If our screens are to be believed, before the ’90s life was an assembly line that began and ended with domestic bliss. On TV, life’s two traditional, complementary, and exclusive loci were the family and the workplace. You graduated from one, disappeared into college for a bit, and emerged, fully formed, into the other. But what happens when you’re stuck between the two — when you’ve left home, but haven’t established one of your own? How do you give your life structure and meaning when you’re living in the ever-widening gray area between institutions?

The time when we answer these questions is called “emerging adulthood,” a term that could double as an alternate title for an entire generation of television shows. Friends is the most iconic example, even though Living Single got there more than a year earlier; Girlfriends and Will & Grace fit right in, while Sex and the City applied the HBO treatment with pricey locations and an impressive amount of nudity. Friendship, these shows argued, was our great and unrecognized third anchor, what kept telegenic 20- and 30-somethings afloat between formal education and marriage in otherwise overwhelming big cities. Low-stakes, amiable, and most importantly, stable: Out of watching beautiful people, well, hang out, a new sitcom blueprint was born. Contrary to the impression given by certain magazine covers, the peak of the hanging-out wave is a little-known Australian show.

Please Like Me, whose fourth season quietly made its American debut on Hulu last week, realizes the potential of the post-Friends hangout even better than its abundant stateside peers. Wunderkind creator Josh Thomas was a well-known comedian in his native Australia even before launching a critically acclaimed show at the age of 25. (Lena Dunham comparisons are natural and constant in the American press. What better way to introduce a transplant than its closest native analog?) In the States, however, Please Like Me suffered from an awkward split in distribution rights. Its initial introduction to American audiences came in 2013 via Pivot; a few months after the little-watched upstart network shuttered in 2015, three seasons’ worth of episodes appeared on Hulu without much fanfare. What might otherwise have been a predecessor to Catastrophe or Fleabag — a foreign import backed by the publicity muscle of a streaming service that could claim it as its own — instead became something of a cult object. Then again, virtually all of these shows are cult objects compared with their predecessors, in part because they have a comic, geographic, and above all cultural specificity their backlot-shot predecessors lacked.

In the 2010s, while the likes of New Girl and Big Bang Theory hold down the fort on broadcast, the model has undergone a few updates — largely on cable, television’s go-to idea lab. First, ABC’s short-lived Happy Endings blew out the premise with manically whimsical group antics, inadvertently proving broadcast wasn’t quite ready to handle that level of absurdity. Then came Girls, a show that claimed the same universalizing power as Friends in its very title, even if the pilot mocked the concept of generational voices in its opening scene. The series has had a cultural impact that far outstrips its tiny audience: Girls has become the standard bearer of the post-Friends, post-consensus hangout comedy. It has a messiness and honesty that’s sanitized out of studio audiences’ view; it also has a habit of conflating honesty with narcissism or anti-charisma. Where Girls and the wave of shows green-lit in its wake can give the impression that unlikability is a requirement for accuracy, Please Like Me moves the hangout forward without sacrificing the geniality that makes it work in the first place.

The post-Friends hangout comedy’s characters live in the shadow of the Great Recession. Older hangout shows didn’t follow their leads into the office because the office wasn’t deemed particularly interesting. Living in our brave, new, often parent-subsidized economy, post-Friends protagonists don’t have offices to go to. On Girls, Hannah Horvath’s unpaid internship gives rise to a caricature of millennial underemployment in a coffee shop. She’s not far removed from Master of None’s Dev, biding his time between acting gigs in an airy Brooklyn loft; Broad City’s Abbi, cleaning up the 1 percent’s pubes while making noises about making art; or Insecure’s Issa, losing passion for her nonprofit job while she keeps the low pay.

Josh, the hero of Australian comedy Please Like Me, fits right into this cohort. He’s clearly based on Thomas, his author and portrayer. (Same goes for Josh’s best friend, Tom, played by Thomas’s real-life best friend and collaborator, Thomas Ward.) Josh is adrift: He begins the series as a perennial student moving in with his mother, and by Season 4, he’s apparently jobless and living in a house owned by his father. It’s all captured handsomely by director Matthew Saville, who gives Please Like Me the sort of visual imprimatur common to the contemporary hangout show.

Please Like Me shares the same unassuming non-plot as most other 2010s hangout comedies, and the same credibility-straining gap between its slacker hero and successful creator. But the show distinguishes itself in its opening scene, when our sad-sack lead is broken up with by his longtime girlfriend. It’s a Judd Apatow–perfected ritual we’ve seen before, but here the self-pity is spiked before it even has a chance to take root. “I just, I kind of feel like we’ve drifted, you know?” Claire (Caitlin Stasey) ponders. “Also, you’re gay.” Our reaction is the same as Josh’s: “What?” It’s not even a coming out; it’s a pointing out. Josh’s sexuality and relationships become a focus, but their beginning is hilariously simple. Compared with the tail-devouring neuroticism of most of TV’s millennials, it’s a welcome reprieve.

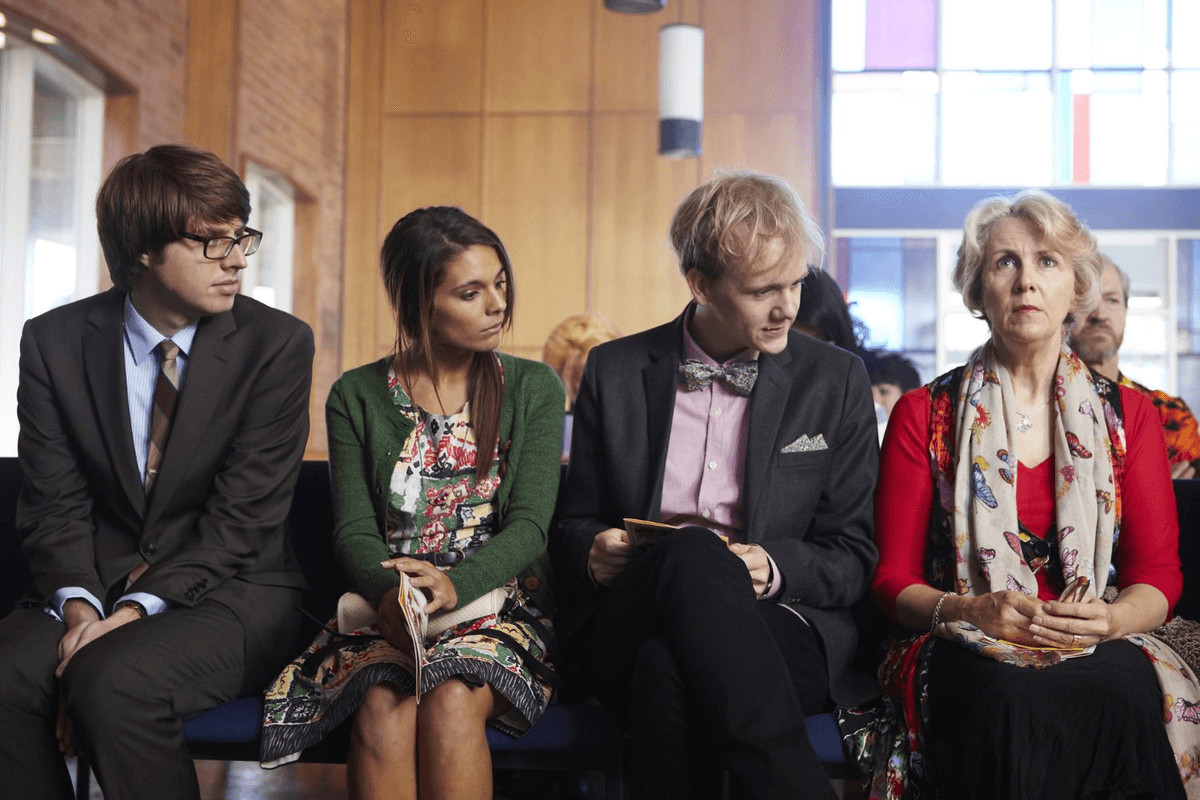

That’s Please Like Me: able to recognize that life can be both complex and a lot simpler than we pretend it is, all at once. The approach is especially welcome when it comes to mental illness, which, like queerness, is baked into the show without necessarily defining it. Josh moves in with his mother, Rose (Debra Lawrance), when she attempts suicide; when she checks into an inpatient mental hospital in Season 2 (not a crisis, just something she has to do, in matter-of-fact Please Like Me fashion), the show adds new characters in her truculent roommate, Hannah (Hannah Gadsby), and Josh’s love interest, Arnold (Keegan Joyce). Please Like Me finds the humor and banality in depression and anxiety without dismissing their impact. Remember when Hannah Horvath developed OCD seemingly out of nowhere? Arnold having an honest-to-God panic attack in the middle of a date feels like the opposite of that: a pre-established character trait manifesting in a way that’s alarming and funny, the way extreme situations sometimes are in the moment.

Please Like Me’s most distinctive improvement on the post-Friends hangout model is generational. Josh’s parents are a core part of the show, and they’re just as clueless as he is: There’s Rose, of course, and then there’s his father, Alan (David Roberts), bumbling his way through starting a family with his much-younger second wife Mae (Renee Lim). Subtly, Please Like Me maneuvers around one of the contemporary hangout comedy’s primary traps: pathologizing its subjects, or at the very least leaving them vulnerable to pathologizing by a trend-piece-hungry media. By focusing on a broad-ish cross section of a narrow demographic, hangouts are prone to readings as sociological texts. Please Like Me’s emotional range extends well into middle age: Josh’s parents have settled into more socially defined roles as parents and spouses, only to find they’re not without their own ambiguities and complications. Please Like Me is primarily about a group of 20-somethings, but it’s not a blanket statement about them.

Most of all, Please Like Me is pleasant to watch. Thomas, Ward, and their cowriter, Liz Doran, channel the natural, playfully mocking rapport of real-life best friends and family into an almost chemically affable cast. These people like each other, even though they’re aware of each other’s flaws and don’t have much of a problem pointing them out — the simplest but best explanation for what carries them through the breakups and deaths this show slowly builds the foundation to shoulder. Please Like Me has some of the most realistic optimism I’ve ever seen. It’s the perfect tone for a hangout.