Killing Us Softly

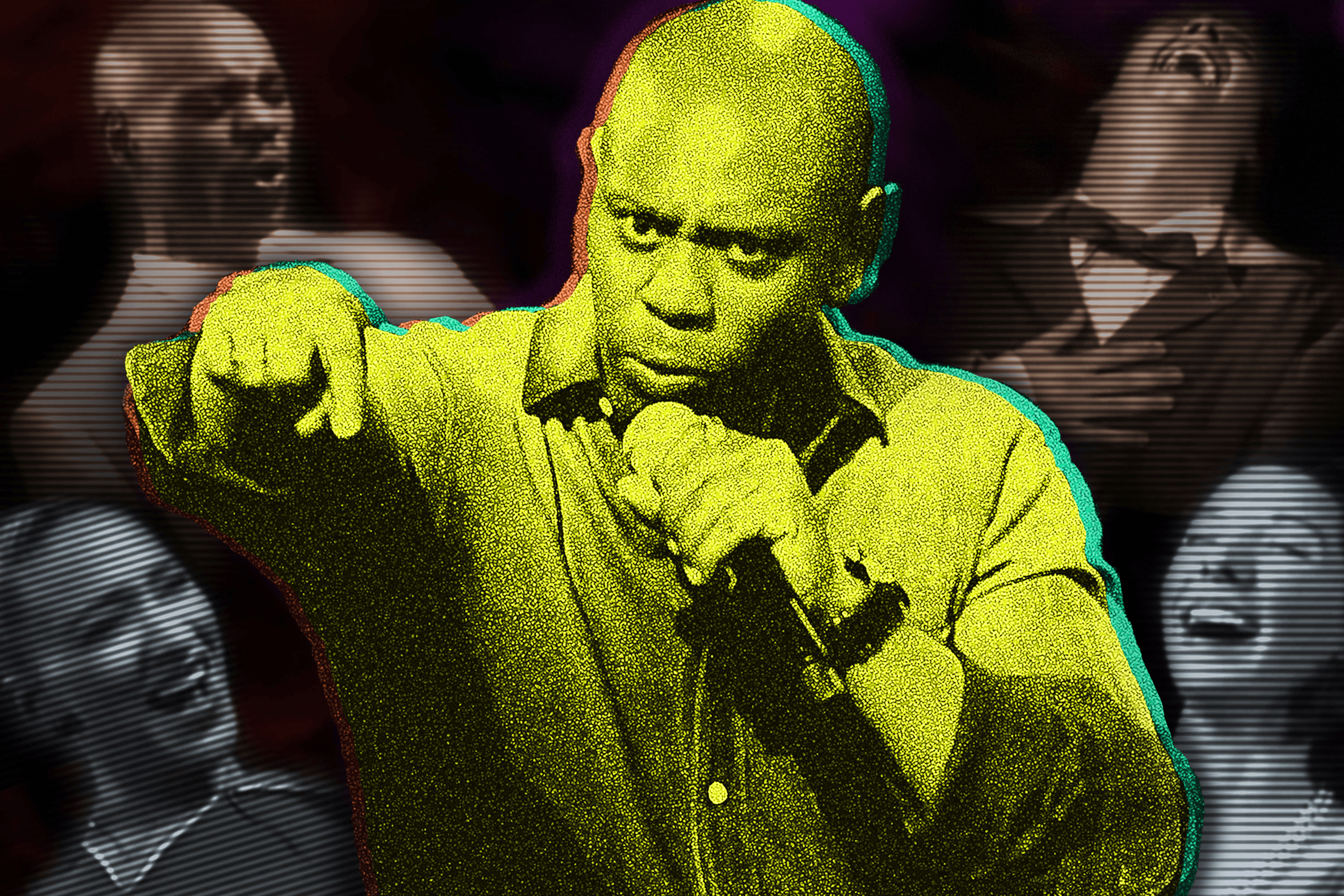

Dave Chappelle’s two comeback stand-up specials for Netflix find the legendary comedian mining a rich vein of gallows humor. Sometimes you laugh, sometimes you cry, sometimes you wince — but he always makes you think.Ten minutes into The Age of Spin, the first of two new Dave Chappelle Netflix specials streaming now (the other is Deep in the Heart of Texas), the veteran comedian settles into a personal account of the dreaded Routine Traffic Stop. It ends with him getting to drive off gingerly at 30 miles an hour on the highway — Breathalyzers don’t pick up weed, he explains — but rarely does it go so smoothly for black people not named Dave Chappelle. He goes on to talk about Marlene Pinnock, who in 2014 was beaten by a California highway patrolman on the side of a freeway, in full view of rush-hour traffic, which was, to put it simply, fucked up. Chappelle:

The morbid joke is hilarious because honestly, who thinks like that? (The answer is plenty of people; it’s just that they’re usually looking at grainy dash cam footage talking about how, if it had been them, they would’ve complied.) It’s also hilarious because of how Chappelle squawks his fight analysis with glee, which is at odds with the frankly macabre content of the joke itself.

Strip the antics, lay the facts bare, and it’s sobering, as most real things are. To be nonwhite in America is often to feel targeted and walled in. It’s difficult to explain that feeling without sounding defeatist or suicidal. The joke works because you need the laugh, more than you could’ve possibly imagined. And it’s important because of the conversations it could spark. What would we do without jokes? Despair full time, probably.

If comedy truly is tragedy plus time, then gallows humor — laughing when there’s nothing to laugh about and there’s nothing immediately better to do — tends to alchemize tragedy. Because time is ever growing short. Dave Chappelle knows the social heft of this mission; it drove him to Africa and cost him $50 million. As the story goes, he was struck on set during a racially charged skit (that’s almost all of them) by an uncomfortably jolly laugh from a white spectator. Chappelle couldn’t abide being misunderstood about topics that carry this much weight. So he went home.

And now he’s back.

Two years ago, Scottish folk singer-producer Ian McCalman gathered songs, poems, and letters from World War I into a compilation called Far Far From Ypres, and he noticed a recurring theme. While under the ever-present threat of being blown to smithereens by mortar shells, young and largely doomed men clung to fatalism and dark comedy like a life raft. Not knowing when death was coming or in what form it would arrive, soldiers had a lot of time to think about why they were being sent in scores to face it. In the absence of any real answers, they made light of it instead: “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here,” one of the songs went. It was funny, but in a blithe and detached way, buoying up just high enough above catastrophe to be able to appreciate the drollery of it.

There are earlier and more exact examples of gallows humor. There’s a particularly good one where a condemned criminal in Edo, Japan, jokes about swallowing stones to damage an executioner’s blade, and more than a few that involve actual gallows, obviously. But among my favorite examples is Patrice O’Neal’s idea of the “high-level white woman.” (It’s not especially important to note, but you should know that I can’t read the name “Natalee Holloway” anymore without mentally singing it with O’Neal’s teasing lilt.)

The late comic, who you may recognize as Pitbull from the “Playa Haters’ Ball,” had a gift for scraping away affectation and wielding unease — particularly, but not exclusively, white guilt — like a blunt instrument. At the beginning of his final special, 2011’s Elephant in the Room, O’Neal singles out a black man and his white girlfriend in the audience, and congratulates the dude on landing a “high-level white woman.” How to know she’s “high level”? How long would the authorities look for her, were she to go missing?

(This is meant to make you examine why you’re laughing at the idea of a “high-level white woman” at all.)

There’s nothing funny about the disappearance of Natalee Holloway. There’s also nothing funny about Joran van der Sloot, or his second and non-blonde-haired-blue-eyed victim, Stephany Flores Ramirez. (I had to Google this, too, by the way; none of us are as righteous or innocent as we imagine ourselves to be, and there’s humor in that too.)

What is funny is the image of O’Neal going out on the water with a white baby on a keychain. It’s a tradition in black comedy to imagine life with the figurative invincibility that white people have — the feeling that lets you end a high-speed car chase with a one-woman dance party soundtracked by Future and police sirens. On the surface, these jokes are about the absurdity of that double standard. But they’re also about why the double standard exists in the first place, and who benefits from it. Whose demonstration gets to shut down traffic without anyone being honked at or detained? Who gets to mourn what they’ve lost and who’s told to get over it? What makes pain ordinary, and what makes it worth acknowledging? Moreover, how am I supposed to give a fuck about animals when there are actual, human people being tossed into the exhaust trails of the backburner?

During that 2011 special, O’Neal satirizes a PETA commercial, and addresses the crowd while stroking an imaginary one-eyed kitten: “Hi. I’m White Lady, and I’m here to tell you that … niggas probably did it.” When he hosted Saturday Night Live last November, Chappelle recalled how Cincinnati police had said the shooting of Harambe — the rampantly eulogized gorilla that was killed to save a child who fell into his zoo enclosure — was the hardest decision the department had ever had to make: “You’re about to see a lot of niggas in gorilla suits,” he reasoned. The jokes write themselves.

The qualifying criterion of gallows humor is that the one facing the gallows actually has to tell the joke. In 2014, Chappelle’s Show cocreator and former cohost of The Champs podcast Neal Brennan got into a spicy intellectual beef — which I guess is actually just called a dialogue — with Ta-Nehisi Coates about this exact thing. Brennan propped himself up as a white man’s tour guide to black America. Coates claimed that putting a middleman between white people and black America is counterproductive, as comprehension comes from proximity to each other: “The second step is understanding that the way to get introduced to black America is to introduce yourself to black America. This is not particularly hard.”

Ideally, Brennan’s average white audience members would do the work of familiarizing themselves with blackness on their own. But in reality, Coates functionally means that everyone should speak about what they know, and please God, no more than that. That balance isn’t solely about being thoughtful, but also about being honest as it pertains to one’s perspective, and what’s shaped it. It’s what makes Brennan’s new 3 Mics special (also on Netflix) so good.

In it, Brennan switches back and forth between three microphones — one for punchy one-liners, one for traditional stand-up, and one for personal stuff about his soured relationship with his father, his clinical depression, and the unheralded ending of what he and Chappelle created together. (I should say that they’re on good terms, and have been for some time; Brennan wrote some of Chappelle’s SNL material, and Chappelle saw Brennan perform his 3 Mics set several times.)

The “personal stuff” is where it’s at. Right before his ultimate one-liner, Brennan parses why jokes are so important: “Sometimes the world can feel like a room that’s filling up with water, and for me to be able to think of a joke is like an air bubble.” Once you steal that bit of breath, the world doesn’t change, but the way you think about it does, if only for a moment. Maybe death isn’t so scary. Maybe life isn’t impossible. Maybe you do benefit from being white, typically at the expense of others. That was the tenor of Chappelle and Brennan’s love child, if you bothered to listen for it.

The “Pixies” sketch, which notionally “killed” the show, wasn’t so much about introducing the Chappelle’s Show audience to calcified racial stereotypes as it was about introducing them to themselves. In a world where facts have all but ceased to matter and there’s zero difference between good and bad things, we need more of that brazen comedy that gets us to admit to not knowing every goddamned thing.

For as much as he made us laugh, the list of Things Dave Chappelle Was Right About is strikingly long. With the passing of each salacious scandal or disposable atrocity since he left, it seems we’ve wanted to know: What would Dave think about this? Now we get the answer we’ve been ill at ease waiting for:

Chappelle’s peerless storytelling skills are on display in Age of Spin and Deep in the Heart of Texas. There’s a wonderfully crafted joke that uses the Care Bears to tease out a thinly veiled criticism of white liberalism. Recurring and occasionally problematic stories about Bill Cosby and O.J. Simpson turn out to be about the ethical compromises we make for our idols. He notes that Making a Murderer subject Steven Avery might’ve gotten off if he’d had a single black juror — because we know how police do — and also that if Avery had been black, the series would’ve just been called Duh.

As ever, he can heighten the mundane and stretch a story to the edge before snapping it back to an unpredictable punch line. The suspense lies in how he manages to land the plane. Of course, some of the things Chappelle lands on are oracular and some are … not oracular. The material is dated at times; there are moments when he kicks wide of the cultural goalposts we’ve moved since he’s been away, with some pretty indefensible stuff regarding LGBTQ issues — not all lesbians have butch haircuts, the “Q” is a safe space for those still figuring things out, not a “Sometimes Y.” That Chappelle likely means no harm doesn’t quite soften the blow. But here’s the thing: I laughed first and came to that conclusion, if shortly, afterward. And I had to think about that lag time and what it means. Others will interact with it differently — which is to say, there are gonna be some takes — but for my part, Chappelle’s willingness to splay his irresponsibility and entertain me with it, as always, demands a candid appraisal of my own blind spots.

The two specials are up there with the best of his material from Chappelle’s Show, or either of his previous two comedy hours from 14 years ago. And there’s another on the way — Texas was filmed in 2015 (remember Paula Deen?), Spin was filmed in 2016, and the third, to be released later this year, will be his first since Donald Trump took office.

What he’ll have to say about the past five or so months isn’t even remotely knowable, but I’m itching for a tale about the time he went to Mar-a-Lago and eavesdropped on an intelligence briefing.