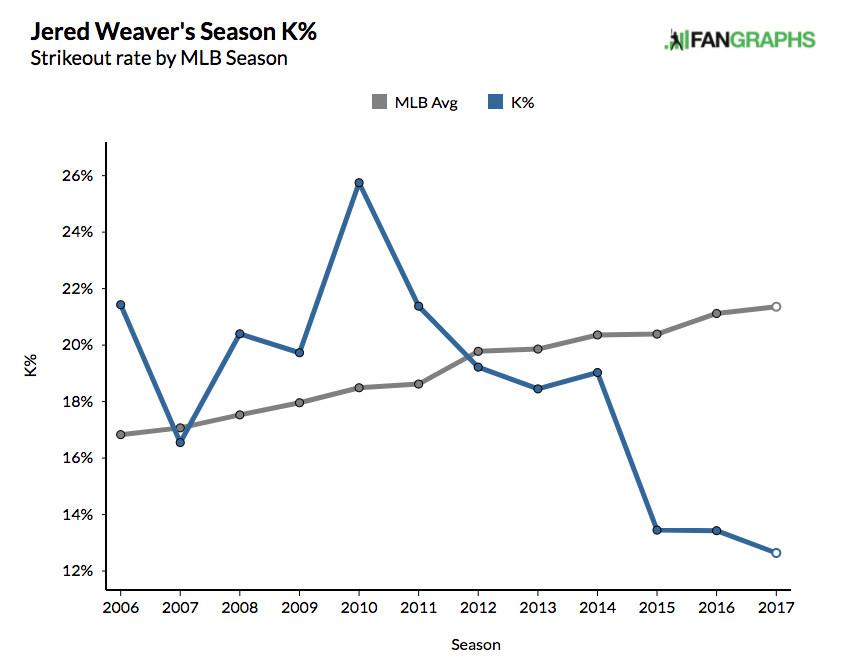

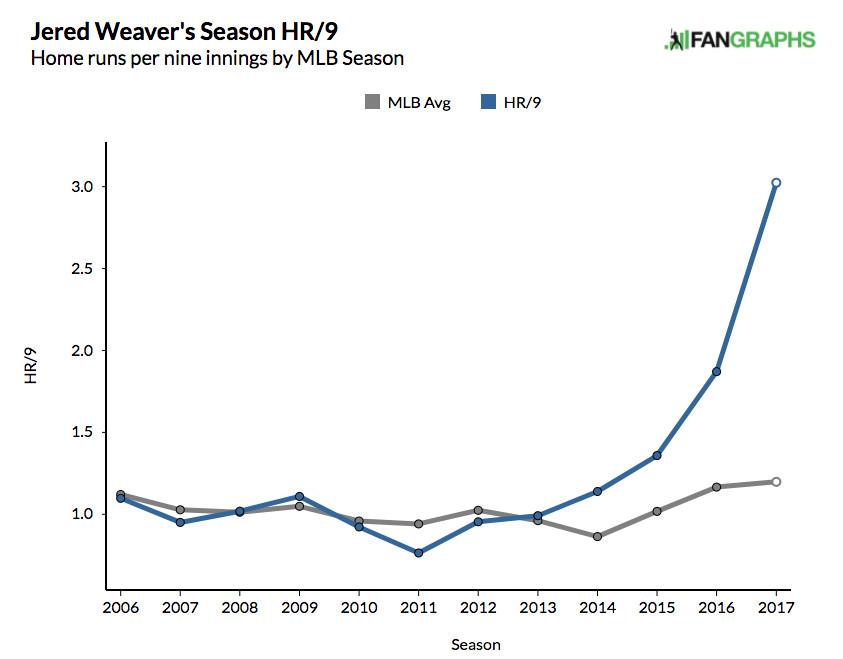

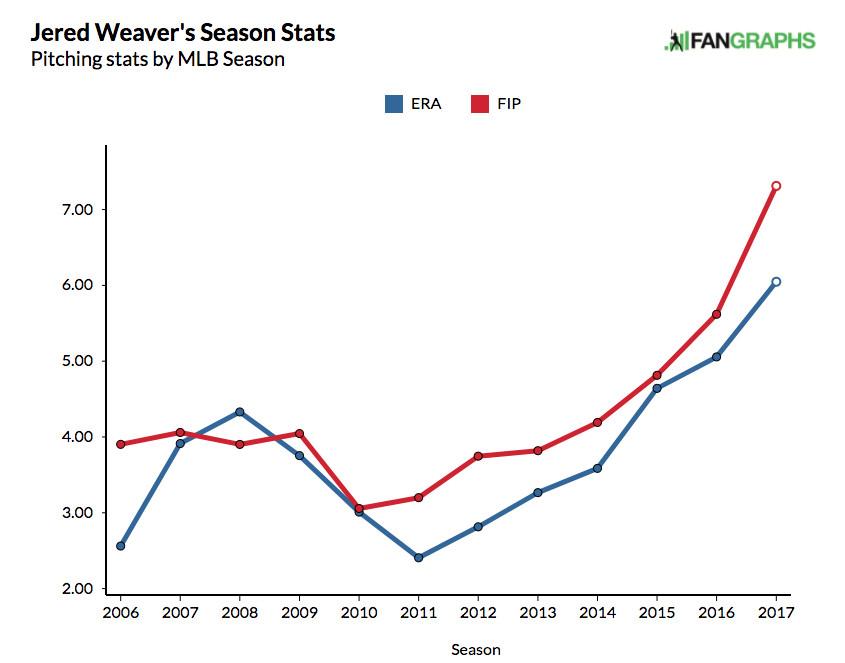

Jered Weaver is somewhat of a laughingstock in baseball circles these days. Once an All-Star pitcher with the Angels, he has experienced an unceasing decline since 2011. He’s bucked the league-wide trend of a rising strikeout rate with a depressed one of his own; his home run rate, meanwhile, has ballooned to the point of absurdity and his runs allowed have followed suit by climbing ever north. In February, the free agent left his longtime Anaheim home for San Diego, but even for a Padres team enacting a brazen, experimental tanking strategy, his performance thus far has been too brutal to bear: San Diego is 0–8 in games he has started as Weaver’s troubling trends have worsened. His HR/9 rate is more than 3, his ERA is more than 6, and his FIP is more than 7. He’d need to cut all those numbers in half to have a real chance at maintaining a stable rotation spot. Those developments look even worse, if possible, in graphical form:

Before Weaver’s last start — a six-inning, one-run outing against the White Sox that saved his job for the time being — Padres owner Ron Fowler said, “Are we going to let this continue? I think it is a short leash. We are going to have to make some decisions … We are hoping there is something left but the last several performances don’t give us much cause to be positive.” With Weaver slated to face the Diamondbacks’ potent lineup on Friday and, if he remains in the rotation long enough, the Cubs at the end of May, causes for positivity should remain scarce. And if Weaver’s fortunes don’t reverse soon, a career that became a caricature could come to an end, as a market for a negative-WAR pitcher who can’t make it on the worst team in baseball is unlikely to develop.

Jeremy Guthrie’s MLB career might have ended with a disastrous two-out, 10-run performance in a spot start in April. Weaver’s not quite at that level, but this manner of graceless exit would be no less ignominious. He was a good pitcher for almost a decade and a great one for a handful of years, and his career deserves an appreciation.

That praise begins with a brief examination of the more accomplished Weaver brother’s resume. Since 2006, when he made his MLB debut, he has thrown the eighth-most innings, tallied the 15th-most strikeouts, and recorded the 12th-most WAR among all pitchers. He has as many top-five Cy Young finishes in his career as Hall of Famers John Smoltz, Phil Niekro, and Bert Blyleven did in theirs. He threw a no-hitter — and kinda-sorta participated in another — and started an All-Star Game, led the American League in wins twice, boasts a career winning percentage north of .600, and posted a career playoff ERA of 2.60.

As much as the recent wave of young superstars has warped the sport’s conception of what a true phenom looks like, young Weaver deserved the moniker. As a junior at Long Beach State, he swept the college honors season, winning eight national player of the year awards, and after falling to no. 12 in the 2004 draft and holding out until the signing deadline due to Scott Boras–related bonus demands, Weaver reached Angel Stadium after less than a year in the minor leagues. By Baseball-Reference’s version of WAR, he then posted one of the top five seasons for a rookie starter since the 1994 strike, as he spun a 4.8-win season in just 123 innings. He also earned eternal fraternal bragging rights when the Angels designated his older brother for assignment to clear a permanent rotation spot for Jered.

He became a core contributor on the late-2000s division winners in Anaheim but posted his best years from 2010 to 2012 — when the Angels’ postseason stretch had ended — making all of his career All-Star teams and receiving all his Cy Young votes in those three seasons. In 2011, he threw the second-best season in Angel history, as measured by park- and league-adjusted ERA, and when his changeup dipped under bats and his curveball snapped into place to freeze opposing hitters, Weaver was among the most lethal arms in the majors.

He was as much a stylistic joy as he was a consistent numerical producer. A deliberate windup, during which he turned his body half toward third and cocked his long right arm back behind his head, gave way to a violent delivery as he launched the ball as a trebuchet over the plate. The contrast between his two paces — patient buildup turning to sudden motion — gave his offerings added bite and deception, allowing a pitcher whose fastball never exceeded 91 miles per hour on average to lead the majors in strikeouts one year. From 2010 to 2012, Weaver’s four-seamer was the second-most valuable in the majors, behind only Clayton Kershaw’s and ahead of peak Justin Verlander’s, which ranked third.

Even now, as Weaver’s fastball slows to the point that it wouldn’t warrant a speeding ticket — he hasn’t cracked 90 mph with a single pitch since 2014 — it generates a swing-and-miss rate that doesn’t cohere with the pitch’s component measurements. This season, his four-seamer has induced whiffs on 15 percent of swings, which places him above 36 other starters with at least 100 four-seamers thrown this year.

The surprise that stat delivers hints at Weaver’s notoriety in 2017: This version is viewed more as a foil to highlight other pitchers’ foibles rather than as a player in his own right. This year, for instance, he has a better strikeout-minus-walk percentage than Julio Teheran, Kevin Gausman, and Matt Harvey and is allowing a lower batting average than Masahiro Tanaka and recent Cy Young awardees Jake Arrieta and Rick Porcello. Those numbers reflect more on the disappointing performances of those trios of pitchers, though, than as any positive for Weaver.

We know what Weaver is at this point: a right-handed, late-career Jamie Moyer, complete with a fastball that isn’t fast and the dinger rate of a Home Run Derby soft-tosser. He’s facing an impending release from the Padres. He helps bust hitters’ slumps. He also made $99.9 million in his career, lasted in the majors for more than a decade without a rough acclimation period, and served as a prominent on-field link between Angels eras, from the annual contenders of the 2000s to the Trout-and-friends rosters of the 2010s. He now surrenders frequent homers, but Jered Weaver, former strikeout king, was once the one who soared.