When baseball analysts say that one-run wins and losses largely hinge on luck, this is what they mean.

That’s a 1–0 pitch from Rangers reliever Sam Dyson to Mariners third baseman Kyle Seager in the eighth inning of a tie game on May 7. According to the onscreen display, the pitch was in the strike zone. We can get more specific than that, though. According to Pitch Info’s called-strike probability — which is based on the season, the count, the location (relative to the batter’s personalized zone), the pitch type, and the handedness of the pitcher and batter — that pitch would be called a strike 93.2 percent of the time. This instance was one of the other 6.8 percent.

That ball call may have proved pivotal. Historically, when Seager has started a plate appearance 1–1, he’s produced a .673 OPS, with a home run every 37 at-bats. When he’s started a plate appearance up 2–0, he’s produced a 1.034 OPS, with a home run every 23 at-bats. The next pitch Seager saw in this particular plate appearance was, admittedly, lousy. But if the count had been even, the pitch might have been less lousy, or Seager might have been slightly too slow to do what he did.

That solo shot gave Seattle a lead in a 4–3 victory, the Rangers’ second-to-last loss before their 10-game winning streak started. On another day, in another place — 93.2 percent of days and 93.2 percent of places — that 1–0 pitch would have been called a strike, and the game’s outcome could have been different. Hence that "largely luck."

But not entirely luck. That called-strike probability doesn’t account for the catcher — in this case, Jonathan Lucroy. Let’s look at another pitch, this time from September 2013. Like the pitch from Dyson, this is over the plate and approximately at the knees, just a little lower, a little farther toward the outside edge, and a little less likely to be a strike (80.0 percent probability, per Pitch Info). Yet this time, the call goes against the batter.

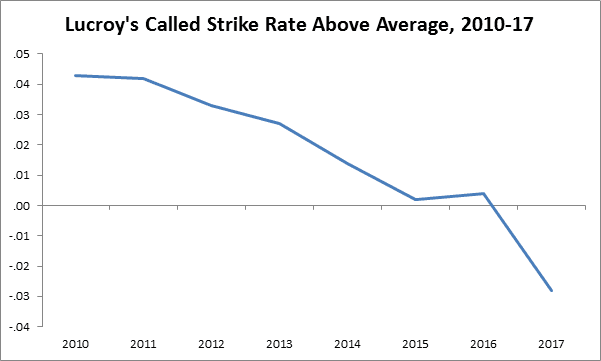

Lucroy is the catcher in that clip, too. Based on the numbers, though, he’s now nowhere near the receiver he was during his defensive prime in Milwaukee. The outcomes of the two called pitches embedded above reflect a sweeping reversal in Lucroy’s results.

Not so long ago, Lucroy was one of the faces of pitch-framing, a go-to guy for media members hoping to talk strike-stealing technique.

As recently as 2013, Lucroy led baseball in runs saved from framing. This year, he leads baseball in runs lost from framing. Coupled with his disappointing (albeit fast-improving) performance at the plate — .277/.320/.412, about 5 percent below league average — that framing decline has reduced him from an MVP-caliber contributor a few years ago to a replacement-level player so far this season, according to Baseball Prospectus (whose wins above replacement player, unlike Baseball-Reference or FanGraphs WAR, does factor in framing). That’s not what the Rangers wanted when they traded two top-50 prospects, Lewis Brinson and Luis Ortiz, in the deadline deal Lucroy headlined last August.

Granted, four years is enough time for the league to experience a lot of leaderboard turnover. In 2013, Andrew McCutchen, Carlos Gomez, and Chris Davis were among baseball’s best position players, and Adam Wainwright, Cliff Lee, and Félix Hernández were unquestioned aces. But Lucroy’s decline is particularly precipitous. Although he hasn’t yet turned 31 — an age at which framing tends to decline only gradually, especially for modestly sized players like the 6-foot-listed Lucroy — he’s gone from the best to the worst framer while much older catchers who also excelled in that area in 2013 (including Russell Martin, Jeff Mathis, Brian McCann, Chris Stewart, and Yadier Molina) have remained roughly average or better. Lucroy’s throwing has only improved with age, but his framing shortcomings have hurt him much more than his ability to deter or retire would-be base stealers has helped.

Lucroy’s receiving — as measured by called strikes above average (CSAA), a Baseball Prospectus rate stat — has been in descent for some time, but the floor has fallen out of his framing this year. Framing tends to be stable in small samples and consistent from season to season, and no other regular catcher has seen his CSAA shift as substantially as Lucroy’s in either direction compared with 2016 (although Buster Posey’s similarly perplexing decline comes close).

Rangers pitchers have thrown the game’s second-highest percentage of pitches with opposing hitters ahead in the count, and while that’s not all on Lucroy, he hasn’t helped. With Lucroy due for free agency at the end of the season and the Rangers — who have bat-first Triple-A catcher Brett Nicholas and Double-A catching prospect Jose Trevino positioning themselves for playing time in 2018 — in the running for a wild-card slot, Lucroy’s receiving could dictate his next contract and help determine the playoff picture. So why has Lucroy’s framing faded so far and so fast?

We can probably rule out a few factors. For starters, we can’t pin the bulk of the blame on the pitchers. One might suppose that leaving Milwaukee and having to work with a new pitching staff could have hurt Lucroy’s receiving, but if that were the culprit, we’d expect him to have struggled even more after last year’s midseason trade, which wasn’t the case. (Lucroy’s framing rated a hair above average in Texas in 2016.) One might also speculate that the Rangers’ arms this season have been especially hard to handle, even relative to some of the lousy staffs Lucroy had to work with in Milwaukee. That may be true, but BP’s stats are designed to apportion the proper credit or debit for each call to catcher, pitcher, and umpire alike. If BP is undercounting the command and control problems that Andrew Cashner, Martín Pérez, and multiple Rangers relievers have had, it hasn’t seemed to affect backup catcher Robinson Chirinos, who’s posted his best big league framing stats this year.

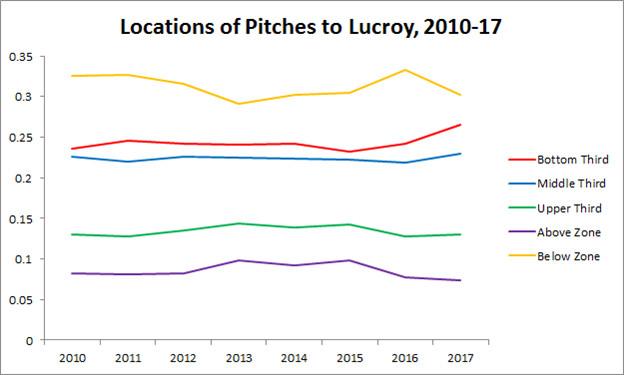

Nor can we blame a change in the strike zone for Lucroy’s recent struggles. Some evidence suggests that tall catchers tend to get the greatest rates of extra strikes up in the zone, while shorter catchers tend to do their best work with low pitches. In his heyday, Lucroy was a master of the low strike, which has become more prevalent in the big leagues over the last several years as the zone has expanded downward. It’s possible that the strike zone’s growth in that direction has hurt Lucroy in the long run by making it easier for other catchers to eke out calls that only he could consistently get during his 2010–12 peak. But that wouldn’t explain his lost strikes this season, since the zone’s lower bounds haven’t budged since their slight contraction last year, according to data from researcher Jon Roegele.

Lastly, Rangers pitchers haven’t had any trouble playing to Lucroy’s low-strike strengths. Only the Astros have thrown a higher percentage of pitches in the bottom third of the zone this season, and Lucroy has never before seen this high a percentage of pitches in the bottom third of the strike zone when he’s been behind the plate.

If Lucroy’s 2017 troubles haven’t arisen primarily from his pitchers’ command problems, changes to the strike zone, or the Rangers’ pitch locations, that leaves two likely culprits.

The Competition Has Improved

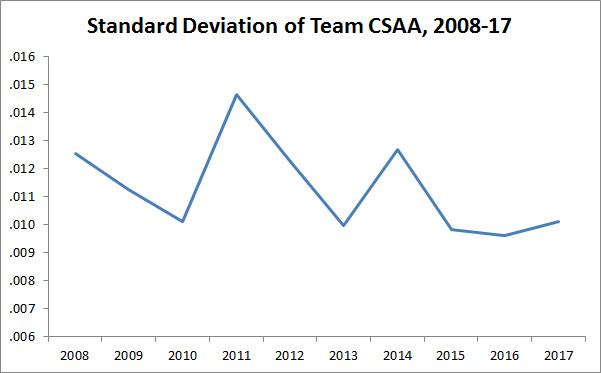

As the focus on framing in analytical circles has intensified over the last several years, the leaguewide baseline has risen, leading to less differentiation from team to team and player to player. Framing stats compare each catcher to the overall average, so Lucroy’s ratings would be lower today even if his technique were exactly the same.

The standard deviation of team CSAA — a category in which, thanks to Lucroy, the Rangers rank last this season, despite their recent success — has shrunk relative to previous years in the pitch-tracking era, indicating that teams are more tightly clustered around the average than they were in the past.

Because we can measure a catcher’s ability to expand the zone with great precision, it’s easier than ever to develop or acquire a competent catcher. The Twins were by far the worst team at earning extra strikes in the twilight years of Minnesota GM Terry Ryan’s regime, but that failing didn’t last long under the more analytically inclined Derek Falvey, who signed Jason Castro in one of his first major moves on the job. With one free-agent addition, the Twins caught up to everyone else.

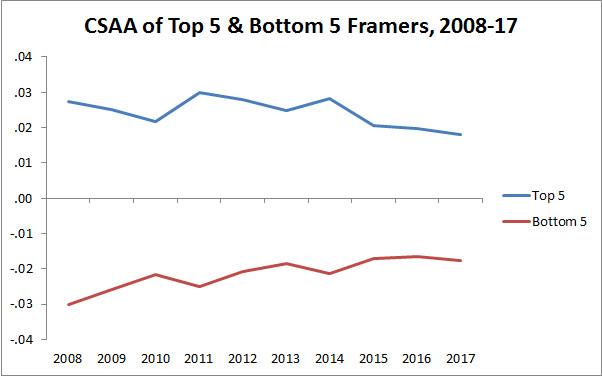

With fewer iron-gloved catchers dragging down the average, it’s harder for the best and worst receivers to stand out from the pack the way they once did. The graph below shows the average CSAA of the top five and bottom regulars (min. 4,000 pitches in full seasons and 1,200 this year) in each year of the pitch-tracking era. The range between the extremes has narrowed considerably.

If we express that in runs, the difference between the best and worst framers over a full season of 7,000 or so framing opportunities shrank from more than 96 runs in 2008 — almost 10 wins’ worth of value! — to roughly 50 runs, or five wins, in 2016. There’s a reason framing isn’t quite as sexy a sabermetric subject as it was a few years ago, and it’s not just that we’re tired of talking about it. It’s also not as significant a separator between teams and players as it was when few understood its importance even inside the game. Lucroy’s CSAA in 2012 was lower than it had been in either of his first two major league seasons, but no catcher has matched even his post-peak rate in any amount of playing time from 2015 to 2017.

Lucroy’s Skills Have Declined

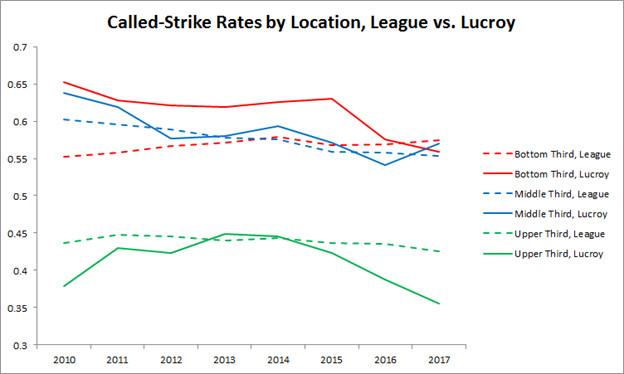

Increased competition could explain why Lucroy’s framing has fallen from its highs, but it can’t tell us why it’s now the lowest of the low. For that, we likely have to hold Lucroy accountable. The graph below shows the annual called-strike rates in each of three horizontal slices of the strike zone for both Lucroy (solid line) and the league (dashed line).

Lucroy still gets calls in the middle third of the zone at least as often as the typical catcher. But for the first time, his called-strike rate on pitches in the bottom third of the zone — which used to be his bread and butter — is lower than the league average. To make matters worse, his performance on pitches in the upper third is also at an all-time low. The more he has to move, the worse he does relative to the league.

Here’s a montage of selected called balls with 90-plus-percent called-strike probabilities caught by Lucroy this season.

Compare those clips with a montage of Lucroy receptions that I captured in 2013, when I was tracking his framing performance on a weekly basis.

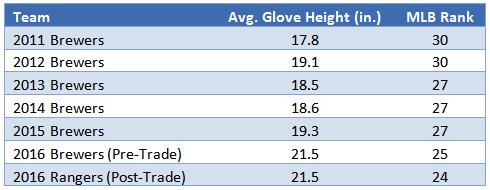

Of course, any catcher would look better in a highlight reel than a lowlight reel, but the change seems apparent. In 2013, Lucroy stayed preternaturally still: When he caught pitches, his glove would twitch toward the strike zone, but his head and body barely moved. Now, his shoulders lean, his glove shakes, and his head dips, distracting the umpire from the presentation of the pitch. Pitches even pop out of his glove with greater regularity. It’s also possible that he doesn’t crouch quite as low as he used to. Team-level COMMANDf/x data from Major League Baseball Advanced Media and SportsMEDIA Technology shows that the average catcher-glove height (at the moment of pitch release) of Lucroy’s teams during his full seasons has increased over time. (In this table, a lower rank corresponds to a lower average height.)

Maybe Lucroy’s issues are purely mechanical or mental, the product of bad habits or frustration about his slow start at the plate. But it’s probable that age and injuries have taken their toll. Lucroy suffered a fractured finger in 2011; a fractured hand in 2012; hamstring soreness in 2014 and 2015; a fractured toe in early 2015; and a concussion in late 2015. Maybe that accumulated wear and tear has made him less low, less mobile, and less steady behind the plate.

The bad news for Lucroy — and, for the rest of this season, the Rangers — is that large changes in framing performance tend to be sticky; it’s rare for a catcher to suffer a significant decline as a receiver and then bounce all the way back. In other words, the elite Lucroy, and even the average Lucroy, may be gone for good. At least we’ve got those GIFs.

Thanks to Jon Roegele, Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus, and Graham Goldbeck of Sportvision for research assistance.