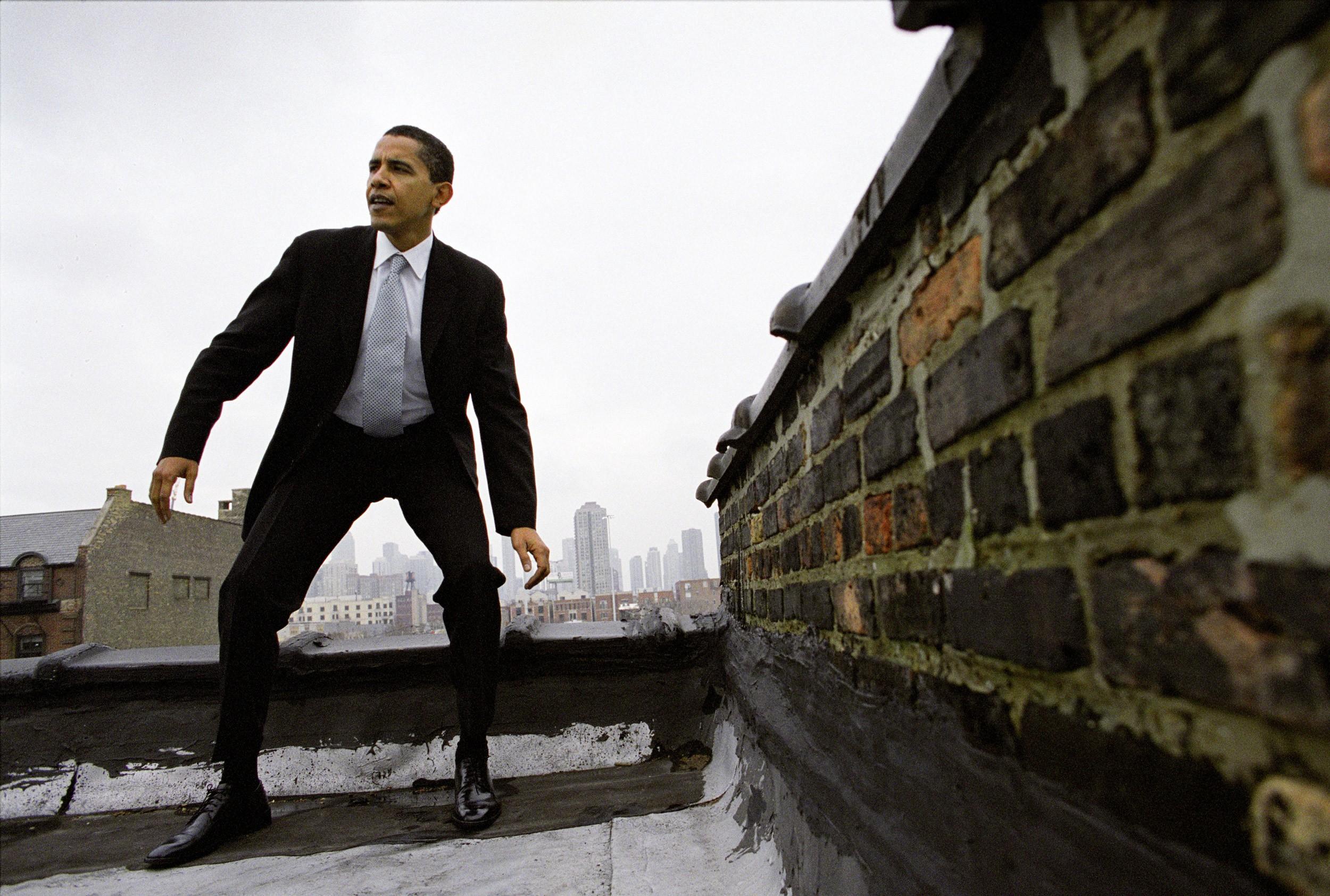

Barack Obama, Chicago’s President, Says Farewell

The outgoing POTUS confronts a complicated legacy in the city he calls home

Barack Obama spent more than 20 years, a significant portion of his adult life, in Chicago. It’s where he won his first political race, and where he lost one. It’s where his wife was raised, where he took her out for ice cream. It’s where he was a community organizer, a state senator, a U.S. senator, a law-school lecturer, a dad. It’s where things were supposed to get better after he, the first Chicago president, won. It’s where, in some ways, they got worse. It’s where, on Tuesday night, he will give his last major address as president, 10 days before he sits in front of the U.S. Capitol and watches as his successor is sworn in. It’s complicated.

I was there in Grant Park with 240,000 others on November 4, 2008. I conned an extra ticket off an acquaintance, and then another for my friend Lily, and we sat in the dust that night and waited. We were so far from the stage that when Obama finally walked out with his family to introduce himself as our president, I jumped in place and thought maybe I’d caught a flash of red in the distance: Michelle’s dress. I remember seeing video of people dancing later in the middle of 53rd Street in Hyde Park, by the Walgreen’s that filled half an aisle at the front of the store with unlicensed Obama gear: Chia pets, novelty pens, trucker hats. (I have one.) Obama could so little resist the comparison to that other iconic Illinois president that he announced his candidacy in Springfield, Illinois, the city Abraham Lincoln called home. He was sworn in with his hand on Lincoln’s Bible.

Obama became a Chicago president, or at least that’s what it seemed like. He staffed his administration that way: Rahm Emanuel, the bombastic congressman representing the North Side, as his first chief of staff; Valerie Jarrett, who got her start under Mayor Harold Washington and had ties to everything from the Chicago Stock Exchange to the Museum of Science and Industry, and David Axelrod, a fixture in Chicago politics, as advisers; Arne Duncan, the CEO of the Chicago Public Schools, as education secretary. In time, both a Daley — William, the son of one mayor and the brother of another — and a Pritzker, Penny, a Democratic fundraiser and scion of a family whose name is painted across everything from the band shell in Millennium Park to the Art Institute to the Lincoln Park Zoo. If “Chicago style” is not often used as a term of political approval, Obama was going to sand down its harsher edges and build a government that was hard-nosed and metropolitan. He came from a diverse and tricky place; he would move to another and deploy what he had learned there.

People in the city were excited. Consider this list of glowing predictions that ran in the Chicago Tribune two days after Obama’s victory. Chicago would be a shoo-in for the 2016 Olympics, to be awarded in 2009. Tourism in Chicago as well as Springfield — I say this with love, but Springfield — would surge. The White Sox would win it all again and, with a fan in the Oval Office, play a pickup game on the South Lawn.

Obama swore to visit often, telling the Tribune a month into his presidency that the South Side was going to be his Kennebunkport and that he would try to return every six to eight weeks. He eased off the pledge soon enough, the way every president has under the brunt of the responsibilities of the office, the closed-down highways and concrete barricades and Secret Service checkpoints and reinforced glass and all the general pain-in-the-ass-ness of being president, the knowing what a motorcade does to the Dan Ryan at rush hour. You can’t be from anywhere but Washington when you’re president. Donald Trump disagrees. We’ll see.

Chicago has some problems. You might have heard. The biggest, the worst, the one that boggles the mind and makes your heart hurt is the violence: In 2016, there were 762 shooting deaths there, a 19-year high. This has happened at the same time that the nation’s overall crime rate has decreased (although there has been a recent uptick in violent crime); this has happened as the president’s home sits empty and protected 24 hours a day by the Secret Service just a few miles away from the neighborhoods where some of the worst violence is concentrated. Obama tried to explain it last week, telling NBC Chicago, “It appears to be a combination of factors: the nature of gang structures or lack of structure in Chicago, the way that police are allocated in some cases, the need for more police, the easy accessibility of guns, pockets of poverty that are highly segregated.”

A lot of problems, and no magic wand hidden in the White House. Obama’s legacy has seemed more linked to the trouble there than it might otherwise, given that Emanuel left the White House to run for mayor and burdened himself with a complicated legacy of his own: Since winning he has built bike lanes and closed schools and failed to slow the carnage on the South Side and come under heavy criticism for how he’s handled police-involved shootings. This month, Emanuel laughed when he was asked if he would have become mayor without his time at the White House. “That’s a hypothetical that neither you or I can answer, OK?” he said. “I do know this: It helped.”

When 15-year-old Hadiya Pendleton was shot to death a mile north of Kenwood in 2013, just a week after marching in Obama’s second inauguration parade in Washington, the first lady went to her funeral. The president invited her parents to his State of the Union address and then went to Hyde Park Academy High School a few days later, saying that “too many of our children are being taken away from us.” When students in the bleachers called out that they loved him, Obama said, “I love you, too.” Things are still getting worse.

The outgoing commander-in-chief will build his presidential library and base his foundation there, and, when his and Michelle’s youngest daughter finishes high school in Washington, D.C., the Obamas may well return to Kenwood. People lined up this month on a 3-degree Chicago morning to get tickets to see our 44th president off. Maybe they’ll be close enough to see him. Maybe they won’t. But they’ll be there for the Chicago president to take his bow.