The Ringer’s 2017 NBA Draft Lottery Big Board, Version 4.0

A look at the 14 best prospects in the upcoming draft. This week, the focus is on the Markelle Fultz–Lonzo Ball battle, Josh Jackson’s jumper, and a new face at no. 14.

By Danny Chau, Kevin O’Connor, and Jonathan Tjarks

Welcome to The Ringer’s 2017 NBA Draft Lottery Big Board, a consensus of the top 14 prospects in the draft as determined by our three resident NBA draftniks: Jonathan Tjarks, Kevin O’Connor, and Danny Chau. Every once in a while, we’ll take a fresh look at three trending players, and, on occasion, tip you off to a deserving prospect on the outside looking in. This week, we examine the biggest flaws in our top-two prospects, revisit Josh Jackson’s jumpshot and Malik Monk’s NBA readiness, and introduce a new challenger at the no. 14 spot.

1. Markelle Fultz

Point guard, Washington, freshman (6-foot-4, 195 pounds)

(Last ranked: 1)

2. Lonzo Ball

Point guard, UCLA, freshman (6-foot-6, 190 pounds)

(Last ranked: 2)

Jonathan Tjarks: In their first meeting of the season, Ball and Fultz didn’t go at each other as much as NBA scouts would have liked. Even though Washington was a massive underdog with virtually no chance of upsetting UCLA, there was still plenty of intrigue surrounding a matchup of two of the top players in the country. There’s no better way to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of an elite prospect than watching him face another elite prospect at the same position. It’s the closest thing to watching them play in the NBA, and it doesn’t happen in many drafts. Ben Simmons and Brandon Ingram didn’t play each other last season; neither did Karl-Anthony Towns and Jahlil Okafor two years ago.

The game itself wasn’t very competitive, as UCLA got out to an early lead and never looked back, winning 107–66. More importantly, both teams spent a lot of time playing zone, and when they were in man, Ball and Fultz didn’t always guard each other. Nevertheless, watching them on the same court did reveal some interesting things about both players. These two are at the top of our Big Board for a reason, and they both looked great at times — Fultz finished with 25 points, six rebounds, and five assists, while Ball had 22 points, six rebounds, and five assists. But as we get closer to the draft lottery, it might be more constructive to take a look at each player’s most glaring issue.

Can (or will) Fultz play defense?

Fultz doesn’t have the same types of scoring issues as Ball; he’s one of the most complete offensive players to come out of the college game in a long time. The concerns for him mostly come on the other end of the floor, where he’s not nearly as locked in. Few elite players his age consistently put in great effort on defense, but his intensity in the game paled in comparison to Ball, who seemed to show much more interest in trying to win the individual matchup between the two players.

Watch Fultz closing out on this play. The scouting report on Ball is to run him off the 3-point line, but that doesn’t mean you have to be this lazy about letting him blow right past you.

Washington plays a switch-heavy scheme that gives Fultz the opportunity to showcase his defensive versatility by matching up with different types of players. However, it also means he doesn’t have to fight over screens as much, and there are many instances where he’s not communicating well with his teammates, or just completely losing track of where his man is. Fultz starts this possession guarding Aaron Holiday at the top of the key, but who is he guarding by the end of it?

Later in the same possession is a perfect example of how switching can abet laziness. Fultz is guarding Bryce Alford, who slips a back screen and gets a wide-open layup, and there’s no reason he couldn’t have followed him across the lane rather than half-heartedly calling for a switch that his teammate David Crisp doesn’t recognize is happening.

Washington scores enough to be competitive; they just don’t guard anyone. They have the 127th-rated offense in the country and the 315th-rated defense, and some (although, certainly not all) of that responsibility has to fall on Fultz. He has all the physical tools to become a better defensive player as he gets older, but having superior dimensions doesn’t automatically mean a player will become a good defender — just ask Damian Lillard. As it stands, he’s far behind guys like De’Aaron Fox and Frank Ntilikina on that side of the ball at the moment, which could develop into a bigger worry down the line. It’s something to watch with Fultz over the rest of the season, particularly when he gets a second crack at Ball and UCLA on March 1.

Can Ball score off the dribble consistently?

Of Lonzo’s seven baskets in the game, four were 3s, one was an alley-oop, and one came in transition. He scored only once when he was driving the ball in the half court. His inability to create his own shot off the dribble has been one of the biggest knocks on him all season. While taking almost all of his shots from the 3-point line and at the rim is great for his efficiency, an NBA point guard who can’t dribble into his own shot becomes pretty easy to defend.

The problem for Ball is the funky release on his shot, where he brings the ball across his body before he shoots it. Good defenders with quick reflexes are able to slap it out of his hands when he’s going up for the shot, so he needs extra space to get it off, which is why he’s so often taking step backs, even when he’s already way behind the 3-point line.

When Ball already has forward momentum, though, it’s difficult for him to stop on a dime and go into his elaborate shooting motion. He’s not comfortable taking the pull-up jumper, especially in comparison with Fultz, who makes a living raising up for the shot anywhere on the floor. Ball is such a smart player that he rarely puts himself in situations where that weakness is going to be exposed, but when he has no choice but to shoot off the dribble, it can look awkward:

Ball stumbled into a solution over the course of the game, and it could open up a lot of possibilities for him. In this sequence, in which he comes off of a ball screen, Noah Dickerson (the Washington big man) is playing back, daring him to shoot. Instead of trying a two-handed jumper, Lonzo took a one-handed floater instead, avoiding the problems with his release all together. The teardrop is one of the most effective shots in basketball, particularly for those who don’t have textbook jumpers. It didn’t look very natural coming off his hand, but that can come with time and practice.

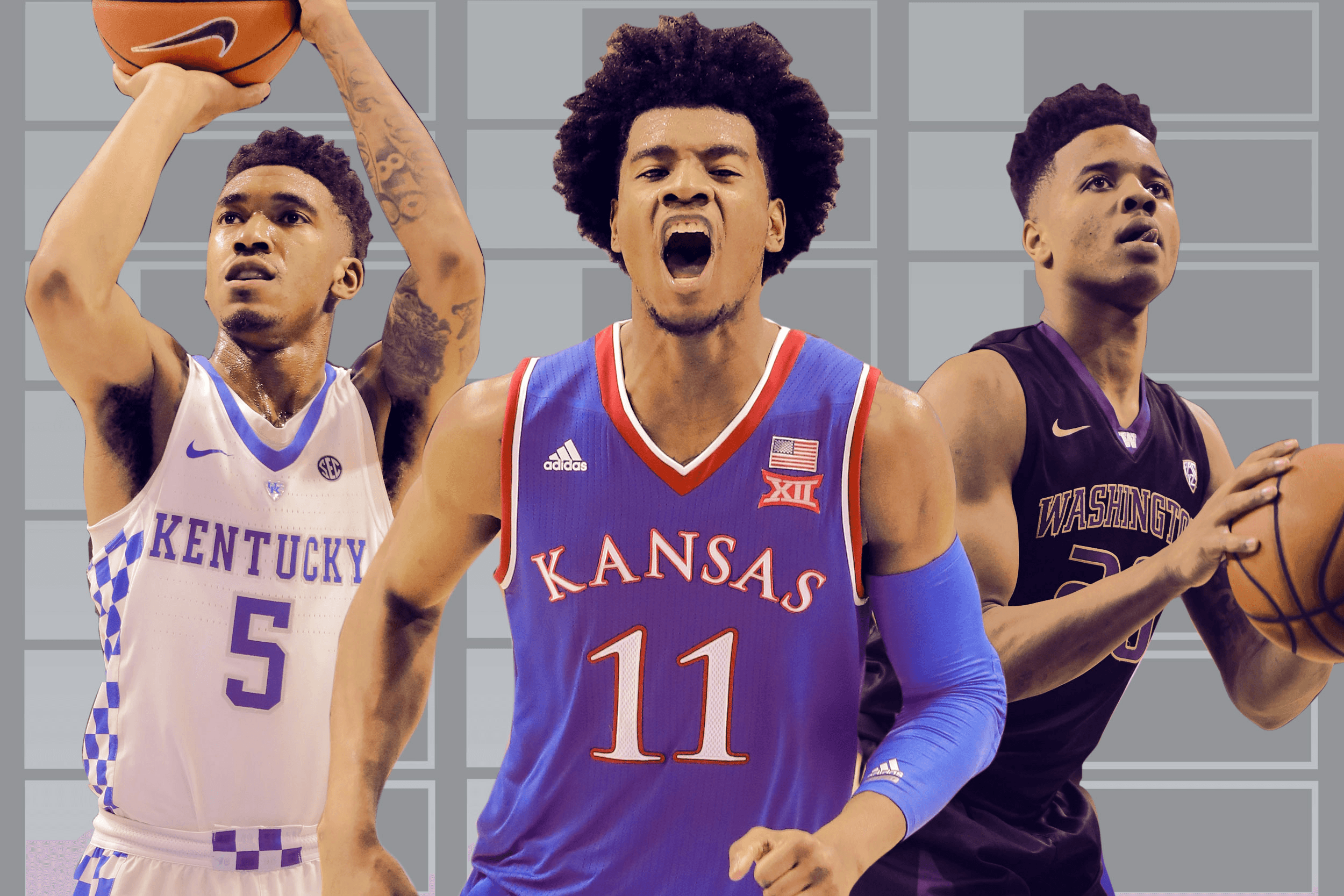

3. Josh Jackson

Forward, Kansas, freshman (6-foot-8, 207 pounds)

(Last ranked: 5)

Kevin O’Connor: Josh Jackson is The Ringer’s third-ranked player because of his tremendous playmaking ability, defensive intensity, two-way versatility, lovely afro, elite basketball IQ, and off-the-charts athleticism. Jackson looks the part of a player who fits the modern NBA style. He’s a Swiss army knife who can fill any role his team requires. He’s tough enough to battle bigger players and quick enough to swathe speedy guards. Jackson projects as a contemporary Shawn Marion.

There’s not a lot to dislike about the Kansas freshman, buuuut — oh, there’s always a but — his shaky jump shot could prevent him from reaching his potential.

Sorry. We’ve heard this story before. Aaron Gordon. Justise Winslow. Stanley Johnson. They’re the do-it-all forwards who lack a jumper. They’re the prospects who ooze potential and achieve some success, but have something that holds them back from achieving a higher level. Kawhi Leonard is one of the few outliers, and we can only hope the same fundamental changes that Leonard went through early in his NBA career happen with Jackson.

There are some who think those changes have already happened. Through 18 games, Jackson was hitting just 23.7 percent of his 38 3-point attempts; over his last six games, he’s drained 13 of 24 triples (54.2 percent). Over this stretch, Jackson is averaging 18.8 points, up from 15.1 points. On the year, the Jayhawk is now shooting 35.5 percent from 3. That’s solid, so he must be fine now, right?

I mean, look at this sharpshooter:

This streak is encouraging, but a streak is all it is. We’re dealing with a teeny-tiny sample, so it’s hard to feel confident that this is a new reality. Jackson has attempted only 62 3-pointers this season, and regardless of his level of play (high school or international), he has consistently struggled to shoot at an above-30 percent clip. It takes at least 750 shots for a 3-point percentage to regulate, per a Nylon Calculus study. Funny enough, of the aforementioned NBA players, the success stories (Leonard and Marion) shot below 30 percent from 3 in college, and the strugglers (Gordon, Winslow, and Johnson) all shot above 35 percent. Relying on college 3-point percentage is like relying on a politician to tell the truth.

You need to look at less-mainstream factors to have an inkling of future success. The first is free throw percentage, which can be a better predictor for shooting than 3-point percentage itself, according to a various studies. Free throws remove the random noise from shooting: stuff like pass placement, defender positioning, shot clock, shot type, and situation. That’s bad news for Jackson, who has struggled from the line going back to high school. At Kansas, he’s hit only 54.3 percent of his 127 free throw attempts.

The other is pure jumper form, which is harder to assess and predict since a player can always change his mechanics. That’s what happened with Leonard, but doesn’t happen with many others. Jackson’s form needs an HGTV makeover.

These are just four of his missed 3s over his hottest shooting stretch. It’s preferable when a shooter misses short or long, not left and right. If the quality of his misses changed, then we’d have a positive indicator. But his form is still a problem. We’re about to get technical here, but read each line, then reference back to the clip to observe the flaw. His feet are spread too wide, which forces his elbow to flare out. He brings the ball up to his “shot pocket” too early, which means kinetic energy from his legs doesn’t transfer to his fingers for the release. Because of a strange hitch, sometimes he ends up shooting on the way down. The whole motion is slow, which leads to heavily contested shots or even blocks by longer defenders.

His form is fixable, sure. In theory, it’s fixable for Gordon, Winslow, and Johnson, too. The shot doesn’t need to look good to be good, but if any of these guys ever become plus shooters, it’ll be because they made the right tweaks to assure a clean, consistent release — consistency is the fundamental trait shared in the best shooters. What we can’t observe is what’s going on inside — the biomechanics, the stuff that can’t be detected or measured. If that’s the problem, then his potential is limited.

Of course, Jackson doesn’t need to be Leonard (39.3 percent career from 3). He can be Jimmy Butler (34.4 percent from 3 since 2014–15). That might be enough for him to shine. It remains it be seen if he’ll even reach that level. Real or not, this recent hot streak is a wake-up call for what could be. Just watch the highlights for a glimpse of a bright future:

The player we’ve witnessed over the last three weeks is someone that deserves to be in consideration as a top pick. The question is whether he’ll evolve. Jackson is only a Charmander; we’re still looking for signs that he can become a Charizard.

4. Jonathan Isaac

Forward, Florida State, freshman (6-foot-10, 210 pounds)

(Last ranked: 5)

From Tjarks in December:

5. Lauri Markkanen

Forward/center, Arizona, freshman (7-foot, 230 pounds)

(Last ranked: 6)

From Tjarks in Version 3.0 of the Big Board:

[Stats in this section have been updated through Thursday morning.]

6. Dennis Smith Jr.

Point guard, NC State, freshman (6-foot-3, 195 pounds)

(Last ranked: 3)

From Tjarks in Version 2.0 of the Big Board:

7. Malik Monk

Guard, Kentucky, freshman (6-foot-3, 200 pounds)

(Last ranked: 7)

Danny Chau: Even for talent evaluators, Malik Monk has the ability to lull you into a sense of complacency. There is no question about his role in the NBA — he’s going to look a lot like he looks today. It’s really just a matter of scale. He probably won’t be leading his eventual NBA team in scoring, but he’ll be stalking the baseline, waiting for a chance to flare out for a 3, just as he’s done all season. He probably won’t be launching nearly eight 3s per contest as a rookie, but he will likely be leaking out on the break, even before the first signs of possession, just as he’s done all season. It’s 2017; we no longer have to pretend Monk is what he isn’t. He will fall into the athletic phylum that houses players like Lou Williams, Jamal Crawford, J.R. Smith, and Zach LaVine — he will be entrusted upon as a shotmaker, first and foremost. As he should be. He’s one of the most potent scorers in the nation, freshman or otherwise: 27.8 points per 40 minutes on 48.9 percent shooting overall and 41.6 percent from 3. He is the type of modern weapon that is coveted by all 30 teams. We know this; it’s at least a little upsetting that he seems to know this, too.

As it’s become clear that this hot streak of his is just Monk being Monk, scouts have been waiting for his next step as a dynamic scorer. His percentages from deep have not cooled, and he’s shown a complete lack of restraint in putting those shots up. Simply the idea of Monk hoisting from 3 is enough to put most college defenders on edge, and as such, his shot fake has become a reliable weapon.

Straight-line drives appeal to Monk’s rudimentary slashing ability at this point. He has the first step, and the 42-inch vertical leap to do damage around the rim, and when he actually gets there, he finishes about as well as anyone in the Wildcats’ main rotation at 76.3 percent, according to Hoop-Math. But only 20.4 percent of his shots come from that close. With wide-open space, Monk has shown the ability to throw defenders off his trail with hesitation dribbles and blow past them with his high-end speed, but in closer quarters, he silences himself. There just isn’t much creativity yet in his set of ball-handling tricks. And when he does put the ball on the floor, and his initial plan of attack is cut off, things tend not to go well:

Monk can play with a single-mindedness at times, and it manifests on both ends of the floor. He isn’t the most committed defender, and despite his tools, isn’t effective in containing the ball handler in pick-and-roll plays. Some of it is a matter of effort, some of it is a function of his role. Monk has a total rebounding percentage of 3.8, one of the lowest rates in the nation, especially for a player who averages nearly 32 minutes per game and has boundless leaping ability. To put it in perspective, former Wildcat Tyler Ulis, who essentially has the physique of a 12-year-old boy (Earl Watson’s words, not mine), posted a TRB% of at least 4.4 in both of his seasons with Kentucky. It’s hard to get rebounds when you’re constantly trying to get a step ahead on the offensive end and you’re not even in the picture when the defensive possession is finally over. It speaks to the way in which Calipari tends to compartmentalize his players’ skill sets, but also how willing Monk is to play into it all. Maybe Monk isn’t capable of more, but it would be nice for him to push his own boundaries a bit further while he’s still a Wildcat.

8. Frank Ntilikina

Point guard, Strasbourg (6-foot-5, 170 pounds)

(Last ranked: 9)

From Tjarks in February:

9. Jayson Tatum

Forward, Duke, freshman (6-foot-8, 205 pounds)

(Last ranked: 8)

From Tjarks on January 18:

10. De’Aaron Fox

Point guard, Kentucky, freshman (6-foot-3, 187 pounds)

(Last ranked: 10)

From O’Connor in Version 3.0 of the Big Board:

11. Miles Bridges

Forward, Michigan State, freshman (6-foot-7, 230 pounds)

(Last ranked: 11)

From Chau in Version 2.0 of the Big Board:

12. Justin Patton

Center, Creighton, freshman (7-foot, 230 pounds)

(Last ranked: 13)

From O’Connor in Version 2.0 of the Big Board:

[Stats in this section have been updated through Thursday morning.]

13. Robert Williams

Forward/center, Texas A&M, freshman (6-foot-9, 237 pounds)

(Last ranked: 14)

From Chau in Version 3.0 of the Big Board:

14. Zach Collins

Center, Gonzaga, freshman (7-feet, 230 pounds)

(Previously unranked)

Tjarks: If Gonzaga freshman Zach Collins wasn’t playing for the no. 1 team in the country, you would have heard a lot more about him. Collins was a McDonald’s All-American, but he has backed up Przemek Karnowski and Johnathan Williams all season. He has the talent to start, but why would Mark Few change anything when his team is undefeated? As a result, Collins is only playing 17.4 minutes per game, artificially depressing his statistics — he’s currently averaging 10.8 points, 5.9 rebounds, 0.5 assists, 0.6 steals, and 1.5 blocks per game. It’s only when you prorate his numbers to 40 minutes that you can see why people are excited about him: 24.7 points, 13.5 rebounds, 1.1 assists, 1.3 steals, and 3.3 blocks.

With a PER of 33.2, Collins has been astoundingly productive when he has been on the floor. It’s not just a matter of him dominating mid-major competition in the West Coast Conference, either. He has more than held his own in non-conference games against teams with NBA-caliber athletes like San Diego State, Arizona, Iowa State, and Tennessee.

At 7-feet tall and 230 pounds, Collins is still relatively underdeveloped and will need to add muscle to succeed in the NBA, which is normal for a 19-year-old center. He is the latest in a long line of NBA big men produced by Few, a list that includes Kelly Olynyk, Domantas Sabonis, Robert Sacre, Ronny Turiaf, and Kyle Wiltjer. Like his predecessors, he is skilled with his back to the basket, scoring 1.183 points per possession in the post, putting him in the 97th percentile of players in the country, according to the tracking numbers at Synergy Sports.

He’s also an excellent shooter, with 77.6 shooting percent from the free throw line on 4.5 attempts per game. He spends a lot of time playing in the high post, spacing the floor for Karnowski, Williams, or fellow freshman center Killian Tillie, and he’s an excellent pick-and-pop weapon with the Gonzaga guards. He’s in the 98th percentile in the two-man game, averaging an eye-popping 1.594 points per possession. While he’s only 5-of-13 from the 3-point range, he should have no problem extending the range on his shot as he gets older.

What separates him from many of his predecessors at Gonzaga is his athleticism. Don’t let his lack of muscle definition fool you. Collins can get off the ground quickly and finish in traffic:

Collins is one of the only players in the country with the length and athleticism to challenge the shot of Arizona 7-footer Lauri Markkanen. Watch how quickly he eats up space to block this:

Maybe the most impressive play from his game against Arizona in December, which was the toughest challenge Collins will face until the NCAA tournament, was a basket he gave up when he switched on to Wildcat freshman Kobi Simmons. Simmons is an NBA-caliber athlete, and Collins gets down in a stance, slides his feet, and stays right with him:

If Collins stays in school for his sophomore season and waits for his turn after Karnowski graduates, he should be a Wooden Award candidate. If he goes pro without ever being a starter, though, he would be a fascinating gamble for a team willing to take a chance on his skill, athleticism, and production in limited minutes.