Whenever a movie adaptation of a video game fails financially, creatively, or both — so, whenever someone makes a movie adaptation of a video game — we conduct a collective postmortem. “Where did the adapters go wrong?” we wonder. “Did they choose the wrong source material? Were they too faithful or unfaithful to the property they picked? Was the script too self-serious?” (Usually yes, at least for the last one.)

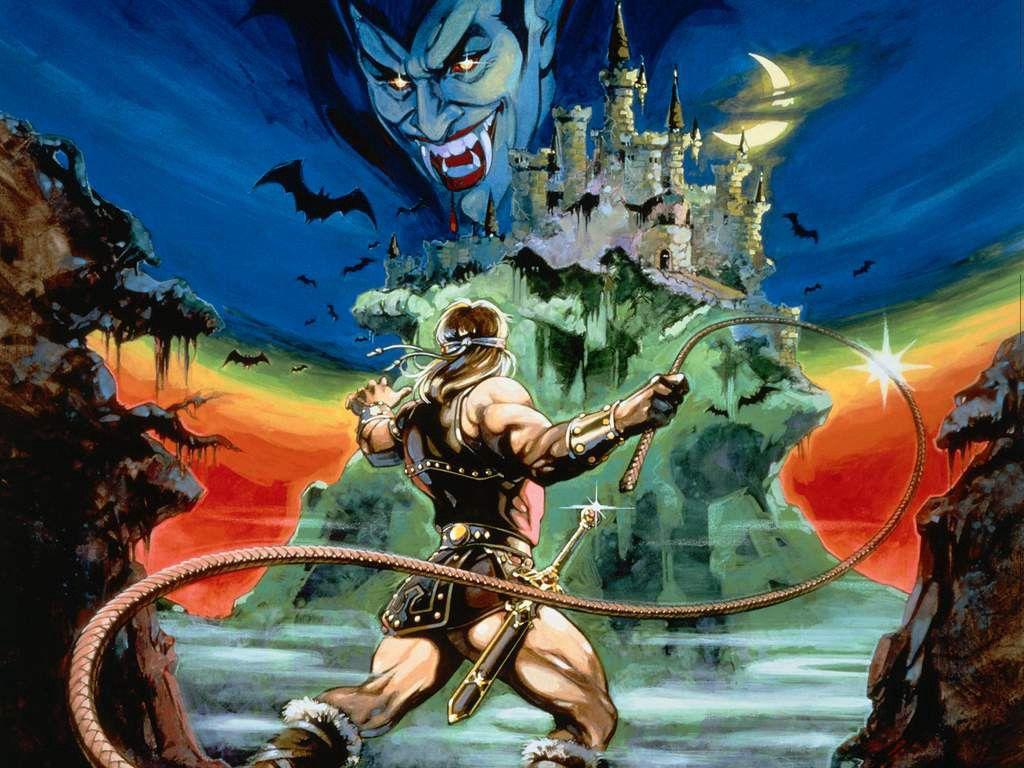

Adi Shankar, an actor and producer of films including Dredd, The Grey, and Lone Survivor, has been asking those questions a lot lately. Shankar is producing an animated Castlevania series for release on Netflix later this year, based on the Belmont Clan of video game vampire hunters who’ve battled Dracula in dozens of installments of the three-decade-old action-RPG franchise. “I personally guarantee that it will end the streak and be the western world’s first good video game adaptation,” Shankar wrote on Facebook when the news was announced this month in a brief blurb buried within a Netflix press release. The next day, he updated his forecast for Castlevania to “the best fucking videogame adaptation to date.”

When I talk to Shankar more than a week later, I ask him if he’s still sticking to his guarantee, thinking that the intervening time may have softened his stance. “I am, I am,” he says. As Shankar sees it, previous adaptations have made two main mistakes. The first is having the wrong intention: not to tell a story, but to “capture an audience without intimate knowledge of what the audience actually cares about.” Shankar says that “suits green-light stuff … based on preawareness. They’re going ‘Man, that game sold a few hundred million copies, so if we can get 1 percent of that audience, awesome.’ That’s not a creative instinct, that’s a financial instinct. So you’re already starting from the wrong place. That’s why you get The Emoji Movie, and that’s why you get the Angry Birds movie.”

The second mistake, Shankar continues, is regarding “video game movies” as a genre, rather than treating the characters as potential protagonists for a whole host of genres. He likens the misconception of a monolithic video game genre to the idea that there’s one kind of comic-book or superhero story, which we’ve seen disproved by movies as varied as Deadpool, Guardians of the Galaxy, Ant-Man, and, before long, Logan. “You can have a superhero rom-com just as you could have a superhero action thriller, just as you could have a superhero murder mystery,” he says. “Superhero movies are just not a genre in the same way that sci-fi is not a genre. … These are just motifs.”

Although Shankar won’t yet divulge details about how he plans to skirt those mistakes and make good on his guarantee, we know one way in which his adaptation attempt will separate itself from Assassin’s Creed, Prince of Persia: Sands of Time, Max Payne, and the countless creative film flops before them: It’s staying on the small screen, home court for console games. Although we’re still months away from finding out how Shankar’s Castlevania will meld the series’ trademark blend of exploration, combat, and collection, Shankar’s show has the potential to clear the short but barely blazed trail from game consoles to TV streaming apps and set-top boxes. If Castlevania succeeds, it could send a signal that a third mistake was trying to make movies in the first place.

The history of TV adaptations of video games is short and no more distinguished than the history of movies based on video games. Most earlier efforts are, like Shankar’s forthcoming Castlevania, cartoons. But unlike Castlevania, which Shankar has hinted will be “super violent” and have a “Game of Thrones vibe,” the majority were kid-friendly, Saturday-morning staples such as Super Mario World or Sonic the Hedgehog or anime-style efforts produced in Japan and sometimes exported to the States. Excluding web series, the even-less-numerous live-action offerings range from game shows (Where in Time/the World is Carmen Sandiego?, You Don’t Know Jack) to quickly canceled embarrassments (Mortal Kombat: Conquest) to programs that had little to do with the games they were ostensibly based on (Maniac Mansion). Recent years have seen few additions to the TV video game canon, although a couple of crossover efforts have made more of a mark than their troubled predecessors: Street Fighter: Assassin’s Fist, a web series, TV series, and feature film, earned praise from burned-before Street Fighter fans, and Syfy series Defiance lasted three seasons after beginning a bold experiment in simultaneous television and video game-making.

Defiance succumbed in summer 2015, leaving the TV landscape bereft of a video game presence even as the amount of TV available grew rapidly. With close to 500 scripted shows on TV networks and streaming services this year, the time seems ripe for a rash of video game transplants. Not only does TV desperately need presupplied stories, but video games are in some ways better suited to the small screens where they’ve already met success in their original forms.

One of the inherent tensions of video game movie-making is the need to compress the lore of large worlds into two hours or less, pleasing fans of the series without alienating nonplayers.

“There’s this need to say bigger is better, to say broad is better, ‘Hey, I would rather capture 100 people than 10 people,’” Shankar says. “But what the internet has shown us is that it’s better to have five people who really give a shit about what you’re doing and what you’re saying and what you’re making than have a hundred casual, passive viewers who ultimately will leave and not even remember what they watched.”

Although Shankar won’t go so far as to say he’s tailoring his series specifically to hard-core Castlevania players, he believes it’s backward to look at the most demanding fans as a liability when they’re the subset of an audience whose enthusiasm can cut through the “too much TV” static and help turn a series into a breakout success. And the larger palette of the streaming/TV medium lets creators tell a story that can placate those people without turning every nod to those in the know into transparent, patronizing fan service.

Ty Franck, the prolific coauthor of The Expanse, a sci-fi book series that’s since been adapted as an acclaimed Syfy TV series of the same name, laments the traditional tendency to turn each adaptation into “a two-hour hit list of Easter eggs for people who played rather than making an interesting story.” Franck initially conceptualized The Expanse’s mixture of military conflict and political intrigue in a future where humanity has colonized most of the solar system as the basis for a massively multiplayer online game that he envisioned as “basically sci-fi World of Warcraft.” When the MMO didn’t materialize, he turned it into a tabletop game and then the book series before Syfy came calling. Even in its current incarnation, The Expanse’s many factions and settings — or instances, as Franck originally imagined them — reveal its video game roots.

“If you try to stuff 10 hours of TV into a two-hour movie, obviously that doesn’t work,” Franck says. “And the same thing with the video game stuff. I did all the side quests the first time I played Baldur’s Gate II. It probably took me 120 hours to play the whole thing. Obviously you couldn’t tell the story that I played through in that game in a two-hour movie. Could you do a two-hour movie in the Baldur’s Gate setting? Probably. … It would not be the story that I had played, but it would be in the setting. And I think that’s the other thing, you’ve got to know what medium you’re using and what the strengths and weaknesses of the medium are, and play to its strengths.”

TV’s strength is the space and complexity to let The Expanse stay The Expanse without dramatically reducing its scope. “I think TV allows you to build worlds,” Shankar says. “Not allows you — in TV you have to build a world. It’s about characters in worlds. … [Video game] worlds are inherently interesting. Having more time to explore, you can actually populate that world more.”

In another development that’s brought video games even structurally closer to TV, games have recently become explicitly episodic, as high-profile titles such as Hitman and Telltale’s licensed adventure games (Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, Batman, and more) have been parceled out as staggered, compact, and discrete releases rather than bundled exclusively as single, stand-alone packages. But even games confined to one download, disk, or cartridge have always been at least lightly episodic, collections of quests and side quests, levels and chapters, cliff-hangers and natural, satisfying stopping points. From the beginning, TV shows and games have had the same goal: to deliver short-term contentment while enticing the spectator to come back for more. The arcade game’s “Continue?” text extends the same offer as the teaser screen that counts down on Netflix while your desire to see the next episode wars with your sedentary self-loathing.

“Video game adaptations and comic-book adaptations kind of have a similar trajectory,” Shankar says. “It’s just, video games are still in the dark ages.” Shankar sees the comic-book adaptation’s climb to dominance as a four-step process: the Blade/Spider-Man/X-Men moment, when audiences were thrilled just to see familiar spandex on screen in competently made movies; the Dark Knight/Iron Man moment, when comic-book creations proved that they could rank among the best movies of the year; the Avengers moment, when the superheroes’ cinematic universe came to full fruition; and the Daredevil moment, in which both Marvel and DC created TV ecosystems capable of catering to fans of both soapy and super-serious and demonstrated that comic-book material isn’t restricted to any single type of viewer. TV game adaptations might reach the same destination, but they can’t skip any stages. “We’ve only been at our Mario Bros. moment, so I think we have to have our Blade moment first,” Shankar says.

Although Nintendo reportedly took meetings about a live-action Legend of Zelda show and Microsoft’s Steven Spielberg–helmed Halo project for Showtime is still lingering in development limbo, it doesn’t sound as if there’s about to be a deluge of TV adaptations from the video game world. Blake Rochkind, a video game agent for United Talent Agency, says via email that he hasn’t heard much buzz about other TV adaptations of video games and that most of the action remains in the movie arena.

“TV always trails movies on this stuff,” Franck says. “So if, say, Doom had been a gigantic success at the box office, somebody would have tried to make an Unreal TV show. That’s just the way that it works, but they kept not succeeding, they kept not doing well, and so they just kept seeming like a bad risk.”

Maybe Franck is right, and TV’s video game gold rush won’t begin until after the right movie shows the world that video games are viable after the controller cord is cut. But Shankar hopes he can kick-start a movement that he might help sustain himself: Shortly after the Castlevania news, he contacted Hotline Miami creator Jonatan Söderström about adapting Söderström’s surrealist, ultraviolent shooter series too. “If Blade, Spider-Man, and X-Men had been made by Uwe Boll, we wouldn’t have The Avengers, and we wouldn’t have Legion,” Shankar says. The implication: A successful Castlevania could be the key that finally allows video game adaptations to unlock a new level on the artistic map.

As both game stories and gamers mature, it’s inevitable that adaptations will begin to break through. “We’re still shifting from the time when people who played video games were considered mouth-breathing nerds living in their mother’s basement to everybody plays video games, everybody, and they’re just as good or as bad as any other storytelling medium,” Franck says. “There’s still probably some amount of the power base on the development side who still kind of clings to that old version of what a gamer is. But it’s changing — I’m 47, and almost everybody I know my age played games of some kind. The generation that’s older than me doesn’t. The generation that’s going to follow me, they grew up in video games.”

Shankar, 32, belongs to that junior generation. “The language of video games has influenced me as much as the English language,” he says. “I’m not like a 55-year-old, 60-year-old dude who’s like, ‘Oh, what are the kids playing today?’ and then trying to find a way to profit off of that. With me you’re literally talking to someone who not just plays games, but whose core DNA, whose kaleidoscope of sounds and images that make up my life, has been shaped by video games.”

In turn, he’s trying to reshape TV, armed, like the Belmonts, with a whip he keeps cracking. “I don’t give up and I don’t quit, that’s just not in my nature,” Shankar says. “I don’t stop until things are dope.” And video games, he declares, are the “dopest artform” of all.