The Phoenix Suns knew they would have to be patient with Dragan Bender and Marquese Chriss. Bender, whom they took at no. 4 overall in last year’s draft, is the youngest active player in the NBA, having turned just 19 in November. Chriss, the no. 8 pick, is only four months older. They are younger than many of the players in this year’s freshman class, and they were drafted more on potential than any production they showed at lower levels of the sport. Bender was a role player who averaged 14.5 minutes a game for Maccabi Tel Aviv in the Israeli Premier League before coming to the NBA, while Chriss was the third option on a Washington team that missed the NCAA tournament. If they are the frontcourt of the future in Phoenix, it’s a future that is many years away.

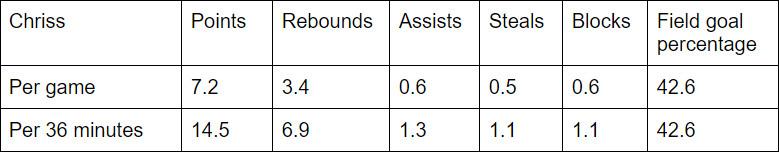

Bender and Chriss were both projected as power forwards coming into the draft, so they have been competing for playing time as rookies, but their skill sets could conceivably allow them to play together for stretches of the game, if not full time. Chriss is more physically mature than Bender, so he has been ahead of him in the rotation despite their draft order. At 6-foot-10 and 233 pounds with a 7-foot wingspan, Chriss already has an NBA-caliber physique, and he’s one of the best athletes to come into the league in recent years, with more fast-twitch athleticism in his legs than most players have in their entire bodies. He has been starting for most of the season, but he has not been particularly effective, either on a per-game or per-minute basis:

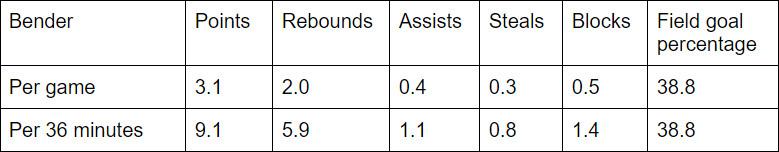

His saving grace is that Bender has been even worse, at least statistically. At 7-foot-1 and 225 pounds with a 7-foot-2 wingspan, Bender is built about as well as the average high school senior on a varsity team, stretched vertically.

The problem for both isn’t just inexperience. Bender and Chriss are big men who play like perimeter players, so they instinctively want to take bigger defenders out to the 3-point line and use the threat of their shooting ability to open up driving lanes to the basket. However, their outside jumpers are still works in progress, making them much less effective off the dribble. Bender was only a decent shooter at Tel Aviv, shooting 42.3 percent from the field, 33.8 percent from 3, and 71.9 percent from the free throw line in his final season overseas. It was the same story for Chriss, who shot 53 percent from the field, but only 35 percent from 3 (on 1.8 attempts a game), and 68.5 percent from the free throw line at Washington. Those are good shooting numbers for players their size, indicating they have the potential to become stretch big men, but there’s a big difference between having the potential to force defenders to respect them from behind the NBA 3-point line and actually doing it.

As rookies, Chriss and Bender are spending a lot of time on the perimeter, but they aren’t stretching the floor, because no one is guarding them. Chriss is shooting 31.3 percent from 3 this season, and 75 of his 80 attempts have come with no defender within 4 feet of him, according to the tracking numbers at NBA.com. It’s the same story for Bender, who is shooting 31.7 percent from 3 this season, with 61 of his 63 attempts being uncontested. The problem is particularly acute for Bender, because he’s doing almost nothing else on offense. He is allergic to the paint: 64.3 percent of his field goal attempts have come from beyond the arc, and he has taken only six free throws all season.

Not only is taking defenders off the dribble difficult when they are playing a few feet off you, it’s even more difficult when those defenders are smaller and faster than you. The days of stretch big men being able to take lumbering Goliaths out on the perimeter are just about gone, at least at power forward. Instead, NBA teams are increasingly downsizing at the position, sliding wings from the 3 to the 4. Watch what happens in this sequence when Chriss tries to take Harrison Barnes — now a full-time power forward in Dallas after playing as a small forward in Golden State — off the bounce. There’s nowhere for him to go, and he ends up dribbling the ball out of bounds:

The two best ways to attack a mismatch in size are through the post and on the offensive boards, but neither Chriss nor Bender is comfortable doing either. Of the 114 forwards who qualify for the minutes leaderboard this season, Chriss ranks 76th in total rebounds per 100 possessions, while Bender is down at 89. Almost all of the guys in their range are wings who occasionally masquerade as power forwards, exactly the types of smaller players Chriss and Bender need to be punishing on the boards to be effective. They are even worse in the post. Bender has posted up twice all season, while Chriss is scoring 0.64 points per possession in the post, in the 10th percentile of players around the league. As a result, there’s little downside to downsizing against Chriss and Bender.

That’s the problem for a lot of young power forwards. By sacrificing the power game, they have given up many of the benefits of being the bigger player, forcing them to succeed with speed and finesse. However, it’s much easier to thrive with that style when facing bigger and slower defenders, the ones who are seeing the floor less and less given the widespread abandonment of bullyball. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle.

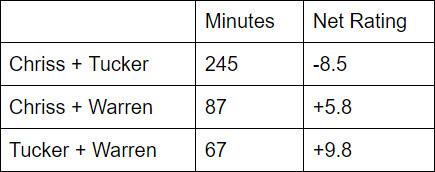

From the Suns’ perspective, if teams are downsizing against Chriss and Bender, what do they have to lose by downsizing with them and playing T.J. Warren and P.J. Tucker as power forwards? Warren isn’t a great outside shooter, either, but he’s a much more aggressive and prolific scorer; Tucker is a proven shooter and a hard-nosed defender who can clean the glass better than either of their two young big men. The numbers bear it out. The three-man combination the Suns have used the most this season is Eric Bledsoe and Devin Booker, their starting backcourt, plus Tyson Chandler, their starting center. Look at the difference in effectiveness when those three play with Warren and Tucker at the forward positions, in comparison to when Chriss plays with them and either Warren or Tucker.

Considering how the game is being played these days, the only way to get Chriss or Bender a speed mismatch is to continue downsizing and play them at center. However, there aren’t many minutes available at the position given the presence of Chandler, who’s on the second season of a four-year, $52 million contract, and Alex Len, a former lottery pick set to enter restricted free agency this summer. Even if the Suns clear the logjam at center, though, having Chriss or Bender as the biggest player on the floor presents other hurdles. No coach is going to be comfortable asking a 19-year-old rookie to anchor a defense, especially if he rebounds as poorly as they do. Both Suns rookies are terrible at defending the pick-and-roll as well: Chriss gives up 1.29 points per possession when defending the roll man, and Bender is giving up an astronomical 1.60 points per possession, albeit in a very limited sample size.

Where Bender distinguishes himself from his fellow rookie teammate is his ability to at least somewhat protect the rim. Neither blocks many shots, but Chriss is giving up an eye-poppingly bad 60.3 percent field goal rate at the rim, compared to only 50.7 percent for Bender. A lot of it comes down to court awareness. For the most part, Bender plays with his head on a swivel, tracking the movements of the other nine players on the floor and reacting to what is happening in front of him. In this sequence against the Cavs, Bender reads a back screen, calls out a switch, and then recovers to his new man when he cuts to the rim and blocks his shot:

Chriss, in contrast, can often get lost as a help-side defender, and it’s hard to tell what is going through his mind at times. It doesn’t matter how athletic you are if you jump out of the ball handler’s way instead of jumping straight up and contesting the shot at the rim:

Almost all of the advanced metrics favor Bender, although it’s tough to compare the two given that Bender has played almost half as many minutes as Chriss, most of them against reserves rather than starters. Bender just seems to have a better feel for the game, which isn’t surprising given that Chriss was a football player who didn’t start playing organized basketball until he was in high school, while Bender has been a professional in Europe since his early teen years. There’s nothing too flashy about this drive-and-kick, but Bender’s ability to probe the defense, find the open man in the corner, and start the ball moving from side to side eventually winds up creating an open 3 for himself:

The two make for a study in contrasts. The areas where Chriss struggles, particularly decision-making and court awareness, are where Bender is at his best, while Bender’s difficulties come from his inability to run, jump, and bang with the best athletes in the NBA, the strength of Chriss’s game. There are two different schools of thought when it comes to their developmental track. On one hand, Chriss is good at all of the things that no coach can teach, and he should become more refined as he spends more time in the league. On the other, Bender will become stronger as he spends more time in the weight room and his body fills out, while there have been plenty of über-athletic players who never put it all together in the NBA.

If everything goes according to plan, Chriss and Bender will complement each other really well down the line, giving the Suns a frontcourt duo that can spread the floor on offense and switch screens on defense, allowing Phoenix to play five-out basketball with two guys taller than 6-foot-10. Bender would protect the rim and clean up some of Chriss’s defensive mistakes, while Chriss would use his bigger frame to guard the post and prevent Bender from absorbing too much contact in the paint. Bender would be the passer, and Chriss would be the finisher. Both will be really difficult to guard if they can improve as shooters.

That’s a lot of ifs, though, and neither is anywhere close to a finished product. There has never been a more difficult time in NBA history to foster the development of a raw, offensive-minded big man, much less two of them at the same time. Given the prevailing style of basketball in the league, it’s more challenging than ever for bigs to use their size to their advantage. The increasing emphasis on spacing the floor and forcing bigger defenders to guard in space has made learning how to play acceptable NBA-level defense at the 4 and 5 positions extremely difficult, requiring time and repetition. In the meantime, it’s almost always going to be easier for their teams to play smaller.

The Suns have been rebuilding, in one direction or another, for a while. And with a notoriously impatient owner, there’s no way to know how patient they will be with Chriss and Bender. It would be easier to be optimistic about the two if they had landed in a more stable organization, and there’s definitely a concern that they could end up cannibalizing each other’s playing time over the next few seasons. Drafting them together was an interesting gamble for a franchise that has been stuck in the lottery, stockpiling picks without establishing much of an identity for the type of team they want to become. With Chriss and Bender, they have the outlines of an identity, but it’s one that will involve an awful lot of losing over the next few seasons.