The NFL quarterback has long been the most important position in sports, and that significance has only grown as passing yardage has risen nearly 20 percent since 2005. And as the position has evolved during the modern era, there’s been just one constant: the league’s continued inability to protect its passers.

QB safety isn’t a new talking point, but after an opening week in which some of the league’s most high-profile passers were routinely savaged by defenses that received surprisingly few penalties, it’s become one of the story lines that could define this NFL season. It’s gotten so pressing so quickly that commissioner Roger Goodell had to address the matter before the season’s first Monday Night Football game in Washington, saying, “What is it we can do to try to ensure that those hits don’t occur?”

Goodell isn’t the only one asking that question; he’s also not asking all of the questions. While most fan and media outrage has focused on Carolina’s Cam Newton, whom the Broncos blasted in the helmet on four plays and slammed to the ground on more while getting flagged for roughing the passer only once on Thursday night, Newton wasn’t the only QB to get routinely rocked in Week 1.

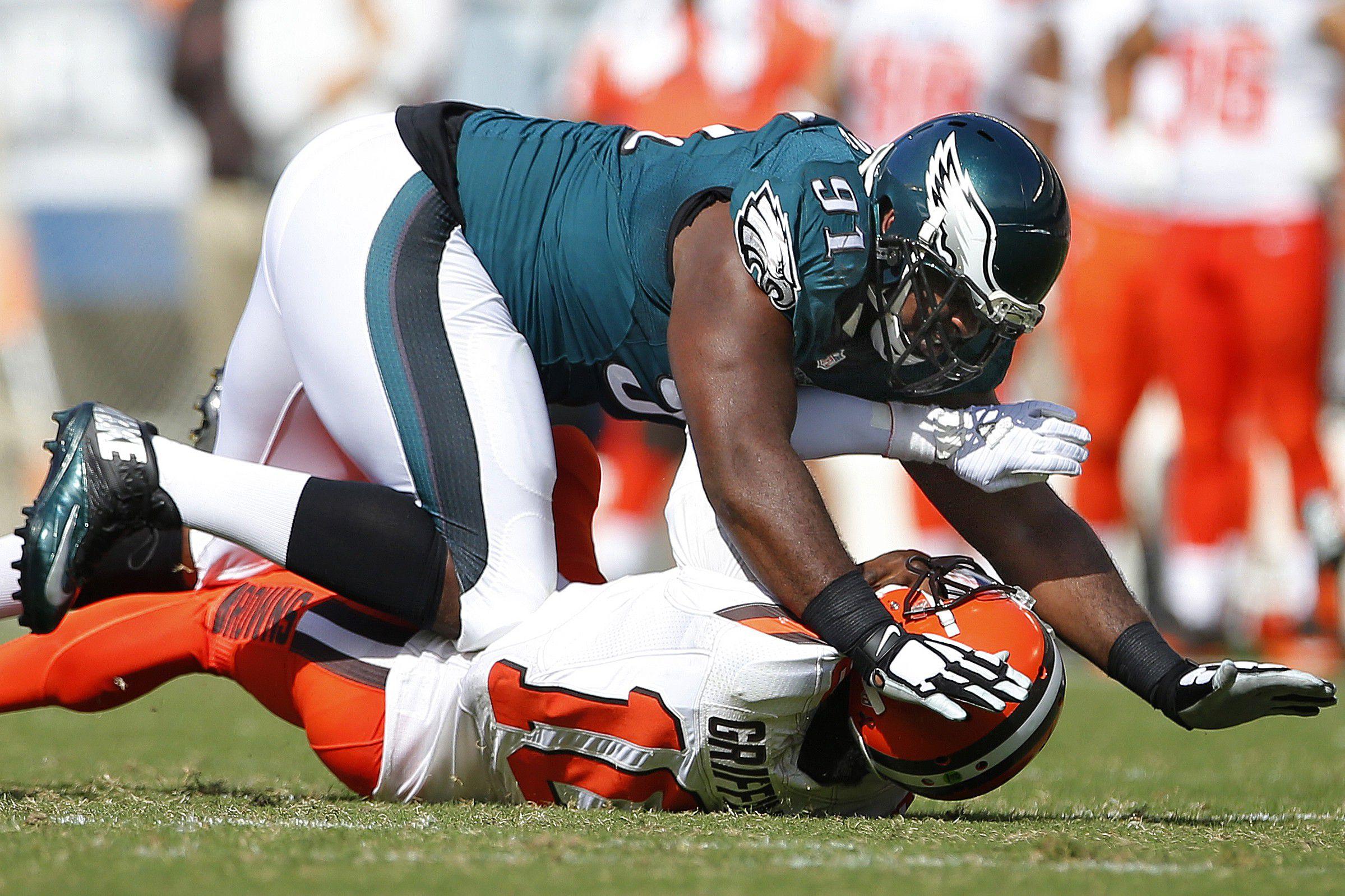

Seattle’s Russell Wilson was hit by Miami’s Jason Jones just after he released a pass (which was intercepted), prompting the announcers to say Jones should have been penalized. Wilson is also currently nursing an ankle injury sustained when Ndamukong Suh stepped on it in what appeared to be an incidental but injury-inducing play. Robert Griffin III, meanwhile, could miss the rest of the year after a brutal hit landed him on the injured reserve with a broken bone in his shoulder. (He was running outside of the pocket at the time of the hit, though, so the roughing the passer penalty is tougher to enforce.)

The league’s concussion protocol was already dominating the discussion, and now the focus will expand to include the officials’ role in legislating these quarterback hits. Five years ago, officials called 107 roughing the passer penalties; last year that figure somehow stayed steady at 104 … even though QBs threw close to 900 more passes. With the league admitting that some illegal hits are going uncalled, there’s growing concern that the NFL is not properly equipped to penalize offenders.

“It boggles my mind,” said Jim Daopoulos, who was an NFL referee for 11 years and the supervisor of officials for 12.

At the heart of the matter is the current penalty system — not just how many yards roughing the passer should cost, but also the league’s inability to make sure illegal hits in the backfield are called in the first place.

The first problem is essentially this: In a sport in which viewers everywhere are watching one position, there’s only one person in each game tasked with officially protecting the men who occupy that spot, and it’s getting harder to do so.

This starts with where NFL referees are stationed on the field. Since side judges were added in 1978, there have been seven officials per crew. Despite numerous changes in style of play and an uptick in the pace of play since, the head referee on each crew still has the same general responsibilities, which includes being the only member of the officiating team who can call penalties involving the quarterback. An NFL spokesman said that while “other officials can provide input,” the referee “is ultimately responsible for fouls on the quarterback.”

The referee lines up on the right-hand side of a play, usually about 12–15 yards deep, behind the quarterback. Current Fox rules analyst and former NFL vice president of officiating Mike Pereira said that placement is intended to, among other things, position the referee to correctly analyze whether a quarterback’s arm is going forward on a borderline pass/fumble play. The crew’s umpire is on the left side of the play, closer to the line of scrimmage, but while his physical location might make him well-suited to call hits on the QB, he’s primarily tasked with focusing on penalties in the blocking action of the interior line, making a quarterback hit hard to track.

“You could say it’s a bit outdated,” Pereira said of the setup.

The ref’s placement creates massive holes in his vision once the play starts. Because the referee can’t see in front of the quarterback, no one is positioned to, for instance, make the call when a defender’s helmet moves from the quarterback’s sternum to his chin as the passer falls to the ground. And unfortunately, few other angles are better. The modern NFL play explodes quickly: Edge rushers move around the outside, defensive tackles clog the middle, and a circle of massive 300-pounders surround the quarterback almost immediately after the snap. As Pereira put it, the issue of referees having the right angle starts with “6-foot officials trying to see around huge, 6-foot-4, 6-foot-5 linemen.”

Daopoulos said that depending on how a given play develops, nearly any quarterback hit can be hidden from the ref’s view. More complex schemes mean unpredictable defensive line twists or blocking patterns, which can make it harder to predict the angle from which to best judge a quarterback hit, leaving the responsible party on the field incapable of spotting, let alone calling, what millions of people at home could clearly see.

“You have to do whatever it takes to protect the quarterback,” Daopoulos said. “But it happens so quickly now and with the angles they have, they will flat-out miss a lot of these hits. The referee loses the angle and loses seeing what happens to the quarterback.”

To help combat this limitation, Daopoulos would like to see crews expand to eight officials. He noted that in Week 2 of the past two preseasons, the league conducted experiments with crews of that size, but those trials were primarily aimed at devoting another pair of eyes to the offensive line or defensive backfield. To better officiate hits on the QB, Daopoulos said, the eighth official would need to be closer to the line of scrimmage than any other official; he’d also have to be tasked exclusively with watching the quarterback and be able to move around freely with the single purpose of monitoring him. Currently, the referee watches the running back, quarterback, and anyone else lined up in the backfield, and also keeps an eye on the offensive line.

That setup partly explains why it’s so hard to protect a quarterback like Newton, though it’s certainly not the only theory for why officials let vicious helmet-to-helmet hits go uncalled. Newton’s coach, Ron Rivera, speculated to reporters the day after Thursday’s game that, like Shaquille O’Neal, Newton is so big that referees think he can take the punishment from opponents. “There’s a little bit of prejudice to that … he goes to shoot a little layup and gets hacked and hammered and they don’t call it,” Rivera said at a Friday press conference. Pereira, meanwhile, said that running quarterbacks may be slightly less likely to get a call on certain pass plays, because the referee may brand the quarterback as a runner if he looks like he might take off. Once the quarterback becomes a runner, he’s considered the same as any other player. “If a quarterback is in a passing posture,” Pereira said, “it’s a little bit easier to make the call.”

If the league is too intractable to change where referees stand or how many officials are in each crew, it will need to find ways to deter the hits from occurring in the first place. “Maybe the question becomes: Is the 15-yard penalty enough?” Pereira said. “Is the yardage and the fine money enough to deter it? I’m not so sure.”

The quarterback position is almost absurdly valuable in today’s NFL: Teams that lose theirs often struggle to recover, as the Colts found out last season when they lost Andrew Luck and finished 8–8 after playing for the AFC title the season prior. One vicious, envelope-pushing hit can alter a season, but the league’s current penalty structure isn’t enough to deter these kinds of blows. In addition to being docked 15 yards for the flag during the game, players are fined just $18,231 for a first roughing the passer violation.

In 2013, the NCAA added an automatic ejection on top of the preexisting 15-yard penalty for targeting a defenseless player above the shoulders, and Pereira wonders if adopting a similar ejection rule would lead to fewer unsafe hits on the QB in the pros.

“If I’m an NFL rules maker, maybe I’m thinking colleges are more concerned with head or neck penalties with that automatic ejection,” Pereira said. “You could really make a powerful statement in the NFL game where you have 46 active players, not college where you have 100. A disqualification for a hit on a quarterback would be huge.”

The NFL declined to comment on possible changes to the roughing the passer penalty.

Even if the NFL isn’t willing to go as far as instituting an automatic ejection policy, it can still gain some guidance from the college game. Daopoulos, now an officiating consultant for the American Athletic Conference, has learned firsthand how valuable replay can be, and he’s baffled by the NFL’s failure to use replay to assess quarterback hits.

“You have replay as an officiating tool, use it: Don’t use it to see if the 12th man got off the field, use it as a safety tool and protect the quarterback,” said Daopoulos, who thinks any potential hit to the QB’s head should be subject to automatic review. While the automatic review structure is currently in place for any scoring play or change of possession, expanding that process would be a touchy subject in the rigid NFL, where the Competition Committee hasn’t changed the replay process despite pleas from coaches as esteemed as Bill Belichick to make anything on the field reviewable. Though the committee has never specifically discussed amending the rules for quarterback hits, its longstanding concern over too many reviews prolonging the game applies, as does its fear of the unintended consequences of extra replay.

The replay issue may get more heated as the season goes on, especially if the types of hits the Broncos levied against Newton occur in another marquee game like Thursday’s season-opening matchup. The league may fear the unintended side effects of introducing more replay or even more officials, but meanwhile, it’s allowing another severe consequence to emerge: the most famous players in the game aren’t being protected from an increased injury risk. “The shots Cam took, that kind of head-hunting, I don’t care where the referee is,” Pereira said. “You’ve got to see those.”