusual polish for an 18-year-old. But he’s only 6-foot-1. Conventional wisdom is that bigger pitchers are more durable, and they definitely have an easier time throwing downhill and releasing the ball as close to the plate as possible. However, Bundy’s repertoire and command made him look like the rarest of amateur pitchers: a relatively safe bet to become a big league contributor who nonetheless had top-of-the-rotation upside.

In one of the strongest drafts of the 2000s, Baltimore took Bundy and gave him a $4 million bonus and a five-year major league contract. Anthony Rendon, Francisco Lindor, Javier Báez, José Fernández, Sonny Gray, Joe Panik, Jackie Bradley Jr., and Michael Fulmer came off the board in the next 40 picks.

Bundy and Machado have been not only linked, but cast as the future of the Orioles since they were teenagers. That’s exactly what they became: Bundy is the no. 1 starter and Machado the top position player on a team that’s a game out of the wild card and very much in the thick of the pennant race, despite a recent 2–9 skid. But even though they started and ended in the same place, Bundy and Machado have lived very different lives since their big league debuts.

Those back-to-back top-five selections transformed Baltimore’s otherwise bare farm system. Before the 2012 season, Baseball Prospectus rated Bundy and Machado the no. 6 and no. 8 overall prospects in baseball, with Jonathan Schoop (no. 85) as the only other Oriole in the top 101. No other team had two top-10 prospects, and only the Mariners (Jesús Montero and Taijuan Walker) and Pirates (Gerrit Cole and Jameson Taillon) had two players in the top 20.

Coming up through the Orioles system presented specific narrative challenges to both Machado and Bundy. For 44 of the team’s first 50 seasons in Baltimore, the left side of the Orioles’ infield featured at least one Hall of Famer — either Brooks Robinson or Cal Ripken — plus a couple of Hall of Very Good players, like shortstop Mark Belanger and third baseman Doug DeCinces. A 40-plus-WAR career was always the expectation for Machado.

Bundy, meanwhile, was tasked with overturning 20 years of history, in which the Orioles’ farm system produced just about nothing in the way of starting pitchers. Since Mike Mussina debuted in 1991, the Orioles have produced Erik Bedard and an argument about whether Chris Tillman, who was a Mariner up until Double-A, and Wei-Yin Chen, who spent five seasons in NPB, count as “homegrown.”

It’s not for lack of investment, either. From the 1994 strike through 2010, the Orioles spent 14 first-round picks, five of them in the top 10, on pitchers. Of those, only five even made it to the majors, and only Brian Matusz, a no. 4 overall pick and two-time top-20 prospect who turned out to be a LOOGY, has a positive career WAR.

As Bundy and Machado both shot through the minors, they still knew each other mostly by reputation and during their time in spring training.

“There’s 50 or 100 guys in a small area, so you get to know everybody pretty well,” Bundy said. “Then the guys who are a level above or below you, you hear their names and see box scores.”

In 2012, as the Orioles chased their first playoff appearance since 1997, that changed, and the two top prospects took the field together for the first time.

In early August 2012, veteran third baseman Wilson Betemit went down with a wrist injury and Machado, despite having played two games at third base in his entire career, was called up to replace him. Bundy took Machado’s place at Double-A Bowie.

“It was awesome, just being in the big leagues was an unbelievable experience,” Machado said. “To come up and for them to have so much faith in me in the middle of their first pennant race in 15 years, it gave me the encouragement that I needed.”

That Orioles team had Adam Jones and a bunch of good players, but no other real stars. Machado quickly made good on the hype and became a household name nationwide, thanks mostly to his precocious defense.

“I was just playing the game,” Machado said. “I was just excited to be in the big leagues, to be honest, so I didn’t worry about anything else. I was hitting eighth or ninth, so it really didn’t matter what I did with the bat as long as I played good defense, so that was my main focus.”

Machado had just turned 20, and because his July 6 birthday falls a week after Baseball-Reference’s cutoff date, he’s credited with playing part of his age-19 season in the majors, a distinction shared by only 10 other active players. One of them is Bundy, who debuted on September 23, 2012, two months shy of his own 20th birthday.

While Machado went on to win two Gold Gloves, hit 35 home runs twice, make three All-Star teams and earn two top-five MVP finishes by age 24, Bundy spent the next three years in the wilderness.

The issues began in 2012, when Bundy, whose out pitch in high school was a high-80s cut fastball, was scything through three minor league levels. That summer, it came out that the Orioles had forbidden him from throwing the cutter during his first minor league season. That’s not in and of itself unusual; teams will often have a prospect put a pitch on the shelf to force him to develop his weaker offerings. But when it came out that Orioles GM Dan Duquette thought the cutter was bad for Bundy’s arm and wanted him to scrap it permanently — this only a year after the Orioles drafted the cutter-happy Bundy in the top five — a minor scandal ensued.

It seemed at the time like an organization with an unparalleled track record of screwing up pitching prospects was doing it again, this time to a pitcher who came out of high school looking un-screw-up-able. Then Bundy started the 2013 season sidelined with forearm soreness, a nebulous affliction that’s often a precursor to a torn UCL. And in late June it became official: Bundy needed Tommy John surgery, ending his 2013 season before he’d thrown a pitch.

Bundy says he stayed positive throughout his rehab thanks to an unfortunate coincidence: His older brother Bobby, also an Orioles minor leaguer, suffered the same injury a month later.

“We were able to go through Tommy John together and live in the same apartment in Florida and rehab together,” Bundy said. “You’ve just got to stay positive the whole time and look up success stories, not the failures. Read those and you’ll see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Bundy returned to action in June 2014 and made nine starts before a lat strain sidelined him for the rest of the year. In 2015, he made it back to Double-A, but suffered a calcium buildup in his shoulder that ended his season in late May (outside of a two-inning stint in the Arizona Fall League). Since his cameo in 2012 featured two relief appearances in which he didn’t strike out a batter, it took Bundy until April 21, 2016, his seventh major league appearance, to notch his first big league strikeout. On May 27, he picked up his first win, and on July 17, he allowed four runs in 3.1 innings in his first big league start, almost four years after he replaced Machado on the Double-A roster.

“I didn’t get too bad, but there were times when I was like, ‘Dang it, I don’t know if I’m ever going to throw 95 again,’” Bundy said. “But I just continued to keep my head up and continued to do my rehab.”

Bundy finished 2016 with a 4.02 ERA in 36 appearances, 14 of them starts. After throwing 65.1 innings across all levels from 2013 to 2015, Bundy threw 109.2 innings in the majors in 2016.

Bundy was right about one thing: He’s not consistently hitting 95 anymore. After throwing in the high 90s and maxing out at 100 in high school, then sitting at 95 and maxing out at 97 in 2012, Bundy’s fastball has averaged 92.2 miles an hour in 2017, with his fastest offering coming at 95.7.

Despite the drop in velocity, and despite a strikeout rate of just 6.2 K/9, Bundy has been Baltimore’s best starter in 2017, with a team-leading 145 ERA+ and — perhaps most importantly — 71.2 innings pitched in 11 starts.

“My goal is to make 30 starts this year,” Bundy said. “Mainly, as long as I feel good and take care of my body, hopefully I can make 30 starts and continue to grow as a pitcher in the mental side of the game. Not so much making pitches nastier, but locating them better.”

Still only 24, Bundy could yet become the Orioles’ best homegrown pitcher of the past 20 years. The Orioles, despite lacking a no. 1 starter, are still the winningest team in the American League since 2012, so they can win even if Bundy doesn’t turn into the next Mussina, but it would make life easier if he did.

“You need someone like that, and he definitely has everything in the tank to get there,” said Machado. “He’s still young, he’s still learning the hitters. He just needs to continue doing what he’s been doing and not really worry about anything else. Every single day you’re working at fastball command. If you can command the fastball and throw it where you want to at any time, you can control an at-bat and throw your off-speed stuff to get weak contact or strikeouts.”

Bundy’s been able to live with the velocity drop because after not throwing a single cutter in 2016, he’s brought back his old out pitch. Only now he’s adjusted how he holds the ball, trading velocity for movement, and he’s calling it a slider.

“It’s pretty much the same pitch, minus the velo,” Bundy said. “When I was in high school I was throwing it 89, 90 miles an hour. Now it’s 82–84, and it’s just a tad bigger than it was in high school. I’ll take it — it’s a swing-and-miss pitch, a ground-ball pitch.”

About one pitch in five this year has been a slider for Bundy — 239 in all — and it isn’t causing him any discomfort in his surgically repaired elbow.

“So far so good. I haven’t felt anything on my forearm that I felt before,” Bundy said. “As long as I don’t feel anything, I’ll keep on throwing it. If I do end up feeling anything, I’ll shut it down immediately and continue to throw my three-pitch mix.”

While Bundy has hit a groove, Machado is struggling for the first time since his injury-plagued 2014 season. He’s battled beanballs against Boston and, despite career highs in walk rate and hard-contact rate, he’s hitting only .210/.292/.415, for an 88 wRC+. But Machado says he hasn’t changed his approach or swing, nor does he think pitchers are attacking him differently. In fact, he’s completely unconcerned with his underlying numbers.

“That’s you guys coming up with some dumb-ass stats,” he said. “I’m just playing baseball. It’s just like any other year. For five years it’s been the same. It’s just a matter of [hits not] falling now, and that’s just part of the game.”

Machado’s distaste for the numbers notwithstanding, an 86-point drop in BABIP from last year (.309 to .223) seems to back him up. He’s seen a decline in line-drive percentage, but that should be offset by hitting the ball harder overall.

At age 24 and with such a long track record of big league success already behind him, Machado’s season looks more like a bad couple of months than a permanent slide off the track to the Hall of Fame that, without the least bit of hyperbole, he’s currently on. And just like when he was a rookie, he’s still playing world-class defense at third base.

Five years after they were both top-10 prospects, Machado and Bundy are now 24 years old, the best position player and pitcher, respectively, on a contending Orioles team. They’ve made good on the hype, and while Bundy’s lost years will keep him from reaching free agency until after 2021, Machado’s already deep into arbitration, making $11.5 million this year, with a chance for a couple hundred million more when he hits free agency after next season. So if someone from the future had visited them on draft day and offered them their current careers, what would they have said?

“I would’ve thought you’d been wrong,” Bundy said. “When I was 18 or 19 years old I wouldn’t have thought my arm would ever get hurt.”

Machado was equivocal until I rephrased the question: Is he happy with how his career’s turned out?

“Wouldn’t you be? I’m in the big leagues for six years and I’m enjoying every moment of it. I’m playing the game I’ve always dreamed of playing, and I’m beyond excited.”