De’Aaron Fox Would Have a Shot at Being Drafted No. 1 … If He Had a Shot

The Kentucky freshman has not shown any semblance of a jumper, and it is keeping him out of the best-overall-prospect discussion. But can it be fixed at the next level? We look at some modern precedents, and talk to a couple of shot doctors for clues.

Despite all the NBA-caliber talent around him at Kentucky, De’Aaron Fox is the engine that makes the team go. With a wiry frame at 6-foot-3 and 185 pounds with a 6-foot-6 wingspan, the Wildcats freshman has ideal height and reach for a point guard. Combine that size with über-elite athleticism and Fox is a dominant player at the college level. He gets to the rim at will, and his reach and unbelievable lateral quickness allow him to take over games on defense. He’s averaging 15.5 points on 46 percent shooting, 4.2 rebounds, 5.0 assists, and 1.4 steals a game. According to data from Hoop Lens, Kentucky scores 117 points per 100 possessions when he’s on the floor, a rate that plummets to 109 when he’s off; the Wildcats’ defensive rating climbs from allowing 93 points per 100 possessions with him to 102 without him. Fox has everything NBA teams are looking for in a point guard — except the ability to shoot.

The dazzling draft talent who can’t hit from distance has become a cliché, but even then, Fox is a special case: He is shooting an anemic 21.1 percent from 3 this season on only 57 total attempts (for the sake of comparison, fellow one-and-done point guard Dennis Smith Jr. has 55 makes on the season). Fox can’t beat opposing teams from the perimeter, but what’s worse, he’s not even trying.

“The thing that’s tough about [Fox] is that he doesn’t shoot a ton from the outside so it’s tough to get a big sample size. He’s shooting a pretty horrific percentage from 3, but his attempts are so low that he doesn’t have a chance to get into a rhythm,” said Collin Castellaw, the owner of Shot Mechanics, one of the most popular basketball instruction channels on YouTube, and a consultant for several NBA players. “I would be really interested in his confidence level, his self-talk, what the coaching staff is saying to him. He could fill it up in high school. Anyone who hit 10 3s in a high school game has some talent as a shooter.”

What happened when he got to Kentucky? Has going up against better competition revealed the holes in his game? Or has the lack of shooting around him, and the need for him to attack the lane and set up his teammates, prevented him from showing what he can do? He wouldn’t be the first player (see: Devin Booker, Eric Bledsoe) whose game was hidden by playing for John Calipari’s All-Star team. These are questions that will keep NBA executives up late at night for the next few months. Fox’s jumper is the one thing holding him back from being in the discussion with Markelle Fultz and Lonzo Ball for the no. 1 overall pick in the draft.

“Of anybody who is off the beaten path right now, he could end up as the best player in this draft,” one league executive told Reid Forgrave of Bleacher Report. “He’s the one who has the most potential to do it.”

Can a point guard survive being a bad shooter anymore?

Anytime a player with top-3 talent slips in the draft, it can be hard for teams to resist pulling the trigger.

However, the intrigue about his ceiling is matched by the concern about his floor. No prospect in this year’s lottery has a wider range of outcomes than Fox. If the jumper never comes, he will have to reinvent himself as a defensive specialist and a change-of-pace guard coming off the bench. That’s not a very appealing outcome for a lottery pick, especially in a draft as loaded as 2017. One Eastern Conference executive put it to me this way: “When you miss on a point guard in the lottery, it can set your franchise back years. Look at what happened to Orlando with [Elfrid] Payton.”

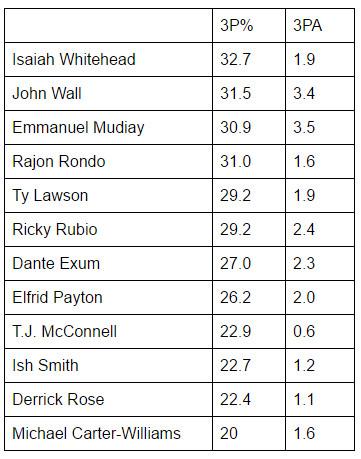

The days of nonshooters like Rajon Rondo being able to thrive at the position have come and gone. Of the point guards who have started at least 15 games in the league this season, there are only 12 who shoot less than 33 percent from 3.

Other than Wall and Exum, the other 10 guys on this list all play for below-.500 teams. The pace of change at the position is picking up: Wall is the only one guaranteed to be starting next season.

Whitehead is starting in place of the injured Jeremy Lin in Brooklyn, and the Nets could turn their entire roster over in the offseason. Mudiay has fallen out of the rotation in Denver less than two years after being drafted in the lottery, while Exum, another lottery pick, has been in and out of the lineup in Utah. Rondo, Lawson, and Carter-Williams are all on their third team in three seasons. Rubio has been in trade rumors since the day Tom Thibodeau came to Minnesota, many of them with Rose, who isn’t coming back to New York next season. Orlando may end up drafting a point guard in this year’s lottery to take Payton’s job, and McConnell may suffer the same fate in Philadelphia. Smith is a career journeyman who started for the Pistons during Reggie Jackson’s absence and who may have a shot at the job amid the chaos in Detroit.

Yet, all those guys shot better in college than Fox.

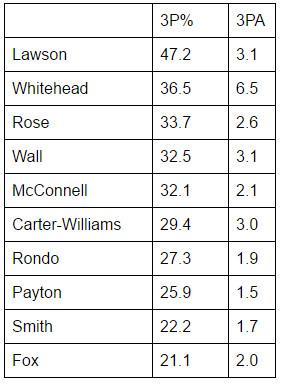

For as bad as they shoot in the NBA, the nine guys mentioned above who played college basketball all shot significantly better from 3 in their final season in school than Fox has this season. Wall is the poster child for the point guard who has succeeded in the NBA despite not being a great outside shooter, and his 3-point shooting percentage at Kentucky was one-and-a-half times higher than Fox’s.

It’s hard to be a good long-range shooter in the NBA if you weren’t a good shooter in college. Everyone points to Kawhi Leonard’s reinvention with the Spurs, going from a career 25 percent 3-point shooter at San Diego State to one of the best shooters in the league, almost overnight. However, Kawhi’s immediate improvement is the exception that proves the rule. Even players like Mike Conley and Eric Bledsoe who have significantly improved their jumpers in the NBA still shot better than 30 percent from behind the arc in their only seasons in college.

At the NBA level, the 3-point line is farther back, defenders are much longer, faster, and more experienced, and you are scouted much more heavily. If there’s a certain part of the court where a player is more comfortable, or a dead zone from which they rarely make shots, the opposing team is going to know about it. Even guys who were decent shooters in college have trouble sustaining their numbers once they get to the next level. A player who doesn’t believe in his jump shot will have that lack of trust reflected back at him by the defense. And nothing destroys an offense’s spacing like a lack of respect for the point guard’s ability to shoot.

How bad is Fox’s shot really, though?

It isn’t all doom and gloom when it comes to his jumper. Trends can tell us only so much when it comes to something as idiosyncratic as an individual shooting motion. I talked to two shooting consultants about Fox’s prospects as a perimeter weapon, and both came away pretty optimistic about Fox’s chances to improve at the next level. To give you an idea of his shooting motion, here’s a video DraftExpress made before the start of the season.

“It took me a long time of digging through the tape before I found anything. At the surface level, [Fox’s] shot looks really good. I think he’s got really good mechanics for the most part,” said Castellaw.

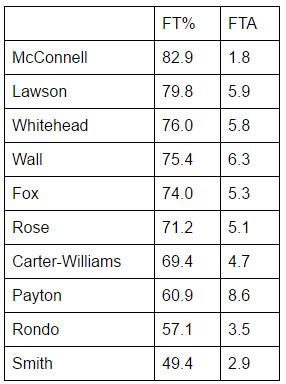

If NBA teams want some data to make them feel better about drafting Fox, they can look at his free throw shooting percentages. Free throw shooting isolates a player’s shooting technique, removing any confounding variables like the types of shots a player is taking or the way the defense is defending him. By that metric, Fox has been a better shooter than some of his fellow poor-shooting point guards were in their final season of college.

One theory circulating among front-office people is that a lack of upper body strength is holding Fox back, particularly when it comes to deeper shots. As one NBA scout told Sam Vecenie of Vice Sports, “With him, often his shot depends on how much of his legs he gets into it. If you don’t have a really strong upper body, you have to get your legs in the shot the right way. If not, you’re going to overcompensate. I think that’s what he’s doing. He’ll be helped a lot just by filling out and getting stronger.”

However, Fox’s free throw shooting numbers haven’t translated to jumpers closer to the basket than the 3-point line, either. According to the tracking numbers at Synergy Sports, Fox is in the 4th percentile of spot-up shooters around the country and in the 12th percentile of guys who shoot off the dribble.

“If you watch [Fox’s] shot slowly, instead of [releasing the ball] when his shooting arm is at a 90-degree angle, he will bring it back even further behind his head. On his 3 especially, he’s elevating too much and he’s holding on to the ball so long, which makes it much harder to have consistent arc and rhythm,” said David Nurse, a former shooting coach with the Nets who is working as a consultant with UCLA this season. “It reminds me of Norman Powell. He would jump way high and hold at the top. He fixed it by lowering his release point.” Powell, a second-round pick of the Raptors in 2015, was a career 31.4 percent shooter from 3 at UCLA and is now shooting 36.7 percent from 3 in the NBA.

Shooting a basketball is a lot like swinging a golf club. No two coaches are going to have the same philosophy when it comes to the best way to get a shot off, and the motion that works for each person is going to be somewhat different.

“It’s hard to tell without seeing him in person, but I’m curious where his eye placement is and how long he’s looking at the rim before he shoots,” said Castellaw. “That’s something the majority of poor shooters lack. The longer you can aim at your target, the more accurate you are going to be. I live in Boise, so I like to use the analogy of deer hunting. You don’t want to point the rifle at the ground and then raise up and immediately shoot at the deer.”

Just as important as the physical aspect of improving his jumper is the mental. Basketball, like any sport, is a confidence game. Shooters shoot, as the saying goes. That’s what Steph Curry told reporters after he went 0-for-11 from beyond the arc in a game against the 76ers last week: “One thing is I don’t get down on myself. Obviously, that’s why I got 11 of them up. I still have confidence the next one is going in and that will stay the same tomorrow,” Curry said.

The team that drafts Fox is going to have to invest a lot of resources in improving that aspect of the game, but investment alone isn’t enough to change a player’s jumper. If it was, Payton and Rubio would long since have become respectable 3-point shooters. “One of the most frustrating things when it comes to shooting is there’s this thought that it’s all about reps. People just want to say it’s all about hard work and locking yourself into the gym. If you don’t have your mechanics optimized, your reps are being wasted,” said Castellaw.

But, again, not everyone is Kawhi Leonard; not everyone can simply change their mechanics overnight.

“Shooting form creates muscle memory in the brain. However long you have done it one way, it takes much longer to build new habits and go the other way,” said Nurse. “I would have to learn more about [a player’s] personality before I could be comfortable saying whether a shot can be fixed. It’s more of a mindset thing.”

How many starting point guards became good shooters in the NBA?

The vast majority of shooting coaches believe that no one’s jumper is beyond fixing, which makes sense on an intuitive level. After all, no one comes out of the womb being able to shoot a basketball. However, by the time a player enters the NBA, they have been shooting a certain way for so long that it becomes difficult to fix. That’s what the data tell us, at least.

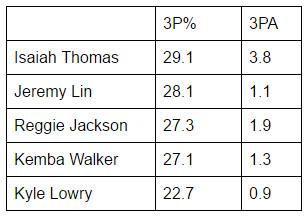

There’s only one starting point guard who overcame a poor 3-point shooting season in his final year of college to become a good long-range shooter in the NBA. That’s Kyle Lowry, who shot 8-of-18 from 3 in his sophomore season at Villanova. Lowry went from not shooting 3s in college, attempting less than one a game over the course of his career, to scorching the nets at an eye-popping 41.7 percent from 3 in 7.6 attempts per game this season. It’s an amazing turnaround that isn’t talked about enough.

Comparing Fox’s shooting as a freshman to the final college season of many NBA point guards is a bit misleading, though, since so many stayed three or four years in school. Besides Lowry, there are four others who shot less than 30 percent from 3 in their freshman seasons of college and became at least decent long-range shooters at the next level.

With the exception of Thomas, whose number of attempts as a freshman indicate his shooting issues may have stemmed more from poor shot selection than anything, time was the common factor in the improvement of the other four. Jackson and Lin didn’t break the 30 percent barrier from 3 until their junior season of college, and they are both still streaky shooters as professionals. Walker became a decent 3-point shooter by the time he left UConn, but it took him four painstaking years in the NBA, where he was the starting point guard on some of the worst teams in league history, before he became good enough for opposing teams to respect him on the perimeter. It was the same story for Lowry, who attempted less than one 3-pointer per game in his rookie season. He needed more than four years in the league before being comfortable averaging more than two 3s a game.

Even in a best-case scenario, it’s unrealistic to expect Fox to be able to turn around his shooting woes right away. The worst-case scenario is pretty grim. Fox’s 3-point percentage in his freshman season at Kentucky would be the worst mark any current starting NBA point guard had in college.

Fox’s talents as a point guard are undeniable, but everything he can do on the court can’t make up for the one thing he can’t do. It’s a binary issue: Either De’Aaron Fox learns to shoot, or he doesn’t. The fate of an entire franchise will hinge on that development, one way or the other.

Stats current as of Tuesday afternoon.