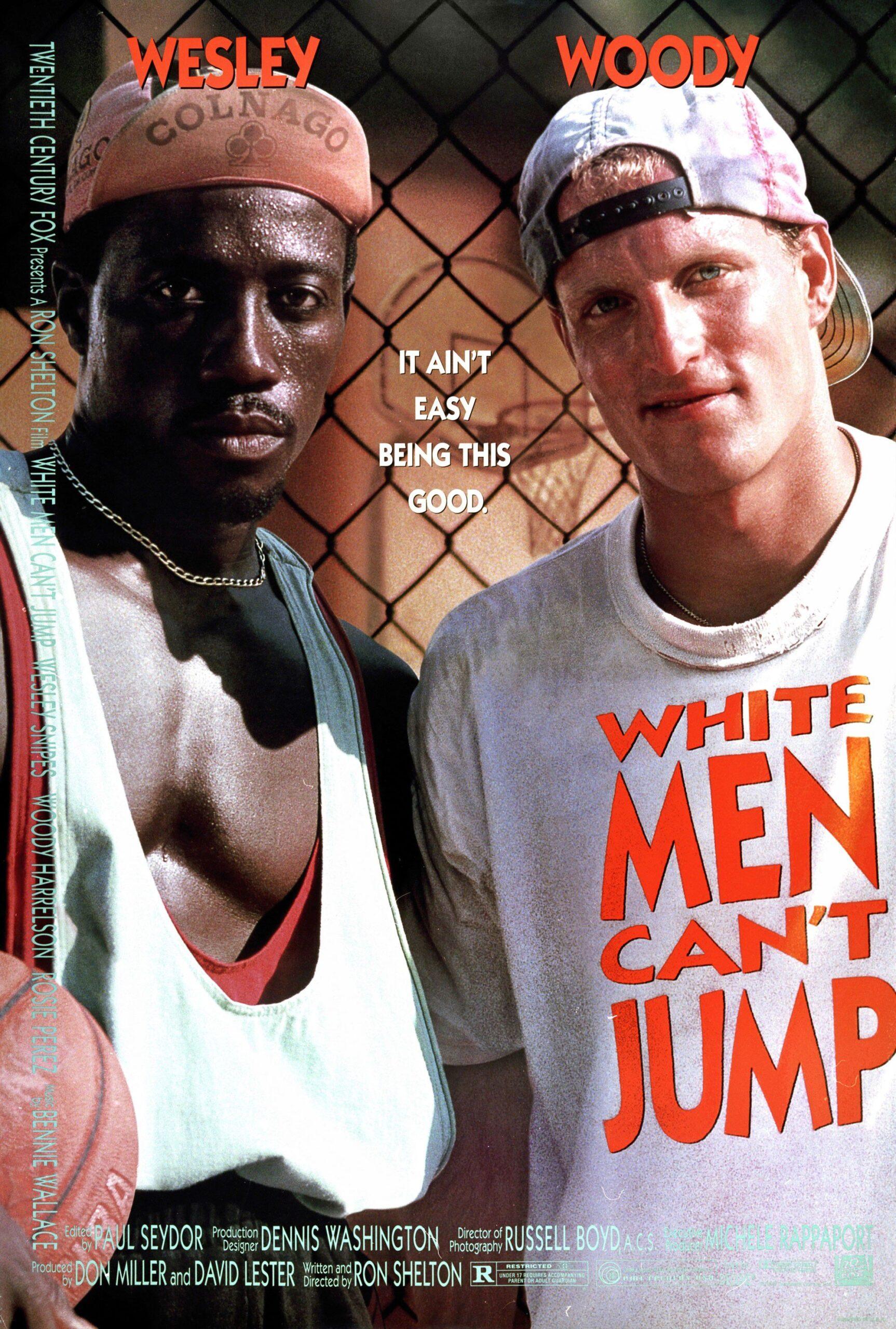

Last week, The Hollywood Reporter revealed that Mortal Media, the production company helmed by athlete-moguls Blake Griffin and Ryan Kalil, is remaking White Men Can’t Jump, the 1992 Woody Harrelson–Wesley Snipes–Rosie Perez comedy about hustling Los Angeles street ballers. Kenya Barris, the creator of ABC sitcom Black-ish, will write the new script, which will presumably borrow the broad strokes from Ron Shelton’s original.

The response on The Ringer’s #movietalk Slack channel was swift and harsh. “It’s not in the works, actually, because I won’t allow it,” said staff writer K. Austin Collins, who also added, “Kubrick already blessed the original. We don’t have to do this.” Others simply swore. “God damn it,” wrote executive editor Chris Ryan.

The Hollywood remake backlash is a staple of movie-consumer culture. Whenever a studio decides to redo a well-known movie, reaching for what looks like low-hanging fruit, fans of the original — and fans of originals, period — wonder why producers can’t be more creative and leave the classics alone. Of course, the halcyon era when every script sprang fresh from its creator’s mind is mostly a myth. The provenance of some movies is difficult to classify, with the lines between adaptations, remakes, and reboots blurred. But while it’s becoming more common for films to be part of a franchise, it’s not clear that remakes really are on the rise. It could be that each aging generation experiences an old outrage anew as the films of its youth are deemed outdated enough for a facelift. If our formative favorites are showing their age, that means we must be, too.

Many remakes are both bad and superfluous — the past several years alone brought us Ben-Hur, Point Break, Clash of the Titans, Conan the Barbarian, Footloose, and Arthur, among others — but not every remake is equally objectionable. What we need is a statistical test to determine when our reflexive, nostalgia-tinged, get-off-my-multiplex indignance is justified. To that end, I present the 10-step process for calculating Remake Necessity Score, a new rubric for determining how mad to be about remade movies.

1. How Old Is the Original?

Most remakes seem to be clustered in the 20-to-30-year-old sweet spot where the widely agreed-upon pantheon is still somewhat in flux and studios can hope to persuade the original audience to double dip (while also appealing to a new generation). There’s probably a point where age confers such standing that remaking a movie seems even more unimaginable, but in general, the older the movie, the more forgivable the urge to update it.

Scoring: Award one point for every year since the original debuted.

2. How Beloved/Respected Is the Original?

Remakes of bad or mediocre movies could correct what the originals got wrong. But the better-regarded the original is — both by both people who pay to see movies and people who are paid to see movies — the less likely it is that the remake will improve upon the first pass.

Scoring: Multiply the movie’s IMDb user rating by 10 to place it on the same scale as the Rotten Tomatoes rating. Then take the average of the two ratings, subtract it from 100, and add the result to the point total.

3. How Well Did the Original Perform at the Box Office?

If the movie made an earnings splash the first time around, it’s more likely to remain a cultural touchstone today. A remake of a massive hit might make money through name awareness alone, but it’s not really “necessary” except for the studio’s bottom line.

Scoring: Look up the original movie’s domestic gross at Box Office Mojo (or another source) and plug it into an inflation calculator to get an inflation-adjusted total in the most recent year’s dollars. If it’s less than $100 million in present-day dollars, add the difference to the point total; if it’s more, subtract the difference from the point total.

4. How Active Is the Original’s Cast?

It’s easy to identify with actors we know, and fun to return to the early work of Hollywood lifers who are still household names. But if an original movie’s main faces are forgotten, a remake with a more marketable cast makes some sense.

Scoring: Add up the IMDb credits of each of the original’s lead actors (defining “lead” however you like) in the current year and the previous two years, including only movie roles and recurring TV roles. Take the average of every lead’s score, multiply it by five, and subtract it from 50. Then add the remainder to the remake’s point total.

5. Was the Original a Foreign Film? If So, Did it Have Subtitles?

It’s downright un-American to suggest that any foreign film couldn’t be even better if we manufactured the remake right here in the US of A and made all the actors speak English, the US of A’s official language. (Note: The US of A has no official language.)

Scoring: Add 50 points for foreign films, and double that if the original also had subtitles, because text and movies don’t mix.

More seriously: The best thing a remake can accomplish, apart from enriching a profit-seeking studio, is to introduce an audience to a story it wasn’t exposed to before. Remaking a foreign film is one way to do that: After all, we wouldn’t have The Departed if not for the 2002 Hong Kong crime film Infernal Affairs. The proposed point additions stand.

6. Is the Original Reliant on Special Effects? If So, How Dated Do They Look?

Yesterday’s cutting edge can look laughable now. The more futuristic a film tries to look, the greater the risk of smirks and cringes when that future comes closer, and the bigger benefit of a remake whose technical capacity can keep pace with its ambition.

Scoring: Rate the effects’ datedness on a scale from one to five, adding 10 points for each step up the scale. Use your judgment, but for a rough calibration: Add 10 points for CGI Jabba the Hutt (either edition); 20 for The Abyss; 30 for The Last Starfighter; 40 for Logan’s Run; 50 for Kirk vs. Gorn.

7. Was the Original Filmed in Black and White?

I’m not saying it’s not glorious, but some viewers won’t watch without color. For anyone who thinks “black and white” equals “boring,” a more modern look is an easier sell.

Scoring: If the original was filmed in black and white, add 50 points to the remake’s point total.

8. Is the Original Racist, Sexist, or Distractingly Censored?

We live in a more evolved world than the one that produced plenty of unforgettable films. In some cases, the ugly parts of the old world seeped onto the celluloid, leaving uncomfortable moments for modern viewers even amid movies that are mostly unspoiled. Those moments are meaningful reminders, but you still might be tempted to keep them away from your kids. (Have them skip Sixteen Candles.)

Scoring: Add 20 points for racism, 20 points for sexism, and 10 points for Hays Code–era pants that had to stay above the belly button.

9. Will the Remake Somehow Subvert or Put a Fresh Spin on the Original?

Last week brought news of another remake: Nasty Women, a remake of 1988’s Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (which was itself a remake of 1964’s Bedtime Story). Nasty Women will gender-reverse Scoundrels, just as Mortal Media’s other in-progress movie remake, The Rocketeers, will star a black woman instead of the 1991 original’s extremely square-jawed white guy Billy Campbell. Changes like those don’t guarantee that the new movies will be worth watching, but they hint at a modicum of creativity and at least some change in story or setting, even as they further infuriate fans of the originals (if the response to 2016’s Ghostbusters is any indication).

Scoring: Add 20 points if the new cast’s makeup is dramatically different. Add 20 points if the story is set far in the future or past, relative to the original. Add 10 points if the protagonist’s geographic location or economic condition is dramatically different. (Think third-world vs. first-world more so than, say, Minneapolis vs. St. Paul.) If these details aren’t yet known, omit this category from the calculations.

10. Was the Original Inseparable From Its Era?

If the movie was inextricably tied to a specific space or era, or if its appeal at the time depended on being transgressive in a way that would seem tame today, it might suffer from the transplant to a different decade or century. Even so, some stories whose original ambiance can’t be recreated still have timeless enough arcs to survive being uprooted.

Scoring: Subtract 25 points if the original’s milieu was a core part of its appeal. Subtract another 25 points if the plot wouldn’t work as well without it.

There’s some correlation between categories — an old movie is more likely to be in black and white and feature dated special effects, an off-putting tone, and an inactive cast — but it makes sense for scores to climb quickly as the years pile up. And while some of the scoring is subjective, a remake’s necessity is inherently a matter of perspective. The calculations leave us with three broad ranges that encompass everything from last year’s releases to decades-old black-and-white bombs starring long-dead leads:

<100: The original stands the test of time too well. If everything breaks right, the remake might be good. But necessary? Nah.

100–200: A defensible (or even advisable) remake. But consider the opportunity cost: What new ground won’t you be breaking because you’re returning to old territory?

>200: What are you waiting for? The time is ripe for a remake. Give it the green light.

Now that we’ve constructed a system, only one task remains: We have to try scoring White Men Can’t Jump, the remake that inspired this exercise. Somehow, I hadn’t seen it before this week — we all have our embarrassing blind spots — so I watched it on 2017 terms, with no preexisting attachment.

1. How Old Is the Original?

Easiest answer of all: It came out 25 years ago. Add 25 points.

2. How Beloved/Respected Is the Original?

Not as beloved as it probably should be, at least according to the rudimentary metrics we’re using. The average of a 6.7 IMDb rating (times 10) and a 76 Rotten Tomatoes rating rounds to 72. Subtract that from 100, and add the remainder, 28 points.

3. How Well Did the Original Perform at the Box Office?

It did decently. White Men Can’t Jump grossed $76.3 million in the domestic market, which made it the 16th-highest-grossing movie of 1992. That amount in 1992 dollars equates to $130.4 million in 2016 dollars. We’ll round down to 130, which is 30 more than 100. Subtract 30 points.

4. How Active Is the Original’s Cast?

I’m classifying Harrelson (Billy Hoyle), Snipes (Sidney Deane), and Perez (Gloria Clemente) as the leads; Perez isn’t on the poster, but she’s the secret star. All three are still staples and well-known names, and Harrelson is getting more active with age. Snipes (three), Perez (seven), and Harrelson (12!) have accumulated a combined 22 2015–17 IMDb credits, for an average of 7 1/3 credits apiece. Multiplying by five gives us 36.7, so we’ll round up to 37. Subtract that from 50, and add the remainder, 13 points.

5. Was the Original a Foreign Film? If So, Did it Have Subtitles?

Unlike Sidney’s still-timely Trump Towers reference, the movie’s “Yo momma” jokes and exclamations of “booyah” sound semi-dated today, but no: not a foreign film; no subtitles; no points added or subtracted.

6. Is the Original Reliant on Special Effects? If So, How Dated Do They Look?

No special effects, unless you count lowering the rim so that Harrelson could dunk. No points added or subtracted.

7. Was the Original Filmed in Black and White?

The farthest thing from it. If you can think of a color, a character in White Men Can’t Jump was wearing it. No points added or subtracted.

8. Is the Original Racist, Sexist, or Distractingly Censored?

No. White Men Can’t Jump is still funny, raunchy, and real. The movie’s race relations are more nuanced than those of most of the era’s other “interracial buddy films.” Its female characters, while marginalized for much of the movie, ultimately prove to be smarter and more independent than their partners. And its innuendo and sex scenes are as explicit as those in many movies today. No points added or subtracted.

9. Will the Remake Somehow Subvert or Put a Fresh Spin on the Original?

No details yet, so too soon to say. No points added or subtracted.

10. Was the Original Inseparable From Its Era?

Difficult call. The movie’s music, fashion, and scenery scream “early ’90s L.A.,” and it benefits from its attachment to that particular time and place. There’s no way to port the same sensibility to the 2000-teens, so subtract 25 points.

On the other hand, there’s nothing in the log line that wouldn’t work today in a different setting. People still play pickup basketball, hustling schemes are still exciting, and audiences still root for likable, down-on-their luck losers. Hell, Alex Trebek is still on the air, so even the Jeopardy! plotline works.

A little arithmetic takes us to a total of 11 points, which puts White Men Can’t Jump squarely in the lowest tier of remake necessity. (For comparison’s sake, I’d give the decision to make the 2001 version of Ocean’s Eleven — not a great movie, but a smart choice of remake material — a 188.) Black-ish gets Barris the benefit of the doubt, but take it from someone who just saw the film for the first time: 25 years isn’t nearly enough time for White Men Can’t Jump to demand a reimagining. Collins was right: We don’t have to do this.