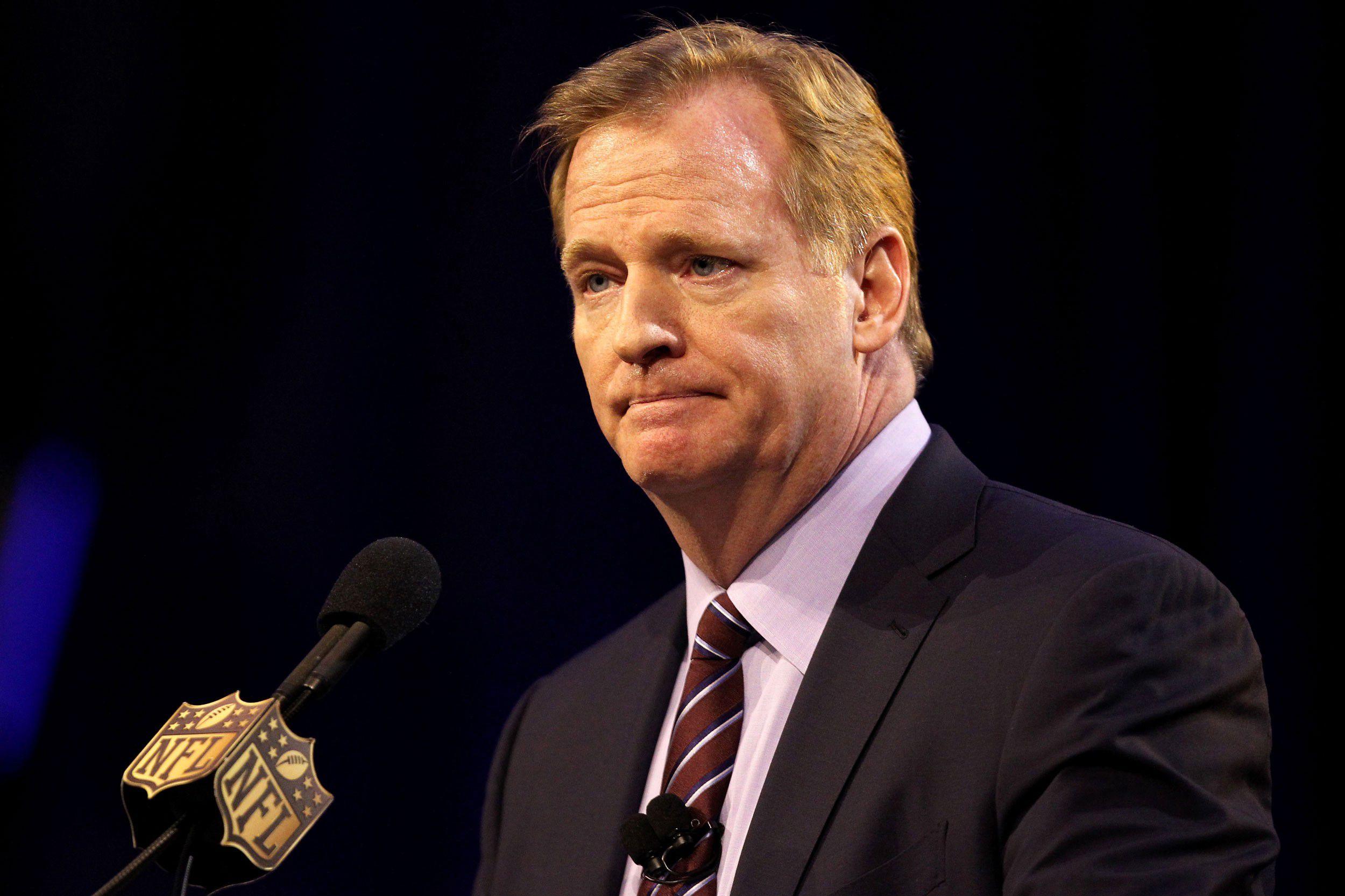

“Where’s Roger?”

Late in last Sunday’s AFC title game, with the Patriots’ 36–17 victory over the Steelers well in hand, what sounded like an entire fan base mocked the absence of Roger Goodell, who hasn’t attended a game in New England since the conference championship after the 2014 season. His campaign of perceived avoidance won’t last much longer: In just a week and change, the NFL commissioner will head to Houston for Super Bowl LI, where the Patriots will face the Falcons, and where New England’s fans will be out for blood — partly Atlanta’s, but primarily Goodell’s.

By normal human metrics, Roger Goodell is struggling. He’s deeply unpopular and on the verge of having to face down fans enraged by the aftermath of Deflategate, a painfully drawn-out investigation that ended with Goodell enforcing a four-game suspension of Tom Brady that even most neutral parties considered draconian, if not outright vindictive. He has grappled with more than a decade’s worth of scandals and made clear, time and again, that his allegiance is not to player safety or fans or most anyone’s conception of justice, but instead to the bottom line. And for this, he has been rewarded: with job security, with the enduring support of team owners, with a more than $30 million-a-year salary.

So when — not if — people boo him on Super Bowl Sunday, maybe his smile will flicker ever so briefly. Yet make no mistake: It ultimately won’t matter for the commissioner if the day turns out badly for him, because Deflategate is over — and he won. The man widely considered the most powerful person in American sports is the willing figurehead for everything that’s wrong with the NFL. And in a way, New England playing below him as he holds court in a luxury box will be just another mark of his grim success.

Goodell, who took over as the league’s commissioner in 2006, has presided over some of the uglier recent chapters in professional football, leaving his stamp emphatically on each. His term has coincided with increased understanding of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, and the effects that concussions and other forms of brain trauma have on athletes in the long term. In response, he has consistently downplayed the risks, denying a link between football and CTE until 2009, and then employing and defending people like Elliot Pellman, a doctor who spent most of his career insisting that concussions were no big deal, and squaring off against former players seeking damages in court. On other occasions, the lure of good optics was stronger, though still not strong enough to persuade him to do the right thing, as when the NFL made a show of offering money for medical research into brain trauma — up until it became evident that the findings would make the league look bad.

Or take Goodell’s attempts to litigate incidents of domestic violence in the league. The commissioner’s legacy might best be crystallized in his total mishandling of the Ray Rice case, after the former Ravens running back who was videotaped knocking out his then-fiancée in 2014. The tape remained private for months following the incident, during which time Rice was indicted on charges of third-degree aggravated assault and the NFL issued a mealy-mouthed two-game suspension and fine as Rice agreed to participate in a rehabilitation program. Nearly seven months after the incident, TMZ published video of the brutal punch — at which point the NFL backpedaled, with Goodell dubiously insisting that, somehow, the league was “never granted [the] opportunity” to see the footage, even as a law-enforcement source told the AP that the video had been passed on to the league. Goodell called the incident “ambiguous.”

When Goodell took hold of the NFL’s reins, he set about condensing the league’s power and elevating his own, much as David Stern did early in his tenure with the NBA. Goodell fashioned the commissioner’s office into a sheriff’s post, morally managing players with an uncanny propensity for issues likely to generate the most coverage. He suspended high-profile players and not always with strong justification; many of the league’s suspensions have been subsequently overturned. In 2014, the commissioner was forced to cede his ability to unilaterally issue punishments for performance-enhancing drug violations — and then, last August, wrestled the power back, using a loophole to launch investigations into James Harrison, Clay Matthews, and Julius Peppers, among others.

And then, of course, there’s Deflategate, the labor dispute that ne’er shall die. Two seasons ago, the Patriots played the Colts in the AFC title game. Late in New England’s 45–7 win, word broke that some footballs on the Patriots’ sideline might have been underinflated, theoretically making them easier for Brady to throw. The NFL launched an investigation, ultimately suspending Brady four games. Goodell upheld an initial appeal before a federal court vacated the suspension on the basis that there was next-to-no basis for such a severe punishment; the case then moved to an appellate court, where in April 2016, the suspension was reinstated. Brady missed the first four games of this fall, an entire quarter of the regular season. In his absence, New England went 3–1 behind the combined efforts of the team’s second- and third-string quarterbacks. When Brady finally came back, fans both welcomed him and treated his return as a middle finger to Goodell.

The people hate Goodell: Last February, the commissioner’s approval rating among fans dipped to 28 percent. He was booed at last year’s NFL draft, as he was at the one before it and the one before that. Take a stroll through Twitter, and you’ll quickly get a sense of the current climate.

Fans who have disagreed with his rulings have made their objections forcefully — and creatively — known. In 2013, a Mardi Gras float depicted Goodell clambering out of a tasseled pink vagina, a perhaps somewhat oblique criticism of Bountygate, or what writer David Roth called “harsh, extrajudicial and since-overturned suspensions of various former Saints.” Predictably, the question of what revenge-hungry Patriots fans have in store for the Super Bowl looms large. But those expecting much of a show will likely be disappointed.

In the months since Deflategate began, Goodell has avoided — pointedly, perhaps — traveling to Foxborough; Patriots owner Robert Kraft was considered one of his closest allies in the league prior to the controversy. And some took Goodell’s decision to attend the NFC championship game in Atlanta as a sign that he was afraid to interact with New England and its fans. But Goodell already got what he wanted. With Brady’s Deflategate suspension, the commissioner wasn’t seeking justice or a losing New England season, nor was he looking for popularity with fans. He was seeking a demonstration of absolute power, and he (and the league’s owners) received it.

Over the course of his tenure, he has considered the NFL — and his office specifically — to be an extrajudicial authority capable of enforcing its own moral code. With Deflategate, his autonomy was rewarded: The final ruling was a victory over the NFL Players Association, which in the end was unable to stop the commissioner from enacting an almost comically severe punishment for Brady and the Patriots, who had to give up first- and fourth-round draft picks and pay a $1 million fine.

There is one thing that matters to Goodell above everything else: the regard of team owners, who alone have the power to remove him from his job. And one thing matters most to those owners: that the NFL remains ludicrously profitable. Goodell has done a mighty job of that. Revenue this season is projected to surpass $13 billion, nearly double what it was in his first year as commissioner. Team values rose 19 percent from 2015 to 2016 alone. This year, the league bounced back — though not totally — from sagging ratings, in large part thanks to Goodell and Co.’s manipulation of the schedule, including flexing a playoff game due to “ice.”

Indeed, the Patriots being in the Super Bowl is almost certainly a good thing for Goodell, all but guaranteeing that the game will draw big ratings. And ironically, the interest that Goodell’s feud with the team generates may make it even more of a spectacle. And so the wheels keep turning.

In the minds of many New England fans, revenge looks like this: Brady, minutes after winning his fifth Super Bowl, beaming as Goodell — frowning, disgraced, embarrassed — hands him the Lombardi Trophy on national television, red, white, and blue confetti raining down on them both. Half of that, at least, is not all that unlikely for the three-point favorite Patriots. But if Pats fans really want to stick it to the commissioner, they’ll have to look elsewhere — organize a boycott, maybe, to go after the league’s profits, and see how deep the owners’ patience runs. Goodell is booed at nearly every public function he attends; by now, hearing a chorus of grumbles after his name is announced is probably not something that keeps him up at night.

Goodell said on Wednesday that giving the trophy to Brady would be “an honor.” That sounds like an exaggeration, but Goodell is also likely less afraid of that possibility than many hope. After all, the NFL has a tendency to memorialize oppositional and controversial commissioners beyond their milder counterparts. In a way, by becoming synonymous with football’s bleakest tendencies, Goodell has done what he set out to do all along.