Jarvis Landry Wants First Blood

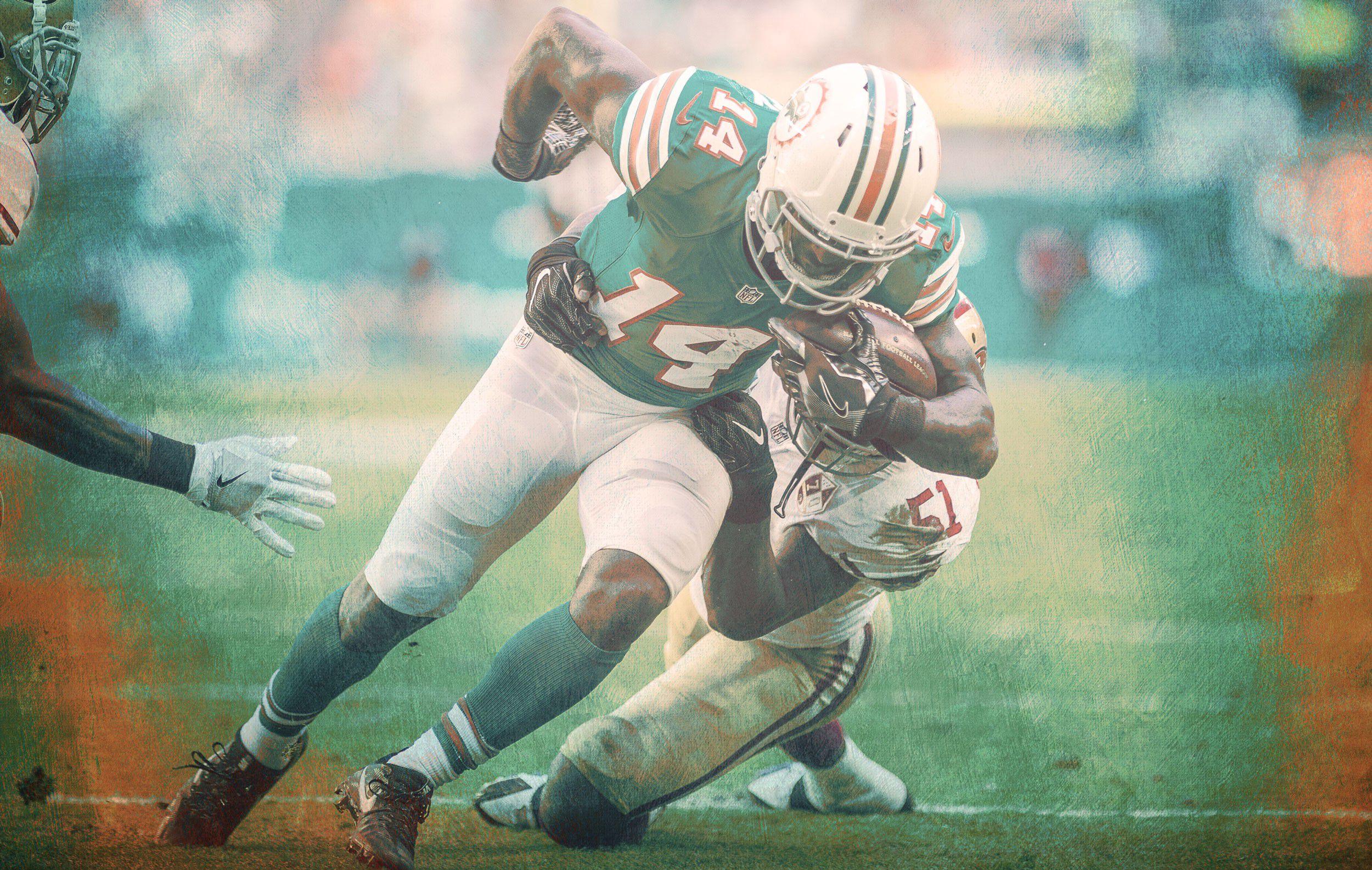

The unconventional receiver who’s sparked Miami’s playoff berth has an incomparable competitive spirit — and a cinematic desire to throttle his defendersMiami Dolphins receiver Jarvis Landry becomes a different person when he takes the field. For plenty of football players, that would be a meaningless cliché, but for Landry, it’s a specific reality: When he wakes on game days, he’s John, a former Vietnam commando; when the clock starts ticking down, though, he morphs into a fiery, bandanna-clad warrior hunting for justice and consumed by eternal battle. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the premise of the Rambo movies. Some players wear a headband to soak up sweat, but not Landry.

"For me, the bandanna, it reminds me of [Rambo: First Blood] Part II," says Landry, an aficionado of the series. "He was so in love with the war, so in love with the fight that he didn’t want to come home. Being home felt weird for him. Fighting — and for me, competing — was what he was born and bred to do. As soon as I put the headband on, I feel the same way."

In addition to boasting an active imagination, the third-year player out of LSU also possesses skills that make him perfectly equipped for this NFL era. He’s crossed the 1,000-yard receiving mark in consecutive seasons, keying the Dolphins’ revival and current playoff berth even though he lacks the size (he’s 5-foot-11) and speed (he clocked a 4.77 in the 40-yard dash) commonly associated with elite pro receivers.

In today’s high-offense, high-completion-percentage era, quarterbacks rely more on shorter passes and using the middle of the field. Landry facilitates that approach, primarily playing out of the slot, where he routinely turns short throws into big gains. This season he averaged 6.6 yards after the catch, second most among receivers with at least 60 receptions, and amassed 1,136 receiving yards on 94 receptions even though quarterbacks Ryan Tannehill and Matt Moore threw the ball just 6.4 yards on average when targeting him. This season, 37 wide receivers topped 850 receiving yards; all of them caught passes deeper down the field than Landry on average, but only nine recorded more total yardage. Among receivers with at least 30 catches, 103 NFL players caught the ball farther down the field on average than Landry this year — they just got tackled before he did. "What he specializes in is taking short gains and making them big gains," says Miami’s receivers coach, Shawn Jefferson.

That ability alone would separate Landry from the bulk of his fellow receivers. Paired with a particular brand of confidence that would shame even Ric Flair, though, it makes him the NFL’s Rambo. He likes his wars, but he’s still looking for the opposing soldier capable of slowing him.

"I have not found one yet and probably never will find one in my career," Landry says when asked whether any defensive back can stop him.

Why? "God hasn’t made one. He can’t and he won’t."

There must be someone, right? Seattle’s Richard Sherman?

"One-on-one? No."

Arizona’s Patrick Peterson?

"No."

New England’s Malcolm Butler?

"No."

Kansas City’s Marcus Peters?

"No."

He volunteers a name:

"Deion Sanders? No."

Why?

"This is simple: My will won’t allow it to happen."

Landry’s practice habits are so ferocious that Miami tight end Dion Sims says, "I’ve never seen anything like it." One ambition propels that fire and physicality: "As soon as you turn the game on you’ll know who 14 is," Landry says, referencing his jersey number, "and if you don’t, by the time I’m done you’re going to say, ‘Who is 14?’ And you’re going to Google search ‘14 and Miami Dolphins,’ and you know what’s going to pop up?

"Me. With a big smile."

Jefferson, Miami’s receivers coach, spends a lot of his free time watching nature documentaries on National Geographic Channel. His favorite thing is watching lions roam the Serengeti, and over the past few months, he’s noticed some similarities between what he sees on his TV and what he sees on the football field every day.

"The lion senses the threat right away, and he doesn’t wait for the other lion to come to him; he runs to the battle," Jefferson explains. "That’s Jarvis. He hunts. He’s not saying, ‘Let’s wait and see.’ He runs toward it and he destroys all energy and enthusiasm the defender has about covering him or blocking him by running to the fight first."

Landry admits that this may strike some as "pee-wee-football-ish," but says he doesn’t care: His philosophy is to hit his opponents before they hit him.

"I feed off of embarrassing my defender," Landry says, and in his brief time in the league he’s offered no shortage of proof:

Landry plays with a certain type of violence. Jefferson says that when he watches film, especially of plays featuring Miami’s running backs, he notices something unusual: "I’m seeing safeties who aren’t looking at Jay Ajayi," he says, referring to the Dolphins’ star runner. "They are looking for Jarvis. They are saying ‘Where is he?’ The entire defense is just thinking, ‘What is this guy going to do?’"

Jefferson points to Miami’s recent game against the Bills, who in the days leading up to the Week 16 contest had called a Landry crackback block in the teams’ earlier meeting dirty. Jefferson didn’t just identify an opponent keying in on an impact player; he identified their obsession. "If they had been [focusing on themselves], maybe they would have had 11 guys on the field," Jefferson says, mocking the since-fired Rex Ryan’s now-infamous flub of fielding 10 guys during the 57-yard Ajayi run that led to the Dolphins’ overtime win.

Disorienting opponents is all part of the plan. Because Landry operates in tight windows on the field, with most of his targets thrown near the line of scrimmage, every inch counts. Hitting the crap out of defensive backs often causes them to give him a little more space in his routes, which can be the difference between getting tackled immediately and getting yards after the catch.

Taking the battle to the defender isn’t new for Landry. Dwain Jenkins, Landry’s offensive coordinator at Louisiana’s Lutcher High School, says that when Landry, a five-star prospect, faced touted defensive backs like Dutchtown High’s Eric Reid and Landon Collins, for instance, he would purposely run toward them, especially when blocking, to test himself.

Landry has continued to employ that philosophy, through his LSU years and into the pros. "It comes back to this: If that’s your biggest, strongest, fastest guy, I may be none of those things," Landry says. "But I do know we’re about to find out what’s going to happen. It makes people — I don’t want to say people fear me, but it can get ugly."

Jenkins, now Lutcher’s head coach, says that Landry’s open-field blocks were so legendary among locals that a decade after his high school career began, "a generation of kids" who used to watch Landry from the stands now pride themselves on run blocking from the receiver position. Landry is famous in the NFL for his one-handed catches, his competitiveness, and his big plays, "but his legacy is in the blocking game," Jenkins says.

Landry craves contact in a way that is not only rare for receivers, but is, in fact, more in line with the position group he matches up against: "There aren’t receivers who have that mentality," says Dolphins safety Bacarri Rambo, a former Georgia Bulldog who played against Landry in college. "It’s a defensive back mentality." Dolphins head coach Adam Gase also sees similarities between his star offensive player and most teams’ feared defenders: "In the same way if you have a hard-hitting safety or linebacker, defenses are aware of where Jarvis Landry is," Gase says.

That’s the John Rambo in him. Off the field, Landry is laid-back, going longboarding through Fort Lauderdale alongside Dolphins tackle Ja’Wuan James. (Landry keeps a longboard at his locker with his own image painted on it.) On the field, he longboards through opponents, but that aggressiveness can come at a price.

Gerard Landry, Jarvis’s older brother and football mentor, who played receiver for Southern University, says with a laugh that he’s told Jarvis to ease off on the big open-field hits, which can lead to expensive fines. Landry’s crackback hit against the Bills in Week 7, for example, cost him more than $24,000.

So far, though, the league’s fines and his brother’s pleas have not deterred Landry: "I’ll say, ‘We gotta calm it down, we got a fine,’" Gerard says. "He just says, ‘This is how I play and this is how I want to play.’"

Landry is often pissed off. He finds chips on his shoulder the way most people find socks in their laundry. "I always think: ‘This guy in this game was the bigger name, they said this guy was better,’" Landry says. Gerard thinks the biggest motivator for his brother’s early NFL career came during the 2014 draft.

Landry’s family rented a large room at the Renaissance Hotel in Baton Rouge for friends and family to watch the draft. Landry felt stung that he wasn’t invited to attend the draft in person, and the perceived slights only grew as a string of other receivers came off the board. As he fell out of the first round and into the late second, the conversation in the hotel shifted as well: "We all started saying, ‘Is anyone watching the tape, or are you guys going off of 40-yard dashes?’" Gerard says.

Landry amassed 1,193 yards and 10 touchdowns in 2013, his junior year at LSU. But a poor combine performance hurt his draft stock, as he failed to rank in the top 10 in any category. His 4.77-second 40-yard dash would have been considered slow for a receiver of any size, but was especially damaging for a 5-foot-11 player who would typically be expected to use his speed to overcome his height disadvantage. Landry wound up being the 12th receiver picked, 63rd overall.

Landry’s friends and family scoffed. Gerard in particular knew that Jarvis was different from most football players. When he visited his younger brother during Jarvis’s freshman year of college, they sat down on a couch in Jarvis’s apartment and Gerard tried to find SportsCenter on TV. Jarvis looked stunned. "I don’t have cable," his brother recalls him saying. "I just watch film all day." Gerard remembers how Jarvis would break into the LSU facilities after midnight to practice on the Jugs football passing machine a few times a week, typically using a wooden ruler or "another sharp object" to pry the first door in the back of the building, known to be the easiest to open. Many of these relentless workouts were with Odell Beckham Jr., Jarvis’s close friend and LSU teammate, and now the star of the New York Giants.

When Jarvis declared for the draft, Gerard picked up his brother’s stuff from his Baton Rouge apartment. He found tablets containing pages and pages of notes: specifics about SEC defensive backs (which players had a high backpedal, for instance) and, more importantly, "[written] notes where he was talking to himself, showing his confidence," Gerard says. "It made me think of Muhammad Ali. That’s the kind of confidence he has."

A similar conversation to the one Landry’s family had about his measurables occurred in at least one other room on the second night of the draft. A then-Broncos assistant coach, Bo Hardegree, had been an assistant at LSU during Landry’s tenure and secured a practice tape cut-up of all his great plays. After watching this, Tyke Tolbert, Denver’s wide receivers coach, made an impassioned case for drafting Landry. It didn’t matter what Landry’s measurables were, Tolbert told the room, because he was such a competitor. At least one coach in the room listened intently: Gase, then the Broncos offensive coordinator. Seven picks before the Dolphins took Landry, the Broncos instead drafted Indiana’s Cody Latimer, who was 3 inches taller and 0.3 seconds faster than the LSU product. This year, Latimer set a career high for single-season yardage, totaling 76 yards in 12 games. He has one career touchdown. Landry had 76 yards and a touchdown against New England in Week 17.

"Everyone [in the NFL] hung on the measurables," says Gase, who’s in his first season as Dolphins head coach. "These guys in [the Dolphins front office] did a great job."

While Gase had to wait a couple of seasons to coach Landry, the competitive spirit that first stood out to him is what keys Landry’s current role in the Dolphins offense, which has improved from 27th in the NFL in points per game to 17th during this 10–6, wild-card season. Landry is the team’s "spark plug," says Gase. "The second play of the game against Pittsburgh, the game that turned our season around — a [second-and-20] and he’s taking a short pass and going for a first down," Gase says. "He’s continually taking it higher and higher. When guys hit him and he doesn’t go down, that says something."

Landry, of course, isn’t content. While he embraces his role as a short-catch specialist, he thinks he could be a bigger threat in the offense by running a wider variety of routes. "It gives the defender more to think about if it’s, ‘I gotta cover the fade, the short out, the quick out, the post,’ instead of, ‘I’ve got to cover the slant and out,’" Landry says.

Landry has more say with his coaches than most NFL receivers. Gase, a coach of the year candidate, allows his receivers to speak up if they feel they aren’t getting the ball enough. "I say, ‘Don’t wait to tell me if things aren’t going as smoothly as we planned during the week; if you don’t feel like you’ve gotten in a rhythm, I don’t want to wait to hear it in the third quarter,’" Gase says. Jefferson jokes that while Landry has the green light to say such things, he typically doesn’t have to, since coaches can tell when he’s miffed based on his sideline demeanor.

Regardless of his demeanor in a given moment, Landry remains the smartest player Jefferson says he’s ever coached. "You have to be, to be able to take a 2-yard pass and turn it into 70 yards," Jefferson says. That big-play ability stems in part from the big hits, which Jefferson says play a huge role in how defenders play Landry, but it also comes from his almost supernatural vision after he catches a pass.

"I don’t even know how to explain it," Landry says when trying to describe how he understands the nuances of defensive back play. "It might sound crazy, but a lot of times, I see shit before it happens. If I take an angle flat enough left, the safety will try to cut me off so I will cut back inside. I try to use that against guys." Landry’s vision extends to various other looks. When teams play him man-to-man, especially with one safety, making it easy to cut up field, for example, he gets to do this:

The vision, Jefferson says, is God given, but all of Landry’s skills are aided by his legendary practice habits, which, as fellow Dolphins receiver Leonte Carroo puts it, include some of the "craziest things" he’s seen on a football field. Jefferson says that he’s never seen anyone practice like Landry does, noting that when Landry doesn’t like what he does with a given rep, he’ll skip the line and immediately go again. Carroo says he once saw Landry win 50 straight one-on-one battles in practice. (When asked if this happened, Landry responds, "Probably.") Safety Michael Thomas says that Landry uses practice not for incremental improvement, but to "test his limits."

Testing limits has been a common theme in Landry’s life. Jenkins recalls that when Landry was in high school, he’d multitask while practicing fielding punts, having other people throw passes at him while he waited for the punt to arrive. But he didn’t stop adding wrinkles there: While waiting for the punt, he’d try to limit himself to catching the passes between his legs or by "stabbing" the ball, catching it with his palms down. When he got a well-thrown ball during a more routine team drill, he’d add a degree of difficulty to the catch by sticking out just one arm and keeping the other one by his side. Jenkins credits those early self-enforced drills with fueling Landry’s ability to catch passes in the NFL even when one of his arms is clamped. "Our rule was, ‘Use two hands while you’re learning,’ but Jarvis was never learning," Jenkins says. "It’s so funny, I get texts from people after he makes these ridiculous catches, and I don’t think it’s shocking — we saw him do it every day."

The confidence that sparks those one-handed grabs and comments about God not yet making a defensive back who can cover him is fueling something else: Landry has spent time working on a rap mixtape, and says he doesn’t want anyone but him rapping on it. He calls his rap style "storytelling and truth" and he doesn’t need help telling that truth.

"I feel like some of the more prestigious artists, like J. Cole or Drake in his prime, didn’t use features," Landry says. Landry likes Drake, but true to form, he still has to take a shot: "I’m not saying he’s not in his prime, but he’s kind of dipping into everything. When he first started out he was just spitting bars."

His abundance of confidence bites Landry in one place, Gerard says: He launches too many 3s when playing pickup hoops. On the football field, though, that attitude remains Landry’s biggest asset. "The field is his sanctuary and he’s the god," Jefferson says. "It’s the Colosseum and he’s the Roman gladiator. His hits are like Paul Revere: He lets everyone know what’s coming."

Landry’s consecutive 1,000-yard seasons haven’t dulled his edge, nor has Miami’s playoff berth. He still watches all of the Rambo movies to maintain his spark. His bandanna has become so famed that fans now drop them from the tunnel; he used to go with Rambo’s standard black or try to match his headband with the Dolphins’ uniform, but now he loves taking whatever the fans want to give him, color coordination be damned.

While the bandannas bring Landry joy, those around him marvel at his ability to constantly find new fodder for getting angry and working harder. In his locker, Landry keeps a large, black-and-red piece of paper that reads "97?" — the number of guys ahead of him on the top-100-players ranking that the NFL Network released over the summer.

He doesn’t want to say where he thinks he should rank now. "But until I’m number one," Landry adds, "I’m not going to stop."