Welcome to The Lineup! This is a weekly column that will examine — you guessed it — nine topics from the world of baseball in numbered order.

1. We must do something about the bees.

In the eternal struggle between baseball and football for the souls of young American athletes, baseball is often seen as the safer option. Certainly, catastrophic neurological injuries are less common in baseball than in football, but baseball players appear to be under constant siege by bees.

Mike Trout thinks this is funny, but I found this clip by searching “MLB Bees” on YouTube, and I had to scroll past 12 videos to get to the one I wanted. Along the way I could’ve stopped to watch “Bees Invade Dodger Stadium!” or “Heyward escapes bees, then hits home run” or this horrifying video of bees swarming the camera behind home plate.

Of course, the Angels’ biggest problem regarding stinging insects is how many of their players really ought to be playing for the Triple-A Salt Lake Bees of the Pacific Coast League. But we can’t ignore this. Bees are a stinging menace, single-minded purveyors of acute but momentary discomfort that demand a far more serious response than the same Arrested Development reference followed by the same Wicker Man reference every time they visit their horrors on a ballpark. MLB must address this stinging menace for the safety of players and fans alike.

2. The Giants can fix their bullpen; they just need to be creative.

The most remarkable part of the Giants’ postseason success since 2010 has been not the quality of their bullpen but the stability of their bullpen. Three different members of the Giants’ relief corps — Santiago Casilla, Sergio Romo, and Javier López — have been with the team since 2010. That’s a remarkable amount of consistency for a major league bullpen.

This year, though, some of those old parts are wearing down. Casilla, who’s closed on and off since 2012, has posted an 8.44 ERA with three blown saves in September. As a whole, the Giants’ bullpen has the second-worst WPA in baseball over the past 30 days. Things have gotten so bad that 41-year-old Joe Nathan is getting innings back there. Even if the Giants could sneak a good reliever through waivers, it’s too late for him to be eligible for the postseason. On Monday night, the Giants’ bullpen blew its league-leading 29th save, dropping San Francisco five games out of first place in the NL West and into a three-way tie with the Cardinals and Mets in the wild-card standings. They’re out of wiggle room, but they do have options.

Option 1: Conquer the Baltimore Orioles.

I don’t mean “somehow contort the schedule to set up a series with Baltimore and then beat them.” I mean, “jump in a tank, invade Baltimore, and take Zach Britton and Brad Brach hostage.” It’s a tale as old as recorded history — you have something I want, and I’m stronger than you, so I’m going to take it. And while it might take a while to get an armored column across the country, there are advantages to choosing the Orioles as a target — not only do they have two elite relievers, their weaknesses in starting pitching and team speed make them a candidate for conquest. Also, we already know that Britton and Brach look good in orange and black.

Option 2: Poison the Los Angeles Dodgers.

It’s a drastic step, but if the Giants want to avoid a wild-card game, they need to make up five games in less than two weeks. That calls for drastic action.

The good news is that accidental-on-purpose food poisoning is a time-honored tradition in both the NBA and European soccer. The Giants’ season can’t go down the crapper if the Dodgers are on it.

Option 3: Enlist film editing and CGI magic.

How can the Giants make bad pitchers into great pitchers? They could turn to Hollywood, where they do it all the time. Pitch star Kylie Bunbury can’t throw an 88 mph fastball and a killer screwball in real life, but thanks to the magical CGI ball, her character can. How many times in Bull Durham do you actually see Tim Robbins’s entire windup, from the set to the ball crossing home plate for a strike? But by the magic of editing, he turns into Dwight Gooden. Surely Silicon Valley’s favorite team could come up with some technological wizardry.

Option 4: Replace the bullpen with Madison Bumgarner.

It worked in 2014, and unlike the thing with the food poisoning, nobody has to get sick.

3. What does Prellerghazi say about labor rights?

When MLB took the unprecedented step of suspending Padres GM A.J. Preller for lying about players’ medicals, most of the focus was on how it affected the various teams involved. How much would Preller’s absence hurt the Padres in the short term? Did the Red Sox give up a better prospect for Drew Pomeranz than they might have if they’d known his full medical history? Will leaguewide distrust of Preller handicap the Padres in their future dealings with other teams and agents?

Certainly all of those questions are worth serious consideration, and as someone who enjoys big league front-office Kremlinology and the high-stakes game theory of trade negotiations, I’m here for that discussion.

But those discussions, and indeed the condemnation of Preller’s actions in the first place, are based on an assumption that the baseball world just swallowed whole without thinking about it: Management ought to have their employees’ medical records, and disseminate those records truthfully.

Baseball isn’t like a normal job, not only because of the massive public interest in it, or the massive amounts of money around it, but because unlike most white-collar jobs, the industry itself is predicated on the physical abilities of its labor force. For instance, I have tentacles instead of legs and live in a 10,000-gallon saltwater tank, but nobody at The Ringer knew that until now because it wasn’t relevant to my ability to do my job. That wouldn’t be the case if I were a professional baseball player.

So, professional athletes enjoy less privacy than ordinary employees out of necessity, and provisions for disclosure of medical information have been negotiated into the CBA, in Article XIII(G), which means — if nothing else — that the players as a group are on some level OK with sacrificing that right to privacy.

But the scope of health data is changing. Baseball has become quantified and scouted to the point where the untapped market inefficiencies are no longer in OBP or defensive shifts. Teams like the Mariners are monitoring everything about their players’ bodies with a device called a Readiband, which, as Rian Watt put it in Vice Sports, “watches you while you sleep.” Travis Sawchik wrote earlier this year about the Pirates’ player-tracking program, which includes a questionnaire about each participating player’s mental state that’s fed to manager Clint Hurdle before every game.

Things like diet and sleep absolutely affect on-field performance, but “How many hours did you sleep last night?” digs into players’ private lives in a way that “Is your UCL torn?” doesn’t. The Mariners’ program is described as “voluntary,” as is the Pirates’ program, but how voluntary is a program like this for a rookie trying to break in or a bench player on the fringes of the 25-man roster? Those guys stand to lose a great deal if they’re not seen as team players.

Baseball might not be like a normal job, but it’s still a job, and it’s odd that teams pass employee medical data around the league, from which point it frequently gets leaked to the media and repeated to the public, and we’re all just sort of OK with this. And if injury data is fair game, how long until trade discussions include details on which players are getting divorced, or who’s having financial trouble, or whose parents are sick — all of which could weigh on a player’s mind, and all of which are private issues that an employer in any other field wouldn’t dream of soliciting information about. That is, until companies in the real world started following baseball’s example in how they evaluate their employees.

In the early days of the public war of sabermetrics, opponents of empirically driven baseball analysis were fond of reminding us statheads that players are people, more than fungible figures on a spreadsheet that can be boiled down to their essence in numbers. It turns out they were right — if you treat players like numbers, you might forget to treat them with human dignity.

4. Pitch isn’t the best show on TV, and it shouldn’t have to be.

Fox’s new baseball drama, Pitch, debuts on Thursday night, and having seen the pilot already, I’m happy to tell you that I liked it a great deal. Thanks to the involvement of Fox Sports and Major League Baseball, the baseball looks real, and the lead actors are delightful.

Pitch is the first network drama about sports since Friday Night Lights went off the air, and the lack of successful sports dramas make it a bit of a risk. Not only is there some unwritten rule out there mandating that 90 percent of network dramas be about cops, lawyers, or doctors, but it’s also expensive to shoot convincing sports sequences. Plus, it’s difficult to make the grind of a season compelling week after week — a problem that Friday Night Lights avoided either by making every game come down to a last-second Hail Mary or avoiding football altogether and focusing on the daily struggle of being Matt Saracen in a world … fuck, I’m crying again.

We’ve had some pretty good sports movies in the past 10 to 15 years — the original Friday Night Lights, Goon, Everybody Wants Some!!, Miracle — and I can’t remember any of them generating as much discussion as Pitch has about whether the sports scenes will look realistic. They do, except for two small things: (1) Once you notice the baseball is CGI, you’ll never be able to stop noticing it, and (2) the reporters covering the Padres are far better dressed than any sportswriters I’m aware of.

They pay close attention to detail on Pitch, but most of the time, we don’t even ask these questions about new sports movies or TV shows, let alone cop dramas. Part of the issue is that we live in the kind of society where Neil deGrasse Tyson nitpicks the physics of Gravity, but part of it, I believe, comes from the societal norms that drive content like this.

In short, the idea that “the hard-core baseball fan” and “women” are two different constituencies with little or no overlap remains pervasive — even if it’s obviously not true.

There are still people who think of sports as a refuge from women, and because hanging a He-Man Woman Haters’ Club sign on your door is impolite in this day and age, the obvious shibboleth to use to undercut a portrayal of a woman playing big league baseball is authenticity. For some, Ginny Baker’s presence at the center of the story is enough to undermine the legitimacy of the whole show unless every stitch on the uniform and every pixel on the ersatz Fox Sports 1 graphics package is exactly where it would be in real life.

Perhaps the most authentic thing about the show is that, because it’s about a woman breaking barriers in sports, Pitch is going to need to be twice as good to get half as far.

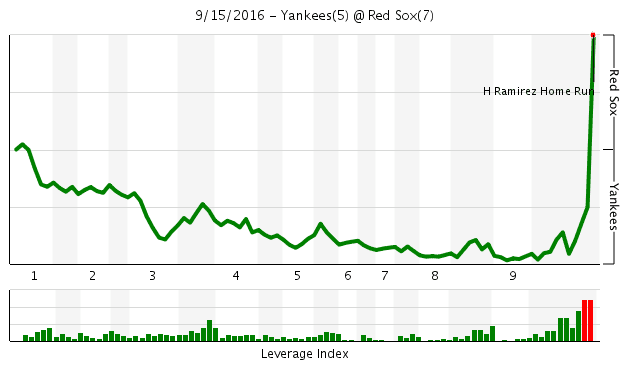

5. WPA Graph of the Week goes to the Yankees and Red Sox.

I’m not sure this chart does this game justice. When Dellin Betances came in, the Yankees were up 5–2 with one out in the ninth inning, and whatever your WPA is against a normal pitcher, you’ve got to cut it in half against Betances — especially when he has to get only two outs.

Nevertheless, the Red Sox scored five runs in the bottom of the ninth, overcoming 50-to-1 odds to win and making up 75 points of win probability on Hanley Ramírez’s walk-off three-run homer alone. Ramírez is slugging .806 in September. Once the playoffs start, Boston’s lineup is going to be an absolute chore for opposing pitchers.

6. The High Desert Mavericks go out on top.

On Saturday night, the High Desert Mavericks, the Rangers’ High-A affiliate, pulled off a rare double: They won the California League title, then closed their doors for good. The Mavericks and Bakersfield Blaze, a Seattle Mariners affiliate, will both be contracted, shrinking the California League from 10 teams to eight.

Organizational affiliations for minor league teams are fluid, and every year around this time, the deck gets shuffled a little. Next year, the Mariners will take over the Modesto Nuts from the Colorado Rockies, who will take over the Lancaster JetHawks from the Astros; the Rangers and Astros will move their High-A operations to new franchises in the Carolina League, in Kinston and Fayetteville, North Carolina, respectively.

Big league clubs swap minor league affiliates for many reasons, but the California League has become undesirable not for reasons of economic viability or geographic convenience, but because its high-altitude hitters’ parks make it a tough place to develop pitchers. We know what altitude does to a batted ball in Denver, and it’s no different in the minor leagues. High Desert always reminded me of Levon Helm’s narration of The Right Stuff, and apparently in conditions that high, dry, and hot, the batted baseball itself resembles a rocket plane.

With cities like Fayetteville willing to pay for a new ballpark back east, there’s no reason for the Astros to keep subjecting their pitching prospects to conditions like that, but the California League’s game of musical chairs left two cities without a team to fill their parks. It’s a concession to the developmental needs of big league clubs, and it leaves cities — even Bakersfield, whose population of more than 370,000 makes it bigger than Anaheim, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, St. Petersburg, or Cincinnati — without professional baseball.

If you have access to live major league baseball, as tens of millions of Americans do, it’s easy to think of affiliated minor league teams as nothing more than a holding pen for prospects, until you read something like Jen Mac Ramos’s Hardball Times story on the Blaze’s last game in Bakersfield. Those farm teams often develop dedicated followings in their own right, and when they fold, they leave behind gaps in their old communities. The slow abandonment of the California League might make good baseball sense, but it still sucks.

7. The A’s and Rays will play a scheduled doubleheader next year.

I don’t care if this doubleheader’s going to force people to watch 18 straight innings between two bad teams in the Trop; this is great. Scheduled doubleheaders used to be commonplace when it still took the train a day to get from Washington to St. Louis, but in modern times, when transcontinental flight is routine and a single day’s take at the gate is worth millions of dollars, doubleheaders are mostly reserved for makeup games.

We’re not close to this happening, but a return to weekend doubleheaders would allow MLB to play 162 games without running into unplayably cold and snowy conditions at both ends of the schedule. It would also allow fans to park themselves in a seat at a ballpark and just mainline baseball for 18 innings, or get up and wander the stadium without the pressure of knowing that you’ve paid $40 for two or three hours of entertainment and every pitch you miss is a big deal. It’d be great if this experiment worked and doubleheaders became even somewhat more common.

8. The Reds can’t stop getting dingered on.

Cincinnati is the closest major league city to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, which was once home to the 17th Bombardment Wing of the U.S. Air Force. The proximity is appropriate because Reds pitchers have been giving up bombs at a rate that would make Curtis LeMay blanch.

Big league pitchers are giving up 1.17 home runs per team per game, which would tie the all-time record, and the Reds — a last-place team in a hitters’ park — are doing their part. Cincinnati pitchers have allowed 242 home runs, breaking a record previously held by the 1996 Tigers, a team with a 6.38 team ERA.

9. Please, BBWAA, don’t screw the Trout.

Ken Rosenthal of Fox Sports wrote a column on Monday called “How will voters rob Mike Trout of the MVP this year?” Rosenthal states the problem succinctly: “Trout, 25, has been the best player in baseball for five seasons now, yet he has won only one MVP, finishing second three times. The reason to rob him this year — there’s always a reason, some new narrative — is that the Angels stink. As if that is Trout’s fault.”

It’s not often that we know who the best player in the league is to the extent where we can treat it like objective truth, but this is such a season. As recently as a month ago, I was talking myself into Josh Donaldson being on Trout’s level as a two-way player or the tidy narrative of José Altuve’s career year dragging the Astros to the playoffs, but those two have fallen off. Trout’s closest competitor in both FanGraphs and Baseball-Reference WAR right now is Mookie Betts, who’s having a great season but still trails Trout by more than a win on all three fronts. And Trout is destroying him offensively — a 170 wRC+ to 134 — so in order to even get that close you have to believe that Betts is providing significantly more defensive value as a right fielder than Trout is as a center fielder.

The point is this: Writers, this is a layup. There’s no objective MVP case for anyone else, and Trout’s numbers are so far ahead that any narrative argument against him would deny history. Somehow, with only one MVP award in the bag despite being by far the best player in baseball for half a decade, Trout’s given us Trout MVP fatigue. I only hope it doesn’t cost him more hardware down the road.

All stats current through Tuesday afternoon.