The Man Who Tamed Wolverine

Director James Mangold, like the hero of his new movie, ‘Logan,’ is a Hollywood survivor. Now he’s reinvented the superhero genre with an R-rated, post-Trump, Western-inspired bloodbath."I couldn’t get hired in Hollywood."

This is a strange thing to hear from the director James Mangold, who makes movies with the unflagging consistency of a worker bee. But it’s true.

"I’ve always been a fan of Hollywood movies. But the reality is I came up first and foremost through independent films. My first movie, [1995’s] Heavy, was a Sundance film, and my second film, Cop Land, was essentially [an] independent film for Miramax," Mangold says. "Walk the Line was passed on by every single studio in town before Fox agreed to make it. I’ve had many films that have been a struggle to get made, and you wait and you push and you push and you wait, and sometimes, [you get] Walk the Line. … But it’s hard. I try not to focus on the people saying no to me."

Somehow, Mangold has made it look easy, directing actors to Oscars (Angelina Jolie in 1999’s Girl, Interrupted; Reese Witherspoon in 2005’s Walk the Line) and career comebacks (Sylvester Stallone in 1997’s Cop Land). He’s tackled time-travel rom-coms (2001’s Kate & Leopold), Agatha Christie-esque whodunits (2003’s Identity), and Western remakes (2007’s 3:10 to Yuma). He even wrote an animated movie for Disney about a talking cat, 1988’s Oliver & Company, that doubles as a Dickens reimagining — when he was just 24 years old. His CV is varied and odd for a studio filmmaker, betraying the quirks of a roving mind — but he works at a steady clip, and produces a new picture every two or so years. Yet he rarely gets credit for the kind of fungibility that defines peers like Steven Soderbergh or Danny Boyle. Mangold has been hiding in plain sight, a craftsman bobbing and weaving his way through the machine. His new film — anticipated, brutal, R-rated, and melancholy — may change that once and for all.

Logan is the final chapter in a superhero story that explains the movie industry’s angst in this century as clearly as any. It’s a valuable piece of intellectual property about an iconoclastic and rage-filled loner, straining to transcend what makes it so popular in the first place while bound by the system that supports it. Who better to capture that than a Hollywood lifer?

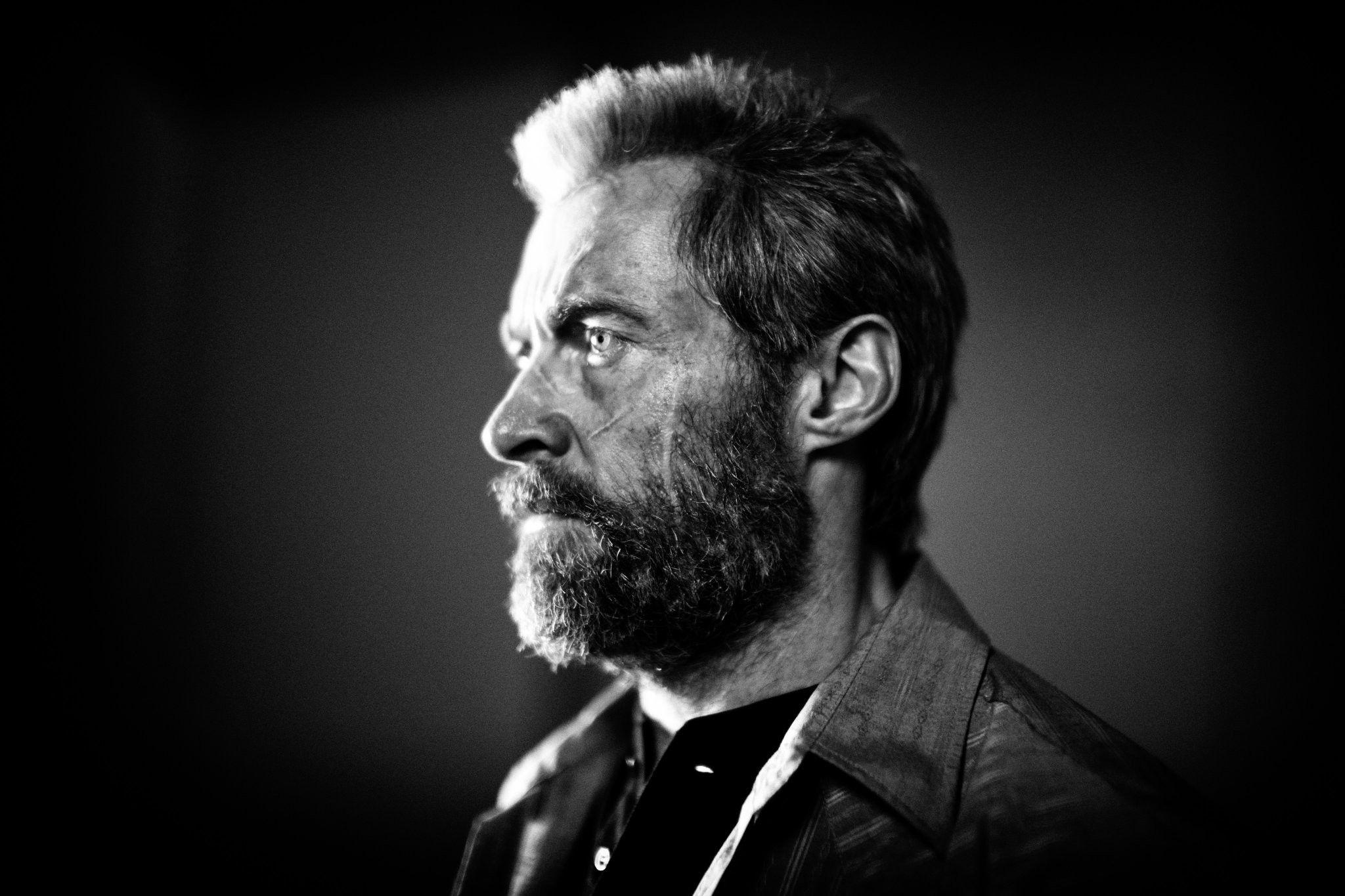

Mangold, who is 53, subverts the notions of a superhero movie, even though it’s entirely built around its biggest star, the ever game (deeply grizzled) Hugh Jackman, playing its most important character, Wolverine. The director says he’s done it the same way he has throughout his entire career.

"You’re getting people to spend millions of dollars on your vision," he says, "and whether you’re making an independent film or a studio film, the struggle remains the same for people in my position, which is: become an evangelist for your story and your work to try to get it made."

That, of course, is the trick. After many years of genre-hopping and Trojan horseplay, Logan represents the boldest gamble of Mangold’s career: selling a global entity like 20th Century Fox on a vicious, unforgiving, politically-charged vision of their billion-dollar property. That should, theoretically, be difficult. Mangold says no.

"Well, it’s not like [studio executives are] just like Simpsons villains," he says. "The executives are also troubled, I think, as well as anyone might be, by the fact that these movies are costing more and more and delivering less and less. And that they’re becoming a cliché, with the stakes every time being that the world will end if we don’t stop this or that malevolent force, and that more and more heroes are involved in every film, and the effects budgets are ballooning and there’s a kind of CG arms race going on between the studios. At some point, all we did was say, ‘Can we try the less-is-more philosophy, instead of more is more?’"

Mangold makes this sound easy. It’s not. Even an unvarnished vision requires compromise.

"Part of that was getting permission to make a rated-R film from the beginning — Hugh and I made concessions in the cost of the movie right from the start," he says. "And I wrote it, along with my partners, tailoring it to pull off the movie for less money. Really building it much more on character development than on some kind of supervillain flying down from the skies or the bowels of the earth and threatening our existence."

Because of these choices, Logan is the lowest-stakes superhero movie ever made. It might also be the best.

Mangold is a product of artistic roots. He has been surrounded by creative ingenuity throughout his life. His parents, Robert Mangold and Sylvia Plimack Mangold, are accomplished painters. His mother’s work favors haze-like visions of nature — shaded landscapes, day-break vistas, and dying trees. His father is an Ellsworth Kellyesque minimalist whose geometric work focuses on primary colors and the illusions of texture. Taken together, you can make out the influence in Mangold’s movies: the rigor and the expanse in equal measure.

"They’re still around, still painting," Mangold says of his parents. "I kind of thought they had figured life out. Making a living going into an old barn and painting all day seems like a hell of a lot of fun. The only thing I thought they were missing out on, that I somehow wanted, was it seemed very solitary."

Directors are often portrayed as mad scientists cooking up a potion that captures the imagination, but more often they are organizers and leaders. People who can effectively communicate their vision and marshal a squad. Mangold, who speaks directly and with a clarity that would be effective being barked across a massive set, has figured out how to work within and without the system.

"I love performing and the act of working together and collaborating, and that was kind of the one rebellion, was not wanting to spend [time] if not in an old barn, in some kind of solitary confinement," he says. "But nonetheless, the act of working with people and evangelizing an idea and moving it through a system is really interesting to me. I find that the more you have to do it and the more you have to defend your ideas, the sharper your ideas become."

It shows. As a filmmaker, Mangold is both an auteur and a shepherd of big-budget exercises in commerce — an increasingly unlikely combination. He’s a modern animal, too. He shoots elegant still photos on his sets, and revels in filmmaking minutiae. He tweets about scoring his projects. He shares fan art and notes obvious inspiration. He teases fanboys and the media about empty hype. All the while, his movies pursue many of the things that serious filmgoers complain have evaporated from theaters — personal stories, character development, nods at film history. Sometimes he just happens to do so with a protagonist who launches adamantium claws from his knuckles. Mangold’s origins are perhaps not so different from the character Jackman has played in nine films since 2000 (two of which, including 2013’s The Wolverine, have now been directed by Mangold). Wolverine miraculously heals with great speed, is adaptable to all environments, and seems out of time; he’s a unique delivery system for a director, and also a fitting surrogate. Mangold knows what it’s like to wander — like his mutant protagonist, he adapts and moves forward. He’s made flops, hits, and the movies that fall in that wide chasm in between. His new movie is a step forward, a not-so-subtle metaphor for the displacement many people in America are feeling.

"The X-Men films and the characters are traditionally viewed through the prism of ‘the other’ — particularly the early, and I think most successful and most personal, ones were an exploration of a kind of bigotry against mutants that could also be viewed through a prism of [race and sexuality]," he says. "In this particular movie, it seemed to me, at the moment I was even working on the story two years ago, that the issues of borders and identity and refugees and people without a home seemed really interesting. Viewing our characters through that prism seemed like it could be really fruitful."

Logan is essentially one big, fight-filled, blood-splattering comment on the refugee crisis that has been amplified by the policymaking of Donald Trump’s administration. In the movie, which takes place in a sort of X-Men universe meta-future loosely inspired by the Old Man Logan comics series, Logan transports an aging and weakened Professor X (Patrick Stewart, agog and exceptional) and a mysterious young Mexican girl known as X-23 (a glaring, tenacious Dafne Keen) to the Canadian border in an effort to outrun a militaristic force. This is heady stuff, even for the intellectually pliable X-Men characters.

"I try to remove the sense of victimization that’s built into [the] question [of] how do you get it past these evil overlords who are holding the gates closed? The fact is that: tell them the story," Mangold says. "If I went in and pitched … the ideas of borders and refugees, of course no one’s going to be interested in making the movie. But that’s not what I’m pitching them. What I’m pitching them is the story about Logan on the run with a Charles Xavier who’s got a degenerative brain disease and he’s protecting him because something horrible has happened in the past and up on their doorstep comes [this girl]. And to get her to safety, they’re going to have to travel across the United States and get across the border to Canada. That’s the story I’m pitching."

But selling that idea is not an option — it must be spring-loaded inside a more commodifiable, relatable idea. One that those not-so-evil overlords can feel connected to and inspired to pay for.

"If you ever walk into a session and start talking about the political ramifications and importance of your movie, no one responds to that because it sounds the same as a bad social studies class when you were in eighth grade — you feel like you’re being taught or preached to, and no one wants that."

He already has his supporters. "In a way it was very much the Logan film I’ve been waiting for," Chris Claremont, a foundational X-Men writer, recently said of Logan. "It was what I’d actually hoped The Wolverine should’ve been."

Mangold’s first Wolverine movie — and second collaboration with Jackman, after the decidedly different Kate & Leopold — was a mishmash of, as the director described it, "a Japanese noir picture, a Hong Kong-style crime film, with touches of samurai and swordplay." It also featured a conclusion in which Wolverine battles a giant robot controlled by a venal, evil old Japanese man. It’s deeply imperfect, which Mangold acknowledges. That movie ended with a convoluted tease that ultimately led to X-Men: Days of Future Past. Even in the standalone Wolverine movie universe, it was slave to the broader storytelling implications of the decades-spanning X-Men story. Logan is not bound by franchise obligations — it’s the opposite, a kind of era-closing denouement for Mangold and Jackman, who says he’s hanging up his claws for good. The director appears to have learned a lot having moved through the superhero machine once before. And after the massive success of Deadpool — which was released as Logan was going into production — superhero movies entered a kind of New Hollywood phase, where studios support riskier, unattached, or more unlikely versions of their precious IP.

"When you populate a film that is still going to be around 120 minutes with 10 characters, that means that each character only has 12 minutes, and that’s assuming there’s no action set piece or titles. In reality, in a lot of these movies, you end up with characters who may end up with three or four minutes of actual character work in the entire movie," Mangold says. "So it’s no wonder that people feel like they’re coming up short."

Mangold claims no strategy or philosophy for his career path.

"I’ve been very lucky. The first few films I made — and I can’t say this was something I set out to do with some kind of intellectual purpose — [were] very different kinds of movies. I feel like I’m always the same filmmaker, telling stories about the same kinds of characters, but the genre of the different films were different enough from the outside, that I was very lucky in establishing for myself early on the ability to make different kinds of movies. So there’s a lot more avenues open to me."

Many of Mangold’s movies share a common theme — outsider rebels discovering a sort of stand-in family unit. Winona Ryder in Girl, Interrupted; the shy cook Victor in Heavy; Johnny Cash and his union with June Carter; certainly Wolverine. It’s a consistency that belies the surface of his filmography, which looks like a Bingo card, dotting genres all over the place.

"Honestly, when I first started, I felt a little jealous of filmmakers who either set themselves up as the auteur voice of current independent cinema or postmodern cinema or they were the new king of horror or the new king of the Southwest or the Northeast, or whatever world they managed to offer," he says a bit wistfully. "They gave critics and fans and studios a defined box with which to brand themselves as filmmakers and a box that allowed people to understand very quickly what it is they made. But in the long run, as the world has changed and different kinds of movies go in and out, it’s like having a truck driver’s license as well as a motorcycle driver’s license as well as a car driver’s license. I feel mobile. And as the world changes, I feel like I’m able to keep skating around and finding a place to keep doing the thing I love."

"I don’t think I am roaming, I just think I’m denying — and this is said with all due respect — these obvious ways to box me in. If you just look a little deeper, I think you’ll see that these movies are much more unified — they all come from the same crazy mind, and the interest in them, from a character perspective, is very consistent."

The inspiration to keep moving, keep changing course, he says, is inspired by all his filmmaking heroes. Mangold studied in the graduate film program at Columbia University under the great Milos Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Amadeus) and with the late Alexander MacKendrick before that as an undergrad at CalArts. MacKendrick directed 1957’s classic Sweet Smell of Success, before his career took a major downturn — he’s something of a tragic figure in Hollywood history, criticized and eventually cast aside for his perfectionism and struggles to compromise. There is some irony in Mangold emerging as one of his most accomplished students.

"I learn a lot, making different kinds of movies. And my heroes, you talk about Mike Nichols or Sydney Pollack or Sidney Lumet or Howard Hawks or Michael Curtiz or I can go on and on. Billy Wilder didn’t make a comedy until his 16th movie. I’m on my 10th. And he’s known as one of the great comedic directors of all time. The reality is that the opposite is sad, which is that people get branded and boxed in and confined by the first thing they do, in a way that doesn’t allow us to grow."

"I can’t explain it, but making Kate & Leopold really helped me make Walk the Line, and making Identity really helped me make 3:10 to Yuma," he says. "Sometimes making movies of different genres really teaches you things that you could never learn if you never kind of get out of the same sandbox."