Girls thrives in confined spaces. Lena Dunham’s urban satire can struggle with long-term, cohesive stories — Hannah Horvath’s OCD manifested more like a lightning bolt than a chronic illness, and the core quartet stopped being plausible as a friend group three blow-up fights ago. The show flourishes within four walls: friends sequestered for a weekend at a seaside getaway, or lovers temporarily shut off from the world in a Brooklyn townhouse. Playing out in a single apartment and practically real time, “American Bitch” takes that compressive tendency to the extreme. The result is Girls at its most observant, funny, and melancholy on an issue that’s at once hyperspecific to New York literati and universal to young womanhood.

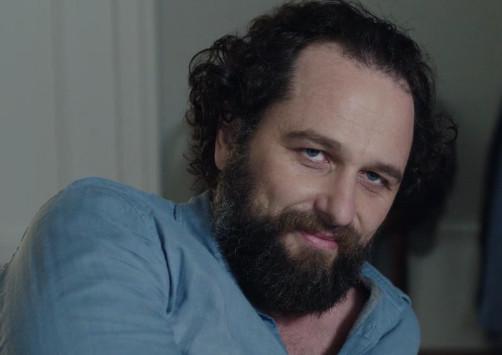

Written by Dunham herself, “American Bitch” focuses exclusively on Hannah. In the latest development of her “Modern Love”–boosted career as a freelance writer, she’s written a story on the allegations against acclaimed novelist Chuck Palmer (Matthew Rhys) on “a niche feminist website.” Palmer invites her to his palatial Central Park West apartment to offer his side of the story. The gory details of those allegations are filtered in gradually and obliquely, with words like “consensual” and “Tumblr.” The gist: murky, traumatic encounters with Palmer that start with college girls’ willing participation but don’t end that way, leaving them hurt, confused, and turning to the internet for solidarity.

For much of Chuck and Hannah’s interplay, “American Bitch” leans in Chuck’s favor. It immediately becomes clear that there’s far more connecting these insecure egomaniacs than dividing them. Hannah behaves in typically outrageous fashion: When Chuck asks, rhetorically, “How exactly does one give a nonconsensual blowjob?” she swiftly replies, “It would be very choke-y.” But Chuck takes it in stride, because for him such writerly tactlessness is like looking in a mirror. Even though the subject that’s brought them together is deadly serious, you can tell Chuck and Hannah enjoy being in the presence of kindred spirits, with Chuck’s blatant dick-swinging matching Hannah’s obnoxious arrogance beat for beat. All this plays out against a backdrop of cannily curated details: framed New York Times book reviews of volumes with names like Shannon’s Rock, tasteful art, and lest we miss the comparisons, a Woody Allen portrait and signed Philip Roth editions.

Slowly, Chuck wins Hannah over. Hannah makes valid points about the power imbalance between Chuck and eager-to-impress college girls that he refuses to see, blinded by a self-image trapped as a 25-year-old virgin on Accutane. Chuck, in part through flattery, convinces Hannah she doesn’t see the full picture and therefore isn’t qualified to write about it. He cajoles her, highlighting their similarities to build up her sympathies along with her self-esteem. (“You’re not a journalist, Hannah. You’re a fucking writer,” he tells her. We’re on the same team!) There’s an endgame here, of course, revealed when Chuck points out that if Hannah gets the renown she’s chasing, she could well end up on the other side of a similar firestorm. “You thought you knew everything, but you didn’t,” he concludes. “I didn’t,” she obediently agrees.

If their talk had ended here, “American Bitch” would be a vastly different episode. As an openly feminist 20-something entering a predominantly male space, Hannah is Dunham’s obvious surrogate, but Dunham has her own complicated history with online women’s media. With six seasons of an acclaimed television show under her belt, she is considerably closer to Chuck than Hannah professionally, and she’s been both an established figure under attack and the struggling up-and-comer attacking him. “American Bitch” could have been a score-settling lecture on the evils of the internet. But the episode doesn’t end with Hannah’s capitulation. Instead, it turns into something better, darker, and far more disturbing.

As soon as Chuck asks Hannah to lie down with him on his bed, we know what’s going to happen. By the look on Hannah’s face, she does, too. Her decision to do it anyway is so perfectly Hannah, totally of a piece with the self-destructive impulse monster we’ve known for the past six years. At least in her case, Chuck’s dubious assertion that the aspiring authors who come up to his hotel rooms mostly do it for the story proves true; so does Hannah’s sense that young women can be overwhelmed by status. That still doesn’t absolve Chuck for quite literally whipping his dick out. His smug, satisfied expression after Hannah pulls back in horror confirms one of those truisms about sexual assault that’s so hard to demonstrate: It’s not about sex, it’s about power. This close-up is going to haunt my nightmares:

The final five minutes cement the first 20 as a twisted sort of seduction. The compliments, the persuasion, the invocation of his own daughter — they’re all meant to lull Hannah into a sense of security before that final assertion of dominance. When his daughter shows up immediately afterward and Chuck slips into concerned dad mode, it’s another demonstration of a proven fact that’s nonetheless hard to hold in our minds: Predators can be parents, too, and one identity doesn’t negate the other. Thanks to the ambiguity that came before that scene, “American Bitch” doesn’t simply flip to a different flavor of polemic. Hannah is still an imperfect spokeswoman for her cause, and Chuck is still a perv who makes some valid points. By accommodating them both, “American Bitch” captures the messiness of both taking on real-life Chucks and of Girls itself, which has a long-established talent for shading sexual gray areas with black comedy.

“American Bitch” ends on an uncharacteristic note of surrealism for a show that prides itself on its unglamorous reality. As Rihanna’s “Desperado” plays, Hannah leaves the building and walks out of the shot, which stays locked onto the entrance. A crowd of attractive young women enters the frame and filters into the lobby before the screen blurs to black. We never see their faces. Hannah wasn’t the first to walk away from Chuck with a tragicomic story to tell. She won’t be the last, either.

Disclosure: HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.